Datasets

GWAS data

We downloaded the publicly available GWAS summary statistics and SNP heritability estimates for traits in the UKB from Ben Neale’s laboratory (see the URL section below). We focused on traits with SNP heritability estimates exceeding 0.04.

LoF data

We used LoF burden test summary statistics from the UKB with 454,787 participants, as previously reported1. Specifically, we utilized the gene-level aggregated effect estimates from predicted LoF variants with a minor allele frequency of less than 0.01%. Data were downloaded from the GWAS Catalog67.

Perturb-seq data

We utilized the genome-wide Perturb-seq dataset in K562 reported by Replogle et al.2. In this dataset, all expressed genes (n = 9,866) were targeted by a multiplexed CRISPRi sgRNA library in K562 cells engineered to express dCas9–KRAB. Single-cell RNA sequencing was performed to read out the sgRNAs together with the transcriptome. Only cells with a single genetic perturbation were used for the analysis, amounting to a median of 166 cells per gene perturbation and 11,499 unique molecular identifiers per cell. We downloaded the raw count data that the authors uploaded to figshare (see the URLs in the Code availability section).

For additional analyses, we utilized Perturb-seq data for essential genes in K562, RPE1 (ref. 2), HepG2 and Jurkat57 cell lines. Only cells with a single genetic perturbation were used for the analysis. The number of perturbations and the number of cells per perturbation are summarized in Supplementary Table 4. We downloaded the raw count data uploaded to figshare (see the URLs in the Code availability section) or the Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE264667).

ChIP–seq data

We utilized chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP)–seq data in K562 for annotating gene programs. We downloaded 830 transcription factor ChIP–seq narrow peak files from the ENCODE project website48 (see the URL in the Code availability section). All coordinates were mapped to hg19 with LiftOver68.

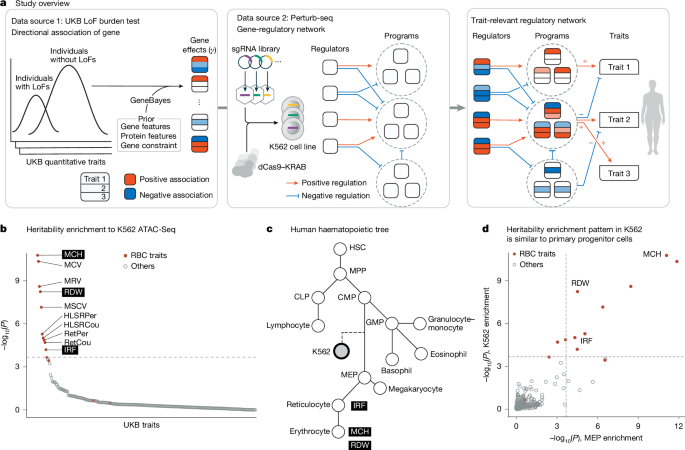

Linkage disequilibrium score regression

To identify traits whose heritability is enriched in open chromatin regions in K562, we used S-LDSC9. All GWAS data were preprocessed with the ‘munge_sumstats.py’ script provided by the developers (see the URLs in the Code availability section). Variants in the HLA region were excluded from the analysis. The assay for transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing (ATAC-seq) replicated narrow peak bed file in K562 was downloaded from ENCODE48 (GSE170378, ENCFF590CPE), and the coordinates were mapped to hg19 using LiftOver68. Furthermore, we used narrow ATAC-seq peaks from 18 haematopoietic progenitor, precursor and differentiated cell populations previously reported69.

For the additional analysis, replicated narrow peak files from ATAC-seq experiments for HepG2 and CD4+ T cells were downloaded from ENCODE48 (ENCFF439EIO and ENCFF246KRE), and the coordinates were mapped to hg19 using LiftOver68. For RPE1 (ref. 70) and Jurkat71, as narrow peak files for ATAC-seq experiments were not available, we downloaded SRA files from the US National Institutes of Health NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRR30621812 for RPE1, and SRR12368304 and SRR12368305 for Jurkat) and called the peaks. Specifically, we trimmed the adapter sequence with TrimGalore (v0.5.0)72, aligned to the hg19 reference with Bowtie2 (v2.3.4.1)73, filtered duplicates with MACS3 (v3.0.3)74 and called narrow peaks with the MACS3 (v3.0.3) hmmratac command.

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) scores were calculated for each annotation using the 1000 G Phase 3 European population (ref. 75). The heritability enrichment of each annotation for a given trait was computed by adding the annotation to the baseline LD score model (v1.1) and regressing against trait chi-squared statistics for HapMap3 SNPs. These analyses used v1.0.1 of the LDSC package (see the URL in the Code availability section).

Furthermore, we tested the genetic correlation between specific trait pairs using European LD scores with the LDSC package (v1.0.1).

Estimation of gene effect sizes with GeneBayes

Method overview

LoF burden tests are not well powered, especially for shorter or selectively constrained genes, as the likelihood of having LoF variants in these genes is low. We previously developed GeneBayes44, an empirical Bayes framework aimed at addressing a similar challenge: the precise estimation of selective constraint on genes, which can be particularly challenging for short genes. Within GeneBayes, we used gene features in a machine learning-based empirical Bayes framework to improve the accuracy of constraint estimates. Diverse gene features, such as gene expression patterns and protein structure embeddings, can enhance the accuracy of these estimates. GeneBayes is a highly adaptable framework, easily extendable to various applications, as outlined in the original article44. In this instance, we utilized it to derive more precise effect size estimates for LoF burden tests.

To minimize overfitting when applying GeneBayes to LoF burden test estimates, we first performed feature selection using the BoostRFE function (boost recursive feature elimination) from the shap-hypetune package (see the URL in the Code availability section) to fit XGBoost76 models on the sign and magnitude of \(\hat\gamma \), the estimated effect size from LoF burden test summary statistics. We used the predicted sign and magnitude as the features for GeneBayes, which we found to perform better than using the selected features directly; this may be due to differences in training dynamics between XGBoost and the gradient-boosted trees fit using GeneBayes.

Subsequently, we implemented the GeneBayes framework as previously described. Specifically, GeneBayes involves two steps: (1), learning a prior for the effect size of each gene through the utilization of gradient-boosted trees, as implemented in NGBoost77, and (2), estimating gene-level posterior estimates of the effect sizes using a Bayesian framework. In our application of GeneBayes, we parameterize the prior as follows:

$$\mathrmsign(\gamma ) \sim \mathrmBernoulli\,(p)$$

$$\mathrmmagnitude(\gamma ) \sim \mathrmGamma(\alpha ,\theta )$$

The parameter p is the probability that γ is positive or negative, and α, θ are the shape and scale parameters of the Gamma distribution, respectively. We learned the parameters of the prior using the following likelihood:

$$\hat\gamma |\gamma \sim \mathrmNormal(\gamma ,\,\rms.e.(\hat\gamma ))$$

The summary statistics \(\hat\gamma \) and \(\rms.e.(\hat\gamma )\) are the estimated effect size and its standard error from the LoF burden tests, respectively.

Gene features

We compiled the following types of gene features from several sources: selective constraint of genes (Shet)44, gene expression across cell types, protein embeddings and gene embeddings.

Shet refers to a reduction in fitness for heterozygous carriers of a LoF variant in any given gene. We utilized the Shet estimated in our previous work44. Gene expression across 79 single-cell types was downloaded from the Human Protein Atlas78 (see the URL in the Code availability section). Protein embeddings were adopted from embeddings learned by an autoencoder (ProtT5) trained on protein sequences79. Gene embeddings were derived from GeneFormer, a pretrained deep learning model for single-cell transcriptomes80. Specifically, we used the Cell×Gene Discover census (see the URL in the Code availability section), and we extracted 1,000 cells per each of the cell types—‘erythroid progenitor cell’, ‘monocyte’, ‘erythrocyte’, ‘fibroblast’, ‘T cell’, ‘neutrophil’, ‘B cell’ and ‘haematopoietic stem cell’—and computed the average embeddings of each gene for the cellular classifier using the EmbExtractor module (see the URL in the Code availability section).

Finally, we used the posterior mean of the LoF burden test effect size as a point estimate for the following analyses.

Traits

As applying GeneBayes to all UKB traits is computationally intensive, we applied this to a subset of traits including all the blood cell-associated traits, blood biomarkers and some of anthropometric traits. A list of traits included in our analyses has been provided in Supplementary Table 5.

LoF burden test in the All of Us cohort

The All of Us dataset contains whole-genome sequencing together with various laboratory measurements45. On 5 February 2025, the values for MCH were reported for 213,787 sequenced individuals after filtering (UKB data-field 30050, AoU ID 3012030). For individuals with data from multiple visits, we took the latest visit, and we excluded outliers (more than 50 or less than 0 pg). Our previous analysis suggested that relatedness and population structure have a minimal effect on burden test results58. Therefore, we performed our tests on all individuals that passed our filtering criteria. We included the top 16 genotype principal components, which are provided in the data release. In addition, we generated 20 rare variant principal components using FlashPCA2 (ref. 81) on variants sampled uniformly at random from the rare variant fraction (minor allele count (MAC) > 20, minor allele frequency (MAF) < 1%). We identified high-confidence LoF sites using the Variant Effect Predictor in Ensembl82 with the LOFTEE plugin83 and restricted our analyses to variants with MAF < 1%.

We performed burden tests using REGENIE84, largely following the procedure previously described58, which is based on ref. 1. We used HapMap SNPs85 extracted from the ACAF call set (a set of variants provided by All of Us filtered on MAC and MAF) to perform the whole-genome regression in the first step of REGENIE. We included age, sex, age-by-sex, age squared, 16 genotyping principal components and 20 rare variant principal components as covariates in both the first and the second steps. We used the rank-inverse-normal transform on the phenotypes in both steps. The burden mask aggregated all LoF sites with MAC > 5 and MAF < 1% into a single burden genotype for each gene. We added Gaussian noise to summary statistics generated from fewer than 20 individuals to remain in compliance with the All of Us Data User Code of Conduct. The noise was added to the effect size such that all burden tests with fewer than 20 individuals had the same standard error.

Pathway enrichment analysis of GWAS and LoF top hits

Clumping of GWAS top variants

To identify independently associated GWAS variants, we used PLINK (v1.90b5.3)86 with the –clump flag, a P value threshold of 5 × 10−8, a linkage disequilibrium threshold of r2 = 0.01 and a physical distance threshold of 10 Mb. In addition, we merged SNPs located within 100 kb of each other and selected the SNP with the minimum P value across all merged lead SNPs to avoid the false inclusion of genes that have neighbour genes with extremely large effects. This resulted in 634 independent variants associated with MCH. For each independent variant, we annotated the nearest protein-coding gene. To accomplish this, we used the bedtools (v2.30.0)87 closest module to identify genes that overlap with the variant or have their transcription start site or transcription end site closest to the variant. Furthermore, we excluded genes in the HLA region due to extensive linkage disequilibrium. Finally, we obtained a list of 543 genes possibly associated with MCH GWAS signals.

Pathway enrichment analysis

We aimed to compare the pathways enriched in GWAS and LoF top hits for MCH. As pathways, we utilized all ontology terms in Gene Ontology88 with a minimum of 20 genes and a maximum of 2,000 genes, as well as MsigDB hallmark genesets89 that include the haem synthesis pathway. We utilized enrichGO and enricher functions in clusterProfiler90 package in R for the analysis.

Among the enriched pathways, genes in the ‘positive regulation of macromolecule biosynthetic process’ pathway overlap significantly with those in the ‘autophagy’ pathway (P = 2 × 10−8), and thus its enrichment may reflect the relevance of autophagy pathway.

Enrichment analysis of GWAS and LoF top hits to HBA1 regulators

For the evaluation of the enrichment of GWAS top hits related to HBA1 regulators (Fig. 3b), we used the list of 543 closest genes to the independent GWAS hits defined above. We ranked the genes based on the P values of their regulatory effects on HBA1 expression. For each of the different thresholds for HBA1 regulators, we evaluated the enrichment using a two-sided Fisher’s exact test, using all the genes perturbed in the Perturb-seq as a background. Specifically, the columns of the 2 × 2 table for the test correspond to whether the genes are HBA1 regulators at each threshold, whereas the rows correspond to whether the genes are GWAS top hits.

In addition, for comparison, we evaluated the enrichment of 90 significant genes in the LoF burden test (FDR < 0.1) and the genes closest to the top 90 independent GWAS hits.

Estimation of gene-regulatory effects from Perturb-seq

We aimed to estimate gene-to-gene regulatory effects from Perturb-seq. We assessed the total effects of gene knockdown on gene expression by comparing perturbed and non-perturbed cells. After filtering out cells with fewer than 500 genes expressed and genes expressed in fewer than 500 cells, we compared the cells with perturbation of every gene versus the cells with non-targeting control gRNAs. Log-normalized counts of cells were used as input to the limma-trend pipeline91, while accounting for gel bead-in-emulsion (GEM) group (batch effect), number of genes expressed and the percentage of mitochondrial gene expression as covariates. We utilized the log2 fold change (logFC) of gene expression in perturbed cells compared with non-targeting cells as a point estimate of the perturbation effect on gene expression \((\beta _x\to y)\).

Defining gene programs and the regulatory effects of genes

Identification of gene programs with cNMF

From a single-cell gene expression matrix, we identified the co-regulated set of genes. Intuitively, such a set of genes can correspond to genes that determine cellular identity or specific cellular processes, which we call programs. To identify gene programs and their activity in each cell, we applied the cNMF47 method to the single-cell gene expression matrix from Perturb-seq.

Matrix factorization models the gene expression data matrix as the product of two lower rank matrices, one specifying the proportions in which the programs are combined for each cell, and a second encoding the relative contribution of each gene to each program47 (Fig. 4a). We refer to the first matrix as a ‘usage’ matrix47. In cNMF, the usage matrix is normalized so that the usage values for each cell sum to 1. We used the normalized matrix as a usage of each program in each cell.

In cNMF, a meta-analysis of multiple iterations of NMF was performed to obtain a ‘consensus’ result. In cNMF, the number of programs (K) is a key model hyperparameter to tune. To determine it, we tested different values of K (30, 60, 90 and 120) and decided to proceed with K = 60 based on the error versus stability comparison (Extended Data Fig. 4a), as proposed by the authors. In addition, we used density threshold = 0.5 to filter out the outlier programs.

Annotation of programs to biological pathways

From the gene-by-program matrix produced by cNMF, we can obtain the non-negative loadings of each gene to the program. We ranked the genes based on the loadings and utilized the top-ranked genes for each program to characterize the biological pathways of the program.

Annotating the programs to specific biological processes is a multifaceted task. In this study, for each program, we considered three orthogonal lines of evidence for annotating biological pathways.

Gene Ontology enrichment of top genes

We examined the enrichment of the top 200 genes in the Gene Ontology categories and MsigDB hallmark gene sets using the enrichGO and enricher functions in the clusterProfiler90 package in R. To calculate the enrichment, we utilized genes expressed in K562 cells as a background set to avoid bias.

We tested different thresholds for determining the top genes (100, 200, 300, 400 and 500). The Gene Ontology enrichment results were generally consistent, but we observed a trend: as the number of included genes increased, more categories were enriched in at least one program, with fewer categories specifically enriched for one program (Supplementary Fig. 10).

Capturing a wide range of biological categories, as well as annotating specific categories to the programs, is important for interpretation. Thus, we chose to use the top 200 genes for the Gene Ontology enrichment analysis.

Enrichment of transcription factor-binding sites

We can expect that for some programs, the genes within the same program are coordinately regulated by specific transcription factors. Such transcription factors can be used to characterize the programs. To this end, we utilized the ChIP–seq experiments of transcription factors in K562 from the ENCODE project. To convert the information on binding sites to a gene-level regulation score, we calculated the following score for each transcription factor (i) for each protein-coding gene (j), as adopted from ref. 92:

$$S_i,j(d)=\sum _kP_i,k\times e^-x_i,j,k/d$$

where Pi,k denotes the strength of peak k for transcription factor i (quantified by −log10 q value for each peak, outputted by MACS2), xi,j,k denotes the distance from peak k to the transcription start site of gene j, and d represents the decay distance. The decay distance indicates the effective distance for the transcription factor and can vary depending on the transcription factors. Here we set the value to 1 kb, 5 kb, 10 kb, 50 kb, 100 kb, 500 kb or 1 Mb.

To determine which score was useful for the annotation of programs, we tested the correspondence of the score with differentially expressed genes (DEGs) after knockdown of the same transcription factor. Specifically, for each transcription factor, we listed positive or negative DEGs after knockdown in Perturb-seq (FDR < 0.1) and we compared the ChIP–seq score (Si,j(d)) between DEGs and non-DEGs by Mann–Whitney U-test.

As a natural consequence, we could annotate each transcription factor as an activator or inhibitor, according to the direction of effects after knockdown. We annotated a transcription factor as an activator if the downregulated DEGs after knockdown had significantly high ChIP scores (FDR < 0.05), and as an inhibitor if the upregulated DEGs after knockdown had significantly high ChIP scores (FDR < 0.05). As a result, ChIP scores for 167 transcription factors showed significant correspondence with their knockdown effects (FDR < 0.05) and were utilized for the annotation of programs. One best decay distance parameter was selected for each transcription factor based on the significance in the overlap with DEGs.

For each program, we compared the top 300 loading genes with other expressed genes in K562 with respect to the 167 ChIP scores using the Mann–Whitney U-test. This test evaluates the enrichment of binding sites of the transcription factors to each program genes. Furthermore, we compared the program activity of the transcription factor-knockdown cells with others to see whether the transcription factor had a direct effect on the activity of the program (Extended Data Fig. 4b).

Co-expression with marker genes

In addition, we manually confirmed the co-expression of marker genes for predefined cell types or pathways and the program activity of cells in the uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP)93 space. Markers for red blood cells, myeloid cells and the integrated stress response pathway were adopted from the original Perturb-seq paper2. S phase and G2/M phase marker gene sets were adopted from ref. 94. Markers for erythroid progenitors and megakaryocytes were determined from single-cell gene expression data of bone marrow haematopoietic progenitors95, where we ranked the genes in each corresponding population based on expression specificity (Z-score) compared with other populations and selected the top 50 genes. This number of genes was determined to be roughly in the same range as the number of genes in the other gene sets.

After completing these three tests for each program, we defined the curated annotation of each program as follows: initially, when the program corresponded to specific cell types, including cellular marker genes as top-loading genes, it was annotated as the cell type. For the others, we considered them as programs reflecting cellular pathways. We prioritized the most significantly enriched Gene Ontology or MsigDB pathways from the top 10 enriched pathways while avoiding ambiguous pathways for interpretation (such as the ‘RNA binding’ pathway). In cases in which multiple programs were enriched for the same category, we attempted to distinguish them by their enriched transcription factors or colocalization with marker gene expression. Finally, we curated one annotation per program while considering these factors (Supplementary Table 3).

Estimation of the regulatory effects of genes on program activity

From the cell-by-program matrix produced by cNMF, we obtained the usage of each program in each cell. To obtain the effect size of each regulator on the program usage, we standardized the program usage to mean = 0 and s.d. = 1, and we compared perturbed cells with cells with non-targeting control gRNAs with a linear regression model, while accounting for GEM group (batch effect), number of expressed genes and percentage of mitochondrial gene expression as covariates. We utilized the point estimate of the effect size of perturbation on program usage as a regulatory effect of a gene \((\beta _x\to P)\).

Comparison of program regulations with genetic associations

Definition of gene effects on traits and gene regulation

Unless specified, we utilized the posterior estimate of gene effect size on a trait with GeneBayes as the gene effect on a trait (γ). For gene-level regulatory effects, we used the logFC of gene expression in perturbed cells compared with non-targeting cells as a point estimate of the perturbation effect on gene expression, as described above \((\beta _x\to y)\). For program-level regulatory effects, we utilized the effect size of perturbation on program usage as a regulatory effect of a gene, as described above \((\beta _x\to P)\).

Correlation of gene regulatory effects with genetic associations

We started from a simple model in which the effect size of a peripheral gene x was determined by its regulatory effects on a limited set of core genes. In cases in which there was a single or a limited number of core genes y, the regulatory effect size of the peripheral gene on the core genes should correlate with the effect size of the peripheral gene on the trait.

We have previously observed a striking correlation between LoF burden test effect sizes and Shet on average across traits41. To avoid the confounding effects of selective constraint, we included Shet as a covariate in our linear regression model:

$$\gamma _x \sim \beta _x\to y+S_\mathrmhet,x$$

where \(\beta _x\to y\) corresponds to the regulatory effect of gene x on gene y. We excluded the effects of gene y itself, that is, \(\beta _y\to y\), from the comparison because it does not reflect a trans-regulatory effect. For every expressed gene y, we evaluated the significance of the coefficient for the first term. In some of the plots, the significance level was multiplied by the sign of the coefficient.

Association of program genes with traits

In the program-level analysis, we quantified the average effects of program genes on traits, which we call program burden effect. Program burden effects are the average γ of the genes, which are representative of the program, as determined by the loading for the program in cNMF.

Of note, as a feature of cNMF, the loadings of the genes to the programs are always positive. Thus, the sign of the average γ provides interpretable directional information about the program association with the trait.

As selective constraints are positively correlated with |γ|41, highly conserved programs, such as those essential for cellular survival, could have larger program burden effects. To avoid confounding, we divided the expressed genes in K562 into ten bins based on Shet. We then compared the average γ of the top loading genes with a 10,000 randomly chosen sets of the same number of genes, while matching for the Shet bin. To account for the directional association, we converted the rank of the observed value compared with the random distribution into two-sided P values, while adding the sign of the average γ to calculate the signed association P values.

Here the sign of program burden effects corresponds to the average effects of the LoF of program genes on the trait. Thus, positive program burden effects can be interpreted as a repressing association between program P and the trait.

The results were generally not affected by the choice of the number of top genes (100, 200 and 300). However, for some programs including the haemoglobin synthesis program, where the association with MCH was concentrated on a small number of haemoglobin genes, the association was more pronounced with a smaller number of top genes. Therefore, for visualization of program burden effects and regulator–burden correlation (for example, Fig. 4), we chose 100 for defining the top genes.

Correlation of program regulatory effects with genetic associations

Next, we aimed to quantify the correlation of regulatory effects of genes on the program with γ, which we call regulator–burden correlation.

We calculated the correlation of regulatory effects with trait association signals while accounting for Shet in the same way as the gene-level analysis:

$$\gamma _x \sim \beta _x\to P+S_\mathrmhet,x$$

where \(\beta _x\to P\) corresponds to the regulatory effect of gene x on program P.

For every program, we evaluated the significance of the coefficient for the first term. The significance level was multiplied by the sign of the coefficient for visualization.

Here the sign of \(\beta _x\to P\) corresponds to the effect of the knockdown of gene x on the activity of program P. The sign of γx corresponds to the effect of the LoF of gene x on the phenotype. Thus, a positive regulator–burden correlation can be interpreted as a promoting association between program P and the trait.

Null distribution of burden effects

For visualization of the distribution of burden effects of regulators or program genes (Extended Data Fig. 5h), the expected distribution of burden effect sizes was determined by randomly picking up the same number of genes from non-associated genes 10,000 times and taking their average.

Estimation of causal relationships between programs

While examining the co-regulation patterns across programs, we noticed an asymmetric pattern of co-regulation between programs; that is, the regulators of program A also have effects on program B, but the regulators of program B do not have effects on program A (Extended Data Fig. 5c). Such asymmetry can be explained by a causal directional association from one program to the other. Biologically, this one-way association can be interpreted as positive or negative feedback from one program to the other.

A similar observation—that is, the asymmetric correlation of effects from explanatory variables between two traits—was reported in the GWAS literature96. For instance, when LDL cholesterol causally affects the risk of coronary artery disease, but not vice versa, the effect sizes for risk variants of LDL cholesterol show a strong correlation between the two traits, whereas those for risk variants of coronary artery disease do not show such correlation96.

We adapted the analytic framework for causality from a previous GWAS96 to our case. Specifically, for a pair of programs, P1 and P2, we identified significant regulators (FDR < 0.05) for each. We then calculate \(\rho _P_1\), the Spearman’s rank correlation of effect sizes for P1 and P2, considering only the regulators of P1. We also calculates \(\rho _P_2\) for the regulators of P2. Next, we modelled

$$\hatZ_P_1 \sim N\,\left(Z_P_1,\,\frac1N_P_1-3\right)$$

where \(Z_P_1=\mathrmarctanh(\rho _P_1)\) and \(N_P_1\) corresponds to the number of significant regulators for P1.

Then, we considered four patterns of association, M1: P1 causally associated with P2 (\(Z_P_2\) = 0); M2: P2 causally associated with P1 (\(Z_P_1\) = 0); M3: no relationship between P1 and P2 (\(Z_P_1\) = \(Z_P_2\) = 0); and M4: correlation does not depend on how the regulators were ascertained (\(Z_P_1\) = \(Z_P_2\)).

We fit each model by maximizing the corresponding approximate likelihood. We then selected the model with the smaller Akaike information criterion from the two causal models (M1 and M2) and from the two non-causal models (M3 and M4). Finally, we calculated the relative likelihood of the best non-causal model compared with the best causal model.

$$r=\exp \,\left(\frac\mathrmAIC_\mathrmcausal-\mathrmAIC_\mathrmnon-\mathrmcausal2\right)$$

We treated r < 0.01 as a threshold for causally associated programs. In the case of programs associated with RDW, the causal association from the haemoglobin synthesis program to the mitochondrial program showed r = 8.5 × 10−7, whereas other pairs of programs had r > 0.05 (also refer to Supplementary Note).

Validation with GWAS and trans-eQTL

We downloaded full trans-eQTL summary statistics for selected variants in peripheral blood from the eQTLGen14 website (see the URL in the Code availability section). Here 10,317 trait-associated SNPs were tested for their effects on 19,960 genes that showed expression in blood. Only SNP–gene pairs with a distance greater than 5 Mb were tested. We selected SNPs with significant associations with MCH (P < 5 × 10−8) in the UKB, as well as variants with P > 0.05 as control variants.

Using the program genes defined from cNMF in K562 (the top 100 loading genes for each program), we asked whether GWAS hits for MCH have concordant regulatory effects on the program.

Specifically, for each SNP, we derived the MCH-increasing allele based on β coefficients from GWAS summary statistics, polarized the trans-eQTL Z scores of variants on program genes and calculated the average. We compared the values between GWAS significant variants and control variants using a two-sided Student’s t-test.

Validation of multiple program association with the trait

To test whether jointly modelling multiple programs can explain more of the genetic association signals than modelling with a single program, we conducted a cross-validation analysis. We randomly split 80% of the genes into a training set and 20% into a test set, and fitted regression models to explain the gene effects on the trait (γ) by gene-regulatory effects on the program (or programs) using the training set. We evaluated the variance of γ explained by the model using the test set.

We tested this with the set of multiple programs chosen from the regulator–burden correlations in gene-to-program-to-trait models for MCH and RDW, as well as with the same number of randomly chosen programs, and single program models. The selected multiple program model explained much more variance than any single program model or random combination of programs for MCH and RDW (Extended Data Fig. 6a–c). For IRF, only one program was chosen from the regulator–burden correlation in the gene-to-program-to-trait model, so we did not perform the comparison.

Construction of the gene-to-program-to-trait model

Prevalent co-regulation across programs, as well as feedback, suggested the need to jointly model multiple programs to identify those whose regulation independently explains the trait association signals. In addition, although program burden effects and regulator–burden correlation sometimes converge on the same program, we have observed cases where either only program content or only regulators are enriched in trait association signals, as well as cases in which both program content and regulators are enriched but through different mechanisms. Therefore, we treated program burden effects and regulator–burden correlation separately to identify trait-associated programs included in the model.

Step 1: selection of programs based on regulator–burden correlations

To select programs whose regulators are enriched for the trait association signals, we conducted a stepwise linear regression analysis using the ‘regsubsets’ function in the ‘leaps’ package97 in R. In this analysis, we included gene-regulatory effects on 60 programs \((\beta _x\to P)\), as well as levels of gene constraint (Shet; as defined in ref. 44) as potential explanatory variables, with γx as the dependent variable.

We identified the combination of explanatory variables through exhaustive search to determine the best subsets for predicting γx in a multiple linear regression model with the given number of explanatory variables. Specifically, for MCH, we changed the number of explanatory variables from 1 to 6, and for each number of explanatory variables, we performed an exhaustive search for the combination of programs that explained the most variance of γ.

The number of variables to include in the final model was decided by assessing the variance explained in the model upon changing the number of variables (Supplementary Fig. 2a), along with the significance of the model fit in the subsequent permutation test (Supplementary Fig. 2b). For the MCH model, we opted to include three variables together with Shet: regulators for autophagy, haemoglobin synthesis and G2/M phase cell-cycle programs.

Step 2: selection of programs based on program burden effects

For selecting programs with enriched contents for the trait association signals, we followed the following process. First, for each program, we calculated the program burden effects. That is, we ranked the genes based on their loading and selected the top 200 genes and calculated the average of γ of these genes. This number was determined by the following test for the model fit. Then, we compared it with randomly selected 10,000 sets of genes expressed in K562 while matching for 10 bins of Shet to calculate two-sided enrichment P values. Subsequently, we ranked the programs based on these P values. To determine the number of programs to include in the final model, we varied the number of top programs included and evaluated the model fit in the subsequent permutation test (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Specifically, for the MCH model, five programs were selected: the haemoglobin synthesis program and four programs associated with different phases of cell cycle. These five programs largely corresponded to those that had significant program burden effects after Bonferroni correction in the previous test (Fig. 4c).

Step 3: predicting the signs of associations for the regulators and program genes in the model

After selecting programs from both regulator and program content associations with the trait, we assigned the predicted signs of effects to each gene in the model. Specifically, for regulators, we considered genes that exhibited significant regulatory effects on the selected programs (FDR < 0.05). In cases in which a regulator had regulatory effects on multiple programs, we calculated the total effects of a gene on the model by summing the product of the effect sizes of the selected programs on the trait in the multiple linear regression model (wP) and the gene effects on the program (\(\beta _x\to P\); Extended Data Fig. 6d). The sign of this product was utilized as the regulatory direction of the gene to the trait predicted from the model.

For program contents, we assigned the sign of the association of the program (that is, the sign of the average γ of the top loading genes) to the top 200 loading genes. If a gene belongs to both program and regulator genes, although a such case was relatively rare, we assigned the sign from the program enrichment test because of the potentially larger effect sizes of program function on the trait (Supplementary Note).

Step 4: assessing the directional concordance of the associations of top hits with the model

To assess how well the predicted model can explain the directional genetic associations, we evaluated it in two ways: leave-one-out cross-validation and permutation testing.

For leave-one-out cross-validation, we left out one gene at a time, selected the programs based on program burden effects and regulator–burden correlation using the other genes, and predicted the sign of the left-out gene as described above. We then assessed the enrichment of correctly predicted genes among the top hits (genes with |γ| > 0.1), compared with genes with minimal associations (genes with |γ < 0.01), using Fisher’s exact test. In this test, the enrichment is influenced by both (1) the enrichment of the top genes among the genes selected in the model (significant regulators or program genes in the model), and (2) the accuracy of the predicted signs among the genes in the model. Our result for the MCH model showed that the top genes were enriched in both (1) selected genes in the model (OR = 1.8), and (2) sign concordance (OR = 1.9), with an overall enrichment of P = 5 × 10−5 and OR = 2.2. This result supported the use of Perturb-seq for predicting the directed gene associations.

For the permutation test, we created 20,000 sets of permuted γ by permuting gene labels. We then followed the same program selection and sign assignments processes, while fixing the number of selected programs from both the program burden effects and the regulator–burden correlation. In each permutation, we counted the number of top genes whose sign of association was correctly predicted by the model and evaluated the enrichment over other genes using Fisher’s exact test. Finally, we compared the Fisher’s test P value of the observed data to those of the permuted sets and calculated the permutation P value (Extended Data Fig. 8b,d,f). Similar to leave- one-out cross-validation, we observed that the observed genetic association data had many more concordant genes, along with a higher ratio of concordant to discordant predicted signs than the permuted data (Extended Data Fig. 8a,c,e). The permutation test can evaluate the fit of our model to the genetic association signals.

For the permuted dataset, we slightly modified the way for program selection. Here, instead of matching for Shet, we compared the distribution of γx between the top loading genes and randomly selected genes expressed in K562 using the Mann–Whitney U-test to calculate enrichment P values. Subsequently, we ranked the programs based on these P values and selected the same number of top programs. This helps to greatly speed up the process, although the resulting permutation P value for the model is potentially conservative.

We ran the permutation tests while differing the parameters for the modelling. The model fit to the data was robust to the choice of the number for defining program genes (100, 200 or 300) and to different thresholds for defining high-effect genes (|γ|; Supplementary Fig. 2c). Although the enrichment was not very sensitive to the number of top genes, 200 genes resulted in slightly more stable enrichment across a range of γ thresholds. On the basis of these results, we chose to use the top 200 genes for creating the gene-to-program-to-trait map. In addition, we chose the threshold for |γ| to be 0.1 based on the fit of the model.

Step 5: drawing the gene-to-program-to-trait map

Finally, we aimed to draw a map to interpret the functions of the trait-associated genes. Here we included all the top hits with |γ| > 0.1 whose direction of association was concordant with that predicted from the model into the map (Fig. 5a). When regulators have concordant regulatory effects on multiple programs, we included all paths in the map.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.