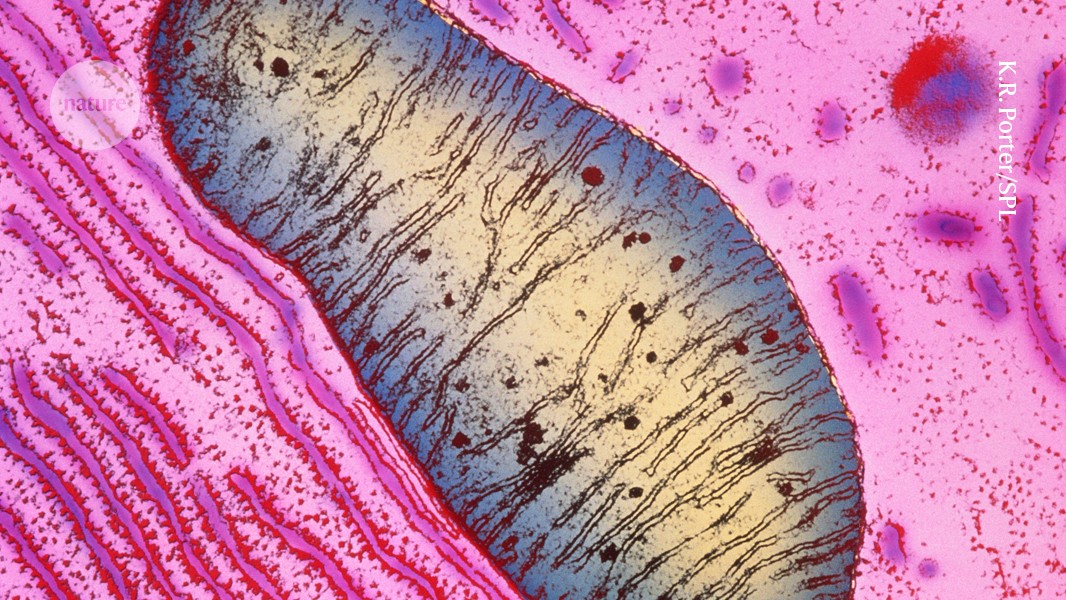

Mitochondria (artificially coloured) are swapped between cells, contrary to an earlier dogma that they stayed with their cells of origin.Credit: K.R. Porter/Science Photo Library

Cancer cells can poison attacking immune cells by filling them with defective mitochondria ― dampening the body’s defensive forces and helping the tumour to evade eradication1.

These findings, published today in Nature, provide the strongest evidence to date that mitochondria, cellular sub-structures that produce energy, migrate in humans and not just in cell and animal models.

“My first thought was that this sounds crazy, like science fiction. But they seem to have the data for it,” says Holden Maecker, an immunologist at Stanford University in California, who was not involved in the research. “This is potentially a totally new biology that we were not looking at.”

Further studies are needed to understand this phenomenon’s frequency and how much it benefits cancer cells, he adds.

Consider the mitochondria

Scientists once thought that each cell’s mitochondria were made by that cell itself, but researchers are increasingly finding that mitochondria can move from one cell to another. In the Petri dish, for example, cancer cells have been found to feed their insatiable appetite for energy by stealing healthy mitochondria from immune cells called T cells2.

To learn more, the authors of the latest work sampled mitochondria from a handful of people with cancer. The researchers compared mitochondria from each person’s cancer cells with those from the same individual’s tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) — immune cells that recognize and invade tumours.

How cancer hijacks the nervous system to grow and spread

The team found that, in three people, both the tumour cells and TILs carried mitochondria with the same mutations, suggesting that misshapen mitochondria might be jumping from diseased to healthy cells.

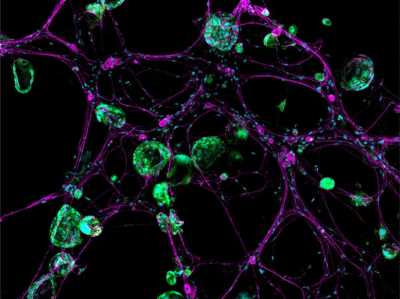

The team engineered cancer cells to carry mitochondria that are speckled with a fluorescent protein. When these cells were grown alongside TILs, the immune cells started harbouring glowing mitochondria after 24 hours. By 15 days, cancer-derived mitochondria had supplanted some immune cells’ native mitochondria almost entirely.

“This challenges our notion of cellular ‘ownership’ of mitochondria,” says Jonathon Brestoff, who studies mitochondria transfer at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri.

Poison power

Tainted TILs were less able to divide and more likely to commit cell ‘suicide’, the team showed in cellular models. In mice with cancer, TILs that had imbibed alien mitochondria showed signs of T cell exhaustion — the loss of cancer-killing potential.