A study of families who have lived through conflict in Syria suggests that genetic imprints of their trauma have been passed to their children and grandchildren.

The research1 focuses on the controversial idea that trauma can leave ‘epigenetic marks’ on a person’s genes that can be passed onto following generations. Not all scientists agree that trauma can be inherited in this way and the mechanism for such inheritance is not known. But the latest research echoes studies of children of survivors of the genocide in Rwanda2 and the Holocaust3 that have turned up similar effects.

“This is a really great attempt to look at the biological imprint of intergenerational trauma,” says Rachel Yehuda, a neuroscientist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City. However, the study “should be seen as a proof of concept”, she adds. It does not explain whether or how such biological marks affect health or behaviour.

In the paper, published in Scientific Reports last month, researchers compared data from 10 families who fled violent events in Syria in the 1980s, and 22 families who fled after the uprising in 2011, with a control group of 16 Syrian families who had not been exposed to war-related violence. The team analysed epigenetic marks — chemical tags on DNA sequences that result from environmental factors including stress — in more than 850,000 DNA regions. Epigenetic marks do not alter DNA sequences but can affect how genes work.

The authors found that adults and children who had been directly exposed to violence in the 1980s and after 2011 had distinctive epigenetic marks in certain DNA regions. In the case of one woman who had witnessed violence in the 1980s, these tags persisted in her daughter and grandchildren. The researchers did not find any of these epigenetic marks among people in the control group. There were 131 participants in total.

The latest findings are “the first to identify epigenetic signatures of trauma across three generations in humans in a controlled research design”, says study co-author Rana Dajani, a molecular biologist at the Hashemite University in Zarqa, Jordan. “Science is about little steps, and this is a little giant step in understanding epigenetic inheritance,” she adds.

Forty years of trauma

Syria’s people have experienced more than 40 years of almost continual trauma. In June 1979, then-president Hafez al-Assad unleashed a crackdown on an attempted rebellion, and in 1982, his troops bombed the city of Hama for days, killing up to 30,000 people.

One of the study participants, now a grandmother, who was pregnant with her daughter at the time, witnessed the crackdown. The study included nine other women whose mothers experienced the violence. Their children also participated in the research.

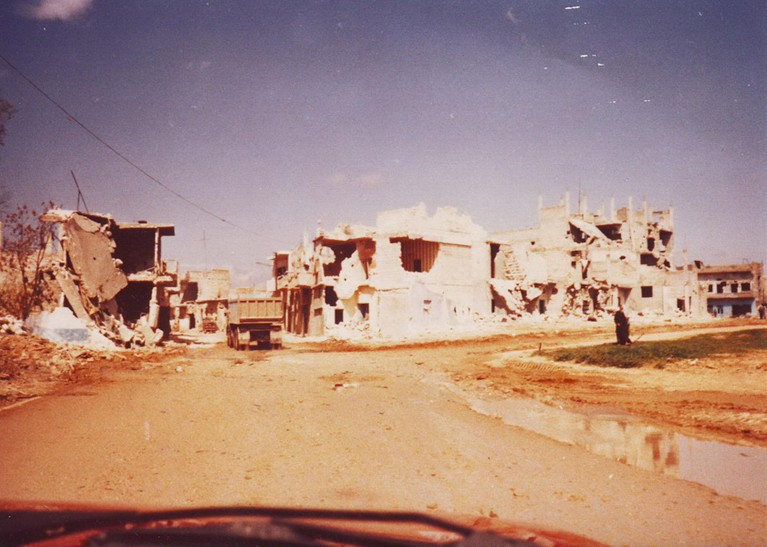

Airstrikes and tank-rounds from the forces of former president Hafez al-Assad flattened many of Hama’s neighbourhoods. Credit: Archive PL/Alamy

Of the study’s participants, 22 mothers and their 20 children witnessed a second period of violence, after the Syrian uprising in 2011. This was when then-president Bashar al-Assad, who fled the country last December, deployed the army and regime-affiliated militias against protesters. The mothers had 19 other children, born after the traumatic events who were also studied.

To understand whether trauma resulting from these violent events had left epigenetic marks, and whether these marks are passed down through the maternal germ line, Dajani and her colleagues focused on patterns of DNA methylation — an epigenetic mechanism in which DNA is tagged with methyl groups. It is one of “the most studied [processes] and we have the technology today to do it”, Dajani says.

Over five years, the researchers searched for study participants from Jordan’s Syrian communities. The team defined a traumatic experience of violence as being severely beaten or persecuted by authorities or militias, seeing a wounded person or fatality, or witnessing someone else being beaten, shot or killed.

They analysed DNA samples from participants’ cheek cells and found that children and women with first-hand traumatic experiences of violence in the 1980s and after 2011 had distinctive methylation tags on 21 DNA regions.

The analysis also revealed tags on 14 DNA regions in the grandmother who witnessed the 1980s violence, as well as in her daughter and grandchild. These tags were also present in the daughters and grandchildren who were the descendants of nine women who witnessed that violence.

“Looking at, at least two — if not three or maybe even four — generations is really crucial. That’s not often done in humans,” says epigeneticist Michael Kobor at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada.

Memory reset

Researchers disagree on whether methylation marks on DNA can pass between generations. This is because during early stages of mammalian development, the genome undergoes the equivalent of a memory reset — a process known as epigenetic reprogramming — that clears out DNA methylation tags.

“All of these marks, almost all of them, are erased when the eggs hit the sperm,” says Kobor. “The biology just doesn’t support DNA methylation as a vehicle of intergenerational transmission,” he adds.