Roughly 2,400 researchers left academia to join Google between 2020 and 2024.Credit: Jason Alden/Bloomberg/Getty

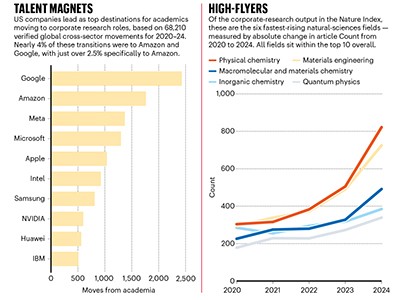

What are the top ten companies that academics go to when taking a research position in the private sector? There are a lot to choose from. The world of commercial research and development (R&D) spans sectors from aerospace and defence to biotechnology and pharmaceuticals. The answer, revealed last week by the Nature Index team, might come as a surprise. Google is the most popular destination, with nearly 2,500 moves from academia between 2020 and 2024. What’s more, the next nine names are also all technology firms, with Amazon, Meta, Microsoft, Apple, Intel, Samsung, NVIDIA, Huawei and IBM completing the list.

As well as being the employer of choice for thousands of researchers and engineers leaving universities, tech companies, some barely a few decades old, are also adding to the sum of R&D in the private sector. But if you expected their financial and research clout to accelerate the growth in R&D spending from businesses, you would be disappointed. The rate of growth in business R&D investment has been falling since 2021. In 2023, the latest year for which we have data, that growth was 2.7% in the countries that belong to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, a group of high-income nations.

What incentives do companies need to publish research?

When businesses invest in R&D, it’s because they want to use the results of research to develop or improve products, services or technologies. The ‘D’ in R&D spending tends to constitute the greater share because it includes product development and testing, which is costlier than research. However, the share of the ‘R’ part seems to be falling, albeit gradually. In the United States today, for example, the share of research expenditure is 20–21% of all R&D spending, down from 28% in 1985.

This matters — for companies, researchers and the wider research ecosystem. A systematic review of the literature summarizes the benefits of peer reviewing and publishing commercial research (D. Rotolo Res. Policy 51, 104606; 2022). In the United States, for example, researchers who wish to patent a discovery or invention can publish that work in the scientific literature up to a year before applying for a patent. Companies can then draw on these studies in their patent applications as part of their evidence that a discovery is novel or an inventive step — two of the requirements for a patent application to succeed. Publication also helps companies to prevent competitors monopolizing particular technologies, and allows them to advertize expertise. If you want a technology to be widely adopted, or to become an industry standard, there are few better ways than to make it available through publication. For smaller firms and start-up companies, publications are a good way to attract funding or investments.

Papers in the open literature allow researchers to showcase their potential to their present and future employers: company R&D directors regularly scour journals to recruit people. Equally, if companies want to attract the best talent from academia, they need to publish — papers are the common currency of research quality that academics understand.

A desire to publish

So why the comparative decline in commercial research as a share of R&D spending? A clue might lie in the nature of modern businesses and how they are, or are not, being regulated. Pharmaceutical companies still dominate Nature Index’s table of the corporations that publish the most in a group of high-quality journals: seven out of the top ten are pharma companies. One reason is that, compared with other sectors, pharma researchers have more incentives to publish in peer-reviewed journals. Papers contribute to the independent validation of the safety and efficacy of new drugs that regulators ultimately need.

These are the top companies and countries for industry research

Innovations from tech businesses do not require approval in the same way, although governments and regulatory bodies are aware that their products can have harmful effects. In 2023, some tentative moves did emerge when the previous US administration directed the National Institute of Standards and Technology to work with tech firms on making artificial intelligence safer. But that effort ended when the current administration came into power.

We are not saying that the tech industry should entirely copy the pharma model, which itself is undergoing review and possible reform of how it is regulated. The sector, for example, has faced criticisms about its influence on clinical trials and regulations. At the same time, there are calls for pharma regulators to apply the lessons learnt during the COVID-19 pandemic, in which fast-track regulatory processes allowed quicker approval of drugs and vaccines. Instead, we are advocating the principle that published science and open data improve research and contribute to safer and more effective outcomes. If, for example, regulators required tech companies to publicly demonstrate safety and efficacy, as they do for pharma companies, that might spur research and publishing in the way it has for pharma.

These are questions that research- and innovation-policy analysts could be studying more. Research output from companies, and indeed business investment in R&D overall, should be higher, considering that the tech sector is attracting so many researchers. Technology’s potential to shape almost every aspect of our lives makes public scrutiny of its research output all the more important.