Credit: Jerry Mason/Science Photo Library

John Gurdon transformed biology by proving that when cells specialize to become a specific type, such as skin or nerve cells, they do so by switching genes on and off, not by losing genetic information. This insight came from his pioneering experiments between the 1950s and the 1970s, when he transferred the nucleus (the part of the cell containing DNA) from frog cells into frog eggs whose nuclei had been removed. Some of the eggs developed into adult frogs, showing that some specialized cells retain the full genetic blueprint to make an entire organism.

Dolly at 20: The inside story on the world’s most famous sheep

He also provided early evidence that, although the number of pluripotent cells — which can become many cell types — declines during development, some persist into adulthood. His work laid the foundation for animal cloning and, decades later, the birth of the first cloned mammal, Dolly the sheep.

Gurdon shared the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Shinya Yamanaka at Kyoto University in Japan, who discovered how to reprogram adult cells into a stem-cell-like state. Together, their discoveries reshaped research into how organisms develop, as well as cell biology and regenerative medicine.

After his early success, Gurdon studied how the nucleus is influenced by the cytoplasm that surrounds it. By transplanting nuclei into eggs and their precursor cells (oocytes), he showed that substances in the cytoplasm control the cell cycle — the sequence of growth and division — and gene activity. He identified chemical triggers for DNA copying and cell division, helping to define how all cells multiply.

Born in southern England in 1933, Gurdon grew up in a comfortable home but struggled at school. At 13, he went to Eton College in Windsor, UK — an experience he later called “intensely uncomfortable”. At 15, he was ranked last out of 250 students in a notorious biology report. His teacher wrote: “He will not listen but will insist on doing his work in his own way. I believe he has ideas about becoming a scientist; on his present showing, this is quite ridiculous.”

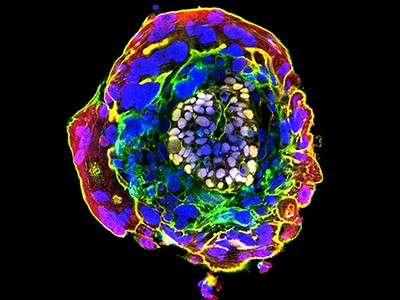

What is an embryo? Scientists say definition needs to change

Following that disaster, Eton excluded him from any further science classes. Christ Church College at the University of Oxford, UK, offered him a place on the strength of his Latin and Greek, on the condition that he studied anything except Latin and Greek. He spent a gap year learning elementary biology and was allowed to switch to zoology. He had a long-standing interest in insects and gained first-class honours in zoology, but the professor of entomology rejected his application to study insects for a doctoral degree. Fortunately for science, Michail Fischberg, a lecturer in developmental biology, offered him a doctoral project studying the embryo of the clawed frog Xenopus, leading to his landmark nuclear-transplantation experiments.