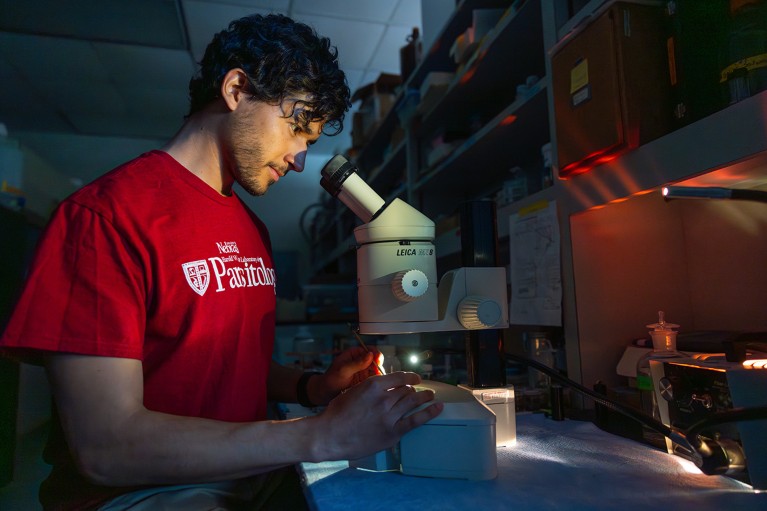

Kevin Liévano-Romero uses a dissection microscope to examine a tapeworm, collected from the small intestine of a giant anteater in Colombia. Credit: Aaron Nix/University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Kevin Liévano-Romero was seven years old when he pooped out his first parasite at home in Bogotá. “Don’t worry, it’s just a worm,” his mother reassured him, before administering a cocktail of local herbs and plants, a battle-tested recipe from her 1970s childhood in rural Colombia. In those days, he says, traditional medicine helped to compensate for a lack of clinics and pharmaceuticals.

The concoction tasted terrible, Liévano-Romero recalls, adding: “I was scared, panicked, but at the same time, fascinated. Those organisms can live in my intestine, and they are so resistant!”

That fascination never left him. Today, Liévano-Romero is a fourth-year parasitology PhD student at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, studying bat parasites. Colombia boasts around 200 bat species, ranking behind only Indonesia, and all of them are likely to host at least one species of parasite, says Liévano-Romero. His research also focuses on the viruses that infect bat parasites, and on how the viruses affect their hosts’ fitness and susceptibility to infections. Because bats can harbour some of the deadliest parasites that exist in tropical places such as Colombia — including Trypanosoma cruzi, which causes Chagas disease — understanding the complex interplay between their parasites and viruses is crucial for public health.

How I connect Colombia’s remote communities to safer water

Most parasitic infections in Colombia are not life-threatening, but they can cause anaemia and stunted growth in children, who are often the most vulnerable. Improved sanitation and hygiene practices have led to a decrease in infections, but a 2012–2014 report from the country’s Ministry of Health and Social Protection and the University of Antioquia found that 81% of children still carried at least one kind of parasite. Among the most common of these were the single-celled parasite Blastocystis, the whipworm Trichuris trichiura and Giardia.

But, unlike most people, Liévano-Romero doesn’t find the bats, the parasites or even the viruses scary: he says their complexity makes them beautiful.

Drawn to wildlife

Liévano-Romero’s nature-loving parents instilled in him a respect for all creatures during a childhood when infestations of fleas and intestinal worms were common. In 2010, aged 16, he joined the National University of Colombia’s prestigious veterinary-medicine programme in Bogotá, becoming the first person in his family to attend university. During his eight-year education, Liévano-Romero volunteered in wildlife clinics. Colombia has one of the highest rates of illegal wildlife trafficking, he says, and he worked with animal victims of that trade, from pygmy hedgehogs to eagles to anteaters. He also ventured into the field with Miguel Rodríguez-Posada, a mammologist affiliated with the university who was studying bats.

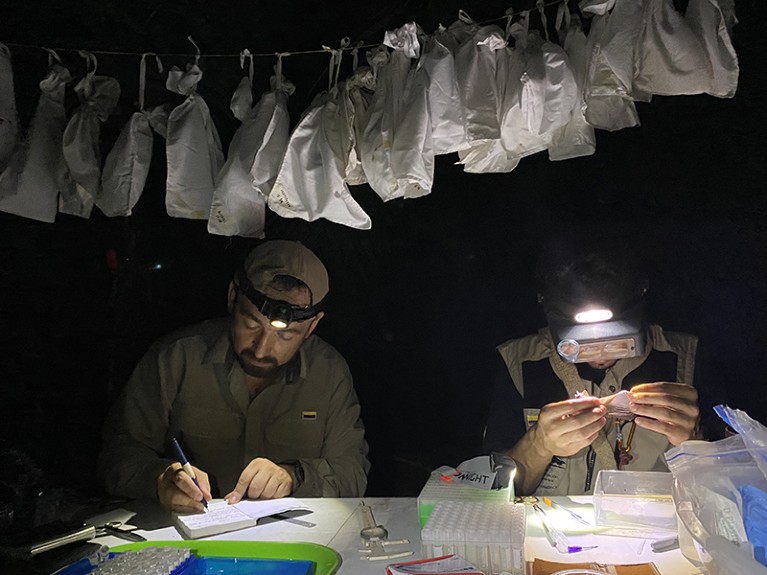

Miguel Rodríguez-Posada (left) identifies bat species during field work in Colombia, and Kevin Liévano-Romero (right) dissects the animals so that he can collect ecto- and endoparasites from them.Credit: Kevin Liévano-Romero

“We went at night to the forest, and when I got the first bat in my hands, I just thought, ‘Wow, this is a fascinating creature … I want to investigate much more.’” A love for his classes in internal medicine and pathology led to a dissertation on bat ectoparasites, such as lice, ticks and bat flies. The research culminated in the first-ever documentation of dozens of bat-parasite species in Colombia1.

After graduating in 2018, Liévano-Romero worked as a vet in Bogotá for three years and helped Rodríguez-Posada with biodiversity field surveys, frequently contracting parasitic infections through contact with animals. He reels off what he was infected with: “all kind of worms … fleas, lice, ticks … blood parasites because of the tick bites or mosquitoes.”

Over-the-counter medications helped him to recover quickly. Infections in big cities such as Bogotá are less common, but they’re ubiquitous in lowland rural areas such as those where his cousins live, and where he does fieldwork. There, traditional medicine is still a more common treatment.

Liévano-Romero has often returned to the concoctions that his family made him as a child when he caught intestinal worms — ‘smoothies’ mixed from the native paico herb (Dysphania ambrosioides), castor oil and garlic. He would also sleep with eucalyptus leaves under the mattress, to ward off parasites in the field. Later, he learnt from Indigenous field guides to spray himself with a liquid mixture of alcohol and tobacco, to achieve the same end.

Kevin Liévano-Romero stands near the summit of the Nevado del Tolima volcano in the Colombian Andes, some 5,000 metres above sea level. Credit: Kevin Liévano-Romero

In cities, parasitic infection is associated with unsafe drinking water, unwashed produce and contaminated meat. A 2018 study found that out of 550 pregnant women across three impoverished residential areas of Bogotá, 41% had intestinal parasites2.

In part owing to high rates of parasitic infection, Colombia has a “robust and strong” academic community pursuing tropical diseases, says Liévano-Romero. According to the World Health Organization, about 15% of Colombia’s government spending in 2023 went on health care. That’s one of the highest proportions in South America. Around one-fifth of the population lives in rural or isolated areas — in forests and mountains, for example — making it hard to monitor these people for parasitic infections.

How researchers can work fairly with Indigenous and local knowledge

So, having grown up knowing intimately about parasites, Liévano-Romero jumped at the opportunity to join a week-long field course on them, involving Rodríguez-Posada. It was there that he met Scott Gardner, a co-organizer of the course and curator of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s Manter Laboratory of Parasitology, which holds the world’s largest university collection of parasites. Liévano-Romero spent the week dissecting mammals, preserving specimens and talking to visiting graduate students from the Manter Lab, one of whom was also Colombian. By the end of the week, he had decided to apply to do a PhD.

“I didn’t think twice, maybe because I was so excited to explore the new world ahead of me,” says Liévano-Romero. “Then I started thinking …’Where is Nebraska, exactly?’”

The anterior end of a newly identified species of trichostrongyloid nematode, described by Kevin Liévano-Romero and Scott Gardner and collected from the small intestine of a Colombian bat.Credit: Kevin Liévano-Romero