Around the world, countries are pushing to electrify transport, which accounts for around 20% of global emissions each year. Electrifying half of the world’s light-duty vehicles could save 1.5 billion tonnes of carbon emissions annually, equivalent to the emissions of Russia1. Doing so would also improve air quality, reducing the rate of asthma attacks, infant mortality and acute bronchitis (see go.nature.com/4onyqhh).

But electric vehicles (EVs) remain unaffordable for most people. Many consumers cite the price of EVs as a barrier to ownership (see go.nature.com/45ffjgj).

EV prices need to fall if they are to be adopted widely enough to curb global emissions. In the European Union, for example, electric cars currently make up just over 1% of the fleet. That figure needs to climb to 20% by 2030 and 43% by 2035 to deliver on the EU’s emissions-reduction targets (see go.nature.com/4ftfnmf).

We need to prepare our transport systems for heatwaves — here’s how

Many governments are increasingly adopting measures to do this. Supply-side policies, which target manufacturers, include tightening emissions standards for petrol and diesel vehicles to make EVs more appealing (a move proposed by the United States in 2023, see go.nature.com/4mj1tq6) and banning the sale of combustion-engine vehicles altogether (as proposed by the EU).

Demand-side policies, targeted at consumers, include exempting EVs from purchase taxes (as Norway implemented in the 1990s) and offering generous incentives for electric-car buyers (enacted by Australia, Canada, the United States and others). Such policies are coming under scrutiny, however, for their high financial cost. For example, under the 2022 US Inflation Reduction Act, taxpayers incur a cost of US$23,000–32,000 per extra EV sold because of the policy2.

All these measures presume that increased demand will stimulate supply, and lead to a virtuous circle in which producers gain technological learning, driving down production costs and therefore EV prices until EVs dominate the market.

Investigating whether this is happening in the United States, we observe that, despite rapid declines in the cost of batteries — the most expensive component of an EV — overall, EV prices have remained stubbornly high. This reality necessitates rethinking policies that see battery costs as the primary impediment to widespread EV adoption. Instead, the identification of other contributors to EV prices is warranted, as are policies that help to lower these prices.

Six roadblocks to net zero — and how to get around them

The main reason often given for why EVs are more expensive than fossil-fuel-powered cars is the cost of the large battery needed to power them, which itself can weigh half a tonne3. Batteries are made using expensive ‘critical minerals’, such as lithium (which costs $15,000 per tonne) and cobalt ($30,000 per tonne). By comparison, steel, the main cost factor for combustion-engine cars, sells for roughly $1,000 per tonne.

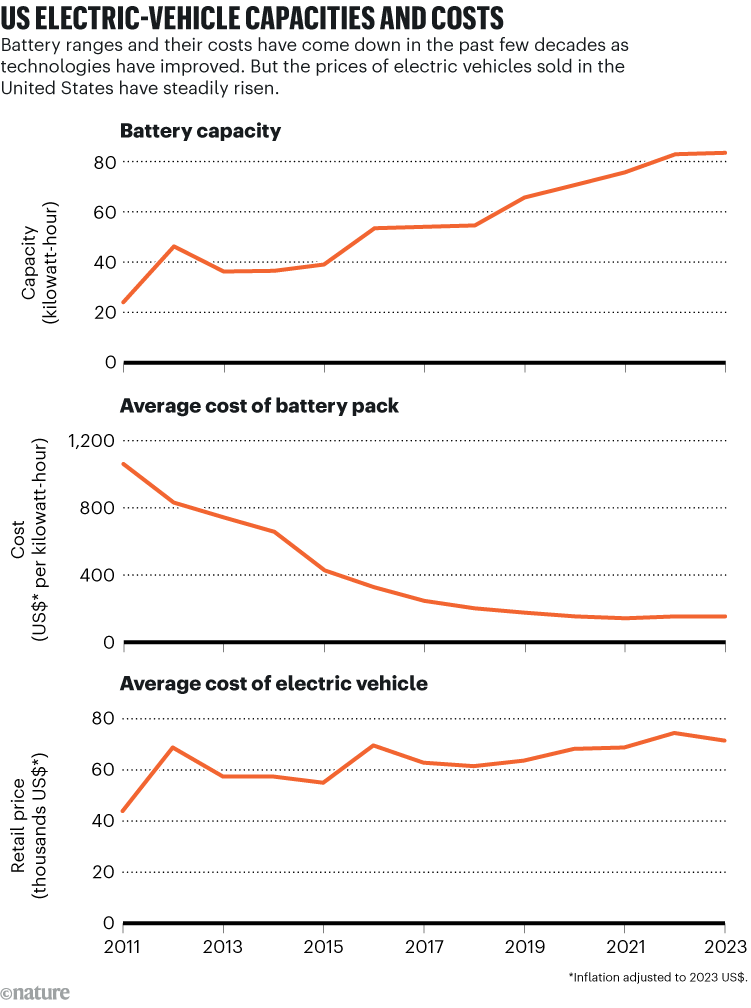

However, over the past few decades, global battery prices have fallen drastically. In 2011, the inflation-adjusted price of an average EV battery was more than $1,000 per kilowatt-hour (kWh). By 2023, that figure had dropped to $139 per kWh. This precipitous decline reflects advancements in battery technology and improvements in battery-cell production, all of which have driven down per-unit production costs.

Lower production costs for firms should mean lower purchasing prices for consumers. However, pricing data from one key market, the United States, over the past few decades suggests otherwise (see ‘US electric-vehicle capacities and costs’). Instead of falling, average EV prices have risen by more than 50%: from $43,872 in 2011, to $71,501 in 2023, although prices fluctuate from year to year.

Sources: Pack-level battery cost: BloombergNEF; Automotive: Cox Automotive, Edmunds, US Environmental Protection Agency.

That’s happened even as the number of sales has increased: between 2011 and 2023, EV sales grew at an average annual rate of 47%. Thus, in the United States, there’s no evidence that cost reductions — realized through battery price falls or production scale-up and technological learning — have been passed down from manufacturers to consumers.

Business and policy environments elsewhere have led to cheaper EVs coming onto the market, notably in China, thanks to government subsidies, lower production costs and fierce competition. The Wuling Hongguang Mini EV, for example, costs $4,700, more than five times cheaper than the cheapest US EV. But it comes with a much smaller battery — just 9.2 kWh compared with the US average of 83.4 kWh. Similarly, in Europe, the Chinese-made Dacia Spring is available for roughly $23,000 with a 27-kWh battery.

No easy answers

Larger battery size is one explanation for why US EV prices are higher4. Bigger batteries allow the car to be driven further, and consumers value greater range5. But larger batteries increase costs, because they require more critical minerals.

However, battery costs alone don’t account for the price differential seen in the US market. Between 2011 and 2023, average battery capacity increased by about 11% annually, while per-kilowatt-hour battery cost declined by 15% annually (see ‘US electric-vehicle capacities and costs’). In other words, the rate of battery-cost declines outpaced efforts by EV manufacturers to increase battery size.

Moreover, battery costs have accounted for a decreasing share of EV prices over time. Whereas in 2011, the battery accounted for, on average, 58% of an EV’s price, by 2017, that had fallen to 21%. In 2023, battery costs accounted for just 16% of an EV’s price.

Aerial view of a lithium mine at Silver Peak, Nevada. Electric-vehicle batteries rely on lithium and other ‘critical minerals’. Credit: Getty

High EV prices could reflect manufacturers’ understanding of their consumer base. EVs are often seen as luxury cars for the rich, so manufacturers can charge more, knowing that those customers are not bothered by the price. However, price gouging is an unlikely culprit for high EV prices. EVs largely remain a loss-making venture. In 2023, Ford Motor lost $4.7 billion on sales of 116,000 ‘Model e’ cars, or an average of $40,525 per vehicle (see go.nature.com/4lcqjkj).

Geopolitical and supply-chain factors are also insufficient to explain the trend. In 2022, for example, Jiten Behl, chief growth officer of Rivian — a US electric-truck maker — blamed rising prices on “inflationary pressure, increasing component costs and unprecedented supply-chain shortages and delays for parts (including semiconductor chips)” (see go.nature.com/40unqt8). Although such extra expenses might explain price increases for a single year, they do not explain EV price rises over decades.