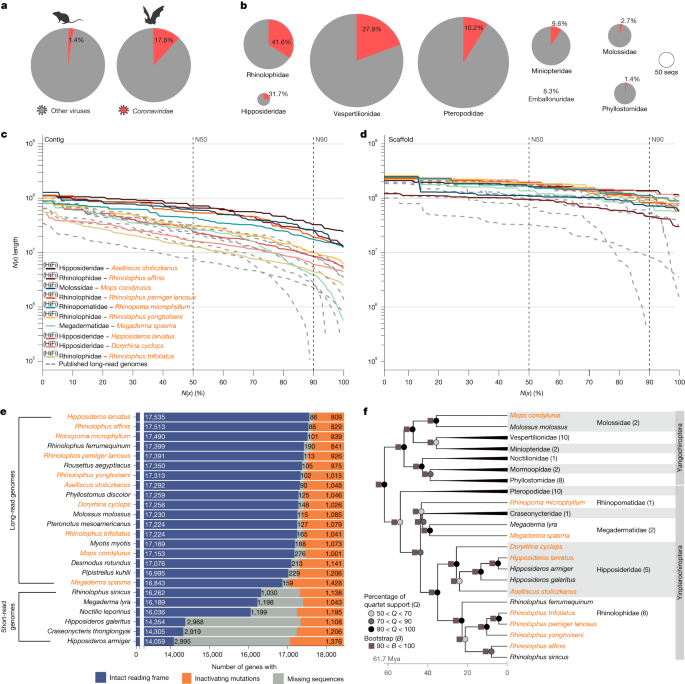

Frequency of coronaviruses in bats and rodents

To assess how often coronaviruses were detected in bats and rodents, and in species belonging to different bat families, we used data from ZOVER6 (last access, 25 January 2023), considering only metagenomic studies (Supplementary Table 1). We curated the bat taxonomic classification used in ZOVER to match the one described in https://batnames.org/. For example, species now recognized as part of the family Hipposideridae were assigned in ZOVER to the former classification in the family Rhinolophidae. Likewise, the family Miniopteridae, representing a separate bat family, was classified as Vespertilionidae. We then built contingency tables and applied a two-tailed Fisher’s exact test to assess statistically significant differences in the prevalence of coronaviruses detected in bats versus rodents, in bats belonging to the family Rhinolophidae versus any other bats, and in bats belonging to the family Hipposideridae versus any other bats. Summary statistics and Fisher’s exact tests were performed in R stats (v.4.1.1)61.

Ethical statements and samples and collecting permits

For eight of the ten sequenced bat species, we used tissue samples from the Royal Ontario Museum mammal collection that had been kept frozen since their collection between 1992 and 2007 (Supplementary Table 2), highlighting the importance of frozen collections for biodiversity genomics62. The eight species are Aselliscus stoliczkanus (from Shuipu Village in China), Doryrhina cyclops (Parc National de TaÏ, Côte d’Ivoire), Hipposideros larvatus (Shuipu Village, China), Rhinolophus affinis (Shiwandashan National Reserve, China), Rhinolophus perniger lanosus (Shuipu Village, China), Rhinolophus yonghoiseni (Endau Rompin National Park, Malaysia), Rhinolophus trifoliatus (Endau Rompin National Park, Malaysia), and Megaderma spasma (Cat Tien National Park, Viet Nam) (Supplementary Table 2). Samples of the remaining two species, Rhinopoma microphyllum (northern Israel) and Mops condylurus (Bregbo, Côte d’Ivoire), were acquired from field expeditions. Samples were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen after being collected and stored at −80 °C until further processing.

The ethical statements of collecting and processing tissue samples for each species followed the procedures required by the following permits:

-

Doryrhina cyclops (ROM-M100513); permit number 81 DPN from Direction de la Protection de la Nature, Côte d’Ivoire;

-

Rhinolophus yonghoiseni (ROM-M113050); Rhinolophus trifoliatus (ROM-M113012); reference number PTN(J) 3/8 from Perbadanan Taman Negara (National Parks Corporation), Johor, Malaysia;

-

Aselliscus stoliczkanus (ROM-M118506), Hipposideros larvatus (ROM-M118627), Rhinolophus affinis (ROM-M116429), Rhinolophus perniger lanosus (ROM-M118548); certificate numbers 2007/CN/ES133-137/KM from the Endangered Species Import and Export Management Office of the People’s Republic of China;

-

Megaderma spasma (ROM-M110751); Number 138/STTN from the Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources, National Center for Science and Technology, Viet Nam;

-

Mops condylurus (ID: 03#106); capture of bats and animal work were performed with the permission of the Laboratoire Central Veterinaire, Laboratoire National d’Appui au Développement Agricole (LANADA), Bingerville, Côte d’Ivoire (no. 05/virology/2016) and the Ministère des Eaux et Forêts (No. 0474/MINEF/DGFF/FRC-aska);

-

Rhinopoma microphyllum; National Parks Authority, permit 2013/04169, IACUC 04-20-019.

Extraction of long genomic DNA

Ultralong and long genomic DNA from various tissues (Supplementary Table 2) was isolated with the Nanobind Tissue Big DNA Kit from Circulomics (part number NB-900-701-01, protocol version Nanobind Tissue Big DNA Kit Handbook v.1.0 11/19) following the manufacturer’s instructions (https://www.circulomics.com/nanobind). In brief, 25–40 mg of liver, spleen or heart tissue was minced to small slices on a clean and cold surface. Tissues were homogenized with the TissueRuptor II device (Qiagen), making use of its maximum settings. After complete tissue lysis, remaining cell debris was removed and the genomic DNA (gDNA) was bound to Circulomics Nanobind discs in the presence of isopropanol. High-molecular-weight (HMW) gDNA was eluted from the nanobind disks in elution buffer. The integrity of the HMW gDNA was determined by pulse field gel electrophoresis using the Pippin Pulse device (SAGE Science). Most of the gDNA was between 10 and 500 kilobases (kb) in length. All pipetting steps of ultralong and long gDNA were done with wide-bore pipette tips. Supplementary Fig. 22 shows an example gel image of the HMW gDNA extraction of Rhinopoma microphyllum.

HiFi library preparation and sequencing

Long insert libraries were prepared as recommended by Pacific Biosciences according to the guidelines for preparing HiFi SMRTbell libraries using the SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit 2.0 (PN 101-853-100, v.03) for Aselliscus stoliczkanus, Hipposideros cyclops, Hipposideros larvatus, Mops condylurus, Rhinolophus affinis, Rhinolophus perniger lanosus, Rhinolophus yonghoiseni, Rhinolophus trifoliatus and Rhinopoma microphyllum. In brief, HMW gDNA was sheared to 20-kb fragments with the MegaRuptor device (Diagenode) and 10 μg sheared gDNA was used for library preparation. The SMRTbell library was size-selected for fragments of 9–13 kb with the BluePippin device according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The size-selected libraries were run on Sequel II SMRT cells with the SEQUEL II sequencing kit 2.0 for 30 h on a SEQUEL II. Circular consensus sequences were called, making use of the default SMRTLink tools. For each species, a total of 65 Gb to 92 Gb of HiFi reads were generated, representing between 27× and 42× effective genome coverage.

Because Pacific Biosciences HiFi sequencing for Megaderma spasma, which was 25 years old, produced very little output despite good DNA and library quality, we used Oxford Nanopore Technologies for this species. Two Oxford Nanopore Technology ligation sequencing libraries were prepared following the manufacturer’s instructions (article number SQK-LSK110, protocol version GDE_9108_v110_revH_10Nov2020). Input gDNA was either unsheared or sheared gDNA (50 kb), using the Diagenode MegaRuptor device as described for Pacific Biosciences HiFi sequencing. After repair of the sheared and unsheared gDNA, Oxford Nanopore Technologies sequencing adapters were ligated to the gDNA fragments and the resulting libraries were enriched for fragments larger than 3 kb. Both libraries were loaded on a Promethion device using R9.4.1 flow cells, generating 173 Gb of reads representing 81× effective genome coverage (12,173,706 total reads, 173,867,637,954 bp total yield, 14,282 bp mean read length, 10,552 bp median read length and 22,685 bp N50 read length).

ARIMA HiC

Chromatin conformation capture was done using the ARIMA-HiC (material number A510008) and the HiC+ kit (material number A410110) and following the user guide for animal tissues (ARIMA-HiC kit, document A160132 v.01 and ARIMA-HiC 2.0 kit, document number A160162 v.00). In brief, about 50 mg of flash-frozen powdered tissue was cross-linked chemically. The cross-linked gDNA was digested with a restriction-enzyme cocktail consisting of two and four restriction enzymes, respectively. The 5′-overhangs were filled in and labelled with biotin. Spatially proximal digested DNA ends were ligated. The ligated biotin-containing fragments were enriched and used for Illumina library preparation, which followed the ARIMA user guide for library preparation using the Kapa Hyper Prep kit (ARIMA document part number A160139 v.00). The barcoded HiC libraries were run on an S4 flow cell of a NovaSeq6000 with 300 cycles. Supplementary Table 2 shows an overview of species and the HiC protocol applied to each.

10× Genomics linked reads

To scaffold and correct base errors in the Megaderma spasma contig assembly, we generated linked Illumina reads with the 10× Genomics Chromium genome application, following the genome reagent kit protocol v.2 (document CG00043, rev. B, 10× Genomics). In brief, 1 ng of long or megabase-size gDNA was partitioned across 1 million gel bead-in-emulsions using the Chromium device. Individual gDNA molecules were amplified in these individual gel bead-in-emulsions in an isothermal incubation using primers that contain a specific 16-bp 10× barcode and the Illumina R1 sequence. After breaking the emulsions, pooled amplified barcoded fragments were purified, enriched and used for Illumina sequencing library preparation, as described in the protocol. Pooled Illumina libraries were sequenced to around 40× genome coverage on an S4 flow cell of a NovaSeq6000 with 300 cycles.

Genome assembly

Contig assembly

Pacific Biosciences CCS (HiFi) reads were generated from the subreads.bam files using the ccs command from the Pacific Biosciences pipeline v.4.2.0 (https://github.com/PacificBiosciences/ccs). For six species (Aselliscus stoliczkanus, Hipposideros larvatus, Rhinolophus affinis, R. perniger lanosus, R. yonghoiseni and R. trifoliatus), we created contig assemblies using hifiasm v.0.13 (ref. 63) with the argument -l0. The primary assembly was created by using purge_dups v.1.2.3 (ref. 64) on the p_ctg.fa output file. The alternative assembly was created by combining the haplotype-purged output from the p_ctg contigs with the a_ctg.fasta created by hifiasm. We then ran purge_dups on this combined alternative assembly to create the final alternative assembly for each species.

For Rhinopoma microphyllum, we assembled the contigs using hifiasm v.0.15.5-r352 with purging argument l2. For Mops condylurus, we used hifiasm v.0.15.4-r432. For both assemblies, we created the primary and alt contigs sets using purge-dups v.1.2.3 as above.

For Doryrhina cyclops, hifiasm created a large number of mis-assemblies joining regions from distinct chromosomes, which could not be reasonably corrected by hand. We therefore ran HiCanu v.2.1 (ref. 65) to create the initial contigs. Because this resulted in an assembly twice the expected size of the genome, we ran purge_dups on the contig assembly using custom cut-offs based on a haploid coverage of 13×: 8, 1, 1, 20, 2, 60 as in ref. 65. The purged output from purge_dups was taken as the primary contig assembly and the haplotype-purge output as the alternative assembly.

For Megaderma spasma, we ran Canu v.2.2 in -nanopore mode and created the primary contig sets using purge-dups as above. We used the basecaller Guppy v.5.0.12 for the libraries PAG52988 and PAG53246, and Guppy v.5.0.13 for the library PAH65658, both in high-accuracy mode.

Scaffolding of Megaderma spasma

We first scaffolded the contigs created by Oxford Nanopore Technologies reads using the 10× Genomics data. To this end, we mapped the 10× Genomics reads using longranger v.2.2.2 and scaffolded using Scaff10× v.4.2 and Break10× v.3.1. Next, we used bionano optical maps to further scaffold the assembly after 10× scaffolding. We created an optical map de novo assembly and then created the scaffold using Bionano Hybrid Scaffold using tools in Bionano Solve v.1.6.1. The resulting assembly was further scaffolded with HiC data, as described below.

HiC scaffolding

To scaffold contigs into chromosome-level scaffolds, we first mapped the Arima V2 HiC data to the genome assemblies using bwa-mem v.0.7.17-r1188 (ref. 66) and filtered reads on the basis of mapping quality and proper-paired alignments following the Arima mapping pipeline from the VGP (https://github.com/VGP/vgp-assembly/blob/master/pipeline/salsa/arima_mapping_pipeline.sh). We then scaffolded using salsa2 v.2.2 (ref. 67) with arguments: -m yes -p yes.

Manual curation

To join the contigs missed by salsa2 and break the joins that were spuriously created, we curated the scaffolds manually. In a few cases, hifiasm created false joins between two different chromosomes in one contig. To break these contigs, we mapped the CCS data to the contigs and found regions of the genome at these spurious joins. Then we identified either regions of low coverage (below 5, often 1 or 2 reads) or highly repetitive regions, in which repetitive tips of contigs from different chromosomes were falsely joined. In these cases, these ambiguous regions were removed from the genome and separate regions of the contigs were rescaffolded.

Polishing assemblies

To polish the final HiFi-based genomes and remove the remaining base errors, we used the CCS reads. To perform a polishing round, we mapped all CCS reads to the scaffolded, gap-closed assemblies using pbmm2 (https://github.com/PacificBiosciences/pbmm2) with arguments: –preset CCS -N 1 and called variants using DeepVariant (https://github.com/google/deepvariant/). We then filtered for sites with genotype 1/1 and a PASS filter value, meaning that all or nearly all the reads support an alternative sequence at this position and passed DeepVariant’s internal filters. With this method, we did not polish any heterozygous or polymorphic regions of the genome, but only those that were incorrect and not supported by any CCS reads. We then corrected base errors using bcftools consensus v.1.12 (ref. 68).

For Megaderma spasma, we first mapped the 10× Genomics linked reads to the assembly using Longranger v.2.2.2. We then called variants using DeepVariant v.1.2.0, filtered the vcf file using Merfin v.1.1-development r197 (ref. 69) and determined the consensus using bcftools consensus v.1.12. We performed two rounds of polishing.

QV metrics

We used Merqury v.1.3 (ref. 70) to estimate QV values. For Megaderma spasma, which was based on Oxford Nanopore Technology reads, we used the 10× Genomics Illumina linked reads. For the other nine HiFi-based assemblies, we used the HiFi reads. For the HiFi-based assemblies, the base accuracy values were two orders of magnitude higher than with previous Pacific Biosciences CLR or Nanopore-based assemblies15,16, although we note that these values are an upper bound because the reads used for assembly were used to estimate the QV, rather than an independent Illumina read dataset. Therefore, it is possible that any remaining errors in the assembly are also in the HiFi reads, which are known to have issues in homopolymer and other simple repeat regions63,65.

Assembly completeness

We used two metrics. First, we used BUSCO v.5.1.1 (Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs; odb10 dataset) with arguments: –mode ‘genome’ to compare the percentage of completely detected near-universally conserved mammalian genes across different assemblies71. Second, to further assess assembly completeness and base accuracy, we used an alternative benchmark metric provided by TOGA 1.0. We thus considered a set of 18,430 genes that probably existed in the placental mammal ancestor, defined as human genes that have an intact reading frame in at least one afrotherian and at least one xenarthran genome21. For each assembly, we determined how many ancestral genes have the following: an intact reading frame (TOGA classification intact, stating that the middle 80% of the coding sequence is present and lacks gene-inactivating mutations); inactivating mutations (TOGA classifications loss and uncertain loss); or missing sequence owing to assembly gaps or fragmentation (TOGA classifications partly intact and missing).

Annotation of transposable elements

To annotate transposable elements (TEs) in the newly sequenced bats, we first generated a de novo repeat library for each genome assembly using a novel pipeline consisting of RepeatModeler, RepeatClassifier, custom scripts (https://github.com/davidaray/bioinfo_tools/blob/master/extract_align.py, RepeatAfterMe (RAM) (https://zenodo.org/record/7076442) and the TE-Aid package included in ref. 72.

In brief, each assembly was subjected to an initial RepeatModeler analysis. Because RepeatModeler will often produce incomplete putative consensus sequences, each putative consensus was subjected to an extension using RAM. These extended consensus sequences were then curated using a custom bash script (TEcurate.sh) that categorized each sequence into one of four categories (LINE, LTR, DNA or Unidentified) using RepeatClassifier, which is part of the RepeatModeler package. TEcurate.sh would then use the TE-Aid package to generate genome coverage plots, self-alignment dot-plots, structure and ORF plots, and copy number estimates.

For any elements clearly categorized as LINE, LTR or DNA, the identity provided by RepeatClassifier was used to generate a unique identifier that included species of origin, the RepeatModeler ID and TE class/family information. For example, hCyc.1.18-#LINE/L1 was discovered in Doryrhina cyclops. Its RepeatModeler ID was rnd-1_family-18 (1.18) and RepeatClassifer identified it as being a LINE1 element. LTR elements were further processed by hand to subdivide them into their LTR and internal segments, as in ref. 73. Consensus sequences with fewer than ten full-length copies were discarded.

TE-Aid plots of elements in the unidentified group were examined by eye to determine likely group membership using structural hallmarks, such as terminal inverted repeats (TIRs), long terminal repeats (LTRs) and sequence characteristics (such as repetitive tails, Helitron-specific CTAG motifs, SINE A-B boxes). Using these characteristics, putative consensus sequences were categorized as LINE, LTR, DNA, SINE, RC (rolling circle) or, when no clear hallmarks were identifiable, unknown.

After all the putative TE consensus sequences were classified and named, all consensus sequences were collapsed with previously known mammalian TEs per a variation of the 80–80–80 rule using USEARCH74 with parameters -id 0.80 -minsl 0.95 -maxsl 1.05 -maxaccepts 32 -maxrejects 128 -userfields query+target+id+ql+tl and comparison to the mammalian TE library from ref. 75. All novel TE consensus sequences have been submitted to the Dfam TE database76. The resulting mammalian TE library was used to mask all assemblies with RepeatMasker. Output was processed to eliminate overlapping hits using RM2Bed.py, part of the RepeatMasker installation package to generate BED files for downstream analyses.

Annotation of microRNAs

Annotation of microRNA (miRNA) genes in the newly sequenced bats was done in a similar way to that in ref. 15. In brief, before miRNA prediction, repetitive and low-complexity regions in each bat genome were masked with the Dfam database (v.3.5; https://www.dfam.org/releases/Dfam_3.5/) using RepeatMasker (v.4.0.6; http://www.repeatmasker.org). For each masked genome, conserved miRNA genes were predicted using the Rfam database (v.14)77 and Infernal (v.1.1.2)78. Infernal uses not only sequence similarity but also miRNA secondary structures for homology searches. We manually inspected ‘spurious miRNAs’ with multiple copies and determined the authenticity of these copies on the basis of the secondary structure we predicted with RNAfold (v.2.4.18)79.

Repeat masking for pairwise genome alignments

To align newly sequenced genomes, we generated a de novo repeat library for each genome assembly using RepeatModeler (http://www.repeatmasker.org/, parameter -engine NCBI). The resulting library was then used to soft-mask the genome using RepeatMasker v.4.0.9 (parameters: -engine crossmatch -s).

Pairwise genome alignments

To infer orthologous genes for phylogenomics and selection screens, we used the human hg38 assembly as a reference species and generated pairwise genome alignments with bats and other mammals as query species. To this end, we used LASTZ 1.04.15 (ref. 80) to obtain local alignments. We used LASTZ parameters (K = 2,400, L = 3,000, Y = 9,400, H = 2,000, and the LASTZ default scoring matrix), which have a sufficiently high sensitivity to align orthologous exons between placental mammals81. Local alignments were chained using axtChain 1.0 (ref. 82) with default parameters except linearGap=loose. We used RepeatFiller 1.0 (ref. 83) (using the default parameters) to add missed repeat-overlapping local alignments to the alignment chains and chainCleaner 1.0 (ref. 84) (using default parameters except minBrokenChainScore = 75,000 and -doPairs) to improve alignment specificity.

Inferring and annotating orthologous genes

To infer orthologues for phylogenomic, selection and gene-loss analyses, we used TOGA 1.0 (ref. 21) (https://github.com/hillerlab/TOGA, commit v.c4bce48). In brief, TOGA uses pairwise genome alignment chains between a reference species (human hg38 assembly) and a query species (other mammals) to infer and annotate orthologous genes and to classify them as intact or lost. TOGA implements a novel paradigm to infer orthologous gene loci that relies largely on intronic and intergenic alignments and uses machine learning to accurately distinguish orthologous from paralogous or processed pseudogene loci. We used the human GENCODE V38 (Ensembl 104) annotation as input for TOGA, providing 39,664 transcripts of 19,456 coding genes.

Annotation completeness

We ran BUSCO with arguments: –mode ‘protein’ on the TOGA annotations to compare the percentage of completely detected almost universally conserved mammalian genes71. Note that applying BUSCO to a gene annotation (annotated proteins) produced by TOGA results in the detection of many duplicated genes because comprehensive annotations frequently include more than one transcript (splice variant) per gene. Because this does not indicate a problem, but rather a comprehensive transcript annotation, we reported only the number of completely detected BUSCO genes in TOGA annotations in Supplementary Tables 3 and 5.

Exon-by-exon alignments of orthologous genes

For phylogenomics and genome-wide selection screens, we used orthologues that are classified by TOGA as intact. TOGA is aware of orthology at the exon level, allowing the implementation of an exon-by-exon alignment to generate a comprehensive set of multiple codon alignments. For each human gene, we considered only the longest isoform. We included only 1:1 orthologues and excluded species for which no or multiple co-orthologues were inferred. Codons with frameshifting insertions or deletions and premature stop codons were masked with ‘NNN’ to maintain the reading frame. For each gene, every orthologous exon was aligned using MACSE v.2 (ref. 85), and all exons, together with codons split by introns, were concatenated into a multiple-codon alignment. Codon alignments were cleaned with HmmCleaner v.0.180750 (ref. 86) using default cost values to identify poorly aligned sequence segments and selectively remove them. From the multiple codon alignments of 19,288 genes, we used 17,130 (about 88%) that included at least 60% of the 115 mammals for phylogenetic inferences and selection screenings.

Phylogenetic and divergence-time estimation

To place the newly sequenced genomes into a bat phylogeny, we reconstructed phylogenetic relationships using whole-gene codon alignments, considering in total 50 bat species (Supplementary Table 3) and 16,860 genes. We also inferred a phylogenetic tree for all 115 mammals using 17,130 genes and used it as input for our selection screen and regression analysis (below).

To estimate a species tree, we followed both a coalescence-based approach, as implemented in ASTRAL v.5.5.9 (refs. 87,88), and a concatenated approach, as implemented in IQTREE v.2.1.3 (ref. 89). For the ASTRAL analysis, input trees were estimated in RAxML v.8.1.16 (ref. 90). Each gene was analysed using three independent replicates, a GTR + GAMMA model and a rapid-hill-climbing algorithm. Gene trees were used as input in ASTRAL with default parameters, and 100 bootstrap replicates were used to calculate the node support. Branch-support values were estimated using a transfer bootstrap expectation implemented in BOOSTER v.1 (ref. 91). For the IQTREE analysis, gene alignments were concatenated into a supermatrix and partitioned using best-fit models of sequence evolution for each gene, determined using ModelFinder (as implemented in IQTREE)92. A maximum-likelihood tree was inferred using IQTREE, with nodal support calculated using 1,000 bootstrap pseudo-replicates.

To estimate time-calibrated trees, we used a penalized likelihood method implemented in treePL93,94 and 17 fossil calibration points95,96. First, one analysis was run to determine the best optimization parameters for treePL, and then a second analysis was run using the optimized values. Fossil calibrations95 were applied to constrain maximum divergence times at relevant nodes (Supplementary Table 4). The time-calibrated phylogenies of bats and mammals are available at http://genome.senckenberg.de/download/Bat1KImmune/.

Selection of non-chiropteran genome assemblies

To obtain a broad genome representation of mammals for our selection screen, we included 95 other mammal and ten bat genomes, representing the main mammalian groups and bat families (Supplementary Table 5). We selected only assemblies for which at least 16,000 ancestral placental mammal genes have an intact reading frame, as determined by TOGA (detailed below) (Supplementary Fig. 7). For Chiroptera, we included the 10 new and 10 previously published bat assemblies; 18 of these 20 bats were assembled from long sequencing reads15,16,97, and the remaining two genomes were assembled from Illumina short-read data98,99 (Supplementary Table 3). For five mammalian orders (Primates, Rodentia, Artiodactyla, Carnivora and Chiroptera), we selected exactly 20 species. The other mammalian orders are represented by fewer species, because there were fewer sequenced genomes available that met our selection criteria. Details and sources of all 115 assemblies are provided in Supplementary Table 5.

Genome-wide unbiased selection screen

To identify genes under positive selection, we used aBSREL23, an adaptive branch-site random-effects likelihood method implemented in HYPHY v.2.5.8 (ref. 100) that infers the strength of natural selection using the ratio of non-synonymous to synonymous substitution rates (the dN/dS metric). The values of dN/dS are interpreted as sites that experience purifying selection (dN/dS < 1), evolve neutrally (dN/dS ≈ 1) or experience positive diversifying selection (dN/dS > 1). For every phylogenetic branch, aBSREL tests if positive selection has occurred by determining whether more-complex models that allow a fraction of the codons to evolve with dN/dS > 1 fit the data best. The method uses the Akaike information criterion to assess the goodness of fit while penalizing increased model complexities (number of parameters). We ran aBSREL in exploratory mode to test all the branches and nodes in the phylogenetic tree for 115 mammals. For each gene, aBSREL corrected for multiple testing over all tested branches using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure. In total, 17,130 genes were screened for selection using our ASTRAL topology as input. Alignments of genes of interest (Supplementary Fig. 14) were inspected by eye to rule out spurious signals resulting from misalignments.

To test whether enrichment results of genes under selection (see below) are representative of mammalian orders or driven by individual species, we did a subsampling analysis. We ran four more selection screens using the same dataset of 17,130 genes but subsampled the 5 mammalian orders with 20 species (Chiroptera, Carnivora, Artiodactyla, Rodentia and Primates) by randomly selecting only 10 species. Orders with less than 20 genomes were not subsampled, thus each subsampled dataset included 115 − 50 = 65 species. Subsamples 1–3 removed species at random, whereas subsample 4 included the 10 species in the five 20-species orders that were left out of subsample 1. For each subsampled set of species, codon alignments were generated and cleaned as for the full dataset, and the same input transcripts were screened for selection.

Gene-enrichment analyses

To explore whether genes under selection in different mammalian orders are enriched in specific functional groups, we performed gene-enrichment analyses, as implemented in gProfiler101,102, using as background all the genes annotated for human reported in Ensembl v.106 (Ensembl Genomes 53, database built on 18 May 2022, e106_eg53_p16_65fcd97). As databases, we used Gene Ontology (http://geneontology.org/) and pathways from KEGG (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/), Reactome (https://reactome.org/) and WikiPathways (https://www.wikipathways.org/index.php/WikiPathways); miRNA targets from miRTarBase (http://mirtarbase.mbc.nctu.edu.tw/) and regulatory motif matches from TRANSFAC (http://genexplain.com/transfac/); tissue specificity from the Human Protein Atlas (https://www.proteinatlas.org/); protein complexes from CORUM (http://mips.helmholtz-muenchen.de/corum/); and human disease phenotypes from Human Phenotype Ontology (https://hpo.jax.org/app/).

It is expected that the more species are included in a mammalian order, the more genes are under selection in at least one of these branches. Therefore, we focused our comparison on the 5 orders that are represented by exactly 20 species. Because P values depend, among other factors, on sample size and the magnitude of the difference, differences in P values can be due to a larger sample size in one group (here, number of selected genes per order), despite having the same or a lower magnitude of the difference. gProfiler calculates the precision value, defined as the proportion of selected genes that are annotated with a particular term, which is listed in Supplementary Table 7 for all enriched terms. For all GO terms that are discussed in the main text as having the strongest enrichment for bats, we confirmed that among the five 20-species mammalian orders, the P value is the lowest and the proportion of selected genes with the GO term is the highest for Chiroptera. For example, immune system process (GO:0002376) has the lowest corrected P value (2.02 × 10−16 for bats, followed by 6.75 × 10−11 for rodents) and also the highest proportion of selected genes annotated with this term (0.184 for bats and 0.17 for rodents).

Correlation between branch length and number of genes under selection

We tested whether there is a significant correlation between branch lengths and the number of genes under selection (note that the aBSREL branch-site model tests for positive selection on every branch in the tree). For branch lengths, we used three independent estimations: first, millions of years from our time-calibrated phylogeny inferred using treePL94 and fossil calibrations (Supplementary Table 4); second, the number of substitutions per neutral site estimated from 4D sites using phyloFit103; and third, the number of substitutions per site estimated from coding regions using IQTREE89. Normal probability plots indicate heavy tails (non-normality), which could be attributed to the unequal error variance of branch-length distribution. We then explored whether remedial measurements such as the Box–Cox approximation can be applied to find appropriate power transformations. In all cases, the likelihood function reaches its maximum when λ ≈ 0.05 (where λ is the transformation parameter, ranging from −5 to 5); we therefore applied a square-root transformation. We fitted linear models with and without transformations and used Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) to select the model(s) that best fit(s) the data given the model complexity104. AIC can be interpreted as a measure of lack of model fit, and to better interpret these relative values, Akaike weights (wAIC) are used to compare models. These weights are analogous to model probabilities because the sum of all wAIC values in a given set of models equals 1. The model with the square root of substitutions per site estimated from coding regions fits the data best with a wAIC = 0.7025 (Supplementary Table 9) and supports a significant correlation with the number of selected genes (r2 = 0.4917, F-statistic = 220.6, 1 and 226 d.f., P < 2.2 × 10−16). A significant correlation between branch length and the number of selected genes was also found for time and number of substitutions per neutral site (Extended Data Fig. 3). Using the best-fit model, we then considered specific immune gene sets and coloured the branches in the phylogenetic reconstruction by the observed number of selected genes minus the expected number based on the model.

To further test whether the number of immune genes under selection is higher in bats than in other mammals, we introduced a categorical taxonomy variable (bats and non-bats). First, we analysed the relationship between the number of immune genes under selection and branch lengths without accounting for different taxonomic groups, corresponding to one intercept and one slope. Second, we included the taxonomic group (bats or non-bats) as an independent correlate corresponding to different intercepts. Third, taxonomic group was included as a correlate, but interacting with the continuous branch-length variable, resulting in two models with two slopes for bats and non-bats, one with one intercept and another with two intercepts. This series was repeated with different branch-length estimates as a covariate. Based on previous analyses, branch-length variables were square-root transformed, with an untransformed analysis included for comparison. Finally, we compared the fit of a simpler frequency distribution than the negative binomial. A Bayesian approach was adopted to run these models, as a flexible way to both fit the model series and generate fit comparison statistics. A negative binomial frequency distribution was used to model the number of immune genes under selection, such that:

$${y}_{i} \sim {\rm{negative}}\;{\rm{binomial}}\,(\lambda =\exp ({l}_{i}),pr)$$

where yi is the count of positively selected genes for branch i, λ is the rate or mean of the Poisson distribution, exp is the inverse logarithmic link function, and (1-pr)/pr defines a rate or shape parameter for the gamma distribution of a mixture of Poisson distributions, which relaxes the expectation of equality of mean and variance of the Poisson distribution. As a result, the negative binomial distribution is usually a better fit to biological data105. With a linear model applied to l:

$$l={\beta }_{0}+{\beta }_{1}X$$

where β0 represents the intercept, which is global for analyses with a single intercept or group-specific for testing bats versus non bats, β1 is the coefficient on branch length, and X represents branch length. Both coefficients are normally distributed. To implement Bayesian sampling for these analyses, we used brms106, a package that enables coding models in R for implementation in the stan statistical language107. For each model, we ran four separate Markov chain Monte Carlo chains using a Hamiltonian Monte Carlo approach. Compared with other Bayesian implementations, the Hamiltonian Monte Carlo approach saves time in sampling parameter spaces by generating efficient transitions spanning the posterior based on derivatives of the density function of the model. We estimated the R2 of all models using the procedure outlined in ref. 108. To compare model fits, we used WAIC (the widely applicable information criterion), which weighs log pointwise predictive density against the expected effective number of parameters as defined in ref. 109 and provides estimates of the standard error of the difference between the best fit and other models.

ISG15 3D structure modelling

To test whether the Cys78 deletion in ISG15 of some bats affects the formation of stable ISG15 homodimers, we first used AlphaFold2 (ref. 110) through ColabFold v.1.3.0 (ref. 111) to infer the structure of the putative ISG15 homodimer of human, Rhinolophus sinicus, Rhinolophus affinis, Rhinolophus yonghoiseni and Doryrhina cyclops. Starting from each ISG15 sequence, ColabFold identified homologous sequences by running MMseqs2 (ref. 112) against the UniRef100 database113 and against a set of environmental sequences114. Structural template information was obtained from the PDB70 database115. Next, the AlphaFold-multimer-v2 model116 was used to infer five structural models of the dimer, with 12 rounds of recycling for model improvement. The resulting models were relaxed using the Amber force field117 and were ranked according to their predicted template modelling score, which we used to identify the best model.

To further investigate the stability of the dimers inferred with AlphaFold2 (Supplementary Fig. 16), we conducted three replicate molecular dynamics simulations for ISG15 of human, R. sinicus and D. cyclops using GROMACS v.2022.1 (refs. 118,119) and the CHARMM36-Jul2021 force field120. More precisely, we prepared each dimer by treating termini as ionized (NH3+ and COO−), assigning appropriate protonation states to amino acids (assuming pH = 7) as determined using PROPKA3 (refs. 121,122) and adding hydrogen atoms. Each dimer was subsequently placed in a periodic dodecahedral box, at a minimum distance of 2.5 nm from each box edge (Supplementary Fig. 17). The box was filled with TIP3P water molecules and with Na+ and Cl− ions as required to neutralize the system (referred to as low salt concentrations below). Following this, we performed energy minimization of the system, and examined the values of the potential energy and the maximum force to ensure that the system was sufficiently relaxed. Next, we applied position restraints on non-hydrogen protein atoms and equilibrated the system in two steps: first, under an NVT ensemble to stabilize the temperature (at 300 K); and second, under an NPT ensemble to stabilize the pressure (at 1 bar) and density of the system. For these, we used the velocity rescaling thermostat123 and the Parrinello–Rahman barostat124,125, set the integration time step to 2 fs and the duration of each equilibration step to 100 ps. As before, we manually examined the temperature, pressure and density to ensure that the system was successfully equilibrated (Supplementary Fig. 18). Finally, we removed the position restraints and conducted production simulations for 1 μs each, recording snapshots of the system every 100 ps. For each species, the three simulations ran for around 6 months on a compute node with 128 cores, summing to a total of about 550,000 CPU hours per species. To explore the effect of higher (physiological) salt concentrations, we conducted three more replicate molecular-dynamics simulations of the ISG15 dimer of Rhinolophus sinicus for 0.5 μs each using a physiological salt concentration (150 mM) (Extended Data Fig. 6).

To analyse the resulting molecular-dynamics trajectories, we combined the snapshots from the three replicate simulations per ISG15 dimer, removed water molecules and ions, and constructed a matrix of pairwise root mean square deviations using Carma v.2.01 (ref. 126). We then clustered the three (human and bats) root mean square deviation matrices according to the Partitioning Around Medoids algorithm127 implemented in the cluster R package v.2.1.3 (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=cluster). This allowed us to identify representative conformations, separately for each dimer. In particular, we set the number of clusters to all possible values between 2 and 10, and selected the clustering with the highest mean silhouette score128. Finally, we extracted the protein snapshots corresponding to the medoid of each cluster and compared them with the initial protein model obtained from AlphaFold (Extended Data Fig. 6). We also produced videos of the simulations using PyMOL v.2.5.0 for all nine molecular-dynamics simulations (Supplementary Videos 1–9).

For the two bat ISG15s, we also used the gmx hbond program with the -contact parameter to examine the contacts among ISG15 monomers (within 5 Å) that were present at each simulation snapshot. This allowed us to investigate how the fraction of native contacts (contacts in the original AlphaFold models that are hence present at the beginning of the simulations) changed across simulation time (Supplementary Fig. 19). As well as native contacts, we also constructed a presence/absence matrix of all contacts between ISG15 monomers during the course of the simulations, which we analysed through PCA (Supplementary Fig. 19).

3D structure modelling of ISG15–PLpro complexes

We used Alphafold2-Multimer in ColabFold111 and the recently identified crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro in complex with human ISG15 (ref. 54) to model the complex of human, R. affinis, R. sinicus, R. yonghoiseni and R. trifoliatus ISG15 and PLpro (displayed as a monomer of each). The ISG15 chain of human from the crystal structure was replaced with full-length human ISG15 (including the remaining C-terminal residues after the cleavage site) then routinely swapped for each species of ISG15. The top model was chosen as previously and predicted template modelling displayed with scaling as per the predicted local distant difference test AlphaFold2 scale in ChimeraX. We used only the catalytic unit of the PLpro monomer (residues 819–2,763) that was previously shown to support independent modelling that reflected well the crystal structure. Supplementary Videos 10, 12, 14, 16 and 18 show the complete view of one molecule of PLpro (catalytic domain) with one molecule of ISG15. Supplementary Videos 11, 13, 15, 17 and 19 (human, R. affinis, R. yonghoiseni, R. sinicus and R. trifoliatus, respectively) represent zoomed views with a 360° rotational spin, highlighting the contact residues (green) calculated in ChimeraX (structure > contacts, VDW overlap, >-0.4, inter-model contacts) between PLpro and ISG15 and the key (homologous) amino acid residues (yellow) identified as contact points in the crystal structure between human ISG15 and PLpro. Snapshots of the entire complex and zoomed regions of the catalytic site with the C-terminal tail of ISG15 are shown in Extended Data Fig. 11.

Investigation of antiviral mechanisms of ISG15 in Rhinolophidae and Hipposideridae

Cell culture

Huh7, HEK293, A549, Vero-76 (CRL-1587, ATCC) and Vero-E6 cells were grown in typical DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS (ExcelBio) and 1% Pen/Strep (Sigma). Importantly, the HEK293 cells used in this study are a HEK293 subclone selected for high production of pseudoviruses. Compared with most HEK293 cells, these subclone cells express the basal machinery of IFN/ISGs and the ISGylation machinery (E1/E2/E3 ligases) is upregulated, which we validated by western blots for ISGylation and its machinery (Extended Data Fig. 10 and Supplementary Fig. 21). RsKT.01 cells (Rhinolophus sinicus) were a gift from Z. Shi and were grown in DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS (Biological Industries) and 1% Pen/Strep (Sigma). For HCoV experiments, an ANPEP/CD13-Flag construct (Sino Biological) was transfected into HEK293 cells (PEI, PolySciences), then selected (mixed pool) with hygromycin for 2 weeks to generate stable cell lines, validated by surface CD13 staining (Sino Biological, 1:2,000 dilution, no permeabilization), and used for consequent infection with HCoV-229E. For SARS-CoV2 experiments, A549-ACE2 cells (human lung adenocarcinoma-derived cells overexpressing human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2)) were provided by the Colpitts laboratory129, and we used the clonal population A549-ACE2 B9. The A549-ACE2 cells were maintained in Ham’s F-12K (Kaighn’s) medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 10 μg ml−1 blasticidin and 1% Pen/Strep.

Huh7 cells were transfected with Lip2000 (Biosharp), HEK293 cells with polyethylenimine (Polysciences), A549 cells with Lipo6000, and Vero-E6 cells with Lipo8000 (Beyotime), each according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All cell lines were tested for mycoplasma and were free of mycoplasma contamination.

Lentiviruses were generated using third-generation HIV-VSV.G lentiviruses with the psPax2 (Addgene plasmid 12260; http://n2t.net/addgene:12260; RRID:Addgene_12260) vector system in HEK293 cells. Geneblocks were synthesized (Beijing Tsingke Biotech or Genscript) according to TOGA annotations for ISG15 (transcript ENST00000649529, aligned to human for validation) and cloned into the pLVX-IRES–mCherry vector under a CMV promoter for direct transfection or lentivirus generation. Lentiviral supernatants were prepared in low-FBS DMEM supplemented with 1% NEAA (Phygene), sodium pyruvate (Thermo Scientific, Gibco) and filtered through a 0.45 µm low-binding PES PVDF filter (Jet Biofil). Lentiviral transduction was done with 100 µl supernatant per well (six-well plates) of cells in 1% FBS with 4 µg ml−1 Polybrene (Biosharp) for 4–6 h; the medium was replaced with 10% serum, and 48–72 h later, cells were sorted for mCherry fluorescence and grown as stable (mix pooled) cell lines to minimize clonal variation. A549 and RsKT cells included a ‘spinfection’ step for centrifuging at 100g for 1 h at 37 °C in six-well plates with the lentivirus.

Myc-tagged ISG15 constructs were synthesized as above to ensure antibody compatibility (Sangon Biotech) (Supplementary Table 27). HEK293-ΔISG15 cells were co-transfected with 200 ng pCDNA3.1-NSP3C (PLpro), 200 ng pCDNA3.1-NSP3L and 300 ng ISG15 Myc-tagged constructs, then cells were induced with 1 µg ml−1 of poly-I:C 24 h after transfection, cell lysates were treated with DSP or BMH (see below) and collected 48 h after transfection. Myc constructs were validated to have minimal impact compared with non-tagged ISG15 constructs (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 23). HEK293-ΔISG15 cells were transfected with 50 ng UBE1L (Addgene, 12438) and UBE2L6 (Addgene, 98380), respectively, and cell lysates were collected 24 h after transfection.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting

To generate ISG15 stable cell lines, lentiviral transduced Huh7, HEK293, A549, RsKT and Vero-E6 cells were sorted by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) using the BD influx system for mCherry-positive cells, normalized against autofluorescence in the respective parental cell line. VSV–GFP load was measured directly by GFP fluorescence intensity. For HCoV-229E, CD13 stable HEK293 cells were stained with 229E N protein (Sino biological, 1:2,000) and Ki67 (Beyotime, 1:500) for 30 min in FACS buffer containing 1× PBS (Gibco), 1% FBS and 1% Pen/Strep, after permeabilization with 0.05% TX-100 in TBS and blocking in 5% BSA in TBS-T. Cells were subsequently rinsed, stained with anti-mouse/rabbit CF-488/568/647 secondary antibody for 15 min (Biotium, dilution 1:10,000), rinsed three times and run on the ACEA Novocyte flow system.

Cell-viability assays

To infer metabolic activity by turnover of ATP, viability assays were performed by adding 10 µl CCK-8 (Transgen Biotech) directly to cells grown in DMEM, 1%FBS, Pen/Strep, incubated for 4 h, then measured over time in a Tecan Spark microplate reader at Abs 450 nm. The background was subtracted and normalized against the control.

Protein conjugation

To detect protein–protein conjugations (cross-linking of amide bonds), di(N-succinimidyl)3,3′-dithiodipropionate (DSP) (Aladdin, PubChem CID: 93313) was used. To detect disulfide-bond-linked proteins, 1,6-bis(maleimido)hexane (BMH) (Aladdin, PubChem CID: 20992), a homobifunctional (sulfide-to-sulfide) sulfhydryl-reactive reagent was used, which facilitated dimer detection. DSP and BMH were dissolved in DMSO (high-purity, Sigma) and diluted in PBS before use at final concentrations of 0.2 mM and 0.1 mM, respectively. After transfection, cross-linkers were added to cells and incubated for 15 min and 25 min, respectively, at 37 °C, before proceeding to the western blot.

Western blots

Cell supernatants and cell lysates were collected before infection or 48 h after infection (HCoV-229E) or 24 h after infection (H1N1 IAV and VSV–GFP). Cells were lysed in Buffer 1 lysis buffer18, supplemented with a phosphatase-inhibitor cocktail (Phygene, PH0321) and protease-inhibitor cocktail (Phygene, PH0320). Collected cell lysates and cell supernatants were mixed with 5× SDS–PAGE loading buffer (Phygene, PH0333) and boiled for 5 min. The protein ladder used was 11–180 kDa Colormixed Protein Marker (Solarbioc) or 15–130 kDa two-colour prestained ladder (Biomed 168), or 10–250 kDa SmartBuffers prestained ladders (N6619); slight size differences were observed between 10% Bis-Tris gels and 4–20% gradient gels (run in Tris-MOPS). Subsequently, cell lysates and supernatants were separated by 10% SDS–PAGE gel, transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, 0.45 μm) and blocked with 5% skimmed milk in TBS. For ISGylation detection, protein samples were mixed with 4× NuPAG LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen, NP0007), separated by NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris gels in running buffer (Invitrogen, NP0001) for 70 min under 120 V, and transferred (Invitrogen, NP000061) for 90 min under 100 V.

The following antibodies were used for detection: rabbit anti-MX1 polyclonal antibody (clone N2C2, Genetex, GTX110256, dilution 1:1,000); rabbit anti-ISG15 polyclonal antibody (middle region, Aviva Systems Biology, ARP59386_P050, dilution 1:1,000); rabbit anti-GAPDH monoclonal antibody (clone 14C10, Cell Signaling, 2118, dilution 1:2,000); rabbit anti-CD13 polyclonal antibody (Sino Biological, 10051-T60, dilution 1:2,000); rabbit HCoV-229E nucleocapsid polyclonal antibody (Sino Biological, 40640-T62, dilution 1:2,000); mouse anti-MYC monoclonal antibody (Sino Biological, 100029-MM08, dilution 1:2,000 for cell lysate and 1:1,000 for cell supernatants); rabbit anti-UBE1L monoclonal antibody (Huabio, HA721228, dilution:1:500); rabbit polyclonal anti-UBE2L6 antibody (Abclonal, A13670); rabbit polyclonal anti-HERC5 antibody (Abclonal, A14889); and HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Transgen Biotech, HS101-01, dilution 1:5,000).

Chemiluminescence was detected using the Enhanced ECL chemiluminescence detection kit (Vazyme) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and subsequently imaged by the LI-COR ODYSSEY FC imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences). Uncropped western blot images are included as Supplementary Data. Densitometry measurements were calculated from FiJI ImageJ software based on equal-size rectangular ROIs (multi-measure) of greyscale TIFF raw files (inverted) for GAPDH (with subtraction of background), ISG15 cell lysates and ISG15 supernatant images. Counts were normalized to GAPDH levels and expressed relative to human cell lysate ISG15 signal (graph for n = 3 independent blots).

Knockout cell-line generation

Single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) of ISG15 were designed following a published protocol130, and subsequently each sgRNA sequence was cloned into plentiCRISPRv2 vector (Addgene plasmid 52961). Scramble non-targeting gRNAs were also designed to serve as a negative control. The gRNA sequences are shown in Supplementary Table 27. Lentiviruses were generated using the method described above. HEK293 cells were first transduced and selected with puromycin (1 µg ml−1) for two rounds of 10 days, followed by western blot of ISG15 for knockout validation.

Virus infections

The HCoV-229E clinical isolate was a gift from J. Zhao (Guangzhou Medical University), and IAV H1N1 PR8 and VSV–GFP (Indiana) were gifts from L. Lu (Zhejiang University). A clinical isolate of SARS-CoV-2 (SARS-CoV-2/SB3-TYAGNC) was used for infection studies following sequence validation using next-generation sequencing131. HCoV-229E was cultured in Huh7 cells or MRC-5 cells. IAV was propagated in A549 or Vero-E6 cells, VSV–GFP in HEK293 cells and SARS-CoV-2 in Vero-76 cells using a previously published protocol131. All stocks were prepared in low serum, filtered for cell debris, aliquoted and titrated in the respective cell line. Virus stocks were thawed once and used for an experiment. A fresh vial was used for each experiment to avoid repeated freeze–thaws. Virus infections were done in 1% FBS at low MOI (0.1) for fluorescent reporter or HCoV-229E TCID50 assays. HCoV-229E assays were run in ten-fold dilutions in low-serum media. H1N1 PR8 IAV infection was done at an MOI of 0.1 in Vero-E6 or A549 cells in 1% FBS for 2 h before removal and replacement with growth media. Supernatant and cell lysates were collected 24 h after infection. Supernatant collection was similarly done after VSV–GFP assays were rinsed after 4–6 h infection, replaced with growth media and followed over time until about 70–80% GFP-positive (overnight).

For SARS-CoV-2 infections, A549-ACE2 cells were seeded at a density of 1.5 × 105 cells per well in a 12-well plate for 24 h. Then the cells were transfected with 200 ng of plasmids encoding bat ISG15 (see above) or vector control for 24 h, followed by infection with ancestral SARS-CoV-2 (SARS-CoV-2/SB3-TYAGNC isolate) at an MOI of 0.01 for 48 h. Control cells were sham infected. Infected or sham-infected cells were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h with gentle rocking every 15 min. After 1 h, virus inoculum was removed, cells were washed with PBS and supplemented with growth medium. Bulk cellular RNA and media from infected and sham-infected cells were collected 48 h after infection using a previously published protocol132. Cells transfected with mCherry_pcDNA3.1(+)-P2A plasmid and infected with SARS-CoV-2 served as a control for plasmid DNA transfection-mediated impact on SARS-CoV-2 replication. All work with infectious SARS-CoV-2 was done in a containment level 3 laboratory at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization, University of Saskatchewan using approved protocols.

Plaque assay

To test direct antiviral function in cells stably expressing ISG15, plaque assays with IAV H1N1 PR8 were done in A549-stable cell lines (as above) by the addition of 50 µl virus to 500 µl low-FBS media (in triplicate) and serial 10-fold dilutions were performed (×8) in 24-well plates. Cells were incubated with virus for 4 h before rinsing and replaced with 2% methyl-cellulose 4000 cP direct overlays (Beyotime) supplemented with 1% FBS and Pen/Strep for 3–4 days.

TCID50 assay

The supernatants from SARS-CoV-2-infected cells were titrated in triplicates on Vero-76 cells using TCID50 assay133. In brief, 1.5 × 104 cells were seeded in each well of a 96-well plate. The plates were incubated overnight to obtain a confluent layer of Vero-76 cells. The next day, medium was taken off the cells and 50 μl 1:10 serially diluted virus-containing supernatant was added to the plates. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. After incubation, the virus-containing supernatant was discarded and 100 μl complete media with 2% FBS was added to the plates. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for three and five days, respectively, and cytopathic effect was observed using a light microscope. TCID50 per ml was calculated using the Spearman and Karber algorithm134,135.

Free ISG15 and point mutations

Based on sequences of ISG15 (ENST00000649529), residues corresponding to Cys78 in human ISG15 were swapped with the codon for alanine (which changes polarity and removes the cysteine disulfide bond) or serine (which has a similar shape and charge but lacks a disulfide bond), whichever required the fewest nucleotide changes. Similarly, Ser77 in R. affinis was changed to a cysteine or a combination mutant replacing the absent lysine at position 77 and swapping the serine for a cysteine residue (at human Cys78). These geneblocks were generated in the same IRES–mCherry backbone. Supernatants from Huh7 cells after transfection or transduction were collected after 24 h or 48 h, respectively, pelleted for cell-debris removal and added directly to SDS–PAGE loading dye for a western blot. Similarly, supernatants were collected after 48 h of HCoV-229E infection. Cell lysates were collected as described previously.

Site-directed mutagenesis

Rhinolophus affinis and R. yonghoiseni ISG15 (LRGG to LRAA) mutants were generated using a QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent) using a previous modification136; see Supplementary Table 27 for primer sequences. Mutations were confirmed by Sanger sequencing at the National Research Council, Canada.

Animal silhouettes

The animal silhouettes used in the figures were downloaded from PhyloPic (https://www.phylopic.org) except for the bat silhouette, which was vectorized by A.E.M.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.