You have full access to this article via your institution.

Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every day? Sign up here.

Chatbot-driven lab robots are automating methods such as protein synthesis.Credit: Du Yu/Xinhua via Alamy

Small trials of autonomous laboratory systems made up of artificial-intelligence-controlled robot ‘scientists’ have sparked debate among researchers over the extent to which such technology could replace humans. These systems, which can automate simple tasks such as liquid transfer, are “going to be the future of biology”, says protein engineer Philip Romero. But the technology currently struggles with tasks that require more dexterity, and might not be useful for experiments without a clear-cut measure of progress, say others.

Reference: bioRxiv preprint (not peer reviewed)

Scientists have identified a giant virus that can hijack a host cell’s protein-making machinery to churn out copies of itself — the first experimental evidence that viruses can co-opt this particular system, which is typically associated with cellular life. To take control, the virus attaches a three-protein complex to the host’s ribosomes — part of the apparatus cells use to make proteins — which gives viral RNA preferential access. Researchers suggest that the virus makes this protein complex using genes that it ‘stole’ from hosts early in its evolutionary history.

Venous sinuses, large veins in the outermost layer of the brain’s protective covering, actively constrict and stretch to drain blood and cerebrospinal fluid from the brain. Researchers also found that these vessels are able to rearrange their borders to accommodate patrolling immune cells, a strange behaviour the team called ruffling. “Having studied vessels now for over 20 years, I’ve never seen a vessel do that before,” says neuroimmunologist and study co-author Dorian McGavern. “The endothelial cells are pliable in a way that is very, very unique.”

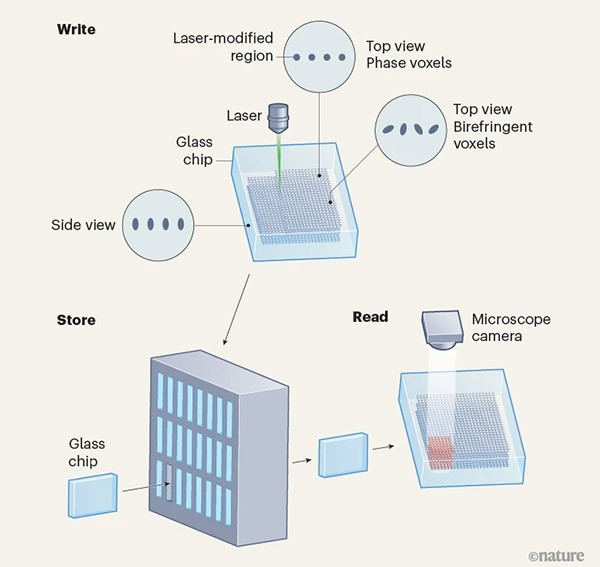

Researchers at Microsoft have created a data-storage system that can remain readable for at least 10,000 years — and probably much longer. The team used a high-energy laser to imprint deformations into a 3D chunk of borosilicate glass, the kind used in ovenware. Each deformation encodes data that can be read out using a microscope. A 12-centimetre wide, 2-millimetre-thick square of the glass can securely store nearly 5 terabytes of data, the equivalent of around 2 million printed books.

An ultrashort laser pulse creates tiny modifications to the optical properties of the glass called voxels, which encode data. A square of glass containing 301 layers of voxels had a storage capacity of 4.8 terabytes. (Nature News & Views | 7 min read)

Features & opinion

Many dogs that enter into training to help people with disabilities don’t graduate into service, often for behavioural or health reasons. With demand skyrocketing, trainers are turning to a combination of cognitive tests, breeding programmes and genetic screening to identify the perfect canine candidates. The complexity of dogs’ behaviour and genetics mean that no one approach is likely to prove a winner, says cognitive ethologist Ádám Miklósi, who also worries that over-optimization of certain traits could cause others to suffer. But even slight improvements in graduation rates would make a big difference, says Brenda Kennedy, chief veterinarian at Canine Companions, a dog-training centre.

Tools used by universities and journals to detect AI-generated text are blunt instruments that risk flattening academic writing, argues social psychologist Bo Hu. To avoid being flagged, authors might exclude certain words or punctuation that they deem indicative of AI use, but doing so could make manuscripts more homogenous. Institutions should judge integrity based on verifiable process evidence rather than language used in the final product, Hu writes. “We should ensure that the future of science is shaped by human creativity rather than by the fear of being mistaken for a machine.”

Nature Human Behaviour | 4 min read

In Inari, a small village in Finland, educators have pulled the Indigenous language Inari Sámi from the brink of extinction using an initiative called language nests. First trialled in New Zealand to preserve Māori languages, these nests aim to immerse children in Indigenous cultures at school, complete with traditional room decorations and tableware. Since they were first introduced in Finland in 1997, the number of native Inari Sámi speakers has only increased by around 100, but “every new speaker counts”, says Fabrizio Brecciaroli, a proofreader at the Inari Sámi Language Association. “If the Inari Sámi language disappears, there won’t be Inari Sámi people anymore.”

Today, as it rains in the UK for the umpteenth day in a row, I’m once again reaching for my coat and umbrella. One trick I’m going to try to make going out in the rain more bearable is thinking of something I can look forward to afterward, such as a hot bath or warming meal, as suggested by psychologist Luke Hodson.

When I’ve finished my rainy commute home, I’m looking forward to reading your feedback on this newsletter. Please send your thoughts, positive or constructive, to [email protected].

Thanks for reading,

Jacob Smith, associate editor, Nature Briefing

• Nature Briefing: Careers — insights, advice and award-winning journalism to help you optimize your working life

• Nature Briefing: Microbiology — the most abundant living entities on our planet — microorganisms — and the role they play in health, the environment and food systems

• Nature Briefing: Anthropocene — climate change, biodiversity, sustainability and geoengineering

• Nature Briefing: AI & Robotics — 100% written by humans, of course

• Nature Briefing: Cancer — a weekly newsletter written with cancer researchers in mind

• Nature Briefing: Translational Research — covers biotechnology, drug discovery and pharma