Dataset acquisition for mouse CD8+ T cell state multi-omics atlas

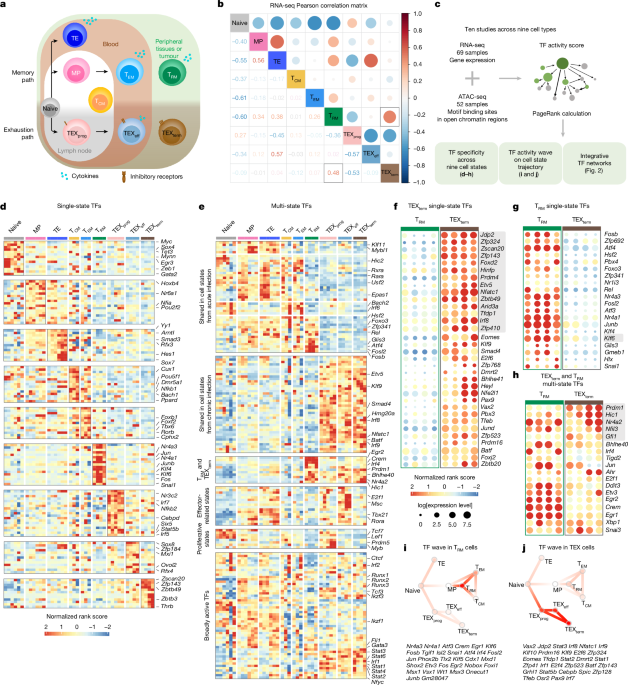

CD8+ T cell samples were collected from ten datasets, including those generated in this study (Extended Data Fig. 1e). In total, we analysed 121 experiments, comprising 52 ATAC-seq and 69 RNA-seq datasets, which were integrated to generate paired samples and served as input for the Taiji pipeline. The samples encompassed nine distinct CD8+ T cell subtypes: naive, TE, MP, TRM, TEM, TCM, TEXprog, TEXeff and TEXterm. Cell states were defined on the basis of established surface marker combinations and LCMV-specific tetramers, including IL7R, KLRG1, PD1, SLAMF6, CD101, Tim3, CD69, CD103, H2-Db LCMV GP33–41 and H2-Db LCMV GP276–286 or congenic markers for P14 (T cell receptor (TCR) specific for the LCMV GP33–41 peptide CD8+ T cells), in the context of either acute (LCMV–Armstrong) or chronic (LCMV–Clone 13) infection models. A complete summary of dataset sources, accession numbers, infection conditions and corresponding cell state definitions (sorting gates) is provided in Supplementary Table 1 and Extended Data Fig. 1e.

TF regulatory networks construction and visualization

To perform integrative analysis of RNA-seq and ATAC-seq data, we developed Taiji v.2.0, which allows visualization of several downstream analysis–TF wave, TF–TF association and TF community analysis. Epitensor was used for the prediction of chromatin interactions. Putative TF binding motifs were curated from the latest CIS-BP database61. In this analysis, 695 TF genes were identified as having binding sites centred around ATAC-seq peak summits. The average number of nodes (genes) and edges (interactions) of the genetic regulatory networks across CD8+ T cell states were 15,845 and 1,325,694, respectively, including 695 (4.38%) TF nodes. On average, each TF regulated 1,907 genes, and each gene was regulated by 22 TFs.

Identification of single-state and multi-state TF genes

We first identified universal TF genes with mean PageRank across nine cell states ranked as top 10% and coefficients of variation less than 0.5. In total, 54 universal TF genes were identified (Supplementary Table 1). The remaining 641 TF genes were candidates for single-state TF genes. To identify single-state TF genes, we divided the samples into two groups: target and background. The target group included all samples belonging to the cell state of interest, and the background group comprised the remaining samples. We then performed the normality test using Shapiro-Wilk’s method to determine whether the two groups were distributed normally, and we found that the PageRank scores of most (90%) samples followed a log-normal distribution. On the basis of the log-normality assumption, an unpaired t-test was used to calculate the P value. A P value cut-off of 0.05 and log2 fold change (log2FC) cut-off of 0.5 were used for calling lineage-specific TFs. In total, 255 specific TF genes were identified (Supplementary Table 2). Depending on whether the TF gene appeared in several cell states, they could be divided further into multi-state TF genes (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Table 2) and 136 single-state exclusive TF genes (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Table 2). Out of 255 single-state TF genes, 84 appear in TEXterm or TRM cells. To identify the truly distinctive TF genes between TEXterm and TRM, we performed a second round of unpaired t-tests, between only TEXterm and TRM cells (Supplementary Table 3). The same cut-offs, that is, P value of 0.05 and log2FC of 0.5, were applied to select TEXterm single-taskers and TRM single-taskers. Out of 84 TF genes that did not pass the cut-off, 30 were identified as TEXterm and TRM multi-taskers. The full workflow is summarized in Extended Data Fig. 2a.

Identification of transcriptional waves

Combined with previous knowledge of the T cell differentiation path, TF waves are combinations of TFs that are particularly active in certain differentiation stages, revealing possible mechanisms of how TF activities are coordinated during differentiation. To be more specific, we clustered the TFs based on the normalized PageRank scores across samples. First, we performed principal component analysis (PCA) for dimensionality reduction of the TF score matrix. We retained the first ten principal components for further clustering analysis, which explained more than 70% of the variance (Extended Data Fig. 3b; left panel). We used the k-means algorithm for clustering analysis. To find the optimal number of clusters and similarity metric, we performed Silhouette analysis to evaluate the clustering quality using five distance metrics: Euclidean distance, Manhattan distance, Kendall correlation, Pearson correlation and Spearman correlation (Extended Data Fig. 3b; right panel). Pearson correlation was the most appropriate distance metric, as the average Silhouette width was highest of all five distance metrics. On the basis of these analyses, we identified seven distinct dynamic patterns of TF activity during immune cell development. We further performed functional enrichment analysis to identify gene ontology (GO) terms for these clusters.

TF–TF collaboration network analysis and visualization

To build the TF–TF association networks, we first defined a set of relevant TFs for each context (TEXterm and TRM) by combining cell state-important and single-state TF genes, resulting in 159 TFs for TEXterm and 170 for TRM cells. The analysis was based on a TF–regulatee network derived from Taiji, where we first consolidated sample networks by averaging the edge weights for each TF–regulatee pair. To reduce noise, regulatees with low variation across all TFs (s.d. ≤ 1) were removed. Subsequently, a TF–TF correlation matrix was generated by calculating the Spearman’s correlation of edge weights for each TF pair across their common regulatees. From this matrix, we constructed a graphical model using the R package ‘huge’62, which uses the Graphical Lasso algorithm and a shrunken empirical cumulative distribution function estimator. An edge between two TFs was established if their correlation was deemed significant by the model, controlled by a lasso penalty parameter (lambda) of 0.052. This value was chosen as it represents a local minimum on the sparsity lambda curve, resulting in approximately 15% of TF–TF pairs being connected. To validate this method, we estimated the false discovery rate by generating a null model through random shuffling of the TF–regulatee edge weights. Applying our algorithm to this null data identified zero interactions, confirming that our approach has a very low false discovery rate.

TF community construction and visualization

Following construction of TF–TF association networks, we identified functionally related TF communities within each network. We applied the Leiden algorithm63, using modularity as the objective function and setting the resolution parameter to 0.9, as this value achieved the highest clustering modularity in our analysis. This procedure identified five distinct communities for each context (TEXterm and TRM). The final networks, with their detected communities, were visualized using the Fruchterman–Reingold layout algorithm64 to spatially represent the TF–TF association structure.

Pathway enrichment analysis

The enriched functional terms in this study were analysed by the R package clusterProfiler v.4.0.5. We used the GO database, the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database and the Molecular Signatures Database for annotation. For GSEA, the genes were first ranked by the mean edge weight in corresponding samples and H, C5, C6 and C7 collections from the Molecular Signatures Database were used for annotation. A cut-off of P < 0.05 was used to select the significantly enriched GO terms and KEGG pathways.

Heuristic score calculation through integration of the TF regulatory network and perturb-seq

We reasoned that (1) log2FC in expression due to TF KO and (2) TF–gene regulatory edge weights could be combined to provide heuristic scores for the regulatory effect of a TF on a target gene. For each guide RNA KO, Seurat’s FindMarkers() function was used to quantify log2FC in the expression of a gene with respect to the gScramble condition. Heuristic scores were calculated for each TF–gene pair by multiplying the gene log2FC with the corresponding edge weight from the Taiji analysis. Regulatees of a TF were annotated as high-confidence if the magnitude log2FC of the regulate exceeded 0.58 (corresponding to a fold change of 1.5 or its reciprocal) and if the edge weight belonged to the upper quantile of all edge weights attributed to the TF. The sign of the log2FC was used to determine whether the TF activated or repressed each target gene.

Human TF activity and cell-state selectivity analysis

Taiji-based analysis of human multi-omic datasets

TF activity was inferred using the Taiji pipeline applied to matched scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq datasets from various human cancers, including ccRCC (n = 2; PRJNA768891, GSE240822), GBM (GSE240822), BCC (GSE123814, EGAS00001006141), HNSCC (GSE139324, EGAS00001006141), HCC (GSE125449, EGAS00001006141) and RCC (PMID: 30093597; EGAS00001006141). Cell types were annotated using canonical marker gene expression and categorized into six main CD8+ T cell states: TEX, TEXProg (progenitor exhausted), TEff (effector), TRM, TCM/naive and proliferating. PageRank scores derived from Taiji were log-transformed, averaged within each T cell category, and then standardized using z-score normalization. Results were visualized with a focus on TF gene activity in TRM and TEX populations.

TF gene expression comparison across human CD8+ T cell states

To assess TF gene expression across diverse T cell states, raw count matrices from a published pan-cancer CD8+ T cell atlas (GSE156728) were reprocessed using Seurat’s standard workflow. The dataset encompassed T cells from 11 tumour types, including BC, BCL, CHOL, ESCA, FTC, MM, OV, PACA, RC, THCA and UCEC. Cell type annotations provided by the original study were retained and mapped to the following broad categories: TRM, TEX, TEM (effector memory), TM (memory), naive and TK (cycling). Seurat’s AverageExpression function was used to compute average logCPM expression for each TF gene in each T cell category, followed by z-score normalization. Data visualization emphasized comparisons between TRM and TEX subsets.

Mice and infections

C57BL/6/J, OT-1 (C57BL/6-Tg(TcraTcrb)1100Mjb/J), B6.Cg-Rag2tm1.1Cgn/J and CD45.1 (B6.SJL-PtprcaPepcb/BoyJ) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. P14 mice have been described previously. Cas9 P14 mice were generated by crossing P14 mice with B6(C)-Gt(ROSA)26Sorem1.1(CAG-cas9*,-EGFP)Rsky/J (Jackson Laboratories). Animals were housed in specific-pathogen-free facilities at the Salk Institute and University and at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were infected with 2 × 105 plaque-forming units (PFU) LCMV–Armstrong by intraperitoneal injection or 2 × 106 PFU LCMV Clone-13 by retro-orbital injection under anaesthesia.

Viral titres

LCMV fluorescence focus unit titration was performed seeding Vero cells at a density of 30,000 cells per 100 µl in a 96-well flat-bottom plate in DMEM + 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) + 2% HEPES + 1% penicillin-streptomycin. On the next day, tissues were homogenized on ice, spun down at 1,000g for 5 min at 4 °C and supernatants or serum were diluted in tenfold steps. Diluted samples were added to Vero cells and incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for around 20 h. Subsequently, inocula were aspirated and wells were incubated with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature before washing with PBS. VL-4 antibody (BioXCell) was conjugated using the Invitrogen AF488 conjugation kit and added to the wells in dilution buffer containing 3% BSA and 0.3% Triton (ThermoFisher Scientific) in PBS. Cells were incubated at 4 °C overnight before washing with PBS and counting foci under the microscope. The number of focus forming units was calculated using the formula: focus forming units per millilitre = number of plaques/(dilution× volume of diluted virus added to the plate).

Cell isolation

Spleens were dissociated mechanically with 1-ml syringe plungers over a 70-µm nylon strainer. Spleens were incubated in ammonium chloride potassium buffer for 5 min. For isolation of small intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes, Peyer’s patches were first removed by dissection. Intestines were cut longitudinally and then into 1-cm pieces and washed in PBS. Pieces were incubated in 30 ml HBSS with 10% FBS, 10 mM HEPES and 1 mM dithioerythritol with vigorous shaking at 37 °C for 30 min. Supernatants were collected, washed and isolated further using 40%/67% discontinuous Percoll density centrifugation for 20 min at room temperature with no brake.

Cell lines and in vitro cultures

B16-GP33 melanoma cell lines were cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen) with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 250 μg ml−1 G418 (Invitrogen, catalogue no. 10131027). The MCA-205 tumour line (Sigma) was maintained in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS, 300 mg l−1 l-glutamine, 100 U ml−1 penicillin, 100 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 μM non-essential amino acids, 1 mM HEPES, 55 μM 2-mercaptoethanol and 0.2% plasmocin mycoplasma prophylactic (InvivoGen). All the tumour cell lines were used for experiments when in the exponential growth phase. For in vitro T cell culture, splenocytes were activated in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen) containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 2 mM l-glutamine, 0.1 mg ml−1 GP33, beta-mercaptoethanol 50 mM and 10 U ml−1 IL-2.

Tumour engraftment and treatment of tumour-bearing mice

A total of 3 × 105 B16-GP33 (Fig. 5a), 5 × 105 B16-GP33 tumour cells (Fig. 5n,o) were injected subcutaneously in 100 μl PBS. Around 0.5–1 × 106 Cas9+ P14 T cells with CD45.1 markers were transferred to tumour on day 7 without pre-radiation of tumour-bearing mice. Tumours were measured every 2–3 days post-tumour engraftment for indicated treatments and sizes calculated. Tumour volume was calculated as volume = (length × width2)/2. For antibody-based treatment, tumour-bearing mice were treated with anti-PD1 antibody (200 µg per injection, clone RMP1-14, BioXcell) twice per week from day 7 post-tumour implantation. Tumour growth was measured twice per week with calipers. Survival events were recorded each time a mouse reached the endpoint (tumour volume greater than or equal to 1,500 mm3). Tumour weights were measured on day 23 for Fig. 5a and on day 25 for Fig. 5m–o. All experiments were conducted according to the Salk Institute Animal Care and Use Committee and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Animal Care and Use Committee.

Tumour digestion and cell isolation

For the data shown in Fig. 5, tumours were minced into small pieces in RPMI containing 2% FBS, DNase I (0.5 µg ml−1; Sigma-Aldrich), and collagenase (0.5 mg ml−1; Sigma-Aldrich) and kept for digestion for 30 min at 37 °C with 70-µm cell strainers (VWR). Filtered cells were incubated with ammonium chloride potassium lysis buffer (Invitrogen) to lyse red blood cells, mixed with excess RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen) containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and centrifuged at 400g for 5 min to obtain a single-cell suspension.

Proteasome activity analysis

For experiments involving the Proteasome Activity Probe (R&D systems), cells of interest were incubated with the probe at concentration of 2.5 mM for 2 h at 37 °C in PBS. Samples were washed and then stained with Zombie NIR viability dye (Biolegend) in PBS at 4 °C for 15 min. Samples were then stained with some variation of the following antibodies for 30 min in fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer on ice: CD45-BV510 (BD Biosciences), CD45.2-BV510 (Biolegend), CD45.1-PE-Cy7 (Invitrogen), CD4-APC Fire 810 (Biolegend), CD11b-Alexa Fluor 532 (Invitrogen), CD8-Spark NIR 685 (Biolegend), CD44-Brilliant Violet 785 (Biolegend), CD62L-BV421 (BD Biosciences), PD1-BB700 (BD Biosciences), TIM3-BV711 (Biolegend), LAG3-APC-eFluor 780 (Invitrogen), SlamF6-APC (Invitrogen), CD39-Superbright 436 (Invitrogen), CX3CR1-PE/Fire 640 (Biolegend), CD69-PE-Cy5 (Biolegend), GITR-BV650 (BD Biosciences) and CD27-BV750 (BD Biosciences). Samples were collected on a Cytek Northern Lights and analysed using Cytek SpectraFlo software.

Tumour experiment for proteasome assay

For the data shown in Fig. 2, MCA-205 fibrosarcomas (2.5 × 105) were established by subcutaneous injection into the right flank of C57BL/6 mice. After 12–14 days of tumour growth, spleens, draining lymph nodes and tumours from groups of mice were collected and tumours were processed using the Mouse Tumor Dissociation Kit and gentleMACS dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For purification experiments, samples were pre-enriched using the EasySep Mouse CD8+ T Cell Isolation Kit (Stemcell Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, stained with Live-or-Dye PE Fixable Viability Stain (Biotium) and CD8a-APC (Invitrogen) and live CD8+ cells were sorted using the FACSAria II cell sorter. CD8+ spleen and pooled TIL samples were washed in PBS and frozen for RNA-seq analysis. For adoptive cellular therapy experiments, B16-GP33 melanomas were established subcutaneously by injecting 5.0 × 105 cells into the right flank of CD45.1 mice and tumour-bearing hosts were irradiated with 5 Gy 24 h before T cell transfer. By contrast, mice used in the experiments shown in Fig. 5 were not irradiated before T cell transfer. After 7 days of tumour growth, 1.5 × 106 CD45.2 OT-1 T cells and 1.5 × 106 CD45.1/CD45.2 P14 T cells were infused in 100 μl PBS into the tail vein in tumour-bearing mice. Tumours were collected 14 days after adoptive cell transfer and CD8 TILs were analysed for proteasome activity. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Animal Care and Use Committee.

Proteasomehigh/proteasomelow T cell adoptive transfer experiment

For the adoptive transfer experiment involving proteasomehigh and proteasomelow tumour-specific OT-1 T cells (Fig. 2l), whole splenocytes from OT-1 mice were activated with 1 μg ml−1 OVA_257–264 peptide and expanded for 7 days in the presence of 200 U ml−1 rhIL-2 (NCI). On day 7, OT-1 cells were FACS-sorted based on proteasome activity to isolate proteasomehigh and proteasomelow OT-1 populations. A total of 2.5 × 105 sorted OT-1 cells were injected into C57BL/6 mice bearing B16F1-OVA melanomas. Tumours were established by subcutaneous injection of 3 × 105 B16F1-OVA cells into the right flank 7 days before T cell transfer. Recipient mice were preconditioned with 5 Gy total body irradiation 24 h before adoptive transfer. Tumour growth was measured every other day with calipers.

For Extended Data Fig. 5c, MCA-205 fibrosarcomas (2.5 × 105) were established by means of subcutaneous injection into the right flank of C57BL/6 mice. After 14 days of tumour growth, live CD45+CD8+CD44+PD1+ T cells were sorted from tumours on the basis of proteasome activity (high versus low) using the FACSAria II cell sorter. A total of 2.5 × 104 cells were then injected into the 2-day MCA-205-bearing RAG2−/− hosts (n = 5 per group) and tumour growth was monitored every other day starting on day 4. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Animal Care and Use Committee.

Retrovirus transduction and adoptive transfer

For overexpression of the gRNA retrovirus vector, 293T cells were transfected with the Eco-helper and MSCV gRNA vectors. At 48 h and 72 h later, supernatant containing retroviral particles was ready for transduction. Donor P14 splenocytes were activated in vitro by 0.1 mg ml−1 GP33 and 10 U ml−1 IL-2 at 37 °C for 24 h, then spin-transduced (1,500g) with fresh retrovirus supernatant from 293T cells for 90 min at 30 °C in the presence of 5 μg ml−1 polybrene.

CRISPR–Cas9/RNP nucleofection

Naive CD8+ T cells were enriched from spleen using the EasySep Mouse CD8+ T cell Isolation Kit (Stemcell Technologies). sgRNAs targeting Zscan20, Jdp2, Etv5, Prdm1 and Hic1 genes or the mouse or human genome non-targeting scramble (control) were obtained from Synthego, Integrated DNA technologies (IDT) and GeneScript (Supplementary Table 5). Cas9 RNP was prepared immediately before experiments by incubating 1 µl sgRNA (stock, 3 nmol in 10 µl water), 0.6 µl Cas9 nuclease (IDT; stock, 62 µM) and 3.4 µl RNase-free water at room temperature for 10 min. Nucleofection of naive CD8+ T cells was performed using a Lonza P3 primary cell kit and program DN100 with 4D-Nucleofector (Lonza Bioscience) for mouse and EO115 for human stimulated T cells. Each nucleofection reaction consisted of approximately 5–10 × 106 cells in 20 µl of nucleofection reagent and mixed with 5 µl of RNP:Cas9 complex. After electroporation, 100 µl of T cell culture medium was added to the well to transfer the cells to 1.5 ml Eppendorf tubes. The cells were rested at 37 °C for 3 min. For in vivo adoptive transfer, cells were resuspended in PBS at the desired concentration and transferred adoptively into recipient mice.

CRISPR gene editing validation by Sanger sequencing

Genomic DNA was isolated from both KO-induced CD8+ T cells and control cells using a Quick-DNA MicroPrep Kit (Zymo). Genomic DNA concentrations were quantified using a NanoDrop One spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific). Following isolation, PCR amplification was performed with 2× Phusion Plus Green PCR Master Mix (ThermoFisher Scientific) and the respective validation primers under the following conditions: 98 °C for 5 min; 35× 98 °C for 10 s, 69 °C for 20 s, 72 °C for 20–30 s kb−1; 72 °C for 2 min; hold at 10 °C). The PCR products were resolved on a 2% agarose gel with SYBR Safe DNA Gel Stain (Invitrogen), and the appropriate bands on the gel were extracted and purified with a Gel DNA Recovery Kit (Zymo). Concentrations of purified amplicon samples were measured and then sent for sequencing with primers designed using Benchling’s Primer3 tool. The samples with KOs were compared with wild-type controls using EditCo’s Ice Analysis software, providing the indel percentages, KO score and the indel distributions used to assess editing efficiency. Indel percent ranged from 56% to 97%, and the KO score throughout experiments ranged from 32 to 74.

Flow cytometry, cell sorting and antibodies

Both single-cell suspensions were incubated with Fc receptor-blocking anti-CD16/32 (BioLegend) on ice for 10 min before staining. Cell suspensions were first stained with Red Dead Cell Stain Kit (ThermoFisher) for 10 min on ice. Surface proteins were then stained in FACS buffer (PBS containing 2% FBS and 0.1% sodium azide) for 30 min at 4 °C. To detect cytokine production ex vivo, cell suspensions were resuspended in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS, stimulated by 50 ng ml−1 phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate and 3 μM ionomycin in the presence 2.5 μg ml−1 Brefeldin A (BioLegend, catalogue no. 420601) for 4 h at 37 °C. Cells were processed for surface marker staining as described above. For intracellular cytokine staining, cells were fixed in BD Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD, catalogue no. 554714) for 30 min at 4 °C, then washed with 1× permeabilization buffer (Invitrogen, catalogue no. 00-8333-56). For transcription factor staining, cells were fixed in FOXP3/transcription factor fixation/permeabilization buffer (Invitrogen, catalogue no. 00-5521-00) for 30 min at 4 °C, then washed with 1× permeabilization buffer. Cells were then stained with intracellular antibodies for 30 min at 4 °C. Samples were processed on an LSR-II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and data were analysed with FlowJo v.10 (TreeStar). Cells were sorted either on a FACSAria III sorter or a Fusion sorter (BD Biosciences). The following antibodies (clone nos.) against mouse proteins were used: anti-CD8a (53-6.7), anti-PD1 (29F.1A12), anti-CX3CR1 (SA011F11), anti-SLAMF6 (13G3), anti-CD38 (90), anti-CD39 (24DMS1), anti-CD101 (Moushi101), anti-KRLG1 (2F1), anti-CD69 (H1.2F3), anti-CD103 (M290), anti-CD62L (MEL-14), anti-TIM3 (RMT3-23), anti-Ly5.1 (A20), anti-Ly5.2 (104), anti-IFNγ (XMG1.2) and anti-TNF (MP6-XT22). The following antibodies (clone nos.) against human proteins were used: anti-CD8a (RPA-T8), anti-CD4 (SK3), anti-CD45RA (H100), anti-CD45RO (UCHL1), anti-CCR7 (G043H7), anti-CD62L (DREG-56), anti-CD69 (FN50), anti-CD103 (Ber-ACT8), anti-CXCR6 (K041E5), anti-PD1 (EH12.2H7), anti-CD38 (HIT2), anti-CD39 (A1), anti-LAG3 (11C3C65), anti-TIM3 (F38-2E2), anti-TIGIT (A15153G), anti-IFNγ (4S.B3), anti-TNF (MAb11), anti-IL-2 (JES6-5H4), anti-GZMB (QA16A02) and anti-G4S Linker (E7O2V). Antibodies were purchased from Invitrogen, Biolegend, Cell Signaling or eBiosciences.

In vivo individual TF KO phenotyping

To assess the functional impact of individual TF gene KOs in CD8+ T cells, we used Cas9-expressing P14 donor cells (LCMV-specific TCR transgenic mice, CD45.1 congenic) transduced with green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing retroviral vectors encoding individual gRNAs. Transductions were performed on the day of adoptive transfer without previous sorting. Without sorting, transduced donor cells (0.5–1 × 105) were transferred immediately into congenically distinct Cas9-expressing wild-type recipient mice (CD45.2) infected 1 day previously with either LCMV–Clone 13 or LCMV–Armstrong strains. At least day 20 post-infection, spleens from the Clone 13 model and spleens and small intestines from the Armstrong model were collected. Single-cell suspensions were prepared and analysed by flow cytometry. Live, single cells were first gated on CD8+ cells, followed by gating on CD45.1+ P14 donor CD8+ T cells. Successfully transduced (gRNA+) cells were identified by GFP expression, which ranged from 10% to 70% of P14 CD8+ T cells across experiments. Because of variability in the number of GFP+ donor P14 CD8+ T cells obtained from different experiments, all phenotypic analyses were performed in the GFP+(gRNA+)CD45.1+CD8+ population. PD1 positive and negative cells, exhaustion subsets (TEXterm:PD1+SLAMF6−CX3CR1− and TEXprog:PD1+SLAMF6+CX3CR1−, TEXeff:PD1+CX3CR1+) or expression of phenotypic markers was reported as a percentage within the gRNA+(GFP+) P14 CD8+ T cell population to ensure consistency across samples.

Co-transfers of control and TF gene KO/overexpression P14 CD8+ T cells in infection or tumour models

Naive CD8+ T cells were isolated from the spleens and lymph nodes of Cas9-expressing LCMV TCR transgenic (Cas9 P14) or P14 mice using an EasySep Mouse CD8+ T Cell Isolation Kit (STEMCELL Technologies). Purified P14 cells were activated for about 24 h on plates coated with goat anti-hamster IgG (ThermoFisher), followed by 1 μg ml−1 hamster anti-mouse CD3 and 1 μg ml−1 hamster anti-mouse CD28 antibodies (ThermoFisher), in complete T cell medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS (HyClone), 55 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 IU ml−1 penicillin-streptomycin and 1% HEPES). After activation, cells were transduced with retroviruses encoding Klf6 overexpression or gRNAs targeting Hic1 or Zscan20 and cultured with 20 IU ml−1 IL-2, 2.5 ng ml−1 IL-7 and 2.5 ng ml−1 IL-15 (PeproTech). At 48 h post-transduction, reporter expression was confirmed by flow cytometry. Donor cell mixes were prepared using control versus Klf6-overexpressing cells (Fig. 4) or gScramble versus gHic1/gZscan20 cells (Fig. 5). For LCMV infection studies, 1.5 × 105 transduced P14 CD8+ T cells were transferred into recipient mice, followed by infection with either 2 × 105 PFU LCMV–Armstrong (acute infection, intraperitoneal) or 2 × 106 PFU LCMV–Clone-13 (persistent infection, intravenous). For tumour studies, 5 × 105 to 1 × 106 transduced T cells (gScramble versus gTF) were transferred on day 7 after B16-GP33 tumour implantation. All experiments were conducted according to guidelines of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Animal Care and Use Committee.

Perturb-seq screening using the retroviral transcriptional factor library

Dual-guide direct-capture retroviral sgRNA vector

To generate a dual-guide sgRNA vector (MSCV-hU6-mU6-SV40-EGFP), we replaced the hU6 RNA scaffold region of the previously described retroviral sgRNA vector MG-guide65 with an additional scaffold66 and the mouse U6 promoter.

Dual-guide direct-capture retroviral library construction

For the curated gene list containing 21 TF genes, a total of four gRNA sequences distributed on two individual constructs were designed for each gene. To construct the library, a customized double-strand DNA fragment pool containing 80 oligonucleotides targeting those 19 TF genes and four scramble gRNAs (each oligonucleotide contains two guides targeting the same gene) (Supplementary Table 5) was ordered from IDT. The dual-guide library was generated using an In-Fusion (Takara) reaction. In brief, the gRNA containing DNA fragment pool was combined in MG-guide vector linearized with BpiI (ThermoFisher). The construct was then transformed into Stellar competent cells (Takara) and amplified, and the resulting intermediate, individual, construct was assessed for quality using Sanger sequencing. Individual dual-gRNA vectors were then combined. For quality control, sgRNA skewing was measured using the MAGeCKFlute67 to monitor how closely sgRNAs are represented in a library.

In vivo screening

Retrovirus was generated by co-transfecting HEK293 cells with the dual-guide, direct-capture retroviral TF library and the packaging plasmid pCL-Eco. Supernatants were collected at 48 h and 72 h post-transfection then stored at −80 °C. Cas9-expressing P14 CD8+ T cells were transduced with the viral supernatant to achieve a transduction efficiency of 20–30%. To ensure sufficient representation of control cells in downstream analysis, 50% of the viral mixture consisted of retrovirus encoding a non-targeting control gRNA vector. For in vivo experiments, 5 × 104 transduced P14 cells were transferred intravenously into Cas9-expressing, puromycin-resistant C57BL/6 recipient mice infected 1 day previously with either LCMV–Clone-13 or LCMV–Armstrong strain. A total of 25 LCMV–Clone-13-infected mice were used for five biological replicates and ten LCMV–Armstrong-infected mice were used for three biological replicates. Each biological replicate was labelled using hashtag antibodies (BioLegend, TotalSeq-C) to enable sample demultiplexing and statistical analysis. At least 18 days post-infection, donor-derived P14 CD8+ T cells were sorted and pooled for Perturb-seq analysis. Preliminary tests indicated that T cells expressing gRNA in vivo exhibit a greater tendency for gRNA silencing over extended periods compared with ex vivo cultured cells, despite initial successful KOs. To mitigate gRNA barcode silencing, we collected tissue between days 18 and 23. Sorted EGFP+ P14 CD8+ T cells were resuspended and diluted in 10% FBS RPMI at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells ml−1. Both the gene expression library and the CRISPR screening library were prepared using a Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 5′ kit with Feature Barcode technology for CRISPR Screening (10x Genomics). In brief, the single-cell suspensions were loaded onto the Chromium Controller according to their respective cell counts to generate 10,000 single-cell gel beads in emulsion per sample. Each sample was loaded into four separate channels. Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 5′ Kit v.2 (catalogue no. 1000263), Chromium 5′ Feature Barcode Kit (catalogue no. 1000541), 5′ CRISPR Kit (catalogue no. 1000451), Chromium Next GEM Chip K Single Cell Kit (catalogue no. 1000287), Dual Index Kit TT Set A (catalogue no. 1000215), Dual Index Kit TN Set A (catalogue no. 1000250) (10x Genomics) in total were used for each reaction. The resulting libraries were quantified and quality checked using TapeStation (Agilent). Samples were diluted and loaded onto a NovaSeq (Illumina) using a 100 cycle kit to obtain a minimum of 20,000 paired-end reads (26 × 91 bp) per cell for the gene expression library and 5,000 paired-end reads per cell for the CRISPR screening library, yielding an average of 42,639; 36,739 and 53,413 reads aligned from cells from in vivo LCMV–Clone-13, in vivo LCMV–Armstrong infection and in vitro donor respectively.

Data analysis

Alignments and count aggregation of gene expression and sgRNA reads were completed using Cell Ranger (v.7.0.1). Gene expression and sgRNA reads were aligned using the Cell Ranger multi count command with default settings. Gene expression reads were aligned to the mouse genome (mm10 from ENSEMBL GRCm38 loaded from 10x Genomics). The median average of four, two and 33 unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) were detected from cells from in vivo LCMV–Clone 13 and LCMV–Armstrong infection, and in vitro donor, respectively. Droplets with sgRNA UMI passing of default Cell Ranger CRISPR analysis Protospacer UMI threshold were used in further analysis. The filtered feature matrices were imported into Seurat68 (v.4.3.0) to create assays for a Seurat object containing both gene expression and CRISPR guide capture matrices. Cells detected with sgRNAs targeting two or more genes were then removed to avoid interference from multi-sgRNA-transduced cells. Low-quality cells with fewer than 200 detected genes, more than 10% mitochondrial reads and less than 5% ribosomal reads were discarded. A total of 17,257 cells (Clone-13) and 15,211 cells (Armstrong) were passed through quality filtering and were used for downstream analysis. Count data were normalized by a global-scaling normalization method and linear transformed69. Cluster-specific genes were identified using the FindAllMarkers function of Seurat. We used Nebulosa70 to recover signals from sparse features in single-cell data and made gRNA density plots with scCustomize71 based on kernel density estimation. In each biological replicate (Clone-13, n = 5; Armstrong, n = 3), the percentage cluster distribution of cells with each TF gRNA vector was calculated. Among two gRNA vectors per target TF, the gRNA vector with higher TEXterm reduction was shown in Fig. 3d and used for Perturb-seq in LCMV–Armstrong infection (Supplementary Table 5). Two-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD test was performed to determine statistical significance. Differentially expressed genes were identified using the MAST model72; the results were then used as inputs for GSEA to evaluate the effect on selected pathways. Genes with P value < 0.05 were considered as differentially expressed genes.

UMAP plots were generated by calculating UMAP embeddings using Seurat and then plotting them as scatter plots using ggplot2. Kernel density calculations for each gRNA were performed on UMAP embeddings using the MASS package using the kde2d function. The kernel density results were plotted as a raster layer with ggplot2 over the UMAP scatter plots. Finally, density contour lines were added using ggplot2’s built-in two-dimensional kernel density contour geom (geom_density_2d).

ATAC-seq library preparation and sequencing

ATAC-seq was performed as described previously73. In brief, 5,000–50,000 viable cells were washed with cold PBS, collected by centrifugation, then lysed in resuspension buffer (RSB) (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2) supplemented with 0.1% NP40, 0.1% Tween-20 and 0.01% digitonin. Samples were incubated on ice for 3 min, then washed out with 1 ml RSB containing 0.1% Tween-20. Nuclei were pelleted by centrifugation at 500g for 10 min at 4 °C then resuspended in 50 μl transposition mix (25 μl 2× TD buffer, 2.5 μl transposase (100 nM final), 16.5 μl PBS, 0.5 μl 1% digitonin, 0.5 μl 10% Tween-20, 5 μl H2O) and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min in a thermomixer with 1,000 rpm mixing. DNA was purified using a Qiagen MinElute PCR cleanup kit, then amplified by PCR using indexed oligos. The optimal number of amplification cycles for each sample was determined by quantitative PCR. Libraries were size-selected using AmpureXP beads and sequenced using an Illumina NextSeq500 for 75-bp paired-end reads.

ATAC-seq analysis

Paired-end 42-bp or paired-end 75-bp reads were aligned to the Mus musculus mm10 genome using Burrow–Wheeler aligner74,75 with parameters ‘bwa mem -M -k 32’. ATAC-seq peaks were called using the MACS2 (ref. 76) program using parameters ‘callpeaks -qvalue 5.0e-2 –shift -100 –extsize 200’. Differentially accessible regions were identified using DESeq2 (ref. 77). Batch effect was removed using limma78. Heatmap visualization of ATAC-seq data was performed using pheatmap.

scRNA-seq metadata analysis

Analysis was performed primarily in R (v.3.6.1) using the package Seurat68,79 (v.3.1), with the package tidyverse80 (v.1.2.1) used to organize data and the package ggplot2 (v.3.2.1) to generate figures. scRNA-seq data from GSE10898, GSE99254, GSE98638, GSE199565 and GSE181785 were filtered to keep cells with a low percentage of mitochondrial genes in the transcriptome (less than 5%) and between 200 and 3,000 unique genes to exclude poor quality reads and doublets. Cell cycle scores were regressed when scaling gene expression values and TCR genes were regressed during the clustering process, which was performed with the Louvain algorithm within Seurat and visualized with UMAP. To quantify the gene expression patterns, we used Seurat’s module score feature to score each cluster based on its per cell expression of TFs.

To obtain Extended Data Fig. 5a, raw single-cell count data and cell annotation data were downloaded from NCBI GEO44 (GSE99254). Count data were normalized and transformed by derivation of the residuals from a regularized negative binomial regression model for each gene (SCT normalization method in Seurat68, v.4.1.1), with 5,000 variable features retained for downstream dimensionality reduction techniques. Integration of data was performed on the patient level with Canonical Correlation Analysis as the dimension reduction technique81. PCA and UMAP dimension reduction were performed, with the first 50 principal components used in UMAP generation. Cells were clustered using the Louvain algorithm with multi-level refinement. The data was subset to CD8+ T cells, which were identified using the labels provided by Guo et al.65. Cell type labels were confirmed by (1) SingleR82 (v.1.8.1) annotation using the ImmGen83 database obtained through celda (v.1.10), (2) cluster marker identification and (3) cell type annotation with the ProjecTILs T cell atlas7 (v.2.2.1). After sub-setting to CD8+ T cells, cells were again normalized using SCT normalization, with 3,000 variable features retained for dimension reduction. Owing to the low number of cells on the per-patient level, HArmstrongony84 (v.1.0) rather than Seurat was used to integrate data at the patient level. PCA and UMAP dimensionality reduction were performed as above.

Statistical analyses

Statistical tests for flow cytometry data were performed using Graphpad Prism v.10. P values were calculated using either two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-tests, one-way ANOVA or two-way ANOVA as indicated in each figure. Linear regressions were performed using the ordinary least squares method in R (v.3.6.1). All data were presented as the mean ± s.e.m. P values were represented as follows: ****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.