A flowchart describing the analyses, steps and number of samples used in each individual section can be found in Supplementary Fig. 5.

Patient recruitment and sample collection

The protocol for sample collection was approved by the Mexican National Cancer Institute’s (Instituto Nacional de Cancerología, INCan, México) Ethics and Research committees (017/041/PBI;CEI/1209/17) and the United Kingdom’s National Health Service (18/EE/00076). Patient samples collected for the Utah cohort analysis were derived as described previously47.

Recruitment of patients and sample collection took place from 2017 to 2019. Patients attending follow-up appointments at INCan who had previously been diagnosed with acral melanoma were offered the chance to participate in this study and, upon signing a written consent form, were asked to provide access to a FFPE sample of their tumour tissue that had been kept at the INCan tumour bank, as well as a saliva or normal adjacent tissue sample. Patients provided samples and their clinical data in Excel format with written informed consent. FFPE samples underwent inspection by a medical pathologist to establish whether sufficient tumour tissue was available for exome sequencing. Saliva samples were collected using the oragene DNA kit (DNAGenotek, catalogue no. OG-500).

DNA and RNA extraction

DNA extraction from all saliva samples was performed at the International Laboratory for Human Genome Research from the National Autonomous University of México (LIIGH-UNAM) using the reagent prepITL2P (DNAGenotek, catalogue no. PT-L2P) and the All-Prep DNA/RNA/miRNA Universal Kit (Qiagen, catalogue no. 80224). DNA and RNA extraction from FFPE samples was performed at the Wellcome Sanger Institute (UK) using the All-prep DNA/RNA FFPE Qiagen kit. Samples with >0.1 ng μl−1 were sequenced through the Sanger Institute’s standard pipeline. Saliva and adjacent tissue samples were used for whole-exome sequencing, and only saliva samples were used for genotyping.

Genotyping

Genotyping was performed using Illumina’s Infinium Multi-Ethnic AMR/AFR-8 v.1.0 array at King’s College London and Infinium Global Screening Array v.3.0 at University College London. Sufficient germline DNA was available for genotyping for 80 out of 92 samples (86.9%). Ancestry estimation was performed using PLINK v.1.9, and ADMIXTURE48 v.1.3.0 for unsupervised analysis together with the superpopulations of the 1000 Genomes dataset49. Five superpopulations were identified, corresponding to AFR (Q1), AMR (Q2), SAS (Q3), EAS (Q4) and EUR (Q5) (Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1).

Exome sequencing and data quality control

FFPE samples, saliva and normal adjacent tissue underwent whole-exome sequencing as follows: Exome capture was performed using Agilent SureSelect AllExon v.5 probes and paired-end sequencing was performed at the Wellcome Sanger Institute (UK) in Illumina HiSeq 4000 machines. Control and tumour samples were sequenced to a mean coverage of 43.72×. Alignment was done using BWA-mem50 v.0.7.17, using the GRCh38 reference genome. Sequencing quality filters were performed using Samtools v.1.9 stats51 and fastqc v.0.11.3 (ref. 52). Sample contamination was estimated using the GATK v.4.2.3.0 tool CalculateContamination53. Concordance between sample pairs was estimated using the Conpair v.0.2 tool54. Samples that had less than 90% similarity with their pair (tumour-normal) or showed a level of contamination above 5% were excluded from the study. After this step, 123 samples remained for further analysis.

Somatic SNV calling and identification of driver genes and mutations

The nature of our samples (FFPE) may introduce artefacts that affect our ability to identify SNVs and indels accurately. Therefore, to mitigate this risk and increase specificity, we used three different variant calling tools, albeit at the cost of reduced sensitivity. As formalin fixation can generate DNA fragmentation, this may also affect copy number estimation analyses and, consequently, copy number mutational signature analysis. To mitigate this, we stringently filtered the samples used for this analysis, which affected our statistical power due to a reduced sample size.

Somatic variant calling was done using three different tools (cgpCaVEMan55 v.1.15.2, Mutect2 (ref. 56) v.4.1.0.0 and Varscan2 (ref. 57) v.2.3.9), keeping only the variants identified by a minimum of two out of the three tools. SmartPhase v.1.2.1 (ref. 58) was used for variant pairs phasing. VCF handling was done using bcftools v.1.9 (ref. 59). For BRAFV600E mutations, we kept these variants even if they were identified by only one of the tools as its oncogenicity and relevance in melanoma is well known. When available within the variant calling tool, strand bias filters were applied. A minimum base quality score of 30 on the Phred scale was used. Indel calling was performed using cgpPindel60,61 v.1.15.2. When selecting one sample per patient, preference was given to primaries, and metastases or recurrences were chosen only when a primary had not been collected.

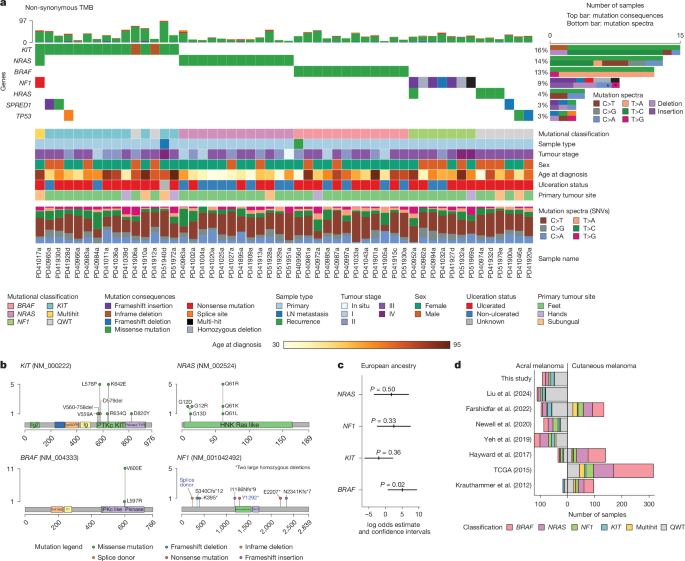

Significantly mutated genes were identified using the tool dNdScv62 v.0.0.1.0 with default parameters using SNVs identified by two of the three tools used for variant calling and indels identified by pindel as input data. Positive selection was considered for genes that had global Q values below 0.1 according to the dNdScv tool recommendations. Visualization of variants was done using Maftools v.2.2.10 (ref. 63).

Two lymph node metastasis samples (one from a patient that had a BRAFV600E mutation and another one with an NRAS mutation) and their primaries were annotated as having the same mutation for follow-up analysis after manual inspection using IGV64.

Analysis of correlation between driver mutations and clinical covariates and ancestry

Statistical tests were performed to identify potential clinical and ancestry covariates that correlated with driver mutational status. For tumour stage, sex, ulceration status and tumour site, which are discrete variables, association was tested with contingency Chi-squared tests.

For each of the four driver genes, a logistic regression model was fitted to predict the presence or absence of a mutation on the acral melanoma samples using the inferred ADMIXTURE48 cluster related to the European ancestry component from the 1000 Genomes Project, correcting for age, sex and total TMB (total TMB, SNVs + indels), as such: driver gene status ~ EUR related cluster proportion + age + sex + total TMB. The log odds related to the EUR cluster were then plotted with their respective confidence intervals. The models were constructed using 80 samples out of the 92, which were those with available genotyping information and with all tested covariables available.

Somatic DNA copy number calling

Sequenza65 v.3.0.0 and ASCAT66 v.3.1.2 were used to estimate ploidy and purity values for each sample. These values per sample were compared between the two tools, and samples that had a high discrepancy in their purity estimates (less than 0.15 versus 1, respectively) were filtered out (Supplementary Table 28). Samples with an estimated goodness of fit below 95 were also filtered out. Subsequently, copy number, cellularity and ploidy values estimated by ASCAT were used in follow-up analyses. Whole genome duplication events were assigned as reported by ASCAT. Regions significantly affected by CNAs were identified using GISTIC2 (ref. 67) v.2.0.23. Amplifications were classified as low-level amplifications when regions had a copy number gain above 0.25 and below 0.9, and as high-level amplifications when regions had a copy number gain above 0.9 according to GISTIC2 values; deletions were classified as low-level deletions when regions had a copy number change between −0.25 and −1.3 and as high-level deletions when regions had a copy number change lower than −1.3. Only peaks with residual Q values < 0.1 were considered as significantly altered. For the analyses of differences in CNA burden by sample group (mutational status or site of presentation), we used the CNApp tool68 to generate GCS, focal copy number alteration scores and broad copy number alteration scores, calculating segment means (seg.mean) as log2(cn/ploidy) and using default parameters. GCS is a number quantifying the copy number aberration level in each sample provided by the CNApp tool68. Higher GCS scores indicate a higher burden of copy number aberrations compared with all other samples in the cohort. GCS is the sum of the normalized broad copy number alteration score and focal copy number alteration score, which are calculated considering broad (chromosome and arm-level) and focal (weighted focal CNAs corrected by the amplitude and length of the segment) aberrations per sample. These values are calculated using as input the number of DNA copies normalized by sample ploidy. A more detailed explanation can be found in the original publication68. GCS values were used for comparisons between sample groups. All paired comparisons between groups were evaluated with a Mann–Whitney test.

To further scrutinise the presence of deletions in tumour suppressors NF1 and CDKN2A, we used CNVkit69 v.0.9.10. We called copy number alterations against a pooled reference generated from the highest quality normal samples, and generated bin-level and segmented level log2 ratios. We calculated the log2 ratio estimated for homozygous deletions for each sample based on ASCAT’s estimation of ploidy and purity as published previously25. For NF1—a large gene—we considered homozygous focal deletions when at least two contiguous bins had log2 ratios at or below the calculated threshold for that sample, or at least one full exon has read coverage equal to zero. For CDKN2A—a small gene—we considered a sample as having a homozygous deletion if it had at least one bin below the threshold, at least two other bins close to the threshold and a noticeable difference in log2 ratios for bins falling in CDKN2A in comparison with its neighbours by manual scrutiny.

Mutational signature analysis

Mutational matrices were generated using SigProfilerMatrixGenerator70 v.1.2.20. These matrices, with single nucleotide mutations found by at least two of the three variant callers and all insertions and deletions identified by cgpPindel, were used as input for mutational signature extraction using SigProfilerExtractor71 v.1.1.23 and decomposition to COSMICv.3.4 (ref. 72) reference mutational signatures72. For single base substitutions, the standard SBS-96 mutational context was used, with default parameters and a minimum and maximum number of output signatures being set as one and five, respectively. A total of 116 samples with an SNV count > 0, were used for this analysis. For copy number signature analysis, all 60 samples with available copy number data were used with default parameters, and using the standard CN-48 context from COSMICv.3.4.

RNA sequencing and data quality control

Total RNA library preparation followed by exome capture using Agilent SureSelect AllExon v.5 was performed on Illumina HiSeq 4000 machines. Reads were aligned to the GRCh38 reference genome using the splice-aware aligner STAR73 v.2.5.0. Of these, we focused on the 77 samples that came from different patients, that had matching DNA and were primaries for the score analysis (see below). We then applied further quality control filters for the consensus clustering analysis: samples were excluded if total read counts were fewer than 25 million, or if the sum of ambiguous reads and no feature counts was greater than the sum of all gene read pair counts. Forty-four samples remained for downstream analysis. Counts were generated with HTSeq74 v.0.7.2. Transcripts per million normalization was performed and values were log2(transcripts per million + 1) transformed.

Acral versus non-acral cutaneous tumour score

Patient samples collected for the Utah cohort analysis were derived as described previously47. Invasive acral and non-acral cutaneous melanomas were identified and collected as part of the University of Utah IRB umbrella protocol no. 76927, Project no. 60, and RNA was extracted and quantified as described previously47. A custom NanoString nCounter XT CodeSet (NanoString Technologies) was designed to include genes differentially expressed between glabrous and non-glabrous melanocytes43,44. Sample hybridization and processing were performed in the Molecular Diagnostics core facility at Huntsman Cancer Institute. Data were collected using the nCounter Digital Analyzer. Raw NanoString counts were normalized using the nSolver Analysis Software (NanoString Technologies). Normalization was carried out using the geometric mean of housekeeping genes included in the panel (Supplementary Table 16). Background thresholding was performed using a threshold count value of 20. Fold change estimation was calculated by partitioning by acral versus cutaneous melanoma. The log2 normalized gene expression data were subjected to principal component analysis (PCA) using the PCA function in Prism v.10.2.1 (GraphPad Software). PCA was performed to identify the main sources of variability in the data and to distinguish between acral and cutaneous samples.

To determine the top differentially expressed genes contributing to the variance between acral melanomas and cutaneous melanomas, the loadings of the second principal component (PC2) were examined. Genes with the highest positive and negative loadings on PC2 were selected as the top ten and bottom ten genes, respectively; log2 expression values of these genes were used to generate a multiplicative score, producing the ratio of acral to cutaneous melanocyte genes. Statistical analyses were performed using Prism v.10.2.1 (GraphPad Software). Differences in acral to cutaneous ratios were assessed using the Mann–Whitney U test.

The acral:cutaneous (A:C) ratio was calculated for each of the 77 primary acral tumours using the method described above after batch correction (limma v.3.64.1, ref. 75) on normalized and transformed expression data processed by the R package DESeq2 v.1.48.1 (ref. 76). Differences in the A:C gene expression ratio scores between BRAF-activating mutation-positive and BRAF-wild-type acral melanoma samples were assessed using a Mann–Whitney U test. The same normalization, scoring method and statistical testing was applied to the 63 transcriptomes from acral melanoma tumours considering BRAF-activating (n = 10) and wild type (n = 53) in Newell et al.15. All available samples in this cohort were used, as only one primary had a BRAF mutation. Only samples with BRAF-activating mutations (V600E and L597R for the Mexican acral melanoma set) were included in the BRAF group.

To determine whether the cutaneous melanoma classifier genes are induced by BRAFV600E signalling in melanocytes, we analysed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data from McNeal et al.40, which consisted of bulk-RNA-seq of primary human melanocytes transduced with BRAFV600E and cultured under two conditions: phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and endothelin-1 (ET1). We extracted normalized expression values for cutaneous melanoma classifier genes across four conditions: PMA, PMA + BRAFV600E, ET1 and ET1 + BRAFV600E. Normalized expression levels were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test in Prism v.10.2.1 (GraphPad Software).

We evaluated the A:C classifier in clinical melanoma samples using RNA-seq data from TCGA Skin Cutaneous Melanoma Firehose Legacy cohort. Normalized gene expression data were downloaded from cBioPortal77. Samples were classified as BRAF-activating or BRAF-wild type in the same way as for Fig. 3c. We calculated the product of the expression of cutaneous melanoma classifier genes for each category. Differences were assessed using the Mann–Whitney U test.

We used an interactive Shiny application, What Is My Melanocytic Signature (WIMMS; https://wimms.tanlab.org)41 to compare transcriptional programs associated with distinct melanocytic cell states. WIMMS classifies melanocytic gene expression profiles by aggregating previously published gene expression signatures and clusters them into seven principal cell state categories. We input our gene signature into WIMMS to assess correlation with these reference states. The resulting dendrogram (Extended Data Fig. 6b) represents the relationship between our classifier-derived cutaneous melanoma genes and known signatures.

Consensus clustering and deconvolution based on gene expression

To identify molecular subgroups based on transcriptome data, we performed consensus clustering using the Cola R v.2.10.1 package78. Standard preprocessing of the input matrix was performed, including removal of rows in which more than 25% of the samples had ‘NA’ (not available) values, imputation of missing values, replacement of values higher than the 95th percentile or less than 5th by corresponding percentiles, removal of rows with zero variance and removal of rows with variance less than the 5th percentile of all row variances. Consensus clustering was performed using several algorithms (k-means, partitioning around medoids, hierarchical clustering) and feature selection methods (s.d., median absolute deviation, coefficient of variation) to ensure robust partition identification. The optimal number of clusters was determined using several stability metrics including 1-PAC (Proportion of Ambiguous Clustering) score, concordance and index, Jaccard index, coefficient and visual inspection of the consensus matrix through heatmaps visualizations. The best-performing method (s.d.:partitioning around medoids with k = 3) was selected based on highest consensus scores and biological interpretability.

Two-level signature analysis

Following sample clustering, we performed a two-level signature analysis to characterize both sample clusters and gene co-expression modules.

Sample cluster characterization

Characterization of sample clusters was performed by identifying genes with significantly different expression across the three identified sample groups using F-tests with false discovery rate correction (P < 0.05). For each differentially expressed gene, we determined the sample cluster with highest mean expression to characterize the molecular profiles of patient subgroups.

Gene module identification

To understand co-expression patterns within signature genes, we applied k-means clustering (k = 3) to group signature genes based on their scaled expression profiles across the three sample clusters. This identified gene modules (M1, M2, M3) representing distinct biological programs that may be co-ordinately regulated across different sample subtypes (Supplementary Tables 17–20).

Functional enrichment analysis

Functional enrichment was performed separately for each gene module using over-representation analysis with the clusterProfiler R package v.4.12.6 (ref. 79). Gene Ontology Biological Process terms were tested using the hypergeometric test with Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate correction (Q < 0.05). Ensembl gene identifiers were mapped to gene symbols using the org.Hs.eg.db v.3.19.1 (ref. 80) annotation package before enrichment analysis (Supplementary Tables 17–20).

The EPIC algorithm81 v.1.1.7 was used in the R programming environment to perform deconvolution to infer immune and stromal cell fractions within acral melanoma tumours. We used the TRef signature method with default parameters, which includes gene expression reference profiles from tumour-infiltrating cells. The algorithm generated an absolute score that could be interpreted as a cell fraction.

Survival analyses

Consenting and recruitment of patients started in 2017 and ended in 2019. Because of the challenges of recruiting sufficient numbers of participants with acral melanoma, patients diagnosed in earlier years who were still attending follow-up clinics for primary or recurrent disease were recruited. To ensue data consistency, only participants with a primary available for analysis were the subject of focus on analyses of recurrence and/or death (n = 85 patients). In total, 73 participants were recruited whose primary and ancestry data were available for analysis on driver mutations. A total of 44 patients with primary and RNA cluster data available were used for analysis on clusters regardless of their ancestry data availability. Analyses were performed with Stata v.19.5 (ref. 82).

To compare the effect of distinct driver mutations and the RNA clusters, we examined two measures of disease severity: (1) the recurrence of the primary tumour and (2) overall survival. For recurrence, we examined time to recurrence using a life-table approach from date of primary diagnosis onwards as a descriptor, and based analyses of differences between mutations (and clusters) on logistical regression adjusting for date of diagnosis, age at diagnosis, sex, stage at diagnosis (advanced/early), ancestry (only for mutations) and time from diagnosis through either death or last known to be alive. Primary tumours were either classified as QWT or mutated for known drivers; tumours with several driver mutations were classified as ‘multi-hit’. We also conducted analyses based on a binary exposure of ‘QWT’ or ‘Mutated’ tumour based on the existence of one or more mutations in a known driver gene.

For survival analysis, we also included a life-table approach, again as a descriptor, based on time from diagnosis through to date of death or date last known to be alive. Statistical assessment of the effect of each mutation and/or cluster were based on Cox proportional hazard analysis with follow-up starting from date of recruitment through to date of death (or last date alive) adjusting for date of diagnosis, age at diagnosis, sex and ancestry (as a sensitivity analysis). Analysis of combined mutations were also conducted as for the recurrence analysis.

To assess the impact of any biases on our interpretation of the impact of mutations, we restricted attention to the 40 tumours diagnosed since the beginning of 2017, that is, those closest to the time of recruitment. Analysis of survival gave qualitatively and quantitatively similar results to those reported above; in total, 7 of 23 (30.4%) of cases with mutated tumours had died, as opposed to 1 of 17 among cases with QWT tumours (P value = 0.055). In the analysis of recurrence, again results matched with 70.0% of cases with mutated tumours recurring (16 of 23 cases) compared with 17.7% of QWT tumours (3 of 17; P value = 0.001). Results for the RNA clusters were similar to the results quoted above for both survival and recurrence.

Data formatting and handling were performed using Python and R.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.