Radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating of the Mokp individual (UCIAMS210906: 2205 ± 20 BP, 364–197 International Radiocarbon Calibration Curve (2020 version, IntCal20) calibrated years bce) was carried out at the Keck Laboratory, University of California, Irvine, following the methodology described by Librado et al.50.

Sex and age-at-death estimations of the human remains

Age-at-death determination methods rely on a variety of skeletal indicators, including stages of auricular surface for adults51,52, stages of iliac crest or sternal end of the clavicle fusion, measurement of long bones for immature individuals53,54 and dental eruption sequences55,56. Biological sex is on the basis of genetic data, especially the so-called Ry ratio (Y to Y + X sequence coverage)57 (Supplementary Table 1a).

DNA extraction

Samples were processed in the clean laboratory facilities at the Centre for Anthropobiology and Genomics of Toulouse (CAGT), University of Toulouse, or at the Centre for GeoGenetics (CGG), University of Copenhagen, following ancient DNA procedures (Supplementary Information section 2.2).

Bone and tooth samples

After gentle surface abrasion, a portion of the dense part of the bone samples was collected using a diamond wheel (PROXXON or ARGOFILE instruments). For tooth samples, the cementum was isolated as recommended by Damgaard et al.58. The samples were either crushed into smaller fragments using a manual mortar or cutting pliers, or pulverized using a Retsch MM200 instrument and then placed in 5-ml Eppendorf LoBind tubes. DNA was extracted following a silica-column-based method, as described by Librado et al.59, without bleach pretreatment (Supplementary Information section 2.2).

Calculus samples

Calculus samples were isolated, as described by Sabin and Yates60. Samples labelled as ‘Name_C’ in Extended Data Fig. 4a (for example, Eletchei3_C_C_P4) were extracted for DNA following a protocol similar to that used for bones and cementum, except that no 1-h predigestion was performed and the digestion volume was limited to 1 ml. Samples labelled as ‘Name_CE’ (for example, Eletchei3_CE_C_P4) were subjected to an overnight digestion at 50 °C in 555 µl of a buffer consisting of 0.45 M EDTA, 1.8 mg ml−1 of proteinase K and 9 mM dithiothreitol. The supernatant was further purified on a QIAGEN MinElute column and eluted in 40-µl sterile water.

Soft tissue samples

Fragments of soft tissues (lung and muscle) were digested in 1.11 ml of a buffer containing 0.45 M EDTA, 1.8 mg ml−1 of proteinase K and 9 mM dithiothreitol, following an overnight incubation at 50 °C with agitation. After 12 min of centrifugation at 8,000 rpm, the supernatant was collected and purified on a silica column (MinElute; QIAGEN; 40-µl sterile water elution).

USER treatment, DNA library building and indexing

An aliquot of 22.8 µl of each DNA extract was incubated with 7-µl USER Enzyme mix (New England Biolabs) for 3 h at 37 °C to limit the impact of post-mortem cytosine deamination in downstream analyses by removing uracil residues. For a few samples, another DNA extract aliquot was also directly converted into a sequencing library.

Sequencing libraries were constructed from double-stranded DNA molecules by ligation of universal (method by Gamba et al.61, adapted from Meyer and Kircher62) or indexed63 blunt-end adaptors. To determine the optimal number of PCR cycles for amplifying DNA libraries and obtaining sufficient material for Illumina sequencing, quantitative real-time PCR was performed on 20X dilution aliquots of most of the libraries. The libraries were amplified for 5–15 cycles using AccuPrime Pfx DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific), with 3.5–6.5 µl of unamplified DNA library and 0.2 mM of each PCR primer in a total reaction volume of 50 µl. One primer of each pair contained an external 6-bp index, read during the Illumina Indexing Read. To limit the proportion of PCR duplicates, up to six independent amplifications were carried out for most DNA libraries. The PCR products were subsequently purified using either MinElute columns (QIAGEN) or AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter), eluted in 20 µl or 25 µl of elution buffer (EB) supplemented with 0.05% Tween and quantified on TapeStation 2100/4200 or Bioanalyzer instruments (Agilent Technologies) and Qubit HS Assay (Invitrogen).

Sequencing

DNA library pools were sequenced at CAGT on the Illumina MiniSeq instrument; at CGG on Illumina NextSeq, HiSeq2000, HiSeq2500 and HiSeq4000 instruments; or at Centre National de Recherche en Génomique Humaine on the Illumina HiSeq X instrument. The vast majority of the sequencing data consisted of paired-end reads.

Reads preprocessing

The demultiplexed FASTQ paired reads were processed using PALEOMIX64 bam_pipeline (v.1.2). Sequencing adaptors were trimmed (-mm 5) as well as poor-quality end, and paired-end reads were collapsed using AdapterRemoval 2 (v.2.3.1; ref. 65). All the resulting reads and those remaining paired were mapped against the hs37d5 reference genome using Bowtie 2 (ref. 66) with local sensitive mapping parameters. The binary alignment/map (BAM) alignment file was further filtered for alignment size superior or equal to 25 bp and mapping quality superior to 30. PCR duplicates were removed using Picard MarkDuplicates (http://picard.sourceforge.net), and realignment around indels was performed using GATK67. Sequencing statistics, as numbers of sequencing reads, endogenous DNA content and coverage are provided in Supplementary Table 1a,b.

All resulting alignments were merged into a single BAM file before pseudo-haploidization, with one read randomly sampled at positions characterized by one or more alignments. Pseudo-haploid genotypes were called using ANGSD (v.0.930; ref. 68) (htslib: 1.9), skipping positions and/or reads showing base and/or mapping Phred quality scores strictly lower than 30 (–doHaploCall 1 -doCounts 1 -minMapQ 30 -minQ 30 -remove_bads 1 -uniqueOnly 1) and restricting calls for those 1,233,013 SNP positions forming the 1240K panel18.

Post-mortem damage and error rates

DNA fragmentation and nucleotide misincorporation patterns were visualized using mapDamage2 (v.2.0.8; ref. 69), with default parameters on a subset of 100,000 random reads. All damage profiles and base compositions were aligned with expected profiles, with or without USER treatment of DNA extracts70.

Error rates were calculated using ANGSD68 and the methodology used in a previous study71 (Supplementary Information section 2.4). Overall, the global error rates of each individual genome characterized in this study ranged between 0.000262 and 0.002819 substitutions per base on average, mostly inflated through transition misincorporations (Supplementary Table 1b).

Uniparental markers, contamination estimates and ploidy check

A total of 46 women and 61 men were identified on the basis of Ry ratio (Supplementary Table 1a). Mitochondrial haplotypes were called using Haplogrep (v.2.266; ref. 72) after aligning reads against the revised Cambridge Reference Sequence reference mitogenome (GenBank accession no. NC_120920.1) and discarding those shorter than 25 bp, with mapping and base qualities below 30 (Supplementary Information section 2.5). The resulting variant call format file was then processed through Haplogrep72, calculating the best 100 hits. Contamination rates on the basis of mitochondrial data were estimated using schmutzi73 and the same base quality threshold as above. Nuclear contamination rates were estimated for male individuals, following the methodology by Rasmussen et al.74 and implemented in ANGSD68. Transition substitutions and sites covered once or more than 200 times were discarded.

Mitochondrial contamination estimates were assessed within a 0–5% confidence range for all individuals but three (Supplementary Information section 2.5 and Supplementary Table 1a), which were conservatively excluded from those analyses conditioned on archaeological stages. Nuclear contamination estimates were found to be limited (median of 0.24%) and inferior to 0.4% (Supplementary Table 1a). Y-chromosome haplotypes were called using the Yleaf statistical package75 (Supplementary Information section 2.5). The ploidy levels of each individual were checked following the methodology described by Sehnert et al.76 (Supplementary Information section 2.6 and Supplementary Fig. 2_3).

Imputation

We imputed a subset of genomes using GLIMPSE2 (ref. 77) and the 1000G19 panel as reference dataset, following the instructions provided by the developers on the software website. To test for the minimal coverage needed to obtain accurate imputation, we downsampled the data of four high-coverage individuals, imputed the resulting genotypes and then assessed imputation accuracy by measuring the squared Pearson correlation between original and imputed genotypes (Supplementary Information section 2.7). We found that a minimal coverage of 0.35-fold was necessary for imputing genotypes represented at MAF of 5% or higher. A total of 90 Yakut individuals (coverage of 0.35-fold or higher) were then imputed and filtered for MAF of 5% or higher and genotype probability of 0.99 or higher for all downstream analyses. The imputed individuals were combined with the phased 1000G dataset for all downstream analyses, except for those on the basis of fineSTRUCTURE21, which required a liftover to the hg38 positions to include the matrix of phased genotypes released by Bergström et al.78, which included 20 modern Yakut individuals.

Kinship analyses

Relatedness between historical Yakuts was assessed on the basis of the pseudo-haploid data using a combination of three complementary methodologies: READ2 (refs. 79,80), lcMLkin81 and TKGWV2 (ref. 82) (Supplementary Information section 2.8 and Supplementary Table 1r–t). For READ2 (refs. 80,81) and TKGWV2 (ref. 82), the autosomal positions overlapping the 1240K dataset were used, restricting the former to MAF of 1% or higher. We disregarded first-degree and second-degree relationships if estimated from less than 1,000 and 2,000 SNPs, respectively, whereas the default filter of READ2 (refs. 79,80) was used for assessing third-degree relationships. Precise genealogies were reconstructed using the READ2 (refs. 79,80) results, age-at-death estimations, uniparental markers and estimated period of burial of each individual (Extended Data Fig. 5b and Supplementary Information section 2.8).

Identity-by-descent (IBD) contents were calculated using ancIBD83 on the direct output of GLIMPSE2 without MAF and genotype probability filters. As recommended, the Yakut dataset was downsampled to 1,240,000 SNPs, for which ancIBD was optimized, and IBD sharing was screened for every pair of imputed individuals (coverage of 0.35-fold or higher), with default settings83. For population analyses, individuals with the least SNPs covered in each pair of first-degree or second-degree relatives were removed.

Inbreeding and diversity estimates

The effective population sizes for each stage and region were estimated on the 1240K SNP pseudo-haploid panel, restricted to individuals with at least 400,000 SNPs covered, using hapROH26 with default parameters and 5,008 haplotypes from the 1000G project as a reference panel (Supplementary Table 1j). For each archaeological stage, PCA individual outliers were removed.

ROH were identified on the imputed dataset using plink84 (–homozyg) on set of 1000G biallelic transversions with MAF higher than 5%, removing any positions not fully covered (–geno 0). Inbreeding scores were calculated with plink84 (–het) using transversions only and MAF of 5% or higher (Supplementary Information section 2.9 and Supplementary Table 1a). To further confirm our results, we performed ROH detection using hapROH26 on the pseudo-haploid data for individuals with at least 400,000 SNPs covered on the 1240K panel (Supplementary Information section 2.9 and Supplementary Fig. 2_4).

Principal component analysis

PCA was carried out using the Human Origins reference panel for 597,573 autosomal genotypes. Genotypes were downloaded from the Allen Ancient DNA Resource (v.5) website18. We also included the genotypes from those Central Asian individuals with relevant genetic ancestry profiles reported by Zhang et al.85. PCA was on the basis of pseudo-haploid genotype calls for all the individuals presented in this study and carried out using smartPCA from EIGENSOFT (v.7.2.170; ref. 86), projecting 913 ancient Eurasian and American individuals and 106 ancient Yakut individuals (coverage of higher than 0.02-fold) onto the principal components obtained from in 2,761 Eurasian modern individuals (lsqproject, YES; shrinkmode, YES; Supplementary Information section 2.10 and Supplementary Fig. 2_5, where a non-projected PCA is shown). Projections on the first two principal components are provided in Fig. 2a, whereas PC2 and PC3 are provided in Extended Data Fig. 3b. A second PCA was carried out to validate our imputation pipeline by confirming similar projections for imputed genotype data and pseudo-haploid data (Supplementary Information section 2.10 and Supplementary Fig. 2_6).

ADMIXTURE

Unsupervised ADMIXTURE (v.1.3.0; ref. 20) analyses were carried out to estimate the proportions of genetic ancestries present in Yakuts (coverage of 0.03-fold or higher; pseudo-haploid) using autosomal positions as part of the 1240K Human Origins panel and a total of 3,639 Eurasian and American individuals. Sites were thinned for linkage disequilibrium with plink84 (–indep-pairwise 200 25 0.4), resulting in a total of 327,582 SNPs. Confidence intervals were estimated from 100 bootstrap pseudo-replicates. Analyses were repeated ten times using ten random seeds to assess convergence (Supplementary Information section 2.11 and Supplementary Fig. 2_7). Full ancestry profiles are provided in Supplementary Fig. 2_8 for the entire dataset.

FineSTRUCTURE

A fineSTRUCTURE (v.2; ref. 21) analysis was performed on the imputed data to explore patterns of haplotype sharedness. Imputed transversion genotypes were converted to hg38 positions with the tool LiftoverVcf from the Picard Toolkit 2019 (https://github.com/broadinstitute/picard), and related individuals were removed before merging with the phased genotypes from Bergström et al.78. The genotype positions showing missingness in at least one individual were removed, and MAF of 1% or higher was required, resulting in 1,059,615 autosomal sites. The merged dataset was split by chromosome, rephased using SHAPEIT (v.2; ref. 87) and transformed into ChromoPainter (v.2; ref. 21) format using ‘impute2chromopainter.pl’ and a chromosome-based recombination map generated through the ‘makeuniformrecfile.pl’ script. ChromoPainter (v.2; ref. 21) analyses were on the basis of 20 expectation–maximization iterations (-s1emits 20 -in -iM), with a starting switch rate of 250 (-n 250) and a global mutation rate of 0.0005 (-M 0.0005). The fineSTRUCTURE Markov chain Monte Carlo model was run on the ChromoPainter (v.2) output for 3,000,000 burn-in iterations and 2,000,0000 sampling iterations with no thinning (-s3iters 5000000 -s3iterssample 2000000 -s3itersburnin 3000000). The resulting co-ancestry matrix is shown in Extended Data Fig. 3c.

D-statistics

Different combinations of D-statistics were calculated using qpDstat in ADMIXTOOLS (v.5.056; ref. 23) to detect gene flow by testing whether pairs of modern and ancient Yakuts from each archaeological stage were symmetrically related to modern Eurasian populations. Calculations were carried out on the pseudo-haploid 1240K dataset using Mbuti (N = 10; ref. 78) as outgroup. The topologies investigated were in the form of (outgroup, Eurasian modern populations; StageX, StageY/modern Yakut). The results of the different D-statistics calculations, with Z scores corrected for multiple testing (Benjamini–Hochberg), are provided in Extended Data Fig. 3d, permuting StageX and StageY among the four archaeological stages and modern Yakuts. Positive values indicate closer genetic proximity between the modern Eurasian population and StageY (or modern Yakuts), relative to StageX.

Admixture modelling and dating

Admixture models for ancient Yakut individuals (coverage of 0.1-fold or higher) were assessed using the pseudo-haploid 1240K dataset and qpAdm from ADMIXTOOLS (v.5.056; ref. 23), applying the feasibility criteria recommended by Flegontova et al.88, that is, coefficient ± 2 s.e. within the [0, 1] interval (P ≥ 0.01). The qpAdm models were aimed at testing whether the Yakut genomic makeup was compatible with a two-way admixture from a local Siberian background (Yakutia_IA, N = 2, comprising Mokp and yak03041 because they showed similar genetic profiles and PCA placements) and another source, potentially from the Baikal region (Baikal_his (N = 4) or Baikal_sib (N = 11)) or Russia (Russian78) (Supplementary Table 1f). Baikal sources were defined as Baikal_sib (N = 11) and Baikal_his (N = 4). The former included Mongolia_Khuvsgul_LateMedieval89 (N = 2), Mongolia_Dornod_LateMedieval89 (N = 7) and Mongolia_Khentii_LateMedieval89 individuals (N = 2), whereas the latter comprised Russia_AngaraRiver_Medieval.SG22 (N = 1), Mongolia_Sukhbaatar_Xiongnu (N = 1) and Mongolia_Khuvsgul_MLBALateMedieval89 individuals (N = 2). A full range of qpAdm admixture models were tested to identify the best sources for Baikal_his and the best western Russian source, including Yakutia_IA, Russia_AngaraRiver_Medieval.SG22 (N = 1), Mongolia_Sukhbaatar_Xiongnu (N = 1), Mongolia_Khuvsgul_MLBALateMedieval89 individuals (N = 2) and Buryat.SG90,91 (N = 4), and extending western sources to Polish, Bulgarian, Czech in addition to Russian (accounting for Slavic-speaking populations), Adygei, Abkhasian, Chechen, Lezgin and North Ossetian groups (accounting for the North Caucasus), Mansi (to represent Uralian-speaking populations) and Altaian (Turko–Mongolic-speaking populations) (Supplementary Information section 2.12 and Supplementary Table 1g). This resulted in the exclusion of Buryat.SG from the Baikal_his group because almost all of its models failed, whereas the other groups tested yielded consistent results. No other western sources outperformed the Russian group; therefore, we kept it as a proxy for the western source for the final models (Supplementary Information section 2.12 and Supplementary Table 1g). The Baikal_sib populations were selected because they exhibited the closest ADMIXTURE20 ancestry profiles (Supplementary Information section 2.11). Each ancient and modern individual from Yakutia was tested for every combination of two or three populations, putting the non-used population in the right group92 (Supplementary Table 1f).

We further applied DATES24, using both the pseudo-haploid and imputed datasets, to two-way models to estimate the time of the admixture event between the local ancestry source (Yakutia_IA + Nganasan) and Baikal populations (Supplementary Information section 2.12 and Supplementary Table 1h). Because the confidence intervals using the Baikal_sib source were more restrained (Supplementary Table 1h) and Baikal_sib covered more individuals, analyses incorporating the Baikal_sib source were preferred (Fig. 3d). The time of admixture between a Russian source78 and either a historical Yakut ancestry source (Yakut_his, comprising all newly sequenced Yakut individuals from the four stages, excluding related individuals and genetic outliers; N = 92) or the local ancestry source (Nganasan + Yakut_IA; N = 37) was also estimated for the imputed genomes of the PCA genetic outliers (Supplementary Table 1h). The corresponding weighted linkage disequilibrium decay curves are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2_9 and discussed in Supplementary Information section 2.12).

Bottleneck dating

We used ASCEND25 to assess the intensity and estimate the time for the bottleneck underlying the foundation of the Yakut gene pool. These analyses were first run without specifying an outgroup and then repeated by choosing an outgroup (N = 15) randomly from the populations present in our dataset. Analyses were carried out by considering archaeological stages individually or the entire group of ancient Yakuts, both for the pseudo-haploid and imputed datasets, with the following parameters: binsize, 0.001; mindis, 0.001; maxdis, 0.3; maxpropsharingmissing, 1; minmaf, 0; usefft, YES; qbins, 100 (Supplementary Information section 2.13 and Supplementary Table 1i). The allele-sharing correlation decay curve together with the fitted exponential model from our outgroup tests are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2_10 and discussed in Supplementary Information section 2.13).

Microbial profiling

Microbial taxonomic profiles were determined for each individual DNA sample, restricting analyses to the fraction of collapsed reads. Reads aligned to the human genome (hg37) and the human mitochondrial genome were filtered out (Supplementary Information section 2.14). Microbial read counts were obtained using MetaPhlAn4 (ref. 29) (Supplementary Table 1l), discarding unclassified and too short reads. We applied a minimal read length filter set to the most frequent read length value (visually checked) minus ten, with strict boundaries set at less than 30 bp and greater than 70 bp (Supplementary Information section 2.14). This procedure was repeated on a panel of known sources (Supplementary Information section 2.14 and Supplementary Table 1k (for details and references)) that were used to assess the proportion of oral microbes contributing to each ancient DNA library, using SourceTracker2 (ref. 93), conditioning analyses on species level (Extended Data Fig. 4a). Samples showing more than 25% of oral sources were retained for further analyses because such proportions were observed in oral samples previously analysed and identified as authentic48. In cases where both tooth and calculus samples from the same individual passed filters, the profile maximizing oral microbial sources was kept, resulting in a final dataset of 74 individual oral microbiomes.

Bacterial taxa showing abundances lower than 1% were disregarded before carrying out composition visualization (Supplementary Fig. 2_11) and PCoA on the basis of Bray–Curtis distances (Fig. 3a). Species abundances of microbes belonging to different bacterial complexes (red, orange, yellow, green and purple), together with eight known oral pathogens, were measured and tested for potential shifts across archaeological stages (Kruskal–Wallis test; Fig. 3d, Supplementary Information section 2.14 and Supplementary Fig. 2_12). These analyses were repeated on a dataset restricted to calculus samples (Supplementary Information section 2.14 and Supplementary Fig. 2_13).

We also performed two complementary analyses to reveal subtle commonalities in the microbial compositions of the different samples that may have remained undetected in PCoA (Supplementary Information section 2.14). The first analysis followed Quagliariello et al.46 and their network and clustering methodology. No association was found in the distribution of individuals among clusters and archaeological stages (Pearson’s χ2 test; P = 0.92; Supplementary Information section 2.14 and Supplementary Fig. 2_14). The second analysis investigated strain-level variation in the oral pathogens detected using StrainPhlAn4 (refs. 29,94), considering the most abundant bacterial species of the red complex and eight pathogens. Metagenomic data from dental calculus of several individuals, including Neanderthal outgroups and Eurasian individuals who lived within the past 500 years (Supplementary Table 1n), were accessed through the AncientMetagenomeDir (v.24.09; ref. 95) repository. These data were processed similarly to Yakut data before running StrainPhlAn4 with default parameters to extract species-specific MetaPhlAn markers. We prepared multi-FASTA alignments combining those markers together across all individuals and reconstructed maximum likelihood phylogenies in IQ-TREE (v.1.6.12; ref. 96) to assess whether or not new strains arrived in Yakutia at a specific archaeological stage (Supplementary Information section 2.15 and Supplementary Figs. 2_15–2_17). The best substitution model was estimated using the Akaike information criterion (-m MFP), and node support was assessed from 1,000 ultrafast bootstrap97 pseudo-replicates (UFBoot) (each bootstrap tree optimized using a hill-climbing nearest-neighbour interchange search; -bb 1000 -bnni). When the number of Neanderthal hits was found too limited to use them to root, the trees were rooted at midpoint.

The sequence data passing the SourceTracker2 filters described above were also subjected to functional analyses using the methodology implemented in HUMAnN 3.0 (ref. 30), with default parameters (Supplementary Table 1o). This step generated per-individual functional profiles on the basis of the UniRef90 (ref. 31) and ChocoPhlAn (January 2023; ref. 32) databases, which were further joined by pathways, normalized by counts per millions and centred log-ratio transformed to deal with compositional values that may arise from specific normalization in sequencing data, before conducting PCA (Fig. 3b). Selected pathways associated with carbohydrate or amino acid metabolism were scrutinized for their relative abundances across individuals and compared by archaeological stages using a Kruskal–Wallis test (P ≥ 0.067; Fig. 3c, Supplementary Information section 2.16 and Supplementary Fig. 2_18). These analyses were repeated on a dataset restricted to calculus samples (Supplementary Information section 2.16 and Supplementary Fig. 2_19).

Pathogen screening

Reads aligned to the human genome (hg37) and the revised Cambridge Reference Sequence mitochondrial genome were filtered out (Supplementary Information section 2.17). The resulting filtered FASTQ files were used for mapping against a selection of reference genomes from candidate pathogens (N = 26; Supplementary Information section 2.17 and Supplementary Fig. 2_20a). This alignment step was carried out using PALEOMIX64 bam_pipeline (v.1.2) and bwa-0.6 (ref. 98) (backtrack; MinQuality, 30; no seed; -n, 0.1), which produced high-quality BAM alignments that were removed for PCR duplicates. The number of aligned reads against each reference genome was counted per sample, together with average read-to-reference edit distances. We considered a sample positive for the presence of any given pathogen as long as a minimal number of 100 high-quality alignments were identified, and the average edit distance was equal to or below 0.01. This conservative approach resulted in the identification of three individuals positive for Variola major, the aetiologic agent of smallpox (AC1S2, AC1S3 and Rassoloda; Supplementary Information section 2.17 and Supplementary Fig. 2_20b).

Smallpox genome analysis

All the sequence data generated for the three smallpox-positive individuals were realigned against the variola virus (VARV) smallpox reference genome (accession no. NC_001611.1), using the same procedure as above, except that the minimum alignment size was restricted to 30 bp instead of 25 bp to maximize potential sequence coverage. Although positive, AC1S3 did not provide a sufficient number of reads (N = 199) to proceed further with the rest of the analyses (Supplementary Table 1p). We next used mapDamage2 (v.2.0.8; ref. 69) with default parameters, and genotypes were called using bcftools (v.1.17; ref. 99) mpileup and call modules, requiring a maximum depth corresponding to the 99.5th percentile of the depth distribution, minimal base and mapping Phred qualities of 30 and considering the genome haploid. Low-quality genotypes (Phred quality score lower than 30), indels and polymorphisms within two base pairs of an indel were removed using the bcftools (v.1.17; ref. 99) filter.

To place the smallpox strains identified in the smallpox phylogenetic tree, we applied the same procedure as above to the raw reads previously published for five ancient samples36,37. Additionally, the FASTA sequence data corresponding to 45 smallpox genomes from the twentieth century previously characterized were downloaded100,101 (Supplementary Table 1q). The multi-FASTA sequence data, corresponding to the 45 modern viral genome, including the reference genome, were further aligned using MAFFT102 and manually corrected wherever appropriate. Gaps were added to the six ancient samples according to the gaps in the reference genome after the alignment procedure, and all FASTA were merged to form a multi-FASTA sequence of 52 viral genomes. Positions in which at least 50% of the sequences were covered were retained for maximum likelihood reconstruction in IQ-TREE (v.1.6.12; ref. 96) (-m MFP). Node support was estimated from 1,000 ultrafast bootstrap97 pseudo-replicates (-bb 1000 -bnni). A tree was also generated using the same procedure as described above, removing the manual correction of the modern genome alignment (Supplementary Information section 2.18 and Supplementary Fig. 2_21). The position of our sample in the tree obtained was then tested against seven alternative tree conformations by running an approximately unbiased topology test103 (Supplementary Information section 2.18 and Supplementary Fig. 2_22).

Ancient DNA methylation values calibration

We used DamMet104 to evaluate DNA methylation levels in the genomes of 21 individuals with coverage greater than 9-fold, as a previous study established that relatively high coverage thresholds were needed to obtain reliable estimates. Overall, we followed the procedure previously described by Liu et al.105 to identify the best combination of parameters for DamMet104 DNA methylation inference (Supplementary Information section 2.19). The average cellular methylation fraction (M) was found to have no impact on correlation levels (Supplementary Information section 2.19, Supplementary Fig. 2_23 and Supplementary Table 1u); hence, a value of 75% was retained. Maximal correlation levels (0.38–0.8) were otherwise obtained for a maximum window size of 1 kb, windows of 25 CpGs and a minimum depth of 400 reads per window. Four individuals presented low correlation scores (Spearman correlation; R2 < 0.55) and were thus disregarded.

Despite encouraging correlation levels, two DNA methylation categories associated with scores of 0 and 1 were under-represented in the remaining samples (Supplementary Information section 2.19 and Supplementary Fig. 2_24a), in line with the work from Liu et al.105. We therefore followed the mitigation procedure developed by those authors to improve ancient DNA methylation inference using approximately 27.2 million CpGs in two modern bones published by Gokhman et al.106 (Supplementary Information section 2.19 and Supplementary Fig. 2_24b).

The validity of the resulting DNA methylation inference was also assessed by checking for the presence of well-established patterns along the genome (CpG islands, exons and introns and CTCF binding site regions), following the method by Hanghøj et al.107 (Supplementary Information section 2.19 and Supplementary Figs. 2_25–2_27). The DNA methylation profile observed for the Otchugoui individual did not align with expectations for CpG islands, exons and introns and CTCF binding regions, and it was therefore disregarded.

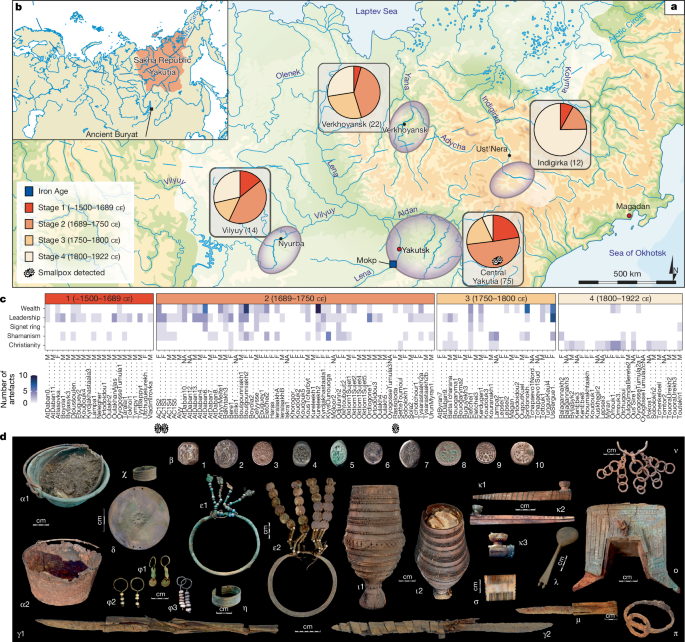

Statistical associations between cultural and non-cultural data

We generated a presence–absence matrix summarizing the characteristics of each burial (Supplementary Information section 2.20 and Supplementary Table 1a) and calculated pairwise Bray–Curtis between individuals (Supplementary Information section 2.20 and Supplementary Fig. 2_28). To test whether the distribution of distances calculated between pairs of individuals within categories (sex, region and archaeological stages) was significantly different from random permutations of individuals across categories, we used ANOSIM (anosim from the vegan package108 in R109) and a permutational multivariate analysis of variance (adonis2 from the vegan package108 in R109) (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table 1v).

Moreover, we binned individuals into four extra categories defining wealth, leadership, Christianity and shamanism on the basis of the collection of cultural goods found in their burials (Supplementary Information section 2.20). To test whether the similarity of the oral microbiome between groups in these categories was lower than the similarity within each group, we used ANOSIM and permutational multivariate analysis of variance (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table 1v). These analyses were repeated for taxonomic and functional distances, genetic distances (ASD) and DNA methylation distances (Bray–Curtis; Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table 1v).

Ethics and inclusion

This study builds upon more than 15 years of archaeological research conducted in Yakutia, Sakha Republic, an autonomous region of the Russian Federation located in northeastern Siberia (Supplementary Information section 1.3). The fieldwork was conducted under the MAFSO programme (French Archeological Mission in Eastern Siberia), a collaboration between French researchers and local Yakut experts, including scholars from North-Eastern Federal University in Yakutsk. The programme was approved in June 2012 by the Local Committee for Biomedical Ethics of the Federal State Budgetary Institution, known as the Yakut Scientific Center of Complex Medical Problems of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences. Throughout the programme, local experts were fully engaged as equal partners, contributing to research design, archaeological excavations, material selection for analysis, community outreach, permit acquisition and critical feedback on analyses and manuscripts. Their contributions are reflected in their co-authorships in this study and 21 scientific articles and reviews published between 2004 and 2021. The research team also implemented a wide array of activities to engage with local communities, including fieldwork and student training, and played an active role in public outreach through documentaries, press interviews, television programs and exhibitions. The programme was supported by several inter-university collaborative research agreements, notably between Université Paul Sabatier, Krasnoyarsk State Medical University and North-Eastern Federal University in Yakutsk. It also received endorsement from the Institute of Ecology and Evolution at CNRS through the International Associated Laboratory ‘Coevolution Human–Environment in Eastern Siberia’. The programme facilitated extensive community engagement, highlighted by the 2019 exhibition at the Historical Park Rossiya-Moya Istoriya in Yakutsk, which showcased the main archaeological discoveries made under MAFSO.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.