Mouse husbandry

Mice were housed in standard conditions on a 12-h light–dark cycle and provided with water and standard chow ad libitum. In some experiments, as documented in the main text, mice were provided with water infused with an azido-amino acid or 0.1% methionine, 0.35% cysteine (low methionine) chow (Envigo, TD.160659). All animal procedures were approved by the Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care at Stanford University. All experiments used male mice. No power analysis was performed to determine sample sizes. Randomization and blinding were not performed and were generally not relevant to the experiments reported herein.

Mouse sources

All transgenic mouse lines were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Besides the BONCAT lines generated in this study, the generation of which is described below, the transgenic lines used in this study included B6.Cg-Tg(Camk2a-cre)T29-1Stl/J (The Jackson Laboratory, 005359), B6.C-Tg(CMV-cre)1Cgn/J (The Jackson Laboratory, 006054), C57BL/6-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(CAG-GFP,-Mars*L274G)Esm/J (The Jackson Laboratory, 028071) and B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm14(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J (The Jackson Laboratory; 007914). Homozygous cre lines were bred to homozygous BONCAT lines or the Ai14 reporter line to generate offspring heterozygous for the cre driver and heterozygous for the BONCAT transgene or Ai14 reporter transgene. Wild-type C57BL/6 mice used for ageing-related AAV transduction experiments were obtained from the National Institute of Aging colony. Wild-type C57BL/6 used for non-ageing-related AAV transduction experiments or used as background controls were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory.

Transgenic mouse generation

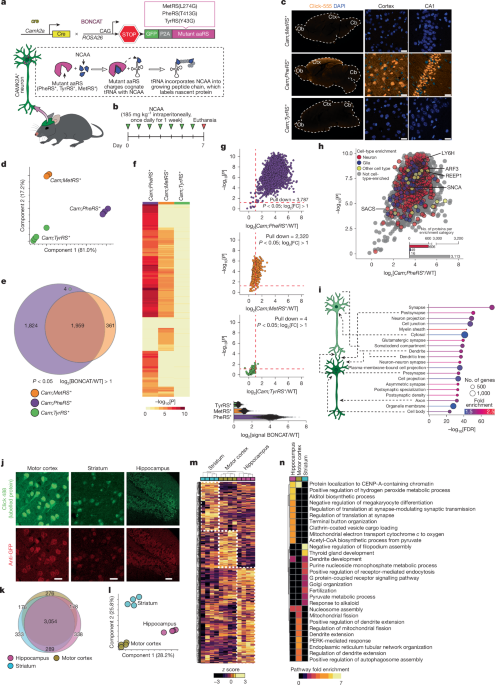

The new BONCAT models, PheRS(T413G) and TyrRS(Y43G), introduced in this paper were generated in collaboration with The Jackson Laboratory. sgRNAs (ACTGGAGTTGCAGATCACGA and GCAGATCACGAGGGAAGAGG) were designed to insert a cassette encoding a CMV-IE enhancer/chicken β-actin/rabbit β-globin hybrid promoter (CAG) followed by a floxed stop cassette containing 3×SV40 polyadenylation signals, an eGFP sequence, a viral 2A oligopeptide (P2A) self-cleaving peptide, which mediates ribosomal skipping, and either the gene encoding PheRS(T413G) or TyrRS(Y43G) into the Gt(ROSA)26Sor locus. gRNA, the cas9 mRNA and a donor plasmid were introduced into the cytoplasm of C57BL/6J-derived fertilized eggs with well-recognized pronuclei. Injected embryos were transferred to pseudopregnant females. Surviving embryos were transferred to pseudopregnant females. Resulting progeny were screened by DNA sequencing to identify correctly targeted pups, which were then bred to C57BL/6J mice for germline transmission. This colony was backcrossed to C57BL/6J mice for at least three generations. Sperm was cryopreserved at The Jackson Laboratory. To establish our live colony, an aliquot of frozen sperm was used to fertilize C57BL/6J oocytes. The PheRS(T413G) model (C57BL/6J-Gt(ROSA)26Sorem2(CAG-GFP,-Farsa*T413G)Msasn/J) and the TyrRS(Y43G) model (C57BL/6J-Gt(ROSA)26Sorem3(CAG-GFP,-Yars1*Y43G)Msasn/J) are available for purchase from The Jackson Laboratory (stocks 033734 and 033735, respectively).

Biological replicates

All mice were maintained as individual biological replicates except for the neuron-to-microglia protein-transfer experiments. In the neuron-to-microglia protein-transfer experiment, enriched labelled neuronal protein from microglia was expected to be relatively minimal. Therefore, to ensure detection by LC–MS, the brains of 3 mice, for a total of 900,000 microglia, were pooled to generate a single biological replicate.

Background controls

Background controls are necessary for all BONCAT studies to account for proteins that are nonspecifically enriched by the DBCO pull-down method or nonspecifically labelled with fluorescent alkynes. Background control mice, wild-type mice genetically incapable of incorporating the NCAA, were treated identically with the NCAA relative to their BONCAT counterparts. In all of our experiments, background controls represent the same biological material (brain region, mouse age, protein fraction and/or cell type) as the labelled sample under analysis. In the protein degradation study, background samples for each labelled age and region were derived from the same respective age and region of background control mice. In the protein aggregation study, background samples for each labelled aged aggregate sample were derived from aggregates isolated from aged background control mice. In the microglia study, background samples for each microglia sample derived from labelled mice were from microglia isolated from background control mice.

Mouse AAV injection

Mice were anaesthetized with isoflurane and 3 × 1011–5 × 1011 AAV genome copies were injected in 100 μl sterile 1× PBS via the retroorbital sinus. Equal genome copies were injected in mice between which comparisons would be made. For maximal transgene expression, mice were used no sooner than 3 weeks following initial transduction.

NCAA preparation and administration

All AzAAs, including 4-azido-l-phenylalanine (Vector Laboratories; 1406-5G), N-epsilon-azido-l-lysine hydrochloride (Iris Biotech, HAA1625.0005) and 3-azido-l-tyrosine (Watanabe Chemical Industries, J00560) were prepared as a 12.35 mg ml–1 solution for intraperitoneal injections. To hasten the dissolution of AzF, it was first dissolved in 1 M NaOH at 111 mg ml–1, after which it was brought to 12.35 mg ml–1 with sterile 1× PBS. Immediately before intraperitoneal injection at 185 mg kg–1, aliquots were brought to a neutral pH by the addition of 1 M HCl. Unless otherwise noted, NCAAs were injected once daily for 7 consecutive days for both BONCAT lines and wild-type background control mice. All data in Fig. 1 were derived from experiments in which the NCAAs were administered by intraperitoneal injections as described above. For all experiments, including the protein degradation experiments, mice were killed approximately 16 h after the final amino acid administration to allow for sufficient incorporation into nascent proteins. Note that labelling occurs during protein synthesis, which is occurring at different periods and rates for different proteins, not all at one instance after amino acid administration. Thus a sufficient amount of time between amino acid administration and sample collection is necessary to achieve sufficient labelling. This could affect half-life determinations, but this is an unavoidable challenge of any protein degradation experiment.

For the experiments in which 4-azido-l-phenylalanine-infused water was given to mice, 4-azido-l-phenylalanine was dissolved in sterile water at 1 mg ml–1. The water was brought back to its original pH by the addition of NaOH. The only experiment to use an AzF water treatment protocol was the neuron-to-microglia protein-transfer experiments. In such experiments, mice also received AzF via intraperitoneal injections as described above. This AzF treatment protocol aimed to enhance neuronal labelling and to increase the likelihood of detecting neuronal proteins in microglia, which we reasoned would be a rare event.

Tissue collection and handling

Mice were anaesthetized with isoflurane and transcardially perfused with at least 20 ml of 1× PBS. After perfusion, brains were immediately extracted and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, snap-frozen in tubes on dry ice or immediately enzymatically dissociated. For experiments requiring brain region dissection, after brain extraction, regions were immediately dissected on ice using a ‘rodent brain matrix’ 1-mm coronal slicer (Tedpella, 15067) according to coordinates obtained from the Mouse Brain Library (http://www.mbl.org/) using the C57BL/6J atlas as a reference. After dissection, regions were snap-frozen in tubes. In cases in which tissue was fixed, tissue was fixed for 24 h and then prepared for either paraffin embedding or sucrose cryoprotection. Snap-frozen tissue was stored long-term at −80 °C.

Isolation of microglia

To isolate microglia, whole brains were first enzymatically dissociated with the addition of an engulfment inhibitor cocktail to prevent ex vivo engulfment of neuronal debris40. At all steps during microglia isolation, staining and sorting, liquids were supplemented with the engulfment inhibitor cocktail containing the final concentrations of the following reagents: 25 µM Pitstop2 (Abcam, ab120687), 2 µM cytochalasin D (Tocris, 1233), 2 µM wortmannin (Tocris, 1232), 40 µM Dynasore (Tocris, 2897) and 40 µM bafilomycin A1 (Tocris, 1334), with each reagent being prepared as a 1,000× stock. Immediately after extraction of perfused brains, they were placed in 800 µl 1× D-PBS+/+ (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 14040117) on ice. Next, brains were minced on ice using fine scissors for approximately 2 min until brain pieces were small enough to triturate with a p1000 pipette with little resistance during pipetting. Brains were triturated until there was no resistance during pipetting. Brain suspensions were pelleted by centrifugation at 300g for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was removed by pipetting, and an enzymatic cocktail prepared from a Multi-tissue Dissociation kit 1 (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-110-201), consisting of 100 µl enzyme D, 50 µl enzyme R, 12.5 µl enzyme A and 2.4 ml D-PBS+/+, was added. The pellet was resuspended by pipetting, after which the suspensions were transferred to a tube rotator at 37 °C for a 20 min incubation. Halfway through and at the end of this incubation, brain suspensions were triturated with a p1000 approximately 20 times to help to break up brain pieces until the suspension was largely devoid of any visible clumps. After the incubation step, 10 ml ice-cold DPBS+/+ was added to each brain suspension, after which the entire suspension was run through a 70 µm cell strainer into a new tube. Filtered suspensions were centrifuged at 500g for 10 min at 4 °C and the supernatant removed by pipetting. Next, myelin was removed from the preparations using Debris Removal solution (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-109-398). Each brain pellet was resuspended up to 3.1 ml with cold D-PBS+/+ and 0.9 ml Debris Removal solution was added to each pellet and mixed by gentle inversion of the tube. Next, 4 ml cold D-PBS+/+ was overlaid on top of the brain–Debris Removal solution mixture. Samples were centrifuged at 3,000g for 13 min at 4 °C with medium acceleration and 0 break. Following centrifugation, the myelin interface and liquid above it were removed by pipetting, and 11 ml cold DPBS+/+ was mixed with the remaining cell suspension. The cell suspension was centrifuged at 1,000g for 13 min at 4 C with 0 break, and the resulting supernatant removed by pipetting. The largely myelin-depleted cell pellets were resuspended in 80 µl AstroMACS separation buffer (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-117-336) containing 10 µl FcR blocking reagent, mouse (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-092-575) and incubated on ice for 10 min. Next, 10 µl anti-ACSA-2 MicroBeads (Miltenyi, 130-097-679) was mixed into the cell suspension and incubated for 15 min on ice. After incubation, cells were placed in 1 ml AstroMACS separation buffer and centrifuged at 300g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was removed and pellets were resuspended in 500 µl AstroMACS separation buffer and loaded onto a pre-washed LS column (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-042-401). The LS columns were washed 3 times, each time with 3 ml AstroMACS separation buffer. The flow through was retained, as this contained microglia, whereas the cells retained in the column were eluted with 5 ml of AstroMACS separation buffer and retained as an astrocyte fraction used for other experiments. The cell suspensions were washed by centrifugation at 300g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was removed and cells were stained 1:10 with APC/cyanine7 anti-mouse/human CD11b antibody (BioLegend, 101225) and calcein-AM (BioLegend, 425201) at a final concentration of 1× in cell staining buffer (BioLegend, 420201) for 30 min on ice. Cells were washed in 1 ml cell staining buffer by centrifugation at 300g for 10 min at 4 °C. Supernatant was removed and cells were resuspended in an appropriate volume of cell staining buffer for FACS. CD11b+ brain macrophages were sorted by gating on CD11b+, calcein-AM+ singlets on a Sony MA900 cell sorter (Sony Biotechnology). Three biological replicates-worth totalling 900,000 of brain macrophages were pooled into a single replicate and frozen at −80 °C before lysing the cells and enriching for BONCAT-labelled proteins, which was performed on microglia from both BONCAT-labelled samples and wild-type background controls.

Flow cytometry analysis of microglia

Microglia from wild-type and Camk2a-cre;Ai14 hosts were isolated as described above and underwent flow cytometry analysis to determine microglia purity or the expression of tdTomato. In the case of microglia purity analysis, isolated ‘putative’ microglia were stained with the following antibodies: CD11b-BV785 (BioLegend, 101243), CD45-BV421 (BioLegend, 147719), CD206-488 (BioLegend, 141709) and P2ry12-APC (BioLegend, 848005). To analyse tdTomato expression, microglia were stained with CD11b-BV785 (BioLegend, 101243).

Cloning of mouse PheRS(T413G) into an AAV vector

For AAV vectors (used in vivo), the sequences for PheRS(T413G) and the Camk2a promoter were ordered as gBlocks HiFi Gene Fragments from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT). The sequences were derived from previous publications3,51 and modified only to add a 3× Flag tag to the carboxy terminus of PheRS(T413G) and flanks to both fragments to enable Gibson assembly cloning.

For AAV vectors, the PheRS(T413G) gene fragment was first cloned into a pAAV-CAG-GFP (Addgene, 37825) backbone through the removal of GFP by BamHI/EcoRV double-restriction digest followed by Gibson assembly (NEB, E2611S). From this Gibson assembly product, we then removed the CAG promoter by XbaI/NdeI double-restriction digest and cloned in the Camk2a promoter by Gibson assembly. Propagation of AAV plasmids was performed in NEB Stable Competent Escherichia coli (NEB, C3040H) at 30 °C to avoid mutations in the AAV ITR sequences.

For lentivirus vectors (used in vitro), the sequence for PheRS(T413G) was ordered as a gBlock hiFi Gene Fragment from IDT. The sequence was modified to add a 3× Flag tag and p2a sequence to the C terminus of PheRS(T413G) and flanks to enable Gibson Assembly cloning. This fragment was cloned into a pLV-mCherry (Addgene, 36084) backbone by linearizing the backbone by XbaI/Esp3I double-restriction digest followed by Gibson assembly. The cloned plasmid, LV-CMV-PheRS-p2a-mCherry, was propagated in NEB 5-alpha competent E. coli (NEB, C2987H).

AAV production

AAV was custom-produced by VectorBuilder (VectorBuilder). All preparations were ultrapurified and used the PHP.eB serotype.

Cell culture

Cell culture models were used to verify the tagging of proteins during protein synthesis. Py8119 cells were transduced with LV-CMV-PheRS*-p2a-mCherry to stably express PheRS*. B16-F10 cells were stably transfected with a Piggybac vector expressing TyrRS(Y43G) as previously reported3. Cell lines were seeded and cultured in standard conditions (37 °C, 5% CO2, DMEM high glucose with 5% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin and streptomycin). At 24 h after seeding, cycloheximide (Millipore Sigma, C4859-1ML) was added to the cultures to a final concentration of 25μg ml–1 to inhibit protein synthesis. Non-cycloheximide-treated cultures were maintained as controls. One hour later, NCAA was added to both the non-treated and cycloheximide-treated cell cultures to a final concentration of 1 mM. The cultures were incubated for 24 h before lysates were collected for analysis of BONCAT-tagged proteins by in-gel fluorescence. Original cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection. Cell lines were not independently authenticated by the authors and they were not tested for mycoplasma.

Copper-catalysed click reaction on lysates for in-gel fluorescence

Brain tissue was first homogenized by sonication in a strong lysis buffer (8 M urea, 1% SDS, 100 mM choloracetamide (CAA), 20 mM iodoacetamide (IAA), 1 M NaCl and 1× protease inhibitor in 1× PBS). Sonication was performed for at least 3 cycles of 10 s of sonication with at least 5-s breaks between sonication cycles at an amplitude of 90% using a probe sonicator. Homogenates were centrifuged for 15 min at >16,000g at 4 °C. The resultant supernatant was retained, and aliquots were immediately measured by BCA to obtain the protein concentration. The remaining supernatant was frozen at −80 °C until it was further processed to enrich for BONCAT-labelled proteins.

Samples to be compared were normalized to equal protein amounts (110 mg) and brought up to 33.3 µl total with water. A click reaction was performed on the lysates to ‘click’ a fluorophore onto azide side chains of the labelled proteins. The following chemical cocktail was added to the normalized lysates for 1 h with constant shaking to perform the click reaction: 0.83 µl Alexa Fluor 647 alkyne, triethylammonium salt (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A10278) at 5 mM, 1.04 µl copper(II) sulfate (Millipore Sigma, 451657-10G) at 6.68 mM, 2.087 µl THPTA (Click Chemistry Tools, 1010-500) at 33.3 mM, 4.17 µl aminoguanidine hydrochloride (Millipore Sigma, 396494-25G) at 100 mM, 8.33 µl sodium l-ascorbate (Fisher Scientific, A0539500G) at 100 mM and 33.5 µl PBS. Importantly, 20 mM CuSO4 and 50 mM THPTA were mixed at a 1:2 ratio for 15 min before combining the rest of the click reaction. After 1 h of incubation for the click reaction, the reactions were filtered through Zeb Spin Desalting columns, 7 K MWCO, 0.5 ml format (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 89882) following the manufacturer’s protocol to remove unbound fluorophore. The flow through containing the clicked lysates was retained. Next, 21 µl of the clicked lysates was mixed with 7 µl 1× loading buffer, which was prepared by mixing 10 µl 2-mercaptoethanol (Millipore Sigma, M6250-100ML) with 115 µl 4× NuPAGE LDS sample buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, NP0007). Samples were heated at 95 °C for 10 min to denature the proteins. Clicked and denatured lysates were loaded onto a NuPAGE 12%, Bis-Tris gel (Thermo Fisher Scientific, NP0341BOX) and run at 200 V for 45 min. The gel was imaged to detect the Alexa 647-clicked proteins using a LI-COR Odyssey XF imaging system. To detect total loaded protein, gels were stained with GelCode Blue Stain reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 24590), destained in water for at least 1 h and then again imaged using a LI-COR Odyssey XF imaging system. Important in-gel fluorescence results are displayed as uncropped images, including molecular weight ladder and controls, in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Copper-catalysed click reaction for tissue fluorescence microscopy

Tissue sections were prepared for click staining of azide-modified proteins as described in the immunofluorescence staining of tissue sections until the blocking step. After blocking, tissue sections were stained for 1 h in the following click reaction cocktail: 2 µl Alexa Fluor 647/594/555/488 alkyne, triethylammonium salt (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A10278) at 5 mM, 5 µl copper(II) sulfate (Millipore Sigma, 451657-10 G) at 20 mM, 10 µl THPTA (Click Chemistry Tools, 1010-500) at 50 mM, 100 µl aminoguanidine hydrochloride (Millipore Sigma, 396494-25G) at 50 mM, 100 µl sodium l-ascorbate (Fisher Scientific, A0539500G) at 50 mM and 783 µl PBS. Importantly, 20 mM CuSO4 and 50 mM THPTA were mixed at a 1:2 ratio for 15 min before combining the rest of the click reaction. After staining, tissue sections were washed 3 times in Tris-buffered saline–Tween-20 (TBS-T) and either stained further with antibodies as described below in the immunofluorescence staining of tissue sections or mounted and coverslipped.

Immunofluorescence staining of tissue sections

For sucrose-cryopreserved tissues, 40-µm-thick sections were sectioned on a Lecia sliding microtome equipped with a cooling unit and cooling stage. In rare instances in which antigen retrieval was necessary, such as for anti-GFP staining, tissues were incubated in SignalStain Citrate Unmasking solution (Cell Signaling Technology, 14746) diluted to 1× in distilled water for 1 h at 95 °C. After cooling to room temperature, tissues were blocked and permeabilized in 5% normal donkey serum (Jackson Immuno Research, 017-000-121) and 0.3% Triton X-100 (Millipore Sigma, 93443-100ML) in 1× PBS for 1 h. After blocking, tissues were stained with primary antibody diluted in 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (Fisher Scientific, BP9703100) and 0.3% Triton X-100 in 1× PBS overnight at 4 °C with gentle rocking agitation. Primary antibodies were used at the following dilutions: rabbit anti-GFP (Cell Signaling Technology, 2956S) at 1:400; rabbit anti-IBA1 (Fujifilm Wako, 019-19741) at 1:2,000; guinea pig anti-NeuN (Synaptic Systems, 266 004) at 1:1,000; rabbit anti-SATB2 (Synaptic Systems, 327 003) at 1:500; guinea pig anti-parvalbumin (Synaptic Systems, 195 308) at 1:1,000; guinea pig anti-SV2A (Synaptic Systems, 119 004) at 1:500; and rabbit anti-SV2B (Synaptic Systems, 119 102) at 1:500. After primary antibody staining, tissue sections were washed 3 times in TBS-T. After washing, tissue sections were stained with secondary antibodies diluted 1:500 in 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin and 0.3% Triton X-100 in 1× PBS for 3 h at room temperature with gentle rocking agitation. All secondary antibodies recognized the IgG domain of the primary antibodies, were conjugated to Alexa fluorophores and purchased from Jackson Immuno Research. After secondary antibody staining, tissues were washed as described above, briefly stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride (Thermo Fisher Scientific, D1306) and mounted and coverslipped on Superfrost Plus microscope slides (Fisher Scientific, 12-550-15) with Fluoromount-G Slide mounting medium (Fisher Scientific, 50-259-73).

Staining of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections was similar to the methodology used for free-floating sucrose-cryopreserved tissue sections, except that tissue sections on slides were deparaffinized and rehydrated by incubation through a gradient of xylene, 100% ethanol, 90% ethanol, 80% ethanol, 70% ethanol and water, and heat-induced antigen retrieval was always performed by heating slides in 1× SignalStain Citrate Unmasking solution for 10 min in a microwave. Primary antibodies were used at the following dilutions: rabbit anti-SATB2 (Synaptic Systems, 327 003) at 1:500; guinea pig anti-DARPP32 (Synaptic Systems, 382 004); guinea pig anti-PROX1 (Synatpic Systems, 509 005); rabbit anti-RTN3 (Proteintech, 12055-2-AP) at 1:500; rabbit anti-SRSF3 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, PA5-96500) at 1:500; mouse anti-ubiquitin (Cell Signaling Technology, 3936T) at 1:250; and mouse anti-p62 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA5-32835) at 1:250.

Proteostat aggresome staining was only performed on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections following deparaffinization, rehydration, antigen retrieval and blocking of tissue sections. Proteostat (Fisher Scientific, NC0098538) was diluted 1:1,000 in 1× PBS and incubated on tissue sections for 5 min at room temperature and subsequently washed several times with TBS-T. After washing, slides were either coverslipped or subjected to antibody staining.

Microscopy

Images of 5-µm-thick formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue were captured on a Zeiss Axioimager (Zeiss). Images of mounted free-floating 40 µm-thick tissue were captured on a Zeiss LSM 900 (Zeiss). When capturing images to be compared, all imaging parameters and post-acquisition processing parameters were kept identical between images to be compared. The Zeiss Axioimager was accessed in the Stanford University Cell Sciences Imaging Facility (CSIF, RRID: SCR_017787).

Fluorescence image analysis

Heatmaps of raw fluorescence images were created using ImageJ. Images were converted to 8-bit and a colour look-up table was applied.

Quantification of protein aggregate number and area was performed using Fiji. Images were uploaded and the scale set according to an image scale bar. Brightness and contrast were adjusted equally among all images. Images were converted to 8-bit and binary, after which masked particles, which represented aggregates, were analysed and summary statistics related to aggregate number and average area were recorded.

Western blotting

Brain tissue was first homogenized by sonication in a strong lysis buffer (8 M urea, 1% SDS, 100 mM CAA, 20 mM IAA, 1 M NaCl and 1× protease inhibitor in 1× PBS). Sonication was performed for at least 3 cycles of 10 s of sonication with at least 5-s breaks between sonication cycles at an amplitude of 90% using a probe sonicator. Homogenates were centrifuged for 15 min at >16,000g at 4 °C. The resultant supernatant was retained, and aliquots were immediately measured by BCA to obtain protein concentration. The the remaining supernatant was frozen at −80 °C until it was further processed.

Samples to be compared were normalized to equal protein amounts and brought up to equal volumes with water. Samples were denatured and reduced by adding 4× NuPAGE LDS sample buffer to 1× and 2-mercaptoethanol to 20% and heating at 95 °C for 5 min. Denatured and reduced samples were run on a NuPAGE 12%, Bis-Tris gel for approximately 2 h at 110 V. Proteins were transferred to 0.45 µM methanol-activated PVDF membrane by standard wet-transfer methodology at 400 mA for approximately 90 min at 4 °C. Membranes were blocked in Intercept TBS blocking buffer (Fisher Scientific, NC1660550) for 1 h with gentle shaking. After blocking, membranes were incubated in primary antibody diluted 1:1,000 in 5% bovine serum albumin overnight at 4 °C with gentle shaking. Primary antibodies used were rabbit anti-β-actin (Cell Signaling Technology, 4970S) and rabbit anti-HSP90 (Cell Signaling Technology, 4877T). Following primary antibody staining, membranes were washed three times with TBS-T with gentle shaking. Following washes, membranes were stained with IRDye 800CW goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Li-Core, 926-32211) diluted 1:5,000 in 5% bovine serum albumin by light-protected incubation with gentle shaking for 1 h. Following secondary antibody staining, membranes were washed three times with TBS-T with gentle shaking. Last, membranes were imaged using a LI-COR Odyssey XF imaging system. An image of the uncropped membrane image, including molecular weight ladder, is presented in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Insoluble protein and aggregate isolation

The protocol for insoluble and aggregated protein isolation was slightly modified from a previous publication31. Each hemisphere was pulverized to powder by ten hammer strokes to the sample on a liquid-nitrogen-cooled pestle. The resultant homogenate powder was rapidly transferred to tubes on dry ice, pooling three pulverized brains to generate one biological replicate. This methodology of cell lysis is used to preserve aggregates, which could be compromised using other lytic techniques (for example, sonication or detergent-based solutions). The homogenate powder was quickly weighed to avoid thawing. Homogenate was resuspended at 1 g per 5 ml in low-salt buffer (50 mM HEPES, 250 mM sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 1× protease inhibitor and water) on wet ice. Next, for every 0.8 ml homogenate solution, 100 μl 5 M NaCl and 100 μl 10% Sarkosyl was added to the homogenate solution on wet ice. The homogenate was gently sonicated for 3 separate intervals for 5 s at an amplitude of 30% using a probe sonicator (Qsonica, Q125-110) at 4 °C. The homogenate solution was titrated with a p1000 pipette and filtered through a 70 μm cell strainer and centrifuged at 500g for 5 min at 4 °C to obtain a smooth, clump-free homogenate. The protein concentration of the resultant bulk homogenate was determined by BCA and the bulk homogenate was frozen at −80 °C until further processing. Equal protein amounts of bulk protein homogenate were aliquoted from each sample and diluted to 10 mg ml–1 in 1% Sarkosyl buffer (1% Sarkosyl, 0.5 M NaCl and 1× protease inhibitor in low-salt buffer). Samples were ultracentrifuged at 180,000g for 30 min at 4 °C, during which soluble and non-aggregated proteins remained in the supernatant and insoluble and aggregated proteins were pelleted. The supernatant was gently removed and frozen, whereas pellets were washed in 1% Sarkosyl and ultracentrifuged again at 180,000g for 30 min at 4 °C. Pellets were retained and frozen at −80 °C until further processing for various analyses, including enriching for BONCAT-labelled proteins, which was performed on aggregate pellets from both BONCAT-labelled mice and wild-type background control mice. It is important to note that downstream enrichment of BONCAT-labelled proteins from total aggregates should only result in obtaining neuronal proteins that were part of aggregates, but not non-neuronal co-aggregating proteins. The reason for this is due to the buffer required for pull-down (see section below on enrichment of BONCAT-labelled proteins), which both solubilizes and denatures proteins. Introduction of total aggregates to this buffer should result in the release of non-neuronal co-aggregating proteins from neuronal aggregates. The pull-down then selectively enriches for BONCAT-labelled proteins, excluding non-BONCAT-labelled (non-neuronal coaggregating proteins) from further analysis.

RNA extraction for RNA sequencing of microglia and whole brain homogenate

A total of 400,000 sorted Cd11b+ microglia or 1 hemisphere of a whole brain was used as input for RNA extraction. Samples were lysed with QIAzol (Qiagen, 79306). Microglia were vortexed for 30 s in QIAzol for lysis. Hemibrains were mechanically lysed using a Qiagen TissueLyser II (Qiagen, 85300) for 2 cycles, each cycle being 2.5 min at a frequency of 30. Following lysis, RNA was extracted per the instructions from a miRNeasy Micro kit (Qiagen, 217084). Eluted RNA quality was evaluated on an Agilent Bioanalyzer and frozen until used for RNA sequencing library preparation.

RNA sequencing library preparation and sequencing

RNA sequencing libraries were prepared by and sequences were from Novogene. mRNA was purified from total RNA using poly-T oligonucleotide-attached magnetic beads. After fragmentation, the first-strand cDNA was synthesized using random hexamer primers followed by second-strand cDNA synthesis. The library was ready after end repair, A-tailing, adapter ligation, size selection, amplification and purification. The library was checked with Qubit and real-time PCR for quantification and a bioanalyzer for size distribution detection. After library quality control, different libraries were pooled based on the effective concentration and targeted data amount, then subjected to Illumina sequencing (NovaSeq X Plus Series–PE150).

RNA sequencing data processing and analysis

Raw data (raw reads) of fastq format were first processed through fastp software. In this step, clean data (clean reads) were obtained by removing reads containing adapter, reads containing ploy-N and low-quality reads from raw data. At the same time, Q20, Q30 and GC content in the clean data were calculated. All the downstream analyses were based on the clean data with high quality. Reference genome and gene model annotation files were downloaded from the genome website. HISAT2 (v.2.2.1) was used to build the index of the reference genome, and HISAT2 was used to align paired-end clean reads to the reference genome. featureCounts (v.2.0.6) was used to count the reads numbers mapped to each gene. The FPKM of each gene was calculated based on the length of the gene and read counts mapped to this gene. FPKM, the expected number of fragments per kilobase of transcript sequence per millions base pairs sequenced, considers the effect of sequencing depth and gene length for the read counts at the same time and is currently the most commonly used method for estimating gene expression levels.

DESeq2 was used to analyse the RNA sequencing data, with the raw gene counts used as input. The PCA plot and differential expression analysis was performed as described in the DESeq2 vignette.

Enrichment of BONCAT-labelled proteins and preparation for LC–MS

Brain tissue was first homogenized by sonication in a strong lysis buffer (8 M urea, 1% SDS, 100 mM CAA, 20 mM IAA, 1 M NaCl and 1× protease inhibitor in 1× PBS). Sonication was performed for at least 3 cycles of 10 s of sonication with at least 5-s breaks between sonication cycles at an amplitude of 90% using a probe sonicator. Homogenates were centrifuged for 15 min at >16,000g at 4 °C. The resultant supernatant was retained, and aliquots were immediately measured by BCA to obtain protein concentration. The the remaining supernatant was frozen at −80 °C until it was further processed to enrich for BONCAT-labelled proteins.

Samples to be compared were normalized to equal protein amounts (1–2 mg total) and equal volumes in lysis buffer. Lipids were removed by the addition of 10 µl Cleanascite (Fisher Scientific, NC0542680) per 40 µl homogenate and incubation with constant agitation on a thermomixer set to 1,500–2,000 rpm for 10 min. Samples were then centrifuged at >16,000g for 3 min to pellet lipids. The resultant supernatant was retained and 7.5 units of benzonase (Millipore Sigma, 70664-3) was added per 40 µl sample to digest nucleotides over 30 min with constant agitation on a thermomixer set to 1,500–2,000 rpm. Following benzonase treatment, samples were diluted to 1 ml total with lysis buffer and added to 200 µl dry control agarose beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 26150) pre-washed 3 times before sample addition (washed one time with water and two times with 0.8% SDS). Samples were pre-cleared with the control agarose beads to remove nonspecific bead binders by 1 h of light-protected end-over-end rotation. After pre-clearing, samples were centrifuged at 1,000g for 5 min to pellet the plain agarose beads. The resultant supernatant was added to 20 µl dry DBCO beads (Vector, 1034-25) pre-washed 4 times before sample addition (washed once with water and 3 times with 0.8% SDS). BONCAT-labelled protein enrichment with the DBCO beads was performed overnight with light-protected end-over-end rotation. After overnight enrichment of BONCAT-labelled proteins to the DBCO agarose beads, 10 µl of 100 mM ANL (Iris Biotech, HAA1625.0005) was added to each sample to quench the DBCO beads to prevent further protein binding. Quenching was performed for 30 min with light-protected end-over-end rotation. After quenching of the DBCO beads, samples were centrifuged for 5 min at 1,000g and the supernatant was discarded and the DBCO beads were retained. DBCO beads were washed by the addition of 1 ml water and again centrifuged for 5 min at 1,000g. The supernatant was discarded and 0.5 ml 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT; Thermo Fisher Scientific, R0861) was added to each sample. Samples in 1 mM DTT were incubated for 15 min at 70 °C on a thermomixer set to 70 °C to help to remove proteins nonspecifically bound to the DBCO beads. After incubation, samples were centrifuged for 5 min at 1,000g and the resultant supernatant discarded. The DBCO agarose beads were resuspended in 0.5 ml 40 mM IAA (Millipore Sigma, I1149-25G) and incubated light-protected for 30 min to alkylate proteins. After incubation, samples were centrifuged for 5 min at 1000g and the resultant supernatant discarded and the DBCO agarose beads were resuspended in 500 µl 0.8% SDS. The DBCO agarose beads were subjected to extensive washing to further remove nonspecifically bound proteins. This was accomplished by washing each sample with 50 ml of 0.8% SDS, 8 M urea and 20% acetonitrile (Fisher Scientific, PI51101). The speed of washes was enhanced by performing them in Poly-Prep chromatography columns (Bio-Rad, 7311550) connected to a vacuum manifold (Fisher Scientific, NC0994627); approximately 7 ml of a wash was added to the column to resuspend the DBCO agarose beads, and then the vacuum was applied to draw through the wash buffer, leaving DBCO agarose beads in the column. Following all washes, DBCO agarose beads were resuspended in 700 µl of 50 mM HEPES (pH 8.0) and immediately transferred to a 1.5 ml tube. DBCO beads were centrifuged for 5 min at 1,000g. After centrifugation, the supernatant was completely removed and 200 µl 50 mM HEPES (pH 8.0) (Fisher Scientific, AAJ63002-AE) was added to the DBCO agarose beads. Next, 10 µl of a 0.1 µg µl−1 trypsin–Lys-C mix (Promega, V5073) was added to each sample. Proteins bound to the DBCO agarose beads were on-bead digested overnight at 37 °C on a thermomixer set to 1,500–2,000 rpm. The next morning, approximately 16 h after initiating on-bead digestion, samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 1000g. Supernatant containing digested peptides was transferred to a new tube and frozen at −80 °C until further processing. Peptide amounts were quantified using a Pierce Quantitative Peptide Assays & Standards kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 23290). Peptides destined for single-shot LC–MS experiments were desalted using Nest Group Inc BioPureSPN Mini, PROTO 300 C18 columns (Fisher Scientific, NC1678001). The desalting process involved conditioning the column with 200 µl methanol for 5 min followed by centrifugation at 25g until dry, washing the column twice with 200 µl 50% acetonitrile, 5% formic acid (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 28905) by centrifugation at 25g until dry, washing the column 4 times with 5% formic acid by centrifugation at 25g until dry, passing peptides through the column in 40 µl increments by centrifugation at 25g until dry, washing the column 4 times with 200 µl 5% formic acid by centrifugation at 25g until dry, and finally eluting the peptides 2 times with 100 µl 80% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid by centrifugation at 25g. Following desalting, peptides were dried in a speed vac and then maintained at −80 °C before being run by LC–MS.

Peptides destined for TMT and pooling were dried in a speed vac and subsequently resuspended in 25 µl 100 mM TEAB (pH 8.5) (Millipore-Sigma, T7408-100ML). TMTpro 18-plex reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A52047) were reconstituted to 4 µg µl–1 in anhydrous acetonitrile (Millipore-Sigma, 271004-1L). A volume of TMT label was added to the peptide suspension to obtain a minimum of 10 µg TMT per 1 µg peptide and to maintain a TEAB to acetonitrile ratio of 5:2. Peptides were incubated with TMT labels for 2 h with occasional vortexing. Labelling reactions were quenched by adding 2 µl 50% hydroxylamine (Thermo Fisher Scientific, B22202.AE) for 15 min with occasional vortexing. Equal volumes of TMT-labelled peptides were pooled and dried in a speed vac, after which peptides were desalted as described above for single-shot LC–MS preparations.

In-solution digestion of proteins for LC–MS preparation

In-solution digest was used for experiments examining bulk brain proteome and aggregates from wild-type aged mice. Protein was chloroform–methanol precipitated by adding 600 µl methanol, 150 µl chloroform (Millipore-Sigma, C2432-500ML) and 400 µl water to 40 µl protein sample and centrifuging the mixture at 17,000g for 5 min. The upper phase was discarded and 650 µl methanol was added to the sample, vortexed and centrifuged for 17,000g for 5 min. The supernatant was removed and the protein pellet dried for 10 min. The dried protein pellet was resuspended in 10 µl of 8 M urea and 0.1 M Tris-HCL (pH 8.5). Next, 2.25 µl 10 mM DTT was added to the sample and vortexed, followed by incubation on a thermomixer at 30 °C with shaking at 650 rpm for 90 min. Next, 2.83 µl 50 mM IAA was added to the sample and vortexed, followed by light-protected incubation for 40 min. After incubation, 90 µl 50 mM Tris (pH 8) was added to dilute the urea concentration. Last, trypsin–Lys-C mix was added to a mass to mass ratio of 1:50 and the samples were digested overnight at 30 °C with shaking at 650 rpm on a thermomixer. Following digestion, peptides were desalted as described for preparation of BONCAT-labelled proteins.

MS data acquisition and data processing for Bruker timsTOF Pro data

Bruker timsTOF Pro was generally used for small-scale comparisons (eight or fewer samples to be directly compared) and/or when the peptide amount was limited and high sensitivity was still desired. timsTOF was used to acquire the following data in this paper: brain region comparison data in Fig. 1; CMV-cre;BONCAT data from various tissues in the Supplementary Information.

Samples were analysed using a TimsTOF Pro mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics) coupled to a NanoElute system (Bruker Daltonics) with solvent A (0.1% formic acid in water) and solvent B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile).

Dried peptides were reconstituted with solvent A and injected onto the analytical column, Aurora Ultimate CSI 25 × 75 C18 UHPLC column, using a NanoElute system at 50 °C. The peptides were separated and eluted using the following gradient: 0 min 0% B, 0.5 min 5% B, 27 min 30% B, 27.5 min 95% B, 28 min 95% B, 28.1 min 2% B and 32 min 2% B at a flow rate of 300 nl min–1.

Eluted peptides were measured in DDA-PASEF mode using timsControl 3.0. The source parameters were 1,400 V for capillary voltage, 3.0 l min–1 for dry gas and 180 °C for dry temperature using Captive Spray (Bruker Daltonics). The MS1 and MS2 spectra were captured from 100 to 1,700 m/z in data-dependent parallel accumulation-serial fragmentation (PASEF) mode with 4 PASEF MS/MS frames in 1 complete frame. The ion mobility range (1/K0) was set to 0.85 to 1.30 Vs cm–2. The target intensity and intensity threshold were set to 20,000 and 2,500 in MS2 scheduling with active exclusion activated and set to 0.4 min. 27 eV and 45 eV of collision energies were allocated for 1/K0 = 0.85 Vs cm–2 and 1/K0 = 1.30 Vs cm−2, respectively.

Data captured were processed using Peaks Studio (v.10.6 built on 21 December 2020, Bioinformatics Solution) for sequence database search with the Swiss-Prot Mouse database. Mass error tolerance was set to 20 ppm and 0.05 Da for parent and fragment ions. Carbamidomethylation of cysteine was set as a fixed modification. Protein N-terminal acetylation and methionine oxidation were set as variable modifications, with a maximum of three variable post-translational modifications allowed per peptide. Estimate FDR with decoy fusion was activated. Both FDR for peptides and proteins were set to 1% for filtering.

MS data acquisition and data processing for Bruker timsTOF Ultra data

Bruker timsTOF Ultra was used for experiments in which the peptide amount was limited and high sensitivity was still desired. timsTOF Ultra was used to acquire the following data in this paper: aged neuronal aggregates and neuron-to-microglia protein transfer.

Peptide extracts were loaded on the trapping column, Waters ACQUITY UPLC M-Class Symmetry C18 Trap column, 100 A, 5 µm, 180 µm × 20 mm and eluted with the analytical column, IonOpticks Aurora Elite CSI 15 × 75 C18 UHPLC column. The elution gradient was set to 0 min 2% B; 3.5 min 28% B; 4 min 50% B; 5.5 min 85% B and 15 min 85% B with a flow rate of 0.65µl min–1 from 0 min to 3.5 min and reduced to 0.3µl min–1 at 4 min until the gradient ended.

Eluted peptides were measured in diaPASEF mode with a base method m/z range of 100–1,700 and 1/K0 range of 0.64–1.45 V s−1 cm−2. The PASET m/z window range was 400 to 1,000 and the mobility range was 0.64–1.37 V·s·cm−2 with a 96 ms cycle time at 100% duty cycle. The source parameters were 1,600 V for capillary voltage, 3.0 l min–1 for dry gas and 180 °C for dry temperature using Captive Spray (Bruker Daltonics). 20 eV and 59 eV of collision energies were allocated for 1/K0 = 0.6 Vs cm–2 and 1/K0 = 1.6 Vs cm–2, respectively.

Data captured were processed using Spectronaut (v.19.3 build on 23 October 2024, Biognosys) for directDIA search with Swiss-Prot Mouse database downloaded on 3 March 2023. The default setting was used, but with a slight modification of minimum peptide length of six and cross-run normalization deactivated.

MS data acquisition and data processing for Thermo Eclipse data

A Thermo Eclipse was used for any experiments using TMT, as this instrument is capable of running TMT samples. TMT, and by extension the Thermo Eclipse, were used for larger-scale comparisons to avoid any time-associated ‘drifts’ that would make comparisons between samples run on an instrument far apart in time less accurate. TMT was also used when quantitative precision and consistent peptide identification across replicates or samples to be compared were critical, such as for the protein degradation experiments in which the quantification of all time points of a single region and single age was instrumental to the overall success of the experiment. TMT labelling and Thermo Eclipse were used for the following experiments: transgenic line comparisons in Fig. 1; protein degradation experiments in Figs. 2 and 3; AAV and transgenic mouse comparisons in the Supplementary Data; aged versus young in Supplementary Data.

Samples were analysed using an Easy-nLC 1200 coupled to a Thermo Scientific Orbitrap Eclipse Tribrid mass spectrometer with EasySpray Ion source and FAIMS Pro interface. Digested samples were reconstituted in 0.1% formic acid in water and were loaded to a trap column (Thermo Scientific Acclaim PepMap C18 column, 2 cm × 75 µm i.d., 3 µm) and separated on a Thermo Scientific Acclaim PepMap RSLC C18 column, 25 cm × 75 µm i.d., 2 µm. Solvent A was 0.1% formic acid in water and solvent B was 80% acetonitrile in water with 0.1% formic acid. The gradient was ramped from 2% B to 40% B in 179 min at a flow rate of 300 nl min–1. The column temperature was set at 50 °C.

TMT-labelled peptides were analysed by data-dependent acquisition mode using the synchronous precursor selection (SPS) MS3 real time search (RTS) approach. For full MS scan, the resolution was set at 60,000 and the mass range was set to 350–1,500 m/z. Normalized AGC target was set at 100% and the maximum injection time was 50 ms. The most abundant multiply charged (charge 2–7) parent ions were selected for CID MS2 in the ion trap. The CID collision energy was set at 35%. RTS using the UniProt Mus musculus database was performed. Carbamidomethyl on cysteine (C) and TMTpro 16plex on lysine (K) and peptide terminal were set as static modifications. Oxidation on methionine (M) was set as variable modifications. Up to ten parent ions from MS2 will be selected by SPS for HCD MS3. MS3 spectra were acquired at 30,000 resolution (at m/z 200) in an Orbitrap MS with 55% normalized HCD collision energy. The cycle time was set at 2 s, and 3 experiments were run for different FAIMS compensation voltage: −45 V, −60 V and −70 V.

TMT data were processed using Thermo Scientific Proteome Discoverer software (v.2.4). Spectra were searched against the UniProt Mus musculus database using the SEQUEST HT search engine. A maximum of two missed cleavage sites was set for protein identification. Static modifications included carbamidomethylation (C) and TMTpro (K and peptide N terminus). Variable modifications included oxidation (M) and acetylation (protein N terminus). Resulting peptide hits were filtered for maximum 1% FDR using the Percolator algorithm. The MS3 approach generated CID MS2 spectra for identification and HCD MS3 for quantification. Precursor mass tolerance was set as 10 ppm and fragment mass tolerance for CID MS 2 Spectra obtained by Ion Trap was set as 0.6 Da. The peak integration tolerance of reporter ions generated from SPS MS3 was set to 20 ppm. For the MS2 methods, reporter ion quantification was performed on FTMS MS2 spectra and for identification, where they were searched with precursor mass tolerance of 10 ppm and fragment mass tolerance of 0.02 Da.

For the reporter ion quantification in all methods, no normalization and scaling were applied. The average reporter singal-to-noise ratio threshold was set to ten. Correction for the isotopic impurity of reporter Quan values was applied.

MS data analysis

Basic fold change over background analysis and protein identification

For experiments in which the goal was to simply quantify the number of different proteins labelled in BONCAT-labelled samples and/or identify proteins labelled with confidence over the background, non-normalized data were used as input. The reason for using non-normalized data is because the background samples were expected to have few proteins and low abundance relative to labelled samples, and this inherent difference should be preserved for analyses of labelled samples relative to background samples; normalizing would remove this inherent difference. The following steps were performed on the data: data were log2 transformed, proteins were filtered based on possessing valid values in a certain number of replicates in at least one group, missing values were replaced by imputation (width of 0.3 and downshift of 1.8), fold change was calculated for each protein between BONCAT-labelled replicates versus the respective background control replicates, and P values for these comparisons were derived from a two-tailed t-test. The number of replicates that were required to possess a valid value for a protein depended on the number of replicates used in the experiment, but in all cases required over 50% of the replicates in at least one group to possess a valid value for any given protein. The Camk2a-cre;BONCAT benchmarking experiment required 3 out of 4 replicates to have valid values in at least one group. The AAV Camk2a-cre;PheRS* experiment required 3 out of 4 replicates to have valid values in at least one group. The CMV-cre;BONCAT experiments required 2 out of 2 replicates to have valid values in at least one group. The neuronal aggregate experiment required 6 out of 11 labelled replicates to have valid values in at least one group. The neuronal protein transfer experiment required at least 6 labelled replicates to have valid values when comparing all ages to the background, at least 6 out of 10 labelled replicates to have valid values when compared with the background in the context of labelled proteins in young mice, and at least 5 out of 8 labelled replicates to have valid values when compared with the background in the context of labelled proteins in aged mice. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant in all analyses, following precedent set by other protein enrichment MS publications10,13. The fold change cut-off between two groups being compared was log2[FC] > 1.

PCA

For PCA, individual data frames from each group being compared underwent filtering as described above in the basic fold change analysis with any proteins remaining after filtering in each group being retained as true hits. Subsequently, data frames for each group containing the raw abundance values were merged with all proteins being retained regardless of whether they were shared or not among the three groups. The raw abundance values were log2 transformed, and missing values, which were mostly proteins that were identified in one BONCAT line or region but not others, were replaced by imputation (width of 0.3 and downshift of 1.8). By implementing imputation, which is necessary for PCA, each sample possessed the same number and identity of proteins, not only the number shown in the Venn diagram comparing the BONCAT mouse lines. These values were then used for PCA in Perseus software.

Comparing protein abundance between different groups

In a few experiments, labelled protein fold changes between two or more experimental conditions that were also labelled were compared. The experiments include regional comparisons in Fig. 1, aged versus young comparison in Extended Data Fig. 2, and aged versus young comparison of microglia derived from labelled mice in Fig. 5. In these experiments, data frames from each group being compared underwent filtering as described above in the basic fold change analysis with any proteins remaining after filtering in each group being retained as true hits for further analysis. Data frames of true hits for each group were merged to keep all proteins identified among all groups. The raw abundance values for the retained proteins from all groups were log2 transformed, and missing values, which were mostly proteins that were identified in one condition but not the other, were replaced by imputation (width of 0.3 and downshift of 1.8). The fold change for these values were calculated for each protein between conditions, and P values for these comparisons were derived from a two-tailed t-test. In the case of the three-way regional comparison in Fig. 1, the resultant values were z scored before visualizing in a heatmap.

Protein turnover analysis

As described above, non-normalized data were used as input for protein turnover analyses with a similar rationale to preserve inherent differences in protein abundance between time points, with less protein being expected at each successive time point progressing into the chase period; normalization would risk losing these inherent differences. First, the log2[FC] in protein abundance between time point 1 replicates and wild-type background control replicates (n = 2 per age per region combination) was calculated. Any proteins enriched >1.5 in time point 1 over the background control were considered for further analysis, and the other proteins were discarded as background proteins. This fold change over background filtering was performed for each age and region combination separately. Time point 1 was used in this filtering approach rather than other time points because time point 1 represents the time point of maximal labelling and would give the fairest evaluation of background compared with later time points at which enriched proteins successively approach levels closer to that of wild-type controls and would lead to discarding more proteins, probably unjustly. Background was further mediated by subtracting the average of the background samples from the average of each individual time point for each protein, similar to how background is subtracted for colorimetric assays. When making comparisons between different ages of a single region, proteins were further filtered to those that were commonly detected between ages and detected in all replicates, with the only exception being the degradation kinetic trajectories shown in Fig. 2d. With this relatively stringent filtering approach, we ensured that equally reliable half-life predictions and trajectory analysis were performed without a need to assign uncertainty values due to varying drop-out rates. We did not impute values for this experiment as few missing values were in a plex (consisting of all time points for one region and one age), but most missing values were between plexes (meaning protein X could be present in one plex but missing from all others), and there was the risk that imputing values of proteins missing entirely between different ages and regions would not produce meaningful or reliable results.

For kinetic degradation trajectory analyses, the mean of each replicate of each time point in each age and region was calculated. Time point 1 was considered 100% protein remaining for each protein in each region and age and the other time point percentages were calculated by dividing the average abundance of the successive time point by the average abundance of time point 1. Differences between all subsequent time points were calculated, and only decreasing trajectories or trajectories with an up to 5% increase between two time points were retained. Because labelled protein should either decrease or remain stable during a pulse-chase experiment, we considered an increase above 5% between time points as caused by measurement noise, we elected to exclude proteins that exceeded this 5% threshold between any two consecutive time points. Of note, in a study that used SILAC labelling in vitro to measure protein degradation20, a threshold of 130% protein remaining was used (see figure 1d in that paper), which is much less stringent than that which we apply. For this experiment, a few technical notes should be made. First, all replicates of all time points from one region and one age were labelled with TMTs and combined into one plex to enable the most accurate quantitative analysis of protein degradation. Second, from the resulting data in each plex, for any given protein in one region and for one age, the amount of protein present or remaining at time point 1 was the maximum and considered 100% and the per cent remaining in subsequent time points was the fraction of the average abundance of biological replicates at that time point divided by the average abundance of biological replicates of time point 1. To compare protein turnover between different regions and/or ages, the percentages of protein remaining at specific times were compared. Notably, by comparing the per cent protein remaining between regions and ages rather than directly comparing raw abundance values, natural differences in protein synthesis and/or variability in protein labelling would not skew analyses and data interpretation. Trajectories were clustered using fuzzy c-means clustering. The optimal number of clusters was determined using minimal centroid distance. For comparison with the aged groups, matching proteins in that group were separated in the same cluster distribution. Integrals for each protein in each cluster were calculated based on the trajectories used for clustering. The integral for each protein was calculated by trapezoidal numerical integration using MatLab trapz. ΔIntegral values were derived by calculating the difference between the integral value of the aged protein and the respective young protein, whereby average ΔIntegral values were determined similarly with the addition of dividing by the number of different protein species analysed (for example, the number of proteins in a certain cluster). The significance of the average ΔIntegral values was determined by a one-way ANOVA with significant comparisons determined by a Tukey tests.

For half-life estimations, we normalized the mean trajectory for each protein such that the first measurement at time point 1 corresponds to the value of one. These normalized trajectories were fitted using the method of least squares, meaning that the objective function to minimize was defined as the sum of the square of the difference between the goal function and the data. The functions describing the one-level and two-level model were given as \({\Lambda }_{1}(t)=\exp (-{k}_{A}t)\) and \({\Lambda }_{2}(t)=G(t)-G(7+{t}_{p})/G(0)-G({t}_{p})\)

$$\mathrm{with}\,G(t)=({k}_{AB}({k}_{AB}+{k}_{A})\exp (\,-\,{k}_{B}t)+{k}_{B}({k}_{A}-{k}_{B})\exp (\,-\,({k}_{AB}+{k}_{A})t)).$$

In these formulas, k is the rate constant, t is time, tp is a fixed time parameter, Λ1(t) is a simple exponential decay, Λ2(t) is a normalized difference of the function G(t). The parameters minimizing the objective function were then found using MatLab fmincon. For the one-level model, we calculated the half-life directly from the decay rate \({k}_{A}.\) The half-life for the two-level model was found by linear interpolation. After calculating the AIC, where AIC = n log(RSS/n) + 2k) for both models, we chose the model with the lower AIC and its corresponding half-life. These modelling approaches were derived from previous publications that studied protein degradation by pulse-chase methodology and subsequently estimated half-life values19,20. It is important to note that as shown in the Extended Data, the modelling approach exhibited good correlation with direct interpolation of half-lives from degradation trajectories. Because of the good correlation and the benefit of being able to estimate the half-life of proteins that did not reach or go below 50% remaining in our data, we used the modelling approach. Likewise, as also shown in the Extended Data, we alternatively calculated half-lives based on individual replicates, which also strongly correlated with the results based on the averaging of all replicates of one time point. To elaborate on the approach based on individual replicates, the data were normalized by computing the mean value at time point 1 and dividing all values by this. A base-10 logarithm was then applied to the normalized data to reduce variance in each time point. The logarithmically transformed normalized trajectories, consisting of four values per time point, were fitted using scipy.optimize.minimize. The functions used for the fit were chosen as the logarithm of the previously used functions for one-level and two-level model. The parameters obtained from the fit were then used as described above to calculate the half-life values.

Other methods for analysing protein degradation data have been implemented and thoroughly described. The suitability of the analysis method depends on many features of the data, including the number of time points studied, biological replicate number, data noise, among others. We tested different approaches and settled on those we reported above because they performed best with our data, achieving a balance of confidence in the reported results without being overly stringent and discarding too much data or introducing artificial data.

It is important to note there are many experimental and computational factors that affect ultimate half-life calculations. These factors include, but are not limited to, rate of protein synthesis, use of pulse-chase labelling versus continuous labelling, the length of time between the final pulse of the labelling reagent (such as the NCAA) and the collection of the sample, and choice of interpolation or modelling methods to estimate half-life. These factors are inescapable caveats of current protein turnover measurements and have been thoroughly reviewed52.

Extracting protein clusters from the heatmap

To extract the proteins that defined the clusters, and by extension brain regions, in the z scored heatmap comparing the striatum, hippocampus and motor cortex, hierarchical clustering information was extracted from the heatmap. First, the command “pl$tree_row” was used to extract hierarchical clustering information from the heatmap for the protein clusters. Next, the hierarchical protein tree was divided into three clusters using the “cutree” function, with three clusters chosen on the visual distinction of three gene clusters in the heatmap. Last, protein IDs were extracted by the command “which(lbl=x)”, where x represents the cluster number.

Protein feature analysis

Protein features were extracted from a comprehensive table of proteins and protein features from a previous publication21 and matched to the proteins of interest in this study. Comparisons of protein features were made between the groups of interest as reported in the main text with statistical analyses being performed either by t-test or one-way ANOVA with a Tukey test.

GO analysis

GO analyses were performed using the ShinyGO web application (http://bioinformatics.sdstate.edu/go/)53. Protein lists converted to standard gene symbols were uploaded to the application as input. Default parameters were used to run the analysis unless otherwise specified. The background brain proteome used was derived from a previous brain proteome publication54 and that used by SynGO42. The output, visuals and tables, including enriched terms, enrichment FDR, number of genes in the pathway and fold enrichment, were filtered by significance (FDR < 0.05) and reported in this paper.

Cell-type annotation of proteins

To annotate cell types, we used the ClusterMole R package (v.1.1). This package leverages a curated database of cell-type marker genes from Panglao DB and Cell Marker databases to assign cell-type probabilities to differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Specifically, ClusterMole compares the set of upregulated and downregulated genes identified to known cell-type marker signatures. A hypergeometric test was used to calculate P values for overrepresentation of cell-type signatures in the DEG sets. When no cell type was annotated to a particular protein, it was considered non-cell-type specific.

Overlap with H-MAGMA

Neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental risk genes were derived from the H-MAGMA study28. By analysing gene regulatory relationships in the disease-relevant tissue, this study identified neurobiologically relevant target genes, improving on existing MAGMA studies. Lists of adult brain risk genes and summary statistics were downloaded from the GitHub repository of the studies (https://github.com/thewonlab/H-MAGMA). Genes with reported P < 0.05 were considered risk genes.

Signal peptide analysis

Signal peptide prediction was performed by querying protein sequences in SignalP, a server that predicts the presence of signal peptides and the location of their cleavage sites in proteins from Archaea, Gram-positive bacteria, Gram-negative bacteria and Eukarya55. Individual protein sequences were retrieved from UniProt and entered one by one into the SignalP browser search (https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/SignalP-6.0/). We considered protein sequences with signal peptide scores of >0.1 to contain a bona fide signal peptide sequence and to be considered secreted. Proteins with signal peptide scores of <0.1 but >0.02 were considered to contain a likely signal peptide sequence. Proteins with signal peptide scores <0.02 were considered to unlikely contain a bona fide signal peptide sequence and therefore considered unlikely to be secreted. Details of SignalP analysis can be found in the original publication55.

ExoCarta analysis

Classification of proteins as exosome cargo was performed by querying proteins on ExoCarta, a manually curated web-based compendium of exosomal proteins, RNAs and lipids56. Individual gene symbols or protein names were entered one by one into the ExoCarta browser query search (http://exocarta.org/query.html). If the search resulted in any mammalian hit, it was considered a potential exosome cargo. Details of ExoCarta analysis can be found in the original publication56.

SynGO analysis

An in-depth analysis of synaptic ontologies of a protein list was performed by using SynGO, an evidence-based, expert-curated resource for synapse function and gene enrichment studies42. Gene lists were input to the SynGO browser (https://www.syngoportal.org) and default analysis parameters were applied. Visualizations of enrichment analysis on SynGO cellular components and biological processes were exported from the SynGo browser. Details of SynGO analysis can be found in the original publication42.

Enrichr analysis

Enrichr57 permits the analysis of enriched pathways in a list of genes and was used to analyse the RNA sequencing data. DEG lists (log2[FC] > 1.5 and adjusted P < 0.05) were input to the Enrichr browser (https://maayanlab.cloud/Enrichr/) and the cell-types category was selected for further exploration, with the CellMarker database results being used in the final analysis.

UniProt ID to gene symbol conversion

UniProt IDs were converted to gene symbols using the Retrieve/ID mapping web tool in UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org/id-mapping). In cases when multiple gene symbols were returned for a single UniProt ID, the entry name—the unique gene symbol identifier associated with the UniProt ID—was used for most in-text references and visualizations. All gene symbols associated with a single UniProt ID are listed in the Supplementary Tables with the entry name listed first in the list.

Mining microglia proteomic data

Analysis of mouse and human microglia proteomes was performed on processed LC–MS data from a previous publication16. The reported copy number of the four replicates of freshly isolated 3.5-month-old male mouse microglia were averaged, and any protein with an average copy number of >0 was considered as detected. This same analysis was performed on the five replicates of freshly isolated human microglia, derived from female individuals aged 6 years, 22 years, 22 years, 45 years and 61 years.

Mining Allen Brain Cell Atlas data

The Allen Brain Cell Atlas58 ‘Whole mouse brain 10xv2 single cell’ dataset was mined to examine neuronal and microglia marker genes as specified in the paper. The dataset was down sampled to 10,000 cells and marker genes were determined using the ‘FindAllMarkers’ command in Seurat59. For neurotransmitter class and neuron class marker genes, the minimum fraction of cells expressing the gene was set to 25% and the log2[FC] threshold was set to 0.25 and only DEGs with adjusted P < 0.05 were further considered. Analyses comparing microglia versus neuronal marker genes were conducted similarly, except to be considered differentially expressed, the gene had to be expressed in at least 50% of one population (for example, neurons) and no more than 10% of the other population (for example, microglia) and the adjusted P was set to <0.05.

Mining microglia LysoTag data

Microglia LysoTag data were derived from a pre-print41. Two different microglia LysoTag models were used in the analyses: one model driven by Cx3cr1-cre and the other model driven by Fcrl2-cre. For each model, we considered a protein a hit if the q value was <0.05 and the protein was enriched by immunoprecipitation in the LysoTag model compared with the mock immunoprecipitation from wild-type mice.

Hypergeometric test for protein overlap and overenrichment

Hypergeometric tests were performed by using the equation

$$P(X\ge x)=1-\mathop{\sum }\limits_{k=0}^{x-1}\frac{\left(\genfrac{}{}{0ex}{}{K}{k}\right)\left(\genfrac{}{}{0ex}{}{M-K}{N-k}\right)}{\left(\genfrac{}{}{0ex}{}{M}{N}\right)}$$

where K is the total number of proteins in one list of proteins being overlapped, M is the total number of proteins in the other list to which K is overlapped, x is the number of proteins overlapping between the lists, and N is the total population size, which was 4,220, the number of unique BONCAT-labelled neuronal proteins we could maximally detect in the Camk2a-cre;PheRS* model among the experiments shown in Fig. 1 (benchmarking experiment), Fig. 4 (aged aggregates) and Fig. 5 (microglia from aged mice). All other numeric inputs were derived from the Venn diagram displayed in Fig. 5.

Expected overlap was performed using the equation Expected overlap = KM/N, and enrichment was calculated by dividing the observed overlap by the expected overlap.

Statistics and reproducibility

Details of statistical methods are described in relevant subsections above and/or indicated in the figure legends. All t-tests were two-tailed. ANOVA calculations were ordinary one-way ANOVA. q values were calculated using the qvalue command from Bioconductor in R Studio and Benjamini–Hochberg-corrected P values were calculated using the p.adjust command with the method being ‘BH’ in R Studio.

The data in the following figure panels were not repeated: Extended data Fig. 1a,m.

The data in the following figure panels were repeated in a total of three independent experiments: Figs. 1c,j, 2b,c, 4a,f–h and 5c and Extended Data Figs. 1c,n, 2f,g, 3b–d and 7g.

Data visualizations

Unless stated otherwise above, data visualizations were performed in R studio (Posit Software), GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software), FlowJo (Becton, Dickinson and Company) or Adobe Illustrator (AdobeA) with aesthetic enhancements performed in Adobe Illustrator. Renderings of mice in Figs. 2a and 5a and Extended Data Fig. 3i were created in BioRender. Guldner, I. (2025) https://BioRender.com/9itwqmf.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.