Back in the 1960s, when Ritalin (methylphenidate) was first approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating behavioural problems, parents and teachers alike were impressed by the remarkable and immediate effects of stimulants on children’s ability to stay on task. Kids who had previously spun like a top, unable to concentrate or switch focus from one task to another, suddenly settled down and got on with their work.

“For many people, it’s like a miracle,” says Edmund Sonuga-Barke, a developmental psychologist at King’s College London.

Today, stimulants are still the front line of treatment for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and they are considered to be one of the most effective medications across the board. They have “the highest effect size we have in psychiatry, and among the highest in general medicine”, says Samuele Cortese, a child psychiatrist and ADHD researcher at the University of Southampton, UK. But controversy has long surrounded these drugs, spurring a desire to find alternatives.

Nature Outlook: ADHD

In the 1970s, concern about the abuse of stimulants led to a backlash against prescribing them for children. The medical consensus is that supervised oral stimulants are safe, but the side effects — including loss of appetite, sleep problems, mood swings and stomach aches — can be problematic for some. Furthermore, many people with ADHD also have other issues, such as anxiety or a history of addiction, that make stimulants less suitable. For up to 30% of people with ADHD1, stimulants just don’t work or aren’t tolerable.

There are also broader societal issues with stimulants, says Stephen Faraone, a psychiatrist and neuroscientist at Upstate Medical University in Syracuse, New York. The increasing number of ADHD diagnoses has led to occasional shortages of these drugs, leaving people without the medications they have grown accustomed to. Because stimulants are controlled substances, they come with onerous paperwork and visits to the doctor, creating barriers to access. And some medications are being used by people without a prescription, such as students who want to stay up late studying. “There’s a small but growing problem with misuse and diversion,” says Faraone.

Fortunately, there are some non-stimulant options for ADHD, and researchers are trying to find more, based on a better understanding of the genetics, pharmacology and symptomology of the condition. Some drugs have been repurposed, from blood-pressure medications or antidepressants, and some aim for different targets, including neurotransmitters produced by gut microbes. Other research is focused on retraining the ADHD brain through talking therapy, video games, neurofeedback or brain stimulation.

Given the societal issues, and because some people will do just as well or even better on non-stimulants, it might be time to rethink the general advice on prescription, says Faraone. “All current guidelines say you should start with a stimulant medication. Maybe we should reconsider that.”

Stimulating work

More than two dozen stimulant formulations have been approved by the FDA for ADHD in the United States. The two main active ingredients are methylphenidate (as found in Ritalin) and amphetamines (as found in Adderall). These drugs, along with other similar stimulants, typically increase the amount of dopamine and noradrenaline in the brain, which are neurotransmitters that affect mood, increase alertness and focus attention. Stimulants typically start working immediately and have no residual effects if you stop taking them, making it easy to try various drugs or doses, or to target different needs on different days.

These drugs ameliorate the three diagnostic symptoms of ADHD: inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity. And there is evidence that stimulants have other benefits, too. One review found improvements in measures of quality of life, from risk avoidance to school achievement, self-esteem and relationships2. They have also been shown to reduce criminal behaviour, physical accidents, car crashes and suicides.

The durability of these gains is debated, however. There is some evidence, for example, that the effects of stimulants wear off after a few years3. The jury is also still out on whether ADHD medications improve long-term learning or academic success — indeed, some researchers have concluded that they don’t4,5. One prominent study found, for example, that although some of the drugs increase the time spent on work, they don’t increase the quality of that work. Instead, the drugs give people the impression that they’re doing better on tasks without actually improving their performance6.

Brain boost

For those for whom stimulants don’t work or aren’t desirable, there are alternatives. The first non-stimulant medication for ADHD, atomoxetine, was approved by the FDA in 2002. It is a selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor (NRI), a drug class commonly used as antidepressants. These, like stimulants, effectively increase the amount of noradrenaline in the brain.

The main benefit of NRIs is that they lack addictive properties and are therefore not controlled substances. Moreover, when they start to kick in after a few weeks of use, they last longer than quick-acting and quick-fading stimulants. A second NRI, called viloxazine, was approved for ADHD in 2021. Although they are an important addition to the list of ADHD medications, NRIs are not always ideal. One side effect can be an increase in suicidal thoughts. And although they work in a similar way to stimulants, they aren’t as effective for most people.

Alongside NRIs, the second main type of approved non-stimulant ADHD drugs are α2A agonists: blood-pressure drugs that have been repurposed for ADHD. These include guanfacine (Intuniv) and clonidine (Kapvay), which were approved by the FDA for ADHD in 2009 and 2010.

The beneficial effects of α2A agonists on higher brain function were first noticed by Amy Arnsten, a neuroscientist at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, in studies with elderly monkeys in the 1980s — specifically, a female rhesus monkey named Chat, who was about 30 years old and experiencing cognitive decline. “She could not remember where her favourite treat was hidden for more than like, two seconds without being distracted,” Arnsten recalls. Arnsten was trialling different drugs, blinded, “and lo and behold, this day, this monkey was incredibly focused. She did near perfectly. And I was like, what is this?” The magic elixir, it turned out, was guanfacine. “We’ve chased that ever since,” says Arnsten.

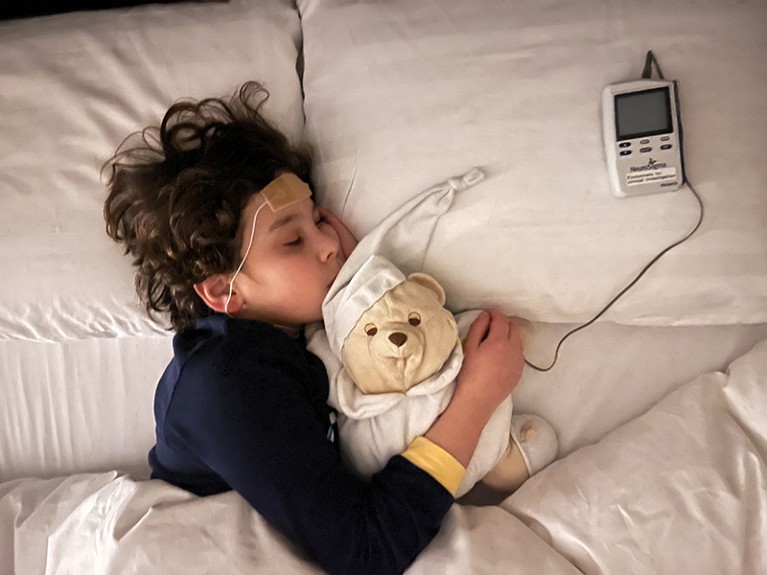

The Monarch external trigeminal nerve stimulation device is FDA-approved to treat ADHD.Credit: Aldo Conti

Arnsten and her colleagues went on to show that α2A agonists act on the prefrontal cortex — the part of the brain just behind the forehead that is associated with high-level thinking and working memory. They found that stress can initiate a flood of potassium signalling that essentially takes the prefrontal cortex offline, shunting decision-making processes instead to faster, more primitive parts of the brain. That can “save your life if you’re cut off on the highway, but it can really be very detrimental with public speaking or if you’re trying to solve climate change”, says Arnsten. The α2A agonists clog up the potassium channels and keep the prefrontal cortex connected, with a host of benefits for a variety of mental conditions, including ADHD7.

For children, neither NRIs nor α2A agonists are on average as effective as stimulants against ADHD’s core symptoms. But Arnsten argues that the agonists are useful in other ways that ADHD tests don’t always capture. The ADHD medication rating scales measure the narrowing of attention by stimulants, she says. “That’s helpful for doing things like maths problems with very linear thinking. But it’s not helpful when you’re trying to be creative.” What you really want, she says, is not to narrow your attention, but to guide it thoughtfully.

As with all drugs, α2A agonists don’t work for everyone. “For some kids, and adults, it’s like magic,” Arnsten says. “It has corrected what’s biologically missing. For others, it doesn’t help, or they’re very sensitive to the sedation or the hypertension.” Because these agonists work in a different way to stimulants, some physicians prescribe them both. “The side effects counteract, and the beneficial effects can add,” Arnsten says.

Outside the box

Because drugs that inhibit the reuptake of dopamine or noradrenaline work for ADHD, some drug developers are exploring whether compounds that inhibit the reuptake of other neurotransmitters might work even better. Consider viloxazine, for example. The drug is already well established as an inhibitor for the reuptake of noradrenaline. More-recent studies show that the drug also modulates levels of serotonin, a neurotransmitter that is similar to dopamine in that they both affect mood, appetite and sleep8.

Solriamfetol, which is currently used to prevent excessive sleepiness in people with narcolepsy or sleep apnoea, is a noradrenaline and dopamine reuptake inhibitor, and centanafadine is a noradrenaline, dopamine and serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Both have shown promising results in phase III clinical trials. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which are commonly used as antidepressants, have also been investigated. None of these has yet been approved for ADHD, however, and none has shown the same remarkable effectiveness as the stimulants that are already available.

The EndeavorRx is a video game that has been found to improve symptoms of inattention in ADHD.Credit: Akili

Researchers are also working on a long list of other targets, including γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), the nervous system’s main inhibitory neurotransmitter, which acts to calm the brain9; glutamate, an excitatory neurotransmitter that is crucial for learning and is a precursor to GABA; orexins, which are neuropeptides that regulate wakefulness; and nicotine receptors, which can have knock-on effects on dopamine. Other drug classes are also being investigated, including cannabinoid compounds that ease anxiety or restlessness; and cortisol-releasing hormone antagonists that can suppress a specific stress response. Researchers also aim to see whether some popular alternative therapies, such as saffron extracts, are effective.

Some of these ideas might be promising, but are not likely to be game-changers, says Cortese, who has reviewed the ADHD drugs in the pipeline10,11. “It’s difficult to beat stimulants,” he says. “So far, everything we find has a lower effect size and comparable tolerability.” Still, he adds, the increasing diversity of options for treating ADHD is a good thing, including new formulations of existing drugs that might last longer or kick in more quickly when needed.

Brain training

Parents and patients often ask about non-medical interventions for ADHD, says Katya Rubia, a cognitive neuroscientist at King’s College London. That might include exercise or dietary changes, as well as talking therapy or neural techniques.

Neurofeedback and neurostimulation aim to exercise and develop parts of the brain that are typically underdeveloped in people with ADHD. On average, says Rubia, people with ADHD have about 2–3% less grey matter, along with smaller structures in key areas of the frontal lobe. Neurofeedback takes electroencephalogram (EEG) readings or functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) images of the brain and then gives the user a visual representation of what’s going on to help them learn how to increase activation in targeted brain areas. Neurostimulation delivers mild electrical or magnetic signals to the scalp through patches or headbands to increase brain activity. Both ideas make a lot of sense and have garnered considerable attention from researchers and companies.

The results of studies into both techniques have, however, been patchy and often disappointing. High-quality, long-term studies of neurofeedback, in particular, show that although people can learn to change their brain activity, this doesn’t translate into clinical benefits12. Neurostimulation might be more promising than neurofeedback, although the studies so far are small, says Rubia, which makes it hard to judge. “I think it’s too new to say if it works or not,” she says.

Rubia’s own work on a form of neural stimulation called transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) has shown promise. She and colleagues tested adults using tDCS for 30 minutes a day for 4 weeks — one of the longest studies of tDCS — and found a large positive effect for ADHD, greater than that for stimulant medication13. But these results need to be replicated and studied further, she says.

A variety of other neural-stimulation techniques and devices are being explored by companies to treat conditions from ADHD to depression. Only one, the Monarch external trigeminal nerve stimulation (eTNS) system, has been approved by the FDA. A 2019 study of that device showed it had an effect similar to that of non-stimulant drugs14. But Rubia says that her own blinded and placebo-controlled study of TNS shows no improvements for ADHD15.

The only other FDA-approved device for ADHD is EndeavorRx, a straightforward video game with no neural feedback, which got the green light in 2020. The game asks users to focus on one colour of monster while ignoring another, helping the user to develop the skills of focused attention and task switching. An independent review of assessments by parents and teachers found that EndeavorRx does lead to improvements in measures of inattention, although not by as much as those produced by medication16. In general, says Cortese, cognitive training seems to improve working memory, but not the behavioural issues of ADHD.

Most physicians and researchers would like to see a world in which each individual’s brain chemistry and genetics are better understood, and in which the end goal of any treatment, whether pharmacological or not, is clearer. “Our dream would be: I see the patient, I do a scan, I do a genetic test,” says Cortese. “Given your characteristics, this is the medication, the treatment for you. We are very, very far from this.”

Researchers, doctors and people with ADHD agree on the desirability of having a range of options for treating ADHD, with the understanding that the best combination might be different for each individual. There’s a lot left to do. “The more thoughtful we can be about what’s causing the ADHD, the more we can find out what’s wrong, the more we can do to treat it,” says Arnsten.