Transit observations and analysis

We analysed a heterogeneous dataset of light curves from space- and ground-based telescopes (Supplementary Table 1) to measure transit times for the ultimate purpose of modelling TTVs. We used PyMC344, exoplanet (https://docs.exoplanet.codes/en/stable/)45 and starry46 to fit the light curve, incorporating tailored models for correlated noise and instrumental systematics appropriate for each dataset.

Our analysis of the K2 and Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) light curves involved two distinct approaches with different noise models. For the joint analysis of all transits in both light curves (described below), we modelled stellar variability as a Gaussian process47. By contrast, for measuring individual transit times (see below), a third-order basis spline was sufficient to model the local correlated noise.

To account for systematics in the Spitzer data, we used pixel-level decorrelation (PLD)48, which uses a linear model with a design matrix formed by the PLD basis vectors (see below for more details). For the ground-based datasets, we included a linear model with a design matrix formed by airmass, pixel centroids, and the pixel response function peak and width covariates, when available.

The limb-darkening coefficients were calculated using stellar parameters from ref. 2 by interpolation of the parameters tabulated by refs. 49,50. These were fixed for individual transit fits but sampled with uninformative priors in the joint K2 and TESS analysis described below.

We used Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno optimization51 as implemented in scipy.optimize for initial parameter estimates, followed by posterior sampling with the No-U-Turn Sampler52, an efficient gradient-based Hamiltonian Monte Carlo sampler implemented in PyMC3. The chains were well mixed (Gelman–Rubin statistic less than about 1.01) with negligible sampling error.

We first performed a joint fit of K2 and TESS data assuming a linear ephemeris (see below). We then measured all individual transit times uniformly using Gaussian priors from the joint fit for Rp/R⋆, b (the transit impact parameter), and T14 (the total transit duration), and uniform priors for Tc (the transit centre time) centred on predicted times. We verified that Tc posteriors were Gaussian and isolated well from prior edges.

In all individual transit fits, we assumed Gaussian independent and identically distributed noise and included a jitter parameter σjit to account for underestimated photometric uncertainties. The log-likelihood was, thus,

$$\textln\mathcalL=-\frac12\textln| \varSigma | -\frac12\bfr^\rmT\varSigma ^-1\bfr+\rmconst.,$$

where Σ is the diagonal covariance matrix with entries equal to the total variance (that is, the ith entry is \(\sigma _\rmtot,i^2=\sigma _\rmobs,i^2+\sigma _\rmjit^2\), where σobs,i is the observational uncertainty of the ith data point), and r is the residual vector (\(\bfr=[\widehaty_1-y_1,\widehaty_2-y_2,\ldots ,\widehaty_n-y_n]\), where \(\widehaty\) is the model and y is the data consisting of n measurements). When a given transit event was observed by several telescopes (for example, at Las Cumbres Observatory (LCO))53, or several band-passes from the same instrument (for example, from MuSCAT3)54, we jointly fitted all light curves covering the same event.

We obtained ground-based follow-up transit observations from a variety of facilities spanning several observing seasons. Early in the project, observations were distributed diversely among a half-dozen telescopes, but later we focused almost exclusively on the LCO telescope network, which enabled both the acquisition of data and its analysis to be conducted more uniformly. The individual dates, facilities, band-passes and exposure times of these observations are listed in chronological order in Supplementary Table 1. The measured transit times are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Joint analysis of the K2 and TESS light curves

V1298 Tau (EPIC 210818897) was observed between 7 February and 23 April 2015 during campaign 4 of the K2 mission9. We analysed the K2 light curve produced by the EVEREST pipeline (https://github.com/rodluger/everest)55,56, which is available at the Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes (MAST) (https://archive.stsci.edu/hlsp/everest).

V1298 Tau (TIC 15756231) was observed at 2-min cadence in Sectors 43 and 44 (16 September to 6 November 2021) of the TESS mission57 as part of the Director’s Discretionary Time (DDT) programme 036 (PI T. David).

We conducted a joint fit to the K2 and TESS light curves assuming a linear ephemeris, using a Gaussian process to account for correlated noise arising from a combination of stellar variability and instrumental systematics (based on the tutorial available at https://gallery.exoplanet.codes/tutorials/lc-multi/). We used a simple-harmonic-oscillator covariance function with a power spectral density given by:

$$S(\omega )=\sqrt\frac2\rm\pi \fracS_\omega _^4(\omega ^2-\omega _^2)^2+\omega _^2\omega ^2/Q^2,$$

where ω is the angular frequency, ω0 is the undamped angular frequency of the oscillator and S0 is a scale factor that sets the amplitude of the variability. This was re-parameterized by the undamped period of the oscillator ρ (defined as ρ = 2π/ω0), the standard deviation of the process σ (defined as \(\sigma =\sqrtS_\omega _Q\)) and the quality factor Q (fixed to 1/3). Like our model for individual transits, we included a photometric jitter term (σjit), the square of which was added to the diagonal of the covariance matrix. The likelihood was, thus, identical to that shown for individual transits above, but the covariance matrix contained non-zero off-diagonal elements determined by the covariance function. The results of this fit are shown in Extended Data Fig. 2 and the posteriors are summarized in Extended Data Table 1.

Individual K2 and TESS transits

To create a uniform transit-timing dataset, we analysed individual transits from the long-baseline K2 and TESS light curves in the same manner as our short-duration follow-up observations. We constructed individual datasets from windows of three times the transit duration centred on each transit event. When there were overlapping transits, we used the longest transit duration and centred the window on the approximate midpoint of the dimming event. Unlike follow-up datasets, which are often partial transits, stellar variability is typically nonlinear on the timescale of these datasets. To account for this, we included a third-order basis spline with five evenly spaced knots. The transits of V1298 Tau c on 10 and 26 October 2021 ut resulted in poor-quality fits, probably due to the presence of short-timescale red noise close to ingress or egress or a low signal-to-noise ratio; as the timing posteriors from these fits were highly non-Gaussian, we discarded them from subsequent analyses.

Spitzer

We used the ephemeris derived from the K2 observations2 to predict transits of V1298 Tau b within Spitzer visibility windows in 2019. Subsequently, we did the same for V1298 Tau c,d using the ephemerides from ref. 3. Another transit of V1298 Tau b was scheduled in early 2020 using an updated ephemeris based on ref. 2 and the first Spitzer observation of that planet. The Spitzer data and best-fitting transit models are shown in Extended Data Fig. 3.

The first epoch of Spitzer observations of V1298 Tau were acquired as part of the DDT programme 14227 (PI E. Mamajek) and executed on 1 June 2019 ut. The second epoch of Spitzer observations were acquired as part of the target of opportunity programme 14011 (PI E. Newton) and executed on 28 December 2019 ut. In both epochs, data were acquired with channel 2 of the infrared array camera (IRAC) onboard Spitzer (with effective wavelength λeff = 4.5 μm) in the subarray mode using 2-s exposures. A third epoch of Spitzer observations were acquired in IRAC channel 1 (λeff = 3.6 μm) as part of DDT 14276 (PI K. Todorov) and executed on 4 January 2020 ut.

We extracted photometry following ref. 58 and modelled the instrumental systematics using PLD, which combines normalized pixel light curves as basis vectors in a linear model:

$$M_\rmPLD^t(\boldsymbol\alpha )=\frac\sum _i=1^9c_iP_i^t\sum _i=1^9P_i^t,$$

where Pi is the ith pixel light curve, the superscript t denotes the value at a specific time step, and α = c1, …, c9 are the coefficients of the PLD basis vectors. The first epoch, which captured a partial transit of V1298 Tau b over approximately 11.5 h, was fitted well by including a linear trend in addition to PLD. The second epoch, which contained transits of both planets c and d over an approximately 14-h baseline, exhibited significant nonlinear variability that required the inclusion of a basis spline. Similarly, the third epoch, containing a full transit of planet b over approximately 12.5 h, also warranted the inclusion of a basis spline; although IRAC1 systematics are typically larger than those of IRAC2, PLD performed well and we attribute this to stellar variability. We validated our approach of selecting the baseline model by inspecting the fit residuals for the longest and most complex observation (the second epoch). A quantitative comparison confirmed that a basis spline was strongly preferred over a simple linear trend by the Bayesian information criterion59.

Ground-based observations

Most of our follow-up transit observations were obtained from 2020 to 2024 using LCO. We primarily used the Sinistro53 and MuSCAT3 instruments on the 1-m and 2-m telescopes, respectively.

In addition to LCO, we used data from a variety of other facilities, including Apache Point Observatory (APO)/Astrophysical Research Consortium Telescope Imaging Camera (ARCTIC)60, Fred Lawrence Whipple Observatory/KeplerCam61, WIYN/half degree imager62, Three-hundred MilliMeter Telescope63, MuSCAT64, MuSCAT265 and Araki/ADLER. Data were obtained using a variety of filters and reduced using standard pipelines and methods66,67,68,69,70,71. See Supplementary Information for more details.

Recovering planet e

The outermost planet, V1298 Tau e, transited only once during the K2 mission. TESS recovered transits of all four planets, including a second transit of planet e10. It was not clear how many transits occurred between the K2 and TESS observations given the 6.5-year gap between the two campaigns. Thus, a discrete comb of periods was allowed, such that P = Δt/n, where Δt is the measured time between transit midpoints and the integer \(n=1,2,3,\ldots ,n_\max \). The upper bound on n, and thus, the lower bound on a period of 42.7 days, was provided by the absence of other transits by planet e within the K2 and TESS time series10.

By the summer of 2022, a preliminary version of our timing dataset had revealed large TTVs of planet b that we assumed were dominated by interactions with planet e. We ran a suite of TTV models at each of the possible Pe between 42.7 days and 120 days. Few trial periods yielded good fits to the timing dataset, and dynamical simulations revealed that only a fraction of those were stable over \(\mathcalO(1^6)\) years. One of the stable solutions with Pe = 48.7 days corresponded to a near 2:1 commensurability for the b–e pair, a common configuration among the Kepler planets exhibiting large and detectable TTVs. With this prediction, we recovered a partial transit of planet e from the ground on 18 October 2022. LCO datasets used to recover planet e and confirm its orbital period are shown in Extended Data Fig. 4.

Datasets containing flares

Several observations were affected by stellar flares and were excluded from our TTV analyses to avoid potential timing measurement biases. These datasets were modelled using our standard approach, augmented with a parametric flare model72 (Extended Data Fig. 5). Significant flares were observed in ARCTIC data (12 October 2020; see also ref. 38), KeplerCam data (24 September 2023) and LCO data (18 December 2023), with amplitudes ranging from 6 parts per thousand (ppt) to 42 ppt and timescales of 14 min to 21 min. The parameters of these flares are detailed in the Supplementary Information, and they may prove valuable for future studies of the activity of V1298 Tau.

Mass constraints from analytic TTV modelling

To build intuition for the system dynamics, we first performed a preliminary analysis using analytic models of TTVs. Based on the foundational analytic frameworks for TTVs11,12,73, we determined that the system dynamics can be effectively decoupled into two pairs of planets: c–d and b–e.

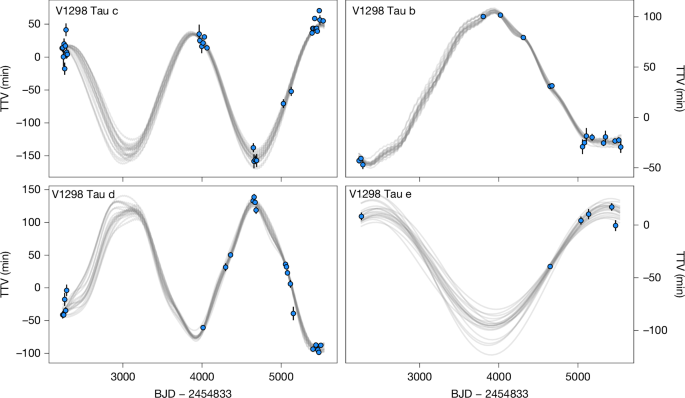

To quantify the TTV behaviour, we fitted a multi-harmonic sinusoidal model to the transit time series (see Supplementary Information for the model equations). We explored the posterior distributions of the 16 model parameters using a Markov chain Monte Carlo sampler, like approaches used by other public TTV analysis codes74,75. The posteriors of these parameters are listed in Supplementary Table 3, and the model fits are shown in Extended Data Fig. 6.

The results for the c–d pair are consistent with the planets being in a near-resonant regime. The TTVs are described well by a single sinusoid with a period Pcd = 1,604 ± 12 days and an r.m.s. of the residuals of only 11 min. This sinusoidal signal is dominated by variations in the planetary mean longitudes (λ), characteristic of systems very close to resonance. The ratio of the TTV amplitudes is sensitive to the planetary mass ratio, indicating nearly equal masses (Md/Mc ≈ 1.2). From the full fit, we derived preliminary masses \(M_\rmc\approx 2.7_-0.8^+1.7\) M⊕ and \(M_\rmd\approx 3.2_-1.0^+2.1\) M⊕.

By contrast, the b–e pair is described well by a simpler, linear TTV model, as it is further from resonance. The TTVs arising from variations in mean longitude and eccentricity have the same frequency in this regime. In this case, a well-known degeneracy exists between the planet masses and their orbital eccentricities16,76, leading to broader initial constraints of \(M_\rmb=31_-17^+14\) M⊕ and \(M_\rme=24_-8^+4\) M⊕. A full theoretical treatment and a discussion of strategies for breaking the mass–eccentricity degeneracy, such as measuring secondary eclipse times77, can be found in the Supplementary Information.

Mass constraints from N-body TTV modelling

Guided by our analytic models, our primary analysis relies on a full N-body dynamical model to derive the final planet parameters. We fitted the model to the observed transit times using a Bayesian framework. To be robust against outlier measurements, we adopted a log-likelihood function based on Student’s t-distribution78,79, with priors as listed in Extended Data Table 2. The posterior probability distribution was sampled using the No-U-Turn Sampler80,81. The model is implemented in JAX to enable automatic differentiation and is available as part of the jnkepler package27,82. The full mathematical details of the model implementation, the log-likelihood equation and the sampler set-up are provided in the Supplementary Information. The resulting mass and eccentricity posterior distributions are shown in Extended Data Fig. 7.

To verify the physical plausibility of our solution, we performed a detailed dynamical analysis of the posterior. We investigated both the long-term stability and the resonant state of the system using several complementary methods. First, to assess stability, we used a probabilistic classifier (SPOCK)83 on 1,000 samples from our posterior, which yielded a median stability probability of 95% over 109 orbits. We confirmed this with direct N-body integrations of 128 samples for 1 Myr, which showed that the system is deeply stable and regular (minimum separation over 12RH (mutual Hill radii), maximum semimajor axis drift of less than 0.01%, and MEGNO (Mean Exponential Growth factor of Nearby Orbits) = 2.000). As a final check, we integrated 32 posterior samples for 4 Myr, all of which were found to be stable. Second, to characterize the resonant state, our integrations show that all classical resonant angles are circulating, which we confirmed by projecting our solution onto the resonant representative plane12. The solution lies clearly outside the resonant island where libration would occur, confirming the non-resonant nature of the system.

Initial thermal state and planetary evolution

Young planets with hydrogen-dominated atmospheres contract over time due to mass loss and thermal evolution. Reference 32 showed that young planets with measured masses and radii can be used to constrain their initial entropies. Planets with a measured mass and radius have a degeneracy between their hydrogen envelope mass fraction and their thermal state. The hydrogen envelope mass of the planet can be reduced and compensated for by an increase in its entropy. However, this can only go so far; the envelope mass cannot be reduced arbitrarily to the point where it is too small to survive mass loss. Thus, one can place a bound on the initial entropy of the planet such that it survives until today. To perform this calculation, we computed a grid of MESA evolutionary models that include photoevaporation (a comparison with ref. 84 indicates that these planets will be undergoing photoevaporation rather than core-powered mass loss). This model grid comprised 36 core masses, 128 initial mass fractions and 96 initial entropies. We used an identical method to that in ref. 32. We then compared this model grid with the observed masses and radii of the V1298 Tau planets to derive posterior distributions of the core masses, initial envelope mass fractions and initial entropies (which we encode as the initial Kelvin–Helmholtz cooling timescale of the planets). Our results indicate that all the planets had initial envelope mass fractions and core masses that are consistent with typical sub-Neptunes at billion year ages. Furthermore, the initial cooling timescales are constrained to require boil-off for planets c and d, whereas an evolution without boil-off cannot be ruled out for the outer planets. Extended Data Fig. 8 shows the models that best reproduce the present-day masses and radii of planets c and d. Interestingly, they require an initial low entropy; that is, an initial Kelvin–Helmholtz contraction time that is longer than the age of the system. Furthermore, if one considers only models with a high initial entropy, one can match the current mass or radius, but not both.