In February 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) tried to predict which strains of influenza were going to pose the biggest threat in that year’s Northern Hemisphere flu season. It failed.

On the basis of surveillance data on which strains were circulating, the WHO selected four that would become the foundation of that year’s vaccine. One was an H3N2 virus strain that was the most prevalent of that particular subtype, at that moment. But by the time the vaccine was making its way into people’s arms that autumn, a different version of the virus had taken over — and the vaccine was only 6% effective at protecting against it1. That year’s Northern Hemisphere flu season was more severe than the five that had preceded it, and lasted weeks longer than any in the previous decade.

Nature Spotlight: Influenza

This problem of antigenic drift — when gene mutations cause components of the influenza virus to change, and it evolves away from the vaccines designed to keep it in check — could be reduced by the development of a universal flu vaccine. A shot that provides broad coverage against a wide array of strains could improve efficacy significantly from the 40–60% reduction in risk that flu vaccines typically achieve2. It would also eliminate the need for WHO’s twice-yearly meetings to predict which viral strains to guard against, the subsequent scramble to manufacture the vaccine and the need for people to be vaccinated year after year.

Some strategies to improve the effectiveness of the flu vaccine and reduce the need for annual shots have made it into early clinical trials3. A major thrust of these efforts is to coax the immune system to respond to a part of the flu virus that it normally pays little attention to. Ordinarily, the immune system produces antibodies that focus on a particular part of haemagglutinin, a protein on the surface of the virus that allows it to enter cells. Antibodies clamp to haemagglutinin and block the virus from attaching. Haemagglutinin has 18 subtypes: H1 to H18. And, unfortunately, haemagglutinin can evolve rapidly, changing its shape so that antibodies can no longer bind to it. “What we’re trying to do is trick the immune system into attacking a part of the influenza virus that it typically doesn’t attack,” says Florian Krammer, a vaccinologist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Haemagglutinin is a stalk, rising from the virus surface, topped by a ball-shaped head. The immune system focuses most of its efforts here. “The head domain sticks out of the virus, so it’s very easy for B-cell receptors, which in the end become antibodies, to recognize that part,” Krammer says. “The stalk is a little bit more hidden.” Krammer treats this as a challenge, and is trying to amplify the immune response to the haemagglutinin stalk.

A second protein called neuraminidase, which helps the virus spread to other cells, has 11 subtypes. Although viruses with any combination of these haemagglutinin and neuraminidase subtypes can infect people, the two currently circulating in humans are H1N1 and H3N2. Krammer and his colleagues create new versions of the virus by taking H1 stalks and replacing the heads with those from other subtypes, such as H14 or H8. Apart from newborn babies, most people have been either infected with or vaccinated against flu — or both — and so have a pre-existing immune response. When presented with a chimaera protein (say, an H1 stalk and an H8 head) the immune system recognizes the part it has seen before (the stalk)and reacts to that. “That weakens the response to the head and strengthens the response to this stalk,” Krammer says.

And a stronger reaction to the stalk should, in turn, make it harder for the virus to evade the immune response. The stalk plays a crucial part in allowing the virus to fuse with the host cell, and undergoes a series of structural changes during fusion. Any mutation that interferes with those changes renders the virus ineffective, meaning the stalk can’t evolve in response to the immune system as readily as the head can. The stalk also doesn’t vary much between virus strains, so immunity against this part provides broader protection.

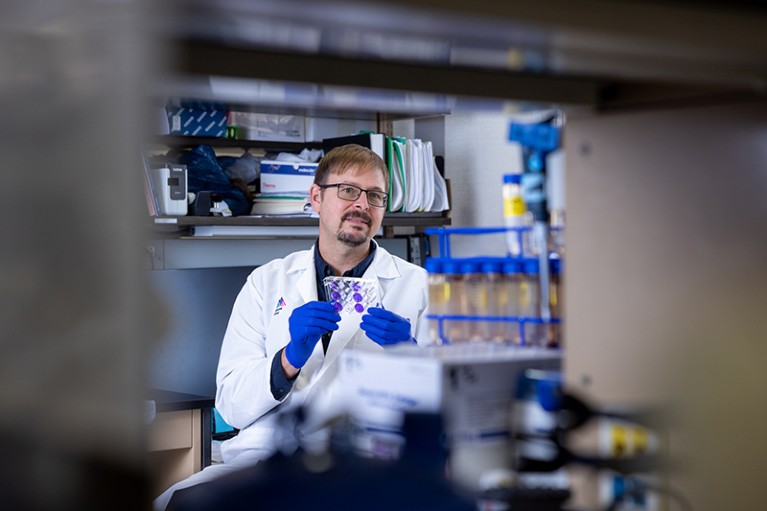

In 2020, Krammer and his colleagues tested a vaccine in a small phase I clinical trial3. They showed that it induced a large number of antibodies to target an H1 stalk. Although the COVID-19 pandemic put the work on hold, it has since resumed. The next step will be to try the same with an H3 stalk, and to combine the two to see whether the result generates a broad antiviral response. “It’s going slowly, but it’s going,” Krammer says.

At Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, microbiologist Nicholas Heaton is also trying to get the immune system to look beyond the haemagglutinin head. His aim is to get it to notice other sites on the virus at which antibodies can bind, known as epitopes. “Normally, the immune system would focus on that haemagglutinin head domain. It’s obsessed with it,” Heaton says. “If you remove it, then you say, out of everything that’s left, what do you like? And so you get these responses to other epitopes.”

Heaton and his colleagues used gene editing to create more than 80,000 variations of haemagglutinin with different changes to a specific part of the head domain, but with the same stalk4. The variety of head-domain epitopes meant that the immune system focused its attention on the stalk, leading to a significant increase in stalk antibodies when tested in ferrets and mice. But Heaton didn’t want to create a new immune response at the expense of the old one. He, therefore, also used conventional methods to create a virus particle that elicited the typical haemagglutinin-head-focused response, and then mixed the two types to achieve broader immunity.

The variant epitopes also seem to induce some immunity, and many might help to inhibit the virus. The stalk-binding antibodies don’t actually neutralize the virus, Heaton says, but they can help the immune system to recognize it and clear it faster, theoretically lowering the viral burden and thus the severity of the infection. “People who would have stayed out of work for two days won’t even feel sick,” Heaton says. People who might have died could instead experience just a few days of illness. “Those are the types of shifts that we think would be accomplished by lower peak viral burden and faster clearance of the virus.”

Predicting evolution

Not all research focuses on inducing antibodies to the stalk. Ted Ross, a vaccinologist and global director of vaccine development at the Cleveland Clinic Florida Research and Innovation Center in Port St Lucie, uses computational modelling to find head epitopes to attack. “Human beings have, from natural infection, lots of stalk antibodies already, and we still get infected with influenza,” Ross says. “So I don’t know if the stalk approach is going to be the only mechanism for a universal approach.” The upshot, Ross, says, is that “if you combine head, stalk, other antigens and even T cells, you’re going to have a much broader vaccine than just focusing on one”.

Vaccinologist Florian Krammer is working on a flu vaccine that could protect against multiple strains of influenza.Credit: Mount Sinai Health System

Ross and his team developed a technology to search for genetic sequences in flu viruses that are less likely to mutate over time, making them better targets for a broad vaccine. Since high-throughput sequencing machines became mainstream, around 2010, vast numbers of flu viruses collected by a global surveillance system have had their genomes sequenced, Ross says. That includes not only strains isolated from humans, but also other potential sources of flu infections, such as those from pigs and ducks.

He and his team developed the Computationally Optimized Broadly Reactive Antigen (COBRA) system5. COBRA searches those genomes for sequences that change very little across viruses. Machine-learning models simulate how those conserved sequences might change as a result of the evolutionary pressure of an immune response. Using historical data and those predictions, the scientists can then design a vaccine for the virus that they think might be coming, and test that. “We’re letting viral evolution tell us how to make our vaccine,” Ross says.

To test its method, the team used data only up to 2009 to design a vaccine. The researchers gave the vaccine to mice that had never been exposed to flu, and then exposed the mice to viral strains of both H1N1 and H3N2 from 2009 to 20196. In an encouraging result, the vaccine provided the mice with good levels of protection against these ‘future’ strains.

In a vastly different approach, Jonah Sacha, a molecular biologist at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, is trying to enlist another part of the immune system — T cells. He is using a platform created at the university to develop vaccines for HIV (now in clinical trials) and tuberculosis.

Instead of focusing on surface antigens, Sacha and his colleagues looked at internal structural proteins that build the shell of the virus. Those proteins are so critical to the structure of the virus that significant mutations would destroy it. “The internal proteins don’t change that much, because they can’t,” Sacha says.

They selected three: a matrix protein, M1; a nucleocapsid protein; and a viral polymerase, PB1. They then inserted those into a cytomegalovirus (CMV), which infects humans but does not cause illness. T cells in the body’s mucosal surfaces, such as the lining of the respiratory system, keep CMV in check. Sacha hoped that, if CMV carried flu proteins, it would train those T cells to attack the flu virus, too.

He and his team produced a vaccine based on the virus that caused the 1918 flu pandemic — recreated from samples found in frozen tissues from people who were infected — and injected it into macaques. He then exposed the macaques to the virulent H5N1 bird flu, a potential cause of the next pandemic. All six unvaccinated monkeys died within a week, but 6 of the 11 vaccinated animals survived7. In other words, a vaccine based on one of the oldest available flu viruses provided protection against a strain that had accumulated around a century’s worth of mutations.

Sacha’s hope is that these flu-resistant T cells will remain on guard for life, although even such a vaccine might not provide perfect protection. “I think that it will be a component of a successful universal influenza vaccine,” he says. “I really believe, when we have a universal influenza vaccine, it will engage both T cells and antibodies.”

Many researchers think that the idea of a universal flu vaccine might be overselling the concept. “I hate that title,” Heaton says. “I think we’re making a promise that we can never fulfil, even before the research starts. If we made a vaccine that was ten times better than what we have, that would save millions of people a year. And this still wouldn’t be universal.”

Ross says that a truly universal vaccine could be years away, if it’s even possible. “I would be happy with a vaccine that lasted three to five years before it had to be updated,” he says. “That would be a huge improvement. It would help vaccine manufacturers. It would reduce costs. It would lead to year-round production of the vaccine instead of seasonal production.”