Animals and ethics

Mice were housed in individually ventilated cages (IVC) under controlled climate (temperature: 20–24 °C; humidity: 45–65%) in a normal light:dark cycle (12 h:12 h) with ad libitum access to laboratory food pellets and water. Wild-type C57BL/6 J (Charles River) mice, and SERT-Cre51 (014554, Jackson), VGAT-IRES-Cre (028862, Jackson) and VGLUT2-IRES-Cre (016963, Jackson) mice of 8–12 weeks of age from either sex were used for the experiments. We detected no influence of sex on the results, and data from male and female mice were pooled. All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with UK Home Office regulations (Animal Welfare Act of 2006), under project licence PPL PD867676F, following local ethical approval by the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre Animal Welfare Ethical Review Body. Reporting followed ARRIVE guidelines.

Virus vector injection and optic fibre implantation

Prior to surgery, mice were subcutaneously injected with the analgesic Metacam (1 mg per kg). Mice were anaesthetized with isoflurane (5% induction, 1.2–1.8% maintenance) in oxygen (0.9 l per min flow rate). Body temperature was maintained at 36.5 °C, using a controlled heating pad. The eyes were protected from light by aluminium foil and from drying by Xailin lubricating eye ointment. Using ear bars, mice were head-fixed on a stereotactic device (Kopf, model 940) and using a scalpel blade the scalp was cut along with the midline to expose the skull. Small craniotomies were made with a dental drill (0.4 or 0.5 mm diameter) and AAV virus (60 nl) was injected into the target brain regions using a pulled glass pipette (approximately 20 µm inner diameter at the tip) and a programmable nanolitre volume injector (Nanoject III, Drummond Scientific). Fifteen minutes after the injection, the glass pipette was retracted and the incision was either sutured or glued (Vetbond), or optic fibres (for optogenetics: 200 µm diameter; for photometry: 400 µm diameter) were implanted. After cementing a custom-designed metal head plate to the skull (using light-cure Tetric EvoFlow cement (Ivoclar Vivadent), empowered by OptiBond Universal (Kerr) primer), the optic fibres were inserted 200 µm (for optogenetics) or 50 µm (for photometry) above the target brain regions and cemented to the skull. After recovery, the mice were returned to their cage. Eighteen to twenty days after the virus injection and fibre implantation surgery, mice with expression of an optogenetic opsin (ChR2 for neuronal or axonal activation, ChrimsonR for neuronal activation during photometry recording, stGtACR252 for neuronal suppression, or eNpHR3.0 for axonal suppression), tdTomato (control for optogenetic stimulation) or GCaMP6f (for calcium photometry recording) were used for optogenetics/photometry experiments. After recovery, the mice were returned to their cage.

Brain regions and coordinates (from Bregma) used for virus injections: MRN (anterior–posterior (AP): −4.4 mm, medial–lateral (ML): 0.0 mm, dorsal–ventral (DV): 4.3 mm or AP: −5.5 mm, ML: 0.0 mm, DV: 4.4 mm, AP angle: 14°), LHb (AP: −1.8 mm, ML: 0.4 mm, DV: 2.7 mm) and LHA (AP: −1.6 mm, ML: 1.0 mm, DV: 5.2 mm). For optogenetic stimulation, we used AAV9-hEF1a-DIO-mCherry-hChR2 (University of Zurich; V80-9, a gift from K. Deisseroth), AAV1-CAG-hChR2-tdTomato (virus made in the host institute, using Addgene plasmid #28017 a gift from K. Svoboda), AAV9-hSyn-SIO-FusionRed-stGtACR2 (virus made in the host institute, using Addgene plasmid #105677, a gift from O. Yizhar), AAV1-Ef1a-DIO-eNpHR3.0-EYFP (Addgene #26966-AAV1, a gift from K. Deisseroth), AAV1-hSyn-eNpHR3.0-EYFP (virus made in the host institute, using Addgene plasmid #26972, a gift from K. Deisseroth), AAV1-hSyn-DIO-ChrimsonR-tdTomato (virus made in the host institute), AAV1.Syn.ChrimsonR.tdTomato (Addgene #59171-AAV1, a gift from E. Boyden) and AAV1-CAG-tdTomato (Addgene #59462-AAV1, a gift from E. Boyden), for fibre photometry recordings, AAV1-Syn-flex-GCaMP6f (virus made in the host institute, using Addgene plasmid #100833, a gift from D. Kim and GENIE Project) and for retrograde tracing experiments, retroAAV-CAG-GFP and retroAAV-CAG-tdTomato (virus made in the host institute, using Addgene plasmids #37825 and #59462, gifts from E. Boyden). Viruses for optogenetics, photometry and retrograde tracing were diluted to about 5 × 1012 vg ml−1, about 2 × 1012 vg ml−1 and about 8 × 1012 vg ml−1, respectively. For rabies virus tracing53,54, we first injected helper viruses AAV1-EF1a-flex-H2B-EGFP-P2A-N2cG and AAV1-EF1a-flex-EGFP-T2A-TVA (made at the host institute; diluted to about 1 × 1013 vg ml−1, 40 nl), in the target brain region (MRN), followed 10 days later by injection of rabies virus N2cG-deleted rabies-EnvA-mCherry53, (made at the host institute; diluted to about 1 × 108 vg ml−1, 40 nl) at the same location. Seven days after the rabies virus injection, mice were transcardially perfused for automated serial-section two-photon imaging of the whole brain55,56.

Optogenetics

Laser stimulation protocols were created and run through custom-made scripts in MATLAB or Python. For neuronal or axonal activation by ChR2 and neuronal suppression by stGtACR2 a 473 nm laser (OBIS 473 nm LX 75 mW LASER SYSTEM, Coherent), coupled to a 200 µm fibre patch cable through an achromatic fibre port (Thorlabs), was used. For axonal suppression by eNpHR3.0 and neuronal activation by ChrimsonR we used 594 nm (OBIS 594 nm LS 40 mW Laser System: Fiber Pigtail: FC, Coherent) and 647 nm (OBIS 647 nm LX 120 mW Laser System, Coherent; coupled to a 200 µm fibre patch cable through an achromatic fibre port (Thorlabs)) lasers, respectively. The laser frequency was 20 Hz (with 50% duty-cycle pulses) for depolarizing opsins (ChR2 and ChrimsonR) and 0 Hz for hyperpolarizing opsins (stGtACR2 and eNpHR3.0). The peak laser power at the tip of the fibre was ~2 mW. Using a Pulse Pal pulse generator (Open Ephys), each laser pulse for stimulating stGtACR2 was initiated and followed by a linear ramp-up and ramp-down of 500 ms, respectively. Stimulation of other opsins was done by square pulses.

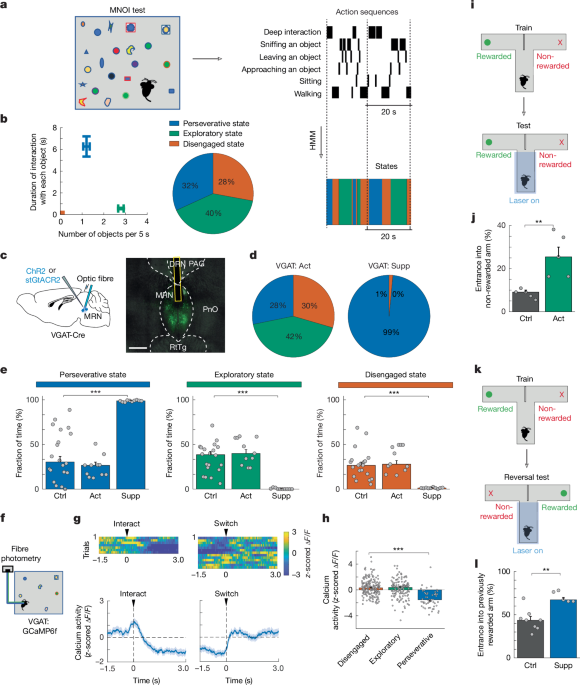

MNOI test

Mice were habituated to the experimenters and the experimental box (40 cm × 40 cm × 50 cm) every day for 3 weeks. For the last three days before the experiment, mice were also habituated to one novel object in the box to minimize stress in response to novel objects. MNOI tests were designed in a free-access manner. Mice were placed in the box for 15 min before the experiment. Then 20 novel objects (with different shapes, colours, textures and materials) were placed in random locations, and mice were allowed to interact with the objects for 2 min with optogenetic laser stimulation throughout the test duration (alternating periods of laser on 4.7 s and laser off 0.3 s). All objects were small (length between 0.5–1.0 cm) and light enough for the mice to be able to pick up and displace. Behaviour was recorded on video using one camera from the top, fixed to the ceiling of the box, and two side cameras (Raspberry Pi cameras (V2 module) with a frame rate of 25 fps).

Videos were labelled frame by frame using JAABA57. Analysers were blind to the experimental groups of mice. Behaviours displayed during object interaction were categorized as approaching: turning of the head towards the object accompanied by a body movement decreasing the distance between the mouse and the object; approaches ended when the mouse was at 0.5 cm distance to the object; shallow interaction: location within whisking distance of the object (closer than 0.5 cm) and facing and seemingly ‘focusing on’ the object for at least 5 frames, this can include touching the object with the snout, but not biting it; deep interaction: at least 1 of the following actions are taken: biting (taking hold of the object between its jaws and/or making nibbling motions with its head, but not walking around with the object), grabbing (holding of the object between the front paws, or standing over the object and blocking the object, effectively preventing it from moving away), and/or carrying (holding the object in its mouth and simultaneously walking around the box with it, effectively displacing the object); leaving the object: moving away from an object after shallow or deep interaction (until the nose is turned 0.5 cm away from the object). Each of these actions was attributed to one of the 20 objects. JAABA labels were imported to MATLAB for further analysis. After extracting mouse positions and movement speed, using custom-made scripts in MATLAB, times that the mouse was not performing the above actions (approaching, sniffing, deep interaction and leaving) were attributed to sitting or walking (binarizing at movement speed of 0.05 cm s−1). To evaluate the effect of phasic optogenetic stimulation of the MRN cell types on interaction with the novel objects, we used a 2-min MNOI test with only 5 spaced-apart novel objects. Two-second laser stimulation was applied roughly 50% of times in 1 of 3 conditions: when the mouse was not interacting with any object (at least 2 cm away from any objects or not heading towards objects), when it was within whisking distance of an object and facing the object (snout closer than 0.5 cm), and when it initiated a deep interaction with an object (biting, grabbing or carrying). The probability to switch to another object, transition probability to brief interaction (sniffing or facing towards the object within whisking distance), to deep interaction, and to no interaction, within 2 s from laser onset, was quantified as the phasic effect of laser stimulation.

Hidden Markov model

We used a HMM58 to extract states that may underlie different sequences of actions. The HMM requires an estimated transition matrix, an estimated emission matrix and a sequence as input. The sequence was generated from the data of assigned mouse behaviours during the multi object interaction test. We created a non-overlapping sequence vector, with just one action happening at each time. This was achieved by creating a ranking sequence in which non-object-interacting behaviour (sitting and walking) was the lowest, then leaving, approaching, sniffing and deep interacting was the highest rank, and the highest rank was chosen as current action. We assumed that the higher the rank was, the more important information it conveyed of the mice’s state for investigatory behaviour. We set the model to three states, because we hypothesized three underlying states important for object interactions, a perseverative state in which mice persist in interacting with the current object, an exploratory state in which mice switch between multiple objects with short interactions, and a disengaged state without object interactions. As we did not have a priori information on the transitions between the states, our starting estimate for the transition matrix contained equal probabilities for all transitions, but starting with a random transition matrix did not change the results. We generated the initial estimated emission matrix by predicting the likelihood of a behaviour present in a certain state. Using a Baum-Welch algorithm59, we trained the model on control mice to estimate the transition and emission probabilities for the HMM (Fig. 1b). Setting the model to 4 states yielded similar results—that is, a perseverative state (mainly consisting of deep interaction), an exploratory state (mainly consisting of shallow interactions, approaching and leaving of multiple objects, with probabilities of 0.71, 0.16 and 0.11, respectively), and 2 states without object interactions. As this test was focused on object interactions, we thus chose to use the 3-state HMM. For all other groups of mice (including mice used for optogenetic and photometry experiments), the states’ probabilities at each time bin (bin size 0.5 s) were decoded from their vectors of rank-number actions based on the emission and transition matrices trained on control mice. Finally, each time bin was attributed to the state with maximum likelihood, resulting in a sequence of states. We used the built-in HMM functions hmmtrain and hmmdecode in MATLAB to acquire and evaluate the transition and emission matrices for control mice and estimate the states’ probabilities for other mice. To estimate the conditional transition probability between different states in Extended Data Fig. 1h, one time bin was used for the duration of each state, such that transition probabilities were only calculated for time points of state changes.

Real-time place preference test

Mice with expression of an optogenetic opsin (ChR2, stGtACR2 or eNpHR3.0) or tdTomato (control) underwent a real-time place preference test in a custom-made two-chamber acrylic box (60 cm × 30 cm × 30 cm (l × w × h)). After 10 min of habituation to the box, one of the two chambers was paired with laser stimulation (triggered by entering the chamber). The laser-coupled chamber was randomly assigned. The total test duration was 10 min. Mouse behaviour was analysed using Bonsai software (https://bonsai-rx.org/). Using a custom-made MATLAB script, the preference for the opto-linked chamber was calculated as follows: 100% × (duration of time spent in the opto-linked chamber − duration of time spent in the non-stimulation chamber)/total time).

Self-stimulation test

Mice with expression of an optogenetic opsin (ChR2, stGtACR2 or eNpHR3.0) or tdTomato (control) were habituated for 1 h to a custom-made experimental box (40 cm × 40 cm × 50 cm; l × w × h) with a two-port nose-poke system one day before the test. During the habituation period, drops of 10% sucrose water were delivered through both ports to habituate the mice to the nose-poke ports. No sucrose water was delivered during the test. Instead, an infrared sensor in only one nose-poke port triggered optogenetic stimulation when the mouse entered the port with its nose, and stimulation continued throughout the time period the mouse’s nose remained in the nose-poke port. An infrared sensor in the other nose-poke port did not trigger any stimulation. The test lasted 1 h. The number of returns to each port was detected by the sensors (connected to an Arduino UNO microcontroller board) and preference for returning to the opto-linked nose-poke port was calculated as follows: 100% × (number entries into the opto-linked nose-poke port − number of entries into the non-stimulation nose-poke port)/(number of entries into the opto-linked nose-poke port + number of entries into the non-stimulation nose-poke port). The length of time mice spent with their snout in a port was not taken into account for this analysis.

T-maze tests

To measure the effects of optogenetic stimulation on exploratory versus perseverative choices based on acquired choice-outcome knowledge, we trained food-restricted mice on a T-maze task60,61, in which a food reward (10 mg of their preferred food, yoghurt drop or their regular food (Teklad Global 2016; 16% protein, 4% fat)) was provided consistently only in one specific arm and not the other. Training started after 2 days of 15-min habituation to the T-maze, to the experimenter and to a soft towel by which they were placed in and picked up from the T-maze. Each training trial started with placement of the mouse at the start of the central arm and ended with the mouse turning into either of the choice arms (left or right). At the end of each trial the entrance of the choice arms was blocked to prevent the mouse from returning to the other arms. After reaching the end of the non-rewarded arm or after eating the food reward at the end of the rewarded arm, mice were gently picked up in the soft towel and placed back at the start of the central arm. After mice achieved more than 90% correct trials in two sequential 50-trial sessions (well-trained; mean ± s.d.: 7.42 ± 2.66 sessions), they entered one of the two tests. For behaviour sessions with optogenetic manipulations (55 trials), optogenetic stimulation was delivered in the central arm of the T-maze until after mice chose one of the arms. In these sessions, food reward was either provided in the same arm as during training, in which case the percentage of trials in which they entered the non-rewarded arm indicated their tendency to explore, or the reward location in the T-maze was reversed—that is, the previously rewarded arm was not rewarded anymore. In this second scenario, normally mice start exploring the other, previously non-rewarded arm and eventually learn to expect reward only at this location. The percentage of trials in which they entered the previously rewarded arm (that is, the currently non-rewarded arm) indicated their tendency to persevere in the previously rewarded choice.

Nose poke–reward association task

To measure the effect of optogenetic stimulation on task engagement, we used a previously described nose poke–reward association task62. After three days of water restriction, mice with expression of an optogenetic opsin (ChR2, stGtACR2 or eNpHR3.0) or tdTomato (control) were trained to enter their nose into a nose-poke port on one wall of a custom-made operant chamber (25 cm × 20 cm × 30 cm (l × w × h); in a sound-attenuating box) in order to receive a water reward from a lick spout on the wall opposite to the nose-poke port. At the start of each trial, the nose-poke port was illuminated. Upon completion of a successful nose-poke, the light in the nose-poke port was turned off, and a white noise sound was turned on to indicate the availability of reward. A water reward was delivered to the lick spout, via a solenoid valve, upon licking. A nose-poke entry followed by a lick was considered a single completed trial. Mice were free to run back and forth between the nose-poke port and the reward spout and complete trials at their own pace. Training continued daily until mice were able to complete more than 85 trials per session in two sequential daily 30-min sessions (mean ± s.d.: 10.40 ± 4.35 sessions). Following training, mice performed the same task during which they received 3 epochs of 2-min optogenetic stimulation with random off-stimulation time intervals (not less than 2 min) between 2 min and 20 min from the session’s onset. The number of completed trials indicated the engagement level. Data acquisition and stimulation was performed using a Pycontrol state machine (https://pycontrol.readthedocs.io/en/latest/).

Nose poke–reward association task with distractor nose-poke ports

To measure the effect of optogenetic stimulation on evoking exploration, we modified the nose poke–reward association task, by adding two nose-poke ports without function at the side walls. Following training in the standard nose poke–reward association task, mice with expression of ChR2 in VGluT2+ or VGAT+ neurons in MRN, or tdTomato (control) mice were tested in the presence of the two additional nose-poke ports, used as distractors to motivate exploration. Only an entry into the previously learned nose-poke port followed by a lick from the lick spout resulted in water-reward delivery. At the beginning of the test, mice were given a 5-min period to explore all the nose-poke ports and understand that the additional nose-poke ports are not associated with reward. During the following 20 min, mice received optogenetic stimulation (for a random time period between 1 and 2 s) in 25–35% of trials upon entering into a 0.5 cm radius around the reward-associated nose-poke port. From laser onset until completion of the trial (receiving a water reward), the number of times mice interacted with the distractor nose-poke ports or the lick spout (without initiating the trial) was counted as number of interactions with distractors in this trial. Data acquisition and stimulation was performed using a Pycontrol state machine and data analysis was performed by a custom-made MATLAB script.

Three-armed bandit task

To measure the effect of optogenetic manipulation of MRNVGluT2 and MRNVGAT neurons more specifically on the trade-off between exploration and exploitation, we used a 3-armed bandit task with 3 water lick ports, P1–3, on 3 walls of a custom-made pentagon-shaped operant chamber. Reward probability at P3 was constant at 50%, and reward probabilities at P1 and P2 fluctuated in blocks (25–35 trials), between 10% and 90% (for VGluT2 neuron activation) or between 25% and 75% (for VGAT neuron suppression). Each trial was self-initiated by licking any of the three lick ports, followed by a water reward or no-reward upon licking, and a 2-s inter-trial-interval.

Mice were trained daily until they had learned to switch between the high-probability ports—that is, chose the changing high-probability port in more than 85% of trials for 90%/10% reward probabilities, or in more than 70% of trials for 75%/25% reward probabilities in each block (within the first 20 min, when mice were more engaged) during two consecutive 30-min sessions. Following training, mice performed several sessions of the same task with and without laser stimulation. During the laser stimulation sessions, in 2-3 blocks (within the first 20 min), mice received one epoch of optogenetic stimulation. For VGAT suppression, laser stimulation started after the first 3 consecutive trials of the mouse choosing the new high-probability port after the start of the block. The laser was on until the end of the current block. For VGluT2 activation, laser stimulation started after the 5 consecutive trials of the mouse choosing the new high-probability port after the start of the block, and lasted for 2 s. Behaviour in the interspersed sessions without optogenetic manipulations was used as control data. Data acquisition and stimulation was performed using a Pycontrol state machine and data analysis was performed by a custom-made MATLAB script.

TMT aversion test

Mice were habituated to the experimenter for three days, 30 min a day, and to the experimental box (40 cm × 40 cm × 50 cm (l × w × h)) for 30 min the day prior to the experiment. For the test, mice were habituated in the box for 15 min, after which a small object covered with 3 µl trimethylthiazoline (TMT, BioSRQ: purity >90.0%), a constituent of fox urine, was placed inside the box for 2 min. Optogenetic stimulation was applied for the 2-min duration, with repeated pulse trains of 4.7 s laser on and 0.3 s laser off (to avoid overstimulation of neurons and tissue damage by heat accumulation). Mouse behaviour was recorded (on video (Raspberry Pi camera (V2 module); with 25 fps) and videos were labelled frame by frame using JAABA1. Analysers were blind to the experimental groups of mice. Behaviours displayed during the test were categorized as: approaching (approaching towards the object, from start of body movement until reaching proximity of 0.5 cm), interacting (sniffing, grabbing, carrying or biting the object) and retreating (moving away, upon reaching the object, in the opposite direction to the approach). JAABA labels were imported to MATLAB for further analysis. In addition, mouse position and movement speed were extracted using custom-made MATLAB scripts. A retreat upon reaching the TMT object was counted as an escape if the average speed of the retreat exceeded 0.5 cm s−1 within the first 1 s. Varying the speed threshold (0.3, 0.4, 0.5 or 0.6 cm s−1) did not influence the results. Escape probability was calculated as the number of approaches leading to escape divided by the total number of approaches.

Visually evoked fear response test

Mice with expression of ChR2 in VGluT2+ MRN neurons underwent a visually evoked fear response test to see whether activation of these neurons changes their fear response to an innately threatening visual stimulus, an overhead expanding—that is, looming—black disc63. Experiments assessing escape behaviour in response to looming stimuli were performed in a custom-made transparent acrylic arena (80 cm × 26 cm × 40 cm (l × w × h)) with a red-tinted acrylic shelter (14 cm × 14 cm × 14 cm (l × w × h)) placed on one end (safe zone) and overhead looming stimuli presented on the other end (threat zone)64,65. The arena was placed in a large light-proofed and sound-attenuating box with a near-IR GigE camera (acA1300-60 gmNIR, Basler; with a frame rate of 50 fps) fixed on the ceiling to video record the behaviour. To display looming stimuli, a projector (HF85JA, LG) was mounted in the box and back-projected via a mirror onto a suspended horizontal screen (60 cm above arena floor, 100 cm × 80 cm; ‘100 micron drafting film’, Elmstock). The screen was kept at a constant background luminance level of 9 cd m−2. The arena was illuminated by four infrared LEDs to ease tracking of the mice. Video recording and optogenetics laser stimulations were triggered through Bonsai (https://bonsai-rx.org/). Mice were placed in the arena 20 min before the test to habituate to the new environment. Stimulation was triggered manually by a keyboard when the mouse reached the threat zone. The stimulus was only triggered when the mouse was facing and walking toward the threat zone, with an inter-stimulus interval of at least 2 min. Each visual stimulation consisted of three consecutive looming stimuli (expanding black spot at a linear rate of 55° s−1) in a 3-s period. Visual stimuli of 10%, 50% and 90% contrasts were presented in a randomized order. Laser and non-laser trials of the same stimulus contrast were always presented as paired trials, in a randomized but consecutive order (10 repetitions × 3 contrasts × 2 laser conditions). Optogenetic stimulation in laser trials started 0.5 s before the visual stimulus. Position and running speed of the centre of the mouse were processed using a custom-made MATLAB script. A successful escape was defined as a return to the shelter with an average running speed higher than 0.4 cm s−1 (varying this threshold to 0.3 or 0.5 cm s−1 did not change the significance of the results) in the 2 s after the stimulus onset and reaching the shelter within 5 s of stimulus onset.

Sucrose preference test

The sucrose preference test is frequently used to measure anhedonia in mice based on a two-bottle choice paradigm66,67. A decreased responsiveness to rewarding sucrose compared to a control group indicates anhedonia. On the first day of habituation, mice with expression of ChR2 in LHb input to MRN and control mice were provided with 2 identical bottles of water and on the second day with 2 identical bottles of 1% sucrose water for 24 h, respectively. During the next 4 days, mice were provided with 2 bottles of water, while they were receiving repeated optogenetic stimulation for 24 h (60 s laser on, every 240 s). The next day, after 12 h of water deprivation, mice were tested with 1 bottle of water and 1 bottle of 1% sucrose water (for 12 h), without optogenetic stimulation. Sucrose preference was calculated by the percentage of sucrose water consumed relative to the total liquid consumption.

Arousal level measures and analysis

For these experiments, mice were habituated for three days (30 min a day) to be head-fixed on a styrofoam running wheel (16 cm diameter, 12 cm width) in a sound-attenuating box with dim ambient light. Mice with expression of an optogenetic opsin (ChR2, stGtACR2 or eNpHR3.0) or tdTomato (controls) were used for measuring changes in physiological arousal level caused by optogenetic stimulation. Mice were head-fixed and an infrared LED light was directed to the face to illuminate the pupil (mounted 50 cm away). Their running speed was recorded using a rotary encoder (Kubler Encoder 1000 ppr) coupled to the wheel axle. Mice received optogenetic stimulation for 3-s periods (30 trials with 12-s intervals). The effect of optogenetic stimulation on the arousal level was monitored by recording videos of the pupil and whiskers (using two cameras (22BUC03, ImagingSource) with frame rates of 30 fps), as well as the running speed. Whisker activity during each frame was calculated as the absolute difference between the colour intensity of each pixel of this frame and the previous frame, averaged over all pixels. Baseline z-scored pupil size, whisker activity and running speed were determined using custom-made scripts in MATLAB.

Calcium photometry recordings and data analysis

Mice were habituated to the experimenters for three days (30 min a day) and to the experimental box (40 cm × 40 cm × 40 cm) for three more days (15 min a day). Three weeks after the GCaMP6 viral injection and the optic fibre implantation, calcium activity of MRN neurons, LHb axons or LHAVGAT axons in MRN was recorded in freely moving mice. Recording from MRNSERT neurons was performed in three different conditions, in the presence of multiple novel objects, of food pellets, or of TMT objects. Recordings from MRNVGAT neurons, MRNVGluT2 neurons, LHb axons in MRN and LHAVGAT axons in MRN were done in the presence of multiple novel objects. Movies of mouse behaviour and fluorescence were recorded simultaneously using Raspberry Pi cameras (V2 module, frame rate: 25 fps) and a fibre photometry system (optics from Doric Lenses; acquisition board and recording software from PyPhotometry (https://pyphotometry.readthedocs.io/en/latest); sampling rate: 130 Hz), respectively. Excitation lights at the tip of the optic fibre were adjusted to around 30 µW. The data for fibre photometry were analysed using a custom-made MATLAB program. A linear drift correction was applied to raw signals of calcium-dependent (GCaMP excited at 473 nm) and isosbestic fluorescence (GCaMP excited with 405 nm light) to correct for slow changes such as photobleaching. To correct for non-calcium-dependent signals and artifacts, the isosbestic fluorescence trace was linearly fitted to the calcium-dependent GCaMP fluorescent signal and subtracted, providing a measure of relative transient changes in fluorescence (dF/F). Mean baseline was taken as the average dF/F signal of the entire recording session. Subsequently, z-scored dF/F was calculated by subtracting the mean baseline and dividing by the standard deviation of the baseline distribution. Behaviours were analysed using JAABA and MATLAB, similar to experiments with optogenetic stimulation. Data points in Figs. 1g and 2e are z-scored dF/F values averaged over 3 s after the onset of behaviours stated in the figure legends. Data points in bar graphs in Figs. 1h and 2f are z-scored dF/F values averaged over the time course of the associated interaction states.

Electrophysiological recordings and data analysis

To compare the effect of optogenetic activation of LHb and LHAVGAT inputs to MRN on MRN and VTA neurons, we performed acute electrophysiological single-unit recordings from head-fixed mice while activating the MRN inputs. To this end, we expressed ChR2 in LHb (in 3 C57BL/6 mice) or LHAVGAT neurons (in 3 VGAT-Cre mice), cemented a metal head plate and implanted a fibre above the MRN (as described above). Around three weeks after surgery, mice were habituated to the head-fixation and electrophysiology setup for 3 days, before one acute recording session. A high-density electrophysiology probe (Neuropixels 1.0 prototype 3 A) was inserted to record from MRN (AP: 4.4 mm, ML: 0.1 mm) and posterior VTA (AP: 3.6 mm, ML: 0.5 mm) (through craniotomies above them and based on the distance from the surface of the brain; MRN depth: 3.8–4.8 mm and VTA depth: 3.9–4.6 mm). Prior to insertion, the probe was coated with DiI (1 mM in isopropanol, Invitrogen) for post hoc histological alignment. The probe was inserted using a micromanipulator (Sensapex). Using a Pulse Pal pulse generator (Open Ephys) a train of 100–200 laser pulses of 10 ms for activation of LHb input to MRN or 100 ms for activation of LHAVGAT input to MRN with random inter-stimulus-intervals was used, while recording from the MRN or VTA. Data were acquired using spikeGLX (https://github.com/billkarsh/SpikeGLX, Janelia Research Campus), high-pass filtered (300 Hz) and sampled at 30 kHz.

Spikes were sorted with Kilosort2 (https://github.com/cortex-lab/Kilosort) and Phy68. Each unit was attributed to the channel with the highest waveform amplitude. A single unit was considered to have a robust direct input from LHb if more than 90% of laser pulses resulted in an increase in its firing rate within 10 ms from the laser onset (compared to its firing rate in a 100 ms time window before the laser onset). A single unit was considered to have a robust direct inhibitory input from LHA, if more than 90% of laser pulses resulted in a decrease in its firing rate within 100 ms from the laser onset (compared to its firing rate in a 100 ms time window before the laser onset).

Multi-colour single-molecule mRNA in situ hybridization

In situ hybridization was performed using RNAscope technology. To quantify the overlap between MRN cell types (for Extended Data Fig. 1a,b), we used C57BL/6 mice. To evaluate specificity of Cre expression in MRN of SERT-Cre mice (for Extended Data Fig. 1c–e) we expressed eGFP in Cre-expressing MRN cells through injection of AAV-syn-flox-eGFP into the MRN two weeks before brain extraction). After induction of deep anaesthesia by isoflurane (5%), brains were extracted and immediately fresh-frozen in optimal cutting temperature (OCT). Using a cryostat, brains were sliced into 15-µm sections, mounted on glass slides, and stored at −80 °C. Multi-fluorescence mRNA in situ hybridization was performed using ACDBio RNAscope multiplex fluorescence V2 assay (https://acdbio.com/rnascope-multiplex-fluorescent-v2-assay). The RNAscope protocol was carried out as indicated in the user manual of the ACDBio RNAscope. Brain sections of the MRN were post-fixed with 4% chilled paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS for 60 min and then dehydrated through 4 dehydration steps in 50%, 70%, 100% and 100% ethanol, respectively, at room temperature. After air drying for 10 min at room temperature, Protease IV was applied to the slices for 15 min at room temperature. Then, they were washed out three times by rinsing in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). VGluT2-C1 (1170921-C1), SERT-C2 (315851-C2) and VGAT-C3 (319191-C3) (for Extended Data Fig. 1a,b) or SERT-C2 (315851-C2) and eGFP-C3 (538851-C3) (for Extended Data Fig. 1c–e) were pipetted onto each slice. Probe hybridization took place in an oven set to 40 °C for 2 h, and then, slices were rinsed in 1× wash buffer. After amplification and fluorophore labelling steps, slices were mounted with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) vector shield. Immediately after mounting, the stained slices were imaged by confocal SP8 microscope (Leica) using a 20× objective. For quantification of numbers of labelled and co-labelled cells we used ImageJ (Fiji).

Histology and microscopy

For determining inputs and outputs of specific brain areas, and for histological confirmation of injection sites and fibre locations, at the end of experiments mice were euthanized by an overdose of pentobarbital (intraperitoneal injection, 80 mg kg−1) and transcardially perfused (0.01 M PBS, followed by 4% PFA in PBS). After extraction, brains were post-fixed by 4% PFA solution overnight and consequently embedded in 5% agarose (A9539, Sigma). Imaging was performed using a custom-built automated serial-section two-photon microscope55,56. Coronal slices were cut at a thickness of 40 μm, and images were acquired from 2–8 optical planes (every 5–20 μm) with approximately 2.3 μm per pixel resolution. Scanning and image acquisition were controlled by ScanImage69 v5.5 (Vidrio Technologies) using a custom software wrapper for defining the imaging parameters (https://zenodo.org/record/3631609). Cell detection and counting was performed using Cellfinder (https://github.com/brainglobe/cellfinder). Post hoc histological alignment of the DiI-coated electrophysiology probes was performed by registering 3D images of brains to a reference brain atlas (https://mouse.brain-map.org/static/atlas) using Brainreg (https://brainglobe.info/documentation/brainreg/).

Overall experimental design and analysis

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample sizes, but our sample sizes were determined based on previous studies70,71. The order of mice in different experimental groups was randomly assigned. Experimenters were not blind to the experimental conditions, but the collected data were encoded blindly and analysers were blind to experimental condition. All data were analysed using JAABA, MATLAB, Python and Bonsai.

Statistical analysis

Data are represented as median ± bootstrap standard error, unless stated otherwise. All statistical analyses were performed using InVivoTools MATLAB toolbox72,73,74 (https://github.com/heimel/InVivoTools) or custom-made MATLAB scripts. First, normality of the data distribution was tested, using a Shapiro–Wilk normality test. To assess group statistical significance, if data were normally distributed we used parametric tests (t-test and paired t-test for non-paired and paired comparisons, respectively), and otherwise non-parametric tests (Mann–Whitney U-test and Wilcoxon signed-rank test for non-paired and paired comparisons, respectively), followed by a Bonferroni P value correction for multi group comparisons. For multi group comparisons with subgroups within groups we used nested one-way ANOVA. To evaluate optogenetic effect over multiple trials in the 3-armed bandit task we used 2-way repeated measures ANOVA. To statistically compare distributions of discrete data across different groups, chi-square test was used. Individual data points are shown in the figures. Statistics used in the main figures are listed in Extended Data Table 1 and statistics in Extended Data figures are listed in the figure legends.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.