Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every day? Sign up here.

Engineers prepare to add a KM3NeT module to the network of sea-floor detectors. Credit: Paschal Coyle/CNRS

Astrophysicists have observed the most energetic neutrino ever. The particle — which probably came from a distant galaxy — was spotted by the Cubic Kilometre Neutrino Telescope (KM3NeT) anchored to the floor of the Mediterranean Sea. KM3NeT picks up light emitted by high-energy, electrically charged particles such as muons — which can be produced when high-energy neutrinos smash into Earth’s atmosphere. In early 2023, it detected a muon that carried approximately 120 petaelectronvolts of energy. From the particle’s energy and its near-horizontal trajectory, researchers concluded that it was probably produced by a neutrino more than 20 times more energetic than any seen before.

Researchers have developed a cheap, simple blood test to detect pancreatic cancer before it spreads to other areas of the body, when treatment is more likely to be successful. The test uses a nanosensor to detect enzymes called proteases, which break down proteins and are active in tumours, even from the very early stages. Tests on frozen blood samples showed the test identified people with pancreatic cancer with a 73% accuracy, which is “a very promising, very impressive result”, says biomedical engineer Simone Schürle-Finke.

Reference: Science Translational Medicine paper

High living costs, low stipends and limited job options after graduation are all seemingly behind a drop in the number of people enrolling PhD programmes in some countries. The declining numbers signal that countries “need to reform working conditions and think about diversifying career options”, or risk a talent drain, says policy analyst Cláudia Sarrico. Another problem is the public perception that PhD students only research “esoteric questions that are unrelated to the social good of our community”, says Louise Sharpe, president of the Australian Council of Graduate Research.

Researchers in Norway have mounted a legal challenge to the introduction of mandatory Norwegian language classes for foreign PhD students and postdocs, arguing that the requirement violates labour laws and threatens to harm the country’s ability to compete internationally in research. “Our principal investigators, postdocs and PhDs come from all over the world,” says neuroscientist and Nobel Laureate Edvard Moser. “These demands will make it difficult for us to recruit them.” Advocates of the law argue it will preserve Norwegian as a professional language, countering the increasing use of English in higher education.

Features & opinion

More than 150 scientists have contributed to a report that was weeks from completion when it was cancelled by an executive order from US president Donald Trump. But they are determined to finish the job, a first-of-its-kind assessment of nature across the United States, on their own. “This work is too important to die,” wrote the project’s director, environmental scientist Phil Levin, in an e-mail to colleagues on the day of the cancellation. “The country needs what we are producing.”

The New York Times | 6 min read

How is your research faring under the new US presidential administration? We’d love to hear what you have to say — please contact our news team via this page on nature.com.

The reluctance of Japanese funding agencies to award grants to cross-disciplinary research risks eroding the country’s global standing in science and its economy, says a group of Japanese scientists. They argue that agencies should fund curiosity-driven, interdisciplinary research with long-term goals and understand that ‘unsuccessful’ projects can still generate valuable knowledge. To facilitate this shift, grant panels must be more diverse, in scientific discipline, gender and other metrics, and funds should be awarded on a flexible, multi-year basis. “Nothing is stopping Japan from adopting a bolder funding model,” the group writes. “Innovative projects and outcomes should soon follow.”

In 2010, biochemist Felisa Wolfe-Simon announced the discovery of a bacterium that could use arsenic in place of phosphorus in its biological molecules, including its DNA — which quickly became known as #arseniclife. A few days later, the research community began to criticize the research on their blogs and social media, taking peer review into the public realm in a way rarely seen before. Amid the critiques, which quickly turned personal, Wolfe-Simon found herself unable to get grants or publish, and she left research. Now, as Science considers retracting the original paper, she’s back, studying bacteria that create magnetic crystals within their membranes.

The New York Times | 12 min read

Reference: Science paper (from 2010)

Image of the week

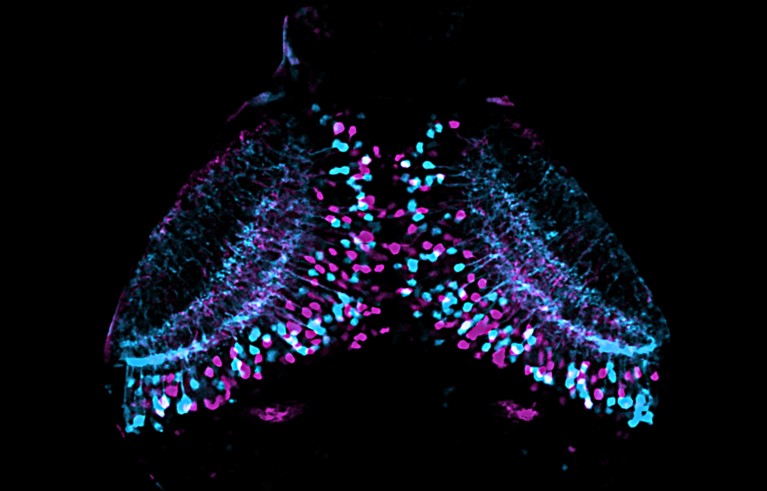

Figure 1 | Neurons in the zebrafish (Danio rerio) brain. Shainer et al.1 classified neurons of the optic tectum, a visual-processing centre, into ‘transcriptomic-types’ (t-types) on the basis of the RNA transcripts that they express. The authors show that t-type does not always reflect a neuron’s classification on the basis of its function or morphology (shape), but that it does relate to the neuron’s position in the tectum. The fluorescent labelling shows two distinct t-types. (Adapted from Fig. 6 of ref. 1.)Credit: I. Shainer et al./Nature

Researchers analysed neurons (shown here fluorescently labelled) in a visual-processing centre of the brains of zebrafish (Danio rerio) called the optic tectum, and classified cells into transcriptional ‘types’ (t-types) based on the RNA they expressed. They found that some cells could have the same t-type, meaning they were genetically similar, but have different functions and shapes. T-type did however relate to the neuron’s position in the tectum. (Nature News & Views | 7 min read, Nature paywall)

Today I’m reassured that artificial intelligence (AI) isn’t going to put me out of a job. The BBC put chatbots such as Open AI’s ChatGPT to the test by showing them 100 news articles and then asking questions about them. In more than 50% of cases, the answers contained “significant inaccuracies”, testers concluded. I might make a mistake every once in a while, but I’m confident my error rate is lower than that.

Rest assured, however, that even if AI could accurately summarize the news, Nature Briefing will always be written by humans.

Help us avoid inaccuracies by sending any feedback to [email protected].

Thanks for reading,

Jacob Smith, associate editor, Nature Briefing

With contributions by Flora Graham & Gemma Conroy

Want more? Sign up to our other free Nature Briefing newsletters:

• Nature Briefing: Careers — insights, advice and award-winning journalism to help you optimize your working life

• Nature Briefing: Microbiology — the most abundant living entities on our planet — microorganisms — and the role they play in health, the environment and food systems

• Nature Briefing: Anthropocene — climate change, biodiversity, sustainability and geoengineering

• Nature Briefing: AI & Robotics — 100% written by humans, of course

• Nature Briefing: Cancer — a weekly newsletter written with cancer researchers in mind

• Nature Briefing: Translational Research — covers biotechnology, drug discovery and pharma