For people with moderate to severe psoriasis, highly targeted antibody-based treatments introduced in the past 10–15 years have been life changing. Inflamed skin covering swathes of the body often resolves completely. “It’s difficult to find a non-responder to these therapies, says Curdin Conrad, a clinical dermatologist and psoriasis researcher at Lausanne University Hospital in Switzerland.

Nature Outlook: Skin

But these antibody therapies, which selectively take out the inflammatory molecules that drive the disease, have a major drawback: they must be taken for life. If treatment stops, the disease comes roaring back.

At least, that’s what usually happens. Some people with psoriasis can stop taking antibody treatment and not have a relapse. Conrad says that one of his patients who had been taking the antibody drug had to pause it in preparation for a dental operation — and that “six years later, she was still completely disease-free, not a single lesion”.

As large clinical trials test this phenomenon, and researchers further unravel the underlying molecular mechanisms of psoriasis, excitement is growing that new treatments for this disease could be much more durable.

Cascade biochemistry

Psoriasis affects at least 100 million people worldwide, and it is currently deemed to have no cure1. The most visible symptom of this chronic non-communicable disease is the presence of painful, inflamed skin lesions, called plaques, that are colonized by overactive immune cells. Yet the inflammatory damage of psoriasis goes deeper. People with psoriasis are at high risk of developing cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and arthritis. The impaired quality of life and stigmatization can take a toll on mental health.

The biomolecular trigger that initiates the over-activation of immune cells in affected skin remains a mystery, says Asolina Braun at Monash University in Clayton, Australia, who studies this first phase of the disease. “It’s hard to catch that moment at the very beginning, so we still don’t know what starts it,” she says. But by comparing psoriatic and healthy skin, a clear picture has emerged of the cascade of inflammatory signalling molecules, or cytokines, driving the condition. And promisingly, Braun says, “we now know how to control this cytokine cascade”.

Antibody therapies target one of three key cytokines: tumour necrosis factor α (TNF-α); interleukin 17 (IL-17); or interleukin 23 (IL-23). Blocking any of these shuts down the inflammation in affected skin. The leading antibody therapies for psoriasis include secukinumab by Novartis in Basel, Switzerland, which targets IL-17, and guselkumab from Johnson & Johnson in New Brunswick, New Jersey, which targets IL-23.

On trial

Although psoriasis antibody treatments are safe and effective, taking immune-system modifiers for life poses concerns. Long-term use of these drugs “systemically changes a person’s immune balance”, says Liv Eidsmo, a clinician and psoriasis researcher at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm. For example, blocking TNF-α can increase the risk of non-melanoma skin tumours, and blocking IL-17 can trigger inflammatory bowel disease. “Yet we cannot stop the treatment, so we’re stuck,” Eidsmo says.

To find a way out of this trap, researchers are studying the 10–20% of people with psoriasis whose condition does not relapse for months or even years after stopping treatment. In one trial, researchers gave individuals with moderate to severe psoriasis secukinumab for one year, then stopped the therapy and monitored how quickly their condition relapsed2. The key factor in relapse time was how soon after disease onset they had started treatment. “Patients with a short disease duration, who had started treatment within a year of onset, remained relapse free for a long time,” Conrad says. In those who waited longer to start treatment, the odds of remaining relapse-free gradually tailed off. People with a disease history of five years or more before starting treatment had rapid relapses.

Liv Eidsm is a psoriasis researcher at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm.Credit: Karolinska Institutet

If antibody treatment is given early enough, the results suggest, then lifelong treatment could be avoided. “We now know,” Conrad says, “that we have a window of opportunity to modify the disease, where we can treat the patient to get them into remission — then potentially wean them off the therapy completely”.

Conrad and Eidsmo are both involved in the first psoriasis trial designed to test early intervention followed by treatment withdrawal. The STEPIn study tracked outcomes after one year of secukinumab therapy in people whose psoriasis became severe within 12 months of developing it.

By the end of the first year, more than 90% of people treated had seen a 90% or more reduction in their disease severity and spread3. Treatment was then withdrawn; the outcomes in year two are expected to be known before the end of this year. If a substantial number of people remain disease-free, it could have major ramifications for when this therapy is administered. “If early treatment results in a smaller disease burden, then that could be the way to go,” Eidsmo says.

Meanwhile, the GUIDE trial is investigating tapered dosing after early intervention with the antibody guselkumab. Going after IL-23 seems even more effective than targeting IL17, Conrad says — perhaps because it is higher up the psoriasis inflammatory cascade. Initial GUIDE results have shown that participants whose skin clears completely after early intervention could have their dosing frequency halved4. GUIDE’s final phase will test complete treatment cessation.

Clinical impact

These early intervention trials have already changed psoriasis treatment in the clinic. “For patients who get severe quickly,” Conrad says, “we can give them early access to these drugs.” Early intervention potentially turns their debilitating disease into a mild case that is controllable with occasional topical treatments.

Although clinical trials have focused on moderate to severe psoriasis, people with mild disease — the most common form — could also benefit from early intervention. In a 2022 study led by John Frew, a dermatologist at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia, researchers provided early antibody treatment to people with guttate psoriasis5. This mild form of psoriasis usually resolves quickly, but 30% of people with it progress to chronic plaque psoriasis. “Our study showed that you can intervene early and reduce that risk of progression,” Frew says.

The mechanism by which early intervention reduces the risk of relapse remains unclear. The initial focus has fallen on T cells, a type of immune cell that has long been linked with psoriasis. Usually, T cells patrol the body for specific peptides produced by pathogens. In psoriasis, some T cells mistakenly start reacting to the body’s own peptides — the as-yet-unidentified trigger that Braun is hunting down.

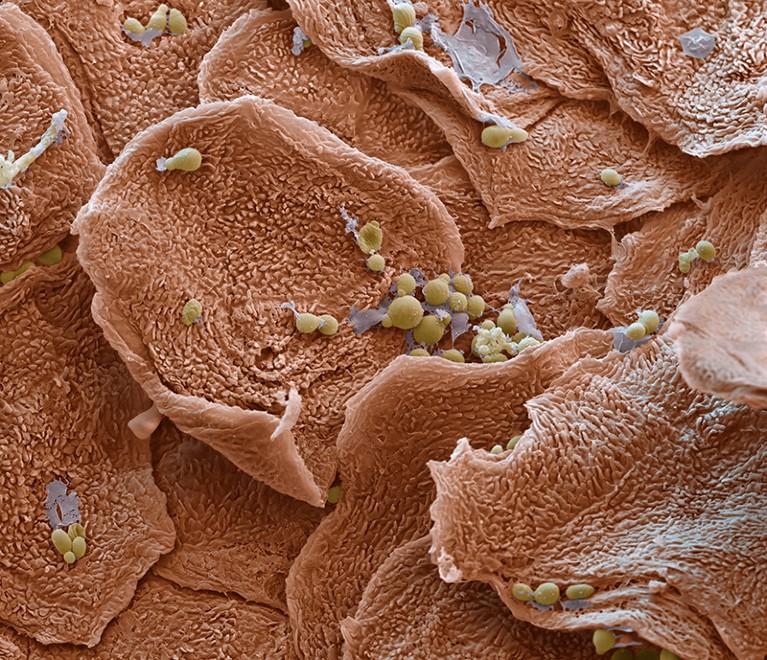

Plaques of dry, scaly skin that are colonized by overactive immune cells are a symptom of psoriasis.Credit: Eye Of Science/Science Photo Library

A type of T cell known as a tissue resident memory T (TRM) cell is permanently stationed in the skin, and is increasingly recognised as the key player in psoriasis. In clinical trials of antibody therapies, “you always see a decrease in these TRM” cells, Conrad says. When treatment stops, levels of TRM cells soar again in people whose disease relapses, and skin plaques return. TRM cells are therefore an obvious psoriasis target. But there’s debate as to whether eliminating them is a good idea because, says Conrad, “the vast majority of TRM [cells] in the skin protect us from pathogens”.

Rather than annihilating TRM cells, Braun hopes that she can rehabilitate the cells by identifying the peptides that aberrant TRM cells are misidentifying as a threat. “Once we know the trigger peptides, we could develop a reverse vaccination that re-educates the immune system that this peptide can be safely ignored,” she explains.

Eidsmo also targets TRM cells, with a focus on the many people with psoriasis who never progress past mild disease and for whom treatment options have barely improved since the 1990s. “I’d like to figure out a way to locally manipulate TRM cells in mild cases,” she says.

Remediating scars

Tackling TRM cells is not the only potential route to psoriasis remission, Conrad says. Rather than T cells — a part of the adaptive immune system — Conrad is focused on innate immunity, a more evolutionary ancient form of defence.

For decades, the general understanding of innate immunity was that, unlike adaptive immunity, it was unable to learn from previous pathogen encounters. But over the past 15 years, this idea has been overturned. Scientists now know that once the innate immune system fights off one invader, it can more effectively fight off a second.

This innate immune memory capability has direct implications for psoriasis. In 2017, researchers studying psoriasis-like skin inflammation in mice showed that immune memory in skin cells called keratinocytes was driving the condition6. The team showed that keratinocytes’ immune memory was based on epigenetic reprogramming — molecular annotations to their DNA that bookmarked stress-response genes, priming their chronic inflammatory behaviour.

More from Nature Outlooks

Epigenetic immune memory plays a key part in psoriasis relapse. “We now know,” says Frew, “that innate epigenetic remnants remain present even after clinical remission of psoriatic disease” after antibody therapy. “Even though you may be completely clear of clinical disease, there’s still some residual inflammatory scar.”

It is this gradual build-up of epigenetic scarring that explains the early treatment window for disease-course modification, Conrad says. “Intervening with antibody therapy early on might be preventing such epigenetic changes, or reversing them,” he says.

Evidence points in that direction, too. In an epigenetic analysis presented at a dermatology conference in 2023, participants of the STEPIn early-intervention trial who had had the disease for less than a year when treatment began saw epigenetic scarring in the form of DNA methylation reversed to normal levels after 12 months. By contrast, people who had had the disease for more than five years had more pronounced epigenetic scarring before treatment, and still had residual scarring after a year of antibody therapy7.

Perhaps, with longer treatment, this scarring might eventually fade. “The next question is, can we add something alongside the antibody therapy that directly effects epigenetic change?” Conrad says. If a second therapeutic can erase these epigenetic bookmarks, it might become possible to stop antibody treatment without triggering a psoriatic flare-up.

With multiple lines of research targeting T cells and innate immune memory, the next decade could transform psoriasis treatment, Conrad says. “Ten years ago, I thought we wouldn’t cure psoriasis in my lifetime,” he says. “Now, I think we’ll be able to cure some patients within the decade.”