Bacterial strains and plasmids

All strains, plasmids, oligonucleotides and phages used in this study are listed in Supplementary Tables 1–4. Genetic modifications were performed as described previously6. Chromosomal deletions were performed using the λ-Red recombination method; PCR products containing the kanamycin cassette were integrated into bacteria containing pKD46, as described previously42. All deletions were then transduced using phage P2243 lysates and appropriate selection. Curing of phage P22 after transduction was verified by purifying the strains on EBU (Evans-blue uranine) plates to indicate lysis and PCR at the mutation site43. The kanamycin cassette was then removed through recombination at frt (flippase recognition target) sites using FLP (Flippase) recombinase encoded on pCP2042. Unmarked deletions and point mutations were generated through allelic exchange with pTOX2 or pTOX344. In brief, a 2–3 kb fragment including the target mutation was cloned into pTOX plasmids44 at the SwaI site by Gibson Assembly (New England Biolabs). This plasmid was transformed into the auxotrophic MFDλpir strain for conjugation into S. Typhimurium45. Selection for MFDλpir transformants was performed with chloramphenicol and 300 μM meso-diaminopimelic acid. S. Typhimurium was selected on chloramphenicol after conjugation and counter-selection was performed on lysogeny broth plates with 2% rhamnose. All insertions, deletions and substitutions were verified by colony PCR with OneTaq (New England Biolabs) using primers flanking the cassette or by localized sequencing at the mutation site. All other plasmids were constructed using restriction cloning or Gibson Assembly with 2x Gibson Assembly Master mix (New England Biolabs; construction details for each plasmid noted in Supplementary Table 2). All plasmids were verified by sequencing of the insertion (Quintara Biosciences) or the entire plasmid (SNPsaurus). Plasmids that were not transformed into another strain background were maintained in E. coli DH5α.

Prophage curing

Prophages were cured using counter selection with MqsR from pTOX2. In brief, λ-Red recombination was used to insert a portion of the pTOX2 vector including the chloramphenicol resistance gene and rhamnose-inducible MqsR toxin into each prophage. This cassette was transduced into the desired strain using P22 with selection on chloramphenicol. Following curing of P22, the counter selection with 2% rhamnose was performed after brief exposure to 2 mM H2O2 (shown to induce prophages in 14,028 s). Prophage curing was verified by PCR at the att site and whole genome sequencing (SeqCenter).

Prophage lysogenization

To construct lysogens of the temperate prophage ES1846 in strain 14028, concentrated stocks of each phage were spotted onto a lawn of the recipient strain embedded in 0.5% lysogeny broth agar in 12-well culture plates. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 12–16 h. Bacteria from the turbid centre of the region of lysis were purified onto lysogeny broth twice and screened by PCR for the presence of the temperate phage to which they had been exposed.

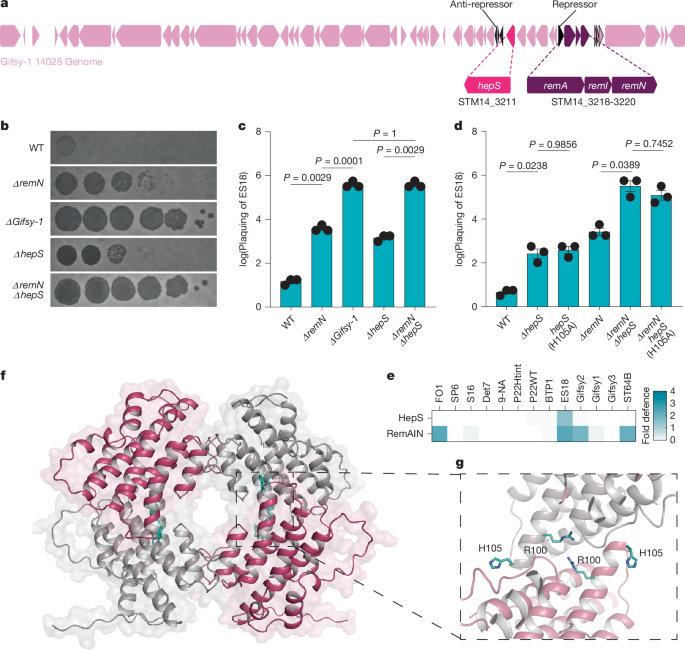

Quantification of phage plaquing and defence

Plaque assays were performed on lysogeny broth with 0.5% top agar as described. Tenfold dilutions of phage stocks were plated on lawns of indicator strains of interest. All plaque assays were performed with stationary phase cultures inoculated from a single colony (16 h). Plaque assays were incubated overnight (12–16 h) before imaging with a BioRad Chemidoc. Where defences prevented the formation of single plaques on some strains, plaquing of phage was scored on the basis of clearance across the tenfold dilution series and the size of plaques. Thus, phage plaquing is reported as the lowest phage tenfold dilution at which clearance was observed and the relative plaque size at the next dilution in 0.25-fold increments. This is a score of plaquing on a log scale. The fold defence, as calculated in Figs. 1e and 2a, is the difference between the score of plaquing in the presence and absence of the hepS gene.

Phage stocks and phage propagation

All phages used in this study are reported in Supplementary Table 4. Lytic phages were propagated on prophage-cured strains of S. Typhimurium. Lysates were collected from phage-infected cultures and treated with chloroform. Temperate phage lysates were generated by inducing prophages from the appropriate lysogens with MMC. The supernatants of MMC-treated cultures were collected 2–4 h after treatment and treated with chloroform. Phage stocks were stored at 4 °C until use. When higher concentrations of phage were needed, lysates were concentrated using Amicon Ultra Centrifugal Filter with a 30 kDa molecular weight cutoff (MWCO).

Phage infection lysis assay

Lysis of bacterial cultures was observed by measuring the optical density of bacterial cultures during phage infection. Bacterial cultures were diluted to an equivalent optical density (0.05 for ES18 and BTP1, 0.1 for FelixO1). Tenfold dilutions of phage were added to wells of a 96-well plate and mixed with 100 µl of diluted bacterial cultures. The plate was incubated at 37 °C with shaking for 6–10 h in a TecanMPlex plate reader. Optical density measurements were recorded in 10- or 15-min intervals. Each assay included technical duplicates for each phage and dilution. To assess defence by HepS, remN was deleted in all strains.

Overexpression of J

Bacteria containing pBAD33 plasmids and derivatives encoding J were grown overnight in lysogeny broth medium containing chloramphenicol and 1% glucose. Subcultures (1:100) were made in fresh lysogeny broth medium containing the appropriate antibiotics and 0.4% arabinose. Growth was measured over 10–16 h in a plate reader (Tecan MPlex). Optical density measurements were recorded in 10- or 15-min intervals. Each assay included technical duplicates for each strain. All experiments in S. Typhimurium were performed in strains in which remN was deleted.

Survival during HepS toxicity

Bacteria containing pBAD33 plasmids and derivatives encoding J were grown overnight in lysogeny broth medium containing chloramphenicol and 1% glucose. Subcultures (1:100) were made in fresh lysogeny broth medium containing the appropriate antibiotics. After 2 h, 0.2% arabinose was added. Bacterial survival was measured by plating serial dilutions of induced cultures on lysogeny broth plates with 2% glucose at the indicated timepoints. All experiments in S. Typhimurium were performed in strains in which remN was deleted.

Observation of prophage-induced lysis

Bacteria were grown overnight in lysogeny broth medium. Subcultures (1:100) were generated in fresh medium and grown for 2 h. At this point, optical density was recorded and MMC (1 μg ml–1) was added to each culture. Optical density was subsequently measured in 1:10 dilutions at 1 or 2 h intervals for 6–8 h. Bacterial survival was measured by plating serial dilutions of induced cultures on lysogeny broth plates with 2% glucose.

Quantification of phage particles during prophage induction

Lysates were prepared by treating supernatants of bacterial cultures with chloroform (5% v/v). Plaque assays were performed in lysogeny broth using the double layer agar overlay method with a lawn of the indicator strain in 0.5% top agar over a 1.5% agar base. Indicator strains were grown to stationary phase in lysogeny broth before the assay. Phage stocks were diluted in a tenfold series in phosphate-buffered saline. Drops (3 μl) of each dilution were plated in duplicate on the top agar. Drops were allowed to dry at room temperature before incubating the plates at 37 °C. Phage plaques were counted after overnight incubation.

Visualization of tRNA cleavage

For samples from HepS activation in cells, total RNA was extracted by phenol or chloroform extraction and precipitation, and run on a 15% AU–PAGE gel. All experiments were performed in S. Typhimurium with remN deleted. For samples from cell-free transcription or translation, PCR templates for cell-free transcription were generated with extended primers, including the T7 promoter and RBS (forward primer) and the T7 terminator (reverse primer) as previously described47 using OneTaq polymerase (New England Biolabs). PCR products were purified and 25–50 ng μl–1 of each template was added to water to supplement the volume where necessary. The cell-free transcription or translation reaction was performed for 2 h at 37 °C according to the manual (New England Biolabs). The RNA was then run directly on 10.8% AU–PAGE gels, and visualized using methylene blue staining overnight. Where indicated, purified HepS protein was added instead of a PCR template.

tRNA sequencing

tRNA sequencing was performed using the same methods used to identify targets of RemAIN6. For samples from cell-free transcription or translation (HepS or HepS+J), RNA was run directly on 10.8% AU–PAGE gels. For samples from bacterial cells (∆remN or ∆remN ∆hepS strains 2 h following induction of J), total RNA was extracted by phenol or chloroform extraction and precipitation, and run on a 15% AU–PAGE gel. tRNA and cleaved tRNA were cut out of AU–PAGE gels, extracted and precipitated with isopropanol before library preparation. Sequencing libraries were constructed as described previously33. In brief, tRNAs were deacylated with alkaline treatment (100 mM Tris, pH 9) and ligated to 5′ adenylated and 3′ end-blocked oligos (linkers_D701-D708) using T4 RNA ligase (New England Biolabs). Ligated tRNAs were gel extracted and reverse transcribed with TGIRT-III (InGex) and the reverse transcription primer. Complementary DNA was gel-extracted and then circularized with CircLigase II (Epicenter) and amplified with Phusion Polymerase (New England Biolabs) with the index_D501 and univ_r primers. PCR products were gel-extracted. Single-end sequencing was performed with a NextSeq sequencer (Illumina). Reads from tRNA-sequencing were analysed using a previously described pipeline33, which included: trimming to remove adaptor sequences; mapping to S. Typhimurium tRNAs that were exported from tRNA-db48 using bowtie v1.2.2 (ref. 49); and tabulation of 5′ read endpoints using samtools v.1.1 (ref. 50) and bedtools v2.27.1 (ref. 51). The frequency of 5′ termination sites from samples in which STM14_3211 was active was normalized to samples in which STM14_3211 was inactive to identify tRNAs that were truncated at an increased frequency during HepS activation. GraphPad prism was used to generate heatmaps of normalized truncation signals. Raw reads are available at NCBI sequence read archive (accession no. PRJNA1257020). Scripts are available on reasonable request.

HepS purification and crystallization

Plasmids for expression of tagged proteins were transformed into BL21 LOBSTR52 cells carrying the pRIL plasmid (KeraFast). For testing of the trigger peptide activation of HepS, subcultures of bacteria (1:100) carrying pMS835 and either pMS1006 or pMS1008 were made in fresh lysogeny borth medium containing the appropriate antibiotics and 1 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside. Growth was measured over 10–16 h in a plate reader (Tecan MPlex). Optical density measurements were recorded in 10- or 15-min intervals. Each assay included technical duplicates for each strain. Proteins were purified based on methods described previously53. In brief, transformed LOBSTR cells were inoculated in 25 ml minimal dextrose glutamate (MDG) starter overnight cultures (25 mM Na2HPO4, 25 mM KH2PO4, 50 mM NH4Cl, 5 mM Na2SO4, 2 mM MgSO4, 0.5% glucose, 0.25% aspartate, 50 μM trace metals) and grown at 37 °C for ~16 h. These started cultures were used to inoculate 1 l M9ZB expression cultures (47.8 mM of Na2HPO4, 22 mM of KH2PO4, 18.7 mM of NH4Cl, 85.6 mM of NaCl, 1% Cas-amino acids, 0.5% glycerol, 2 mM of MgSO4, 2–50 μM of trace metals, 100 μg ml−1 of ampicillin, 34 μg ml−1 of chloramphenicol and Antifoam 204 (1:1000)) at an initial optical density of 0.05. The expression cultures were grown at 37 °C until reaching an optical density of 1.5–2.0 (~6 h). Isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (0.5 mM) was then added, and the culture was incubated at 16 °C for 16–20 h. Cultures were collected by centrifugation at 5,000g for 10 min. Cell pellets were either frozen or processed directly for purification. First, cells were resuspended in 60 ml lysis buffer per litre of culture (20 mM of HEPES at pH 7.5, 400 mM of NaCl, 10% glycerol, 20 mM of imidazole and 1 mM of dthiothreitol). Cultures were lysed by sonication. Debris from lysed cells was removed by centrifugation and the soluble material was bound to Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen). The resin was washed with lysis buffer, lysis buffer supplemented with 1 M salt, and then lysis buffer again. Elution was performed with lysis buffer supplemented with 300 mM of imidazole. Samples were then dialysed overnight in dialysis buffer (20 mM of HEPES-KOH at pH 7.5, 300 mM of KCl and 1 mM dthiothreitol), in 14-kDa-MWCO dialysis tubing (Ward’s Science) with SUMO2 cleavage by hSENP2 at 4 °C when purifying SUMO2-tagged proteins (pMS692). No protease was added when purifying smt3p-tagged proteins (pMS1006 or pMS1008). After dialysis, the samples were concentrated using a 30-kDa-MWCO centrifugal filter (Millipore Sigma) and purified by size-exclusion chromatography using a 16/600 Superdex 200 column (Cytiva) equilibrated with gel filtration buffer (20 mM of HEPES at pH 7.5, 250 mM of KCl and 1 mM of TCEP-KOH). Fractions containing the protein were pooled, concentrated, frozen with liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

For crystallization of both HepS and the trigger peptide–HepSH105A co-complex, purified proteins or complexes were diluted to 10 mg ml–1, and crystals were grown in hanging drop format using EasyXtal 15-well trays (NeXtal). For crystallization of apo-HepS, HepS with an N-terminal His-SUMO2 tag was expressed from pMS692, and the SUMO tag was cleaved during purification. Crystals formed over one week with the reservoir solution (0.2 M of CaCl2, 0.1 M of Tris at pH 8.5, and 15% (w/v) PEG 4000). Harvested crystals were cryo-protected in a solution of 0.2 M of CaCl2, 0.1 M of Tris at pH 8.5, 16% (w/v) PEG 4000 and 20% ethylene glycol, before plunging in liquid nitrogen. For crystallization of the HepS + CSF fragment complex, HepSH105A with a C-terminal 1x-Flag tag was expressed from pMS832 and the trigger peptide (residues 902-932) with an N-terminal His-smt3p tag was expressed from pMS1006. Crystals of the complex formed over one week in the reservoir solution consisting of 0.2 M of sodium acetate, 16% PEG 4000 and 0.1 M of Tris pH 8.5. Harvested crystals were cryo-protected in a solution of 10% glycerol, 0.2 M of sodium acetate, 16% PEG 400, and 0.1 M of Tris pH at 8.5 before plunging in liquid nitrogen. X-ray diffraction data were collected at the National Synchrotron Light Source II (NSLS2) beamline (beamlines AMX 17-ID-154 (apo-HepS) and FMX55 17-ID-2 (HepS–J complex). Data were processed with autoPROC and Aimless56,57,58 Experimental phase information was determined by molecular replacement using Phaser-MR in PHENIX59. For apo-HepS AlphaFold2 models of monomeric HepS were used for molecular replacement. For the complex, the apo structure of HepS trimmed of all loops was used for molecular replacement. For both structures, model building was completed in Coot and then refined in PHENIX. The final structures were refined with stereochemistry statistics as reported in Extended Data Table 1. All structure images and figures were prepared in PyMOL60. Measurements of Cα distances and shift in apo versus active forms were also performed in PyMOL. H105 was modelled using SWISS-MODEL61,62.

Bioinformatics of HepS

The structures of HepS were predicted using AlphaFold collab15. The rank 1 model was used for homology searching of known structures through the DALI server15. DALI output is reported in Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1. Gene neighbourhood analysis was performed with WebFlaGs18 with the amino acid sequence of STM14_3211 being used to search the entire refseq database and extend the search region to additional neighbouring genes (search against refseq_full, max. 100 hits, Blastp E-value 1 × 10–3, Jackhammer E-value 1 × 10–6, Jackhammer iterations 3, Flanking genes 6).

HepS homologues were identified using Salmonella enterica HepS as a query in position-specific iterative BLAST (PSI-BLAST) searches against the NCBI non-redundant protein database. Five rounds of PSI-BLAST were performed with an E-value cutoff of 0.005, BLOSUM62 scoring matrix, gap existence cost of 11, gap extension cost of 1, and conditional compositional score matrix adjustment. Hits from each round were aligned using MAFFT63 (automatic strategy selection). Candidate sequences were selected to refine the position-specific scoring matrix on the basis of the presence of the conserved HEPN domain RX4–6H signature motif and structural predictions from AlphaFold364 for representative homologues. To focus the analysis on standalone HepS homologues, sequences longer than 250 amino acids or containing additional predicted domains were excluded. A total of 393 non-redundant sequences were selected.

Selected sequences were aligned using Clustal Omega65 with protein-specific mode and automatic strategy optimization. The resulting alignment was used to construct a maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree in Geneious Prime (v2025.2.1) using FastTree (v2.1.11)66 with a gamma-distributed model of rate heterogeneity and 20 discrete rate categories. iTOL67 was used for tree visualization and annotation. Taxonomic classifications and conserved domain annotations were derived from metadata associated with each NCBI non-redundant protein entry.

Gene neighbourhood analysis was performed using WebFLaGs18. A curated list of NCBI protein accession numbers corresponding to selected hepS homologues was submitted directly to the WebFLaGs server. For each input protein, WebFLaGs retrieved the four upstream and four downstream genes from the corresponding RefSeq genome and clustered neighbouring genes based on sequence similarity using Jackhmmer (E-value cutoff 1 × 10–6, three iterations). Functional descriptions, protein sequences, and conserved domain information were retrieved for each neighbouring gene from the NCBI database. Genes predicted to encode phage structural components (for example, tail, baseplate, capsid) or integrases were manually annotated as indicative of prophage association.

HepS modelling with tRNA or JF924S fragment

Model of HepS-Thr-tRNA(GGT) was generated using the HDock34 rigid-body docking software where structure of active HepS-J complex and Thr-tRNA(GGT) model were used as receptors and ligands, respectively. The modelling of HepS with trigger peptide JF924S was performed using AlphaFold 364 with amino acid sequences of HepS protein and JF924S trigger peptide provided. A model of HepS with JF924 trigger peptide was also prepared during analysis to account for the AlphaFold 3 modelling bias.

Identification and curation of J protein homologues

J protein homologues were identified using PSI-BLAST with the wild-type Escherichia phage lambda J protein as the query sequence. Searches were performed against the NCBI non-redundant protein database with an E-value threshold of 0.005. To focus the search on relevant phage sequences, results were restricted to entries annotated as members of the Siphoviridae family. A total of four PSI-BLAST iterations were conducted to expand homologue coverage while refining the position-specific scoring matrix PSSM. To improve the specificity of the final dataset, only sequences with ≥80% query coverage were retained. Sequences longer than 1,400 amino acids or annotated as partial were excluded to remove potentially fused or incomplete proteins. Furthermore, proteins from unclassified environmental samples were removed to avoid taxonomically ambiguous entries. After manual curation, a total of 290 high-confidence J protein homologues were retained for further analysis.

Multiple sequence alignment was performed using Clustal Omega v.1.2.3 (ref. 65) within Geneious Prime (v.2025.2.1), with protein-specific mode and automatic strategy optimization. Sequence logos and hydrophobicity profiles were generated in Geneious Prime. Residue hydrophobicity was calculated based on the aligned sequences using the software’s default settings.

Mass photometry

Refeyn mass photometry was used at the Center for Macromolecular Interactions at Harvard Medical School (RRID: SCR_018270). The oligomeric state of HepS, trigger peptide–HepSH105A co-complex and HepS oligomerization mutants were determined by mass photometry (TwoMP, Refeyn). Purified proteins were diluted to 200–400 nM in gel filtration buffer before analysis. Isopropanol and MilliQ-H2O cleaned coverslips were loaded with gaskets and placed on the objective lens with a drop of Immersol immersion oil (Zeiss). AcquireMP software (Refeyn) was used to find focus on gel filtration buffer only, then β-amylase and thyroglobin control or samples were diluted in the buffer 1:10 followed by immediate recording for 60 s. Ratiometric contrast measurements were converted to molecular weight measurements using DiscoverMP software (Refeyn). Automatic gaussian curve fitting was performed on all oligomeric states.

Western blotting of HepS and trigger peptide in complex

After co-immunoprecipitation, samples of purified complexes of HepS(H105A)–Flag and His-smt3p-trigger were run on 15% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) PAGE gels. Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes through the semi-dry transfer method on a BioRad Turboblotter. The transfer buffer was 20% ethanol, 0.5% w/v Tris-base, 0.5% SDS and 0.29% w/v glycine. Membranes were blocked for 1 h with 5% milk powder in PBS with 0.1% Tween-20 (PBS-T). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antibodies (HRP-Anti-6X His tag antibody 1:1000 (Abcam, ab1187) or HRP-Anti-FLAG-M2 1:5000 (Sigma, A8592)) were bound overnight (16–24 h) at 4 °C in 5% milk powder with PBS-T. Membranes were then washed three times with 10 ml PBS-T with each wash lasting at least 5 min. The HRP signal was detected with Clarity Western ECL Substrate (BioRad) according to manufacturer instructions. Blots were imaged with a BioRad Chemidoc on the chemiluminescent setting.

Using qPCR for prophage DNA

Samples were collected from either total bacterial culture or cell-free supernatants from MMC-treated cultures. A portion of the sample from each culture was treated with DNase I (ThermoFisher EN0521) for 30 min at 37 °C, followed by heat inactivation of DNase I at 75 °C for 10 min. Both samples were then boiled for 10 min at 95 °C and diluted by 1:8; 2 μl of the samples were then used in each quantitative PCR (qPCR) reaction. We performed qPCR using Luna Universal qPCR Master Mix (New England Biolabs M3003) with 10 μl reaction volumes in technical duplicates. We ran qPCRs on a QuantStudio 6 Pro Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems); the data were extracted from the QuantStudio web application (ThermoFisher) and further analysed using the ∆Ct method in which Ct refers to cycle threshold. Each prophage was assessed with two markers and the average was used to compare conditions.

Using RT–qPCR to quantify full-length tRNA

Full-length tRNA was quantified by reverse transcription qPCR (RT–qPCR), using primer sets with products that span the anticodon loop. Samples were collected from cell-free transcription or translation reactions with HepS alone, or HepS + the J protein (to induce cleavage). The reactions were diluted to 1:100 and 2 μl was used as the template for each qPCR reaction. RT–qPCR was performed using Luna Universal RT-qPCR Master Mix (New England Biolabs E3005) with 10 μl reaction volumes in technical triplicates. qPCRs were run on a QuantStudio 6 Pro Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) and qPCR data was extracted from the QuantStudio web application (ThermoFisher) and analysed with the ∆Ct method comparing samples with and without J.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism v.9.1.3 (Graph-Pad Software). Significant differences were determined with a Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA and corrected for multiple comparisons using Tukey’s test. The significance level (α) was set to 0.05 in all cases. Exact P values are indicated on each figure.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.