The BII represents the average remaining proportion of the abundance of indigenous faunal and floral populations in an area relative to an intact reference state. In this case, it means pre-colonial and pre-industrial conditions4. Calculation of the BII requires three sets of information: (1) a map of human impacts across the area (typically proxied by land use, which captures major land covers, uses and associated activities); (2) the richness of indigenous species that occur in the area; and (3) intactness scores—estimates of the remaining proportion of intact reference populations of these indigenous species under different conditions of human impact—on a scale from 0 (no remaining individuals) to 1 (same abundance as the reference) and, in rare cases, to 2 (two or more times the reference population)4,5. For species that thrive in human-modified landscapes, scores can be greater than 1 but not exceed 2 to avoid extremely large scores biasing aggregation exercises4,5. The intact reference is the population abundance that would have occurred in the area before alteration by modern industrial society (around 1700 ce)4. In most parts of sub-Saharan Africa, this corresponds to populations before the substantial alteration of the landscape triggered by colonial settlement, although we recognize that some declines would already have occurred by this point in time. Because information on species populations from this era is almost non-existent, standard protocol is to reference a remote protected or wilderness area with a natural disturbance regime (a hybrid–historical approach51) where necessary4.

The BII for a unit of land (pixel) is calculated by averaging, across the richness R of indigenous species that should occur in that pixel, the intactness score Isk of species s given the human impacts (that is, land use) in that pixel k, such that each species counts equally. That is,

$$\mathrmBII_\mathrmpixel=(1/R)\Sigma _sI_sk$$

(1)

The index can accommodate data scarcity. In the absence of intactness scores per species per land use, the BII can use intactness scores that represent groups of species that are expected to respond similarly to human impacts (functional response groups) and species richness information for the broader area (for example, ecoregion)4. In such cases, the BII for a pixel is determined as follows:

$$\mathrmBII_\mathrmpixel=(1/\Sigma _iR_i)\Sigma _iR_iI_ik$$

(2)

where Iik is the intactness score for functional response group i given the land use in that pixel k, weighted by the richness Ri of functional response group i (number of species or proportion of total species) in the relevant area (commonly, the ecoregion).

BII can be averaged across n pixels in an area of interest (for example, continent, biome, ecoregion or country) to provide a single BII score that accounts for the composition of both species and land uses:

$$\mathrmBII=(1/n)\Sigma \mathrmBII_\mathrmpixel$$

(3)

BII scores can be calculated for all species or a subset (for example, vertebrates, amphibians, among others). Here we made use of equations (2) and (3) to accommodate data scarcity. BII estimates were converted to percentages by multiplying by 100.

Intactness scores co-produced by experts

Determining intactness scores for indigenous species in sub-Saharan Africa based on field-collected data of population abundances across different land uses (including in comparable intact reference areas) is limited by a lack of appropriate data for most species20,52. Instead, we made use of a published dataset of intactness scores that were estimated as part of our Biodiversity Intactness Index for Africa project (https://bii4africa.org/) by way of a structured expert elicitation process that involved 200 experts in African flora and fauna5. The bii4africa dataset contains intactness scores (Iik in equation (2)) for species groups representing terrestrial vertebrates (tetrapods: ±5,400 amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals) and vascular plants (±45,000 forbs, trees and shrubs and graminoids), including all mainland Afrotropical ecoregions53 across 9 specific land uses of varied intensity (Supplementary Table 2). A detailed description of our elicitation process and resulting bii4africa dataset can be found in our previously published paper5, which recognizes the contributing experts as co-authors. Here we provide a summary (Extended Data Fig. 1).

A broad definition of expertise was used to identify experts, which was centred on experience of how sub-Saharan species are affected by human land uses. Diverse types of people can have such experience (for example, researchers, field guides, park rangers, conservation practitioners and museum curators). An expert was identified to lead an elicitation for each broad taxonomic group. Lead experts then recruited additional experts that met our definition of expertise, focusing on diversity geographically, taxonomically and professionally to promote elicitation rigour and to mitigate biases29,54,55,56. Additional experts were identified by snowballing among experts where needed to achieve a target group size of about 20 and followed best-practice guidelines29. We particularly sought African experts to overcome persistent biases towards Global North experts in ecological literature57,58. Biases towards well-published experts, taxa and geographies were challenging to completely overcome. Of the 200 experts who participated, there were more with experience in Southern (55% of experts) and East (33%) than Central (27%) and West (26%) Africa, with expert numbers also varying among taxonomic groups (12–38). Just over half the participating experts had university affiliations. Most resided in the region (72%) and 59% were from the region. All experts had place-based knowledge from the region, which informed the creation of a quantitative dataset through an iterative and interactive expert elicitation process. The process was informed by a published, modified-Delphi ‘IDEA’ protocol29 (multiple rounds of individual, independent expert estimation interspersed with group discussion and review), which draws on advances in expert elicitation that have been shown to improve data consistency.

For each broad taxonomic group, participating experts were convened in an online meeting to introduce the aim of the project, the notion of BII and how it is calculated and to explain the task of estimating intactness scores. Experts were given the opportunity to ask questions and voice concerns. It was not practical to ask experts to provide intactness scores for every species exposed to every combination of human activities across sub-Saharan Africa. Rather, we made use of a functional grouping approach4, asking experts to estimate the intactness of different groups of species (i in equation (2); ‘Sp_Groups’ tab in the bii4africa dataset5) in nine land uses characteristic of the region (k in equation (2); Supplementary Table 2). This contextualized generalization22 assumes that a functional group of species responds in the same way to the same type of land use across its regional range4. The exceptions were the 102 species of large mammals, for which experts decided to provide estimates at species level (with i representing a species in these instances). The intactness scores of plant groups were estimated by experts in each of the eight major biomes in the region (forest, Caesalpinioid-miombo humid savanna, mixed-Acacia savanna, grassland, shrubland, thicket, desert and fynbos)59,60,61. Both the species functional response groups and biomes were proposed by lead experts and refined on the basis of feedback from participating experts during the introductory meetings. Experts were instructed to make their intactness estimates at a landscape scale (that is, one or several square kilometres), considering the integrated impact of all characteristics of that landscape on each group of species.

Participating experts were given 2 weeks after the introductory meeting to independently provide their best-guess intactness scores through a survey spreadsheet. Experts estimated on average 155 intactness scores. The survey prompted experts to provide comments relevant to each estimate (for example, assumptions or uncertainties) to mitigate the risk of overconfidence and to detect potential inconsistencies between experts (for example, caused by linguistic uncertainties related to the survey62). A discussion meeting was convened in which the aggregated (anonymized) results per functional group and land use were presented to participating experts, based on evidence that group discussion can improve elicitation rigour29,54,55. Project and expert leads reflected on key trends and sources of variability. Experts were encouraged to share their experiences when undertaking the survey and to reflect on the aggregated results. We emphasized that the purpose of the discussion was not to reach consensus but rather to reduce uncertainties and biases by interrogating sources of variability, improving the consistency with which experts interpreted the survey instructions and cross-examining reasoning, assumptions and evidence to promote learning29,54,55. Experts were given 1 week to independently revise any of their scores based on insights gained in the discussion. Several experts withdrew during the process, stating time limitations or insufficient expertise, with 200 participating to completion. Their final scores are presented in the published bii4africa dataset5.

An average of 10 (s.d. = 7) experts provided an intactness estimate for each combination of functional response group (or species for large mammals) and land use (and biome for plants)5. Here we used mean intactness scores (that is, the average estimate across independent experts for each combination) as the most common form of data aggregation in structured expert elicitation protocols to counter the biases of individual experts29,54. The variability in scores among our sample of experts (expressed as 95% confidence intervals) was used to reflect the degree of uncertainty around BII estimates, which arose, for example, from differences in the place-based knowledge of the experts, unknowns or disagreements around how some functional response groups are affected by land uses and variability in the number of experts contributing to each aggregated estimate.

Species richness across ecoregions

For vertebrates, each species in the IUCN Red List with a sub-Saharan African range was allocated to a species functional response group in the bii4africa dataset5 by lead experts, with input from the participating experts where needed. This list was coupled with a list of species per ecoregion to determine the number of species (R in equation (2)) in each functional response group i in each ecoregion. Species lists per ecoregion were obtained by intersecting the Ecoregions2017 Resolve map53 with species range maps available through the IUCN Red List63 and Birdlife International64, including historical ranges and extinct species, as the BII is relative to pre-colonial and pre-industrial conditions.

Given the large number of vascular plant species, the bii4africa dataset5 instead lists the proportion of plant species per biome that occur in each functional response group in the broad groups of forbs, trees and shrubs, and graminoids. Proportional richness across the three broad plant groups in each biome was estimated based on the RAINBIO65,66 dataset of tropical African vascular plant species distributions. Species in RAINBIO were allocated into the three broad bii4africa plant groups as follows: graminoids, all species in the families Poaceae, Cyperaceae, Juncaceae and Restionaceae; trees and shrubs, all remaining species with the growth form tree, shrub, liana or epiphyte; and forbs, all remaining species with the growth form herb, shrublet or vine. The geolocations of each RAINBIO species entry were overlaid onto the Ecoregions2017 Resolve map53 to determine the proportion of species in each broad plant group in each ecoregion and associated biome. The proportion of total plant species in each functional response group in each biome could then be determined and multiplied by total vascular plant species richness estimates per ecoregion67 to estimate plant species richness Ri per functional response group i in each ecoregion.

Mapping land uses and intensities

The bii4africa dataset5 contains intactness scores for nine specific land uses to capture the major land cover types, uses and associated activities relevant to sub-Saharan Africa (Supplementary Table 2). These include the following types: (1a) mixed settlements; (1b) dense urban; (2) timber plantations; (3a/4a) non-intensive smallholder croplands; (3b) tree croplands; (4b) intensive large-scale croplands; (5) strictly protected areas; (6a) near-natural lands; and (6b) intensive rangelands. These land uses cover six broad classes, and high-intensity and low-intensity options for those classes that can vary notably in their intensity in the region (Extended Data Fig. 8). To map BII, we needed a land-use map that reflected these six broad land use classes and the spectrum of intensities that occur in four of these classes (Fig. 3a).

We used an established decision-tree algorithm68,69 built on (area) standardized thresholds of human population density and/or land cover to allocate each pixel in sub-Saharan Africa into one of six broad land-use classes to reflect the differences between the land uses described by experts (Extended Data Fig. 8). Settlement pixels (1) were allocated first, followed by timber plantations (2), tree croplands (3) and croplands (4), and thereafter protected pixels (5)68,69. All remaining pixels were then allocated to the unprotected untransformed class (6).

In four out of the six broad land-use classes, we then scored each pixel based on its intensity, using a protocol comparable with other well-established human intensity indices70. Proxies of intensity relevant to each class were selected to reflect the land-use descriptions for which experts estimated intactness scores (Extended Data Fig. 8). Each variable was standardized using minmax scaling, such that the pixel in a land use class with the lowest and highest value scored 0 and 1, respectively. An average of the relevant standardized variables in a land-use class was computed and then rescaled using minmax scaling. This value represented the relative intensity of each pixel in a land-use class (that is, the pixel scoring 0 versus 1 had the respective lowest versus highest mean intensity score in that class). When scaling variables that did not have a natural upper bound and were therefore susceptible to high outlier scores (for example, population density, livestock density or nitrogen input; Extended Data Table 2), the 90th percentile value was used as the maximum in the minmax scaling.

Before scaling livestock (cattle, goat or sheep) density as a proxy for intensity (Extended Data Fig. 8), we accounted for the fact that some areas can support higher grazing pressure. A unimodal relationship has been shown between potential African mammal herbivore biomass and mean annual rainfall (MAR), peaking at about 1,700 kg km–2 and around 700 mm MAR71. Moreover, potential African mammal herbivore biomass is higher in areas with higher nutrient soils72. Hence, we grouped pixels into comparable sets based on their MAR (in 400 mm bins) and soil nutrients (high, medium or low). We then minmax-scaled livestock density in each of these sets to ensure intensity was quantified across comparable areas.

One of the nine land use classes for which experts estimated intactness scores was a well-managed, strictly protected area (Supplementary Table 2). We limited our allocation of this land use to pixels occurring in protected areas with IUCN management categories I–III, as these have strict restrictions on human activities73. Four countries in sub-Saharan Africa do not make use of IUCN management categories, with strictly protected areas identified case by case (Supplementary Methods 1). Protected pixels were assigned after settlements and cultivated lands (Extended Data Fig. 8), which meant that any transformed lands in protected areas (that is, ineffective protected areas) were not allocated to the protected land use. We were unable to exclude strictly protected lands that are untransformed but subject to unsustainable resource harvesting—a limitation that means we may overestimate BII in some protected areas. By contrast, BII may be underestimated in lands that are strictly protected in practice but not on paper. The protected area allocation and therefore BII map can be updated should management effectiveness data become available for all protected areas.

We mapped land uses in Google Earth Engine at a resolution of 1 × 1 km and 8 × 8 km to reflect the landscape scale at which experts estimated intactness scores. The finer resolution may be useful to some applications but is computationally demanding to work with (>20 million pixels). The coarser resolution is likely to be more appropriate for certain species groups, such as large mammals and wide-ranging birds, which are unlikely to survive in 1-km2 patches of habitat. All land-use variables were obtained from pre-existing map products that spanned the full region to ensure consistency of inputs (Extended Data Table 2). When a map pixel covered more than one unit of a variable layer, overlapping variable values were either summed (in the case of land cover) or averaged, weighted relative to their degree of overlap (remaining variables). Missing values were imputed using the nearest provided value.

Calculating and mapping BII

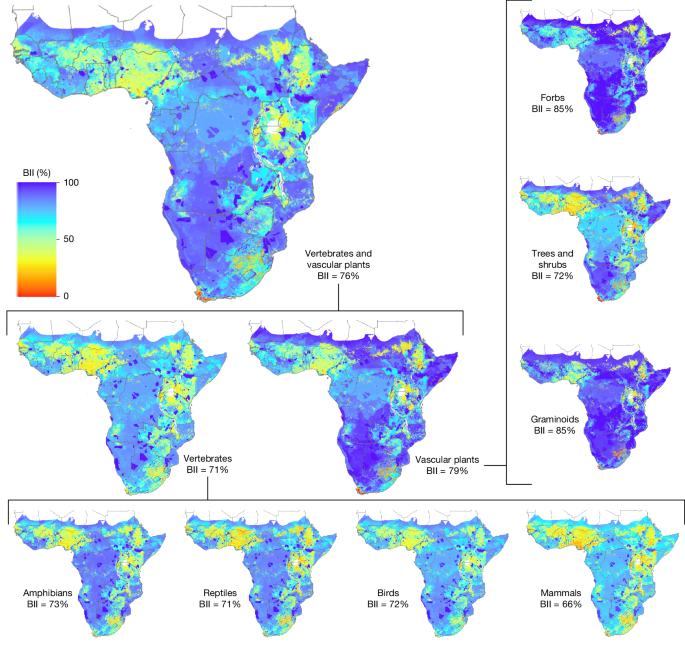

BII scores for each pixel in the land-use map were estimated using equation (2) based on the average (across experts) intactness scores Iik for functional response groups i in land use class k (adjusted for intensity in four of the classes (see next paragraph)) and the ecoregion (which influences species richness R per functional response group i). Fifteen ecoregions were classified as mosaics categorized by two biomes (for example, the Angolan montane forest–grassland mosaic ecoregion is a mosaic of the forest and grassland biomes)5, with plant intactness scores for the two biomes averaged for these ecoregions. A BII score was determined for the following categories: (1) terrestrial vertebrates and plants; (2) vertebrates; (3) plants; (4) each of the four vertebrate classes (amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals) and three broad plant groups (forbs, trees and shrubs, graminoids); and (5) each of 146 functional response groups (with the large mammal species being categorized into the 12 functional response groups proposed in the bii4africa dataset5). To reflect uncertainty, we similarly estimated ‘lower limit’ and ‘upper limit’ BII scores for each pixel based on the lower and upper limits of the 95% confidence intervals around average intactness scores Iik. Lower-limit-BII and upper-limit-BII scores were determined for the following categories: (1) terrestrial vertebrates and plants; (2) vertebrates; and (3) plants.

To calculate BII (and lower-limit-BII and upper-limit-BII) scores in pixels with a land-use intensity continuum (Extended Data Fig. 8), the maximum (low intensity) and minimum (high intensity) intactness scores Iik were averaged and weighted according to the intensity of that pixel. For example, for settlement land-use pixels, those with an intensity of zero were allocated the ‘1a. Mixed settlements’ intactness scores, whereas those with an intensity of one were allocated the ‘1b. Dense urban’ scores (Supplementary Table 2). A pixel with an intensity of 0.5 received an average of the minimum and maximum scores. BII maps were produced in R.

Analyses and validation

We calculated the BII for sub-Saharan Africa by averaging BII scores across all pixels in the 1 × 1 km and 8 × 8 km maps. Given the high degree of correspondence (75.53% and 75.54%, respectively), further analyses were performed using the 8 × 8 km maps. We quantified the BII per country, ecoregion, biome and land use by averaging scores across all relevant pixels. We quantified the uncertainty around these BII values by averaging upper-limit-BII scores and lower-limit-BII scores across all relevant pixels. The percentage of pixels in each broad land-use class and the average BII of those pixels were used to determine the proportional contribution of each land use to the total BII that had been lost and that remained. We similarly assessed the contribution of ‘medium–high intensity’ versus ‘low intensity’ land uses to lost and remaining BII in each biome (pixels with intensity scores ≥0.25 and <0.25, respectively).

We followed a previously described method15 to assess the robustness of the BII map by comparing it to the human footprint index74 (HFI)—a composite map of anthropogenic pressure on natural ecosystems—and the biomass modification index75 (BMI)—a mapped synthesis of estimates of current vegetation biomass relative to that in the same location without human disturbance. We also related BII to the biodiversity habitat index76 (BHI)—the effective proportion of habitat remaining in a pixel, adjusting for the effects of the condition and functional connectivity of habitat. We would not expect these indicators to perfectly correlate with BII, as the BII accounts for varied responses of different species populations to human pressures and accounts for important regional contextual factors that may be overlooked in the other global indicators, such as smallholder versus large-scale croplands and rangelands versus planted pastures. However, we would expect areas with a higher BII to generally have a lower HFI, lower BMI and higher BHI, and vice versa15. To assess these relationships, we calculated the Spearman’s rank correlation of the average BII score and the average HFI, BMI and BHI scores across ecoregions. Using the previously described method15, we categorized each ecoregion as a biodiversity hotspot if the area of the ecoregion overlapped by ≥50% with a biodiversity hotspot (a priority area of exceptional endemism that has lost ≥70% of its primary vegetation)32,77. Hotspot ecoregions should typically have lower BII scores than other ecoregions, and we tested this by comparing the average BII scores of hotspots and other ecoregions using a two-sided Mann–Whitney U-test.

As an additional validity check, species-level BII estimates were compared to the risk of extinction of each species (according to the IUCN Red List63), with the expectation that a valid BII assessment should generally predict lower BII for more threatened species. We quantified the average BII of each vertebrate species (according to its functional response group or at species-level for large mammals) across its regional range. We then ran a generalized linear mixed-effects model (equation (4)), with a Gaussian distribution given data normality, to assess whether the IUCN threat category (‘IUCN category’) of a species (that is, critically endangered, endangered, vulnerable, near threatened or least concern) was a significant predictor of its average BII across its range (‘intactness index’). We included 4,887 sub-Saharan African vertebrate species with a threat category (we excluded 479 data-deficient species and 3 extinct species). We included IUCN threat category as a fixed effect and the range size of the species (‘range size scaled’) to isolate the effect of IUCN threat category on intactness, independently of the influence of range size (with range size being a consideration in the IUCN Red Listing process). The model also accounted for variation in intactness across taxonomic classes (‘Class’) and their nested functional response groups (‘RG’). These nested random effects capture baseline differences in intactness due to taxonomic and functional groupings, which ensures that the fixed effects are not biased by class-level or RG-specific variability.

$$\beginarrayl\mathrmIntactness\,\mathrmindex \sim \mathrmIUCN\,\mathrmcategory+\mathrmrange\,\mathrmsize\,\mathrmscaled\\ \,\,\,\,+\,(1|\mathrmClass/\mathrmRG)\endarray$$

(4)

This model was run using the lme4 package in R. We checked that the response variable and model residuals were normally distributed and that the two fixed effects were not competing for variance in the global model (variance inflation factor close to 1). Range size was scaled and centred to avoid overdispersion and leverage. We ran an analysis of variance to test whether the fixed effects were significant predictors of intactness and post hoc Tukey tests to check for significance between IUCN categories (corrected for multiple pairwise comparisons).

Finally, we compared the results of our BII assessment with those of two previous assessments. First, the original BII assessment that was published for southern Africa in 2005 based on a simplified expert elicitation4 and second, a globally modelled assessment that was published in 2016 (ref. 13).

Caveats

People are susceptible to a range of cognitive biases that can erode the quality of expert-elicited data (for example, based on information availability, overconfidence, linguistic uncertainty or groupthink)56,62,78,79. It can also be challenging to identify who is an expert54. We sought to mitigate such challenges by selecting a diverse group of experts, based on experience rather than status29,54,55,80, and taking them through a structured, iterative elicitation using an evidence-based protocol for improving rigour29. Our data-aggregation approach reduces the effect of expert biases29, assuming such biases are independent rather than systematic (for example, no groupthink81,82). However, expertise was overrepresented for certain geographies (for example, southern Africa), nationalities (for example, South Africa), taxonomic groups (for example, large mammals) and professions (for example, researchers)5, which may have resulted in unknown systematic biases in aggregated expert scores. Limitations to diverse expert participation probably include digital inequities, lack of incentive for non-researchers to participate in research and language barriers (particularly in Francophone countries). Furthermore, although overconfidence can be mitigated by asking experts to provide an upper and lower plausible estimate together with a best guess29, we found this to be cumbersome and confusing in a pilot with lead experts, given the high number of estimates. Instead, we mitigated against overconfidence by nudging experts to consider uncertainties and assumptions underlying their estimates, and encouraging critical evaluation during the discussion meeting29,54,55. Given the uncertainties inherent in expert elicitation, applications of this BII assessment should take note of the confidence intervals around mean estimates, which reflect known uncertainty among experts, while keeping in mind potential unknown uncertainties such as possible systematic bias in our expert group that are not reflected in these confidence intervals and that may have had a directional effect on our results.

Our approach of contextualized generalization—integrating place-based knowledge into a broad-scale regional product that speaks to national and international decision-making needs—required several epistemological and methodological compromises. Epistemologically, the use of a pre-defined, relative (to a reference state) and bounded notion of biodiversity intactness is influenced by Western ways of thinking about science and ecology24 and reflects decisions made by the analysts as opposed to the experts83. We countered Western dominance by bringing more African expertise into ecology and adding insight around important aspects of regional context that are often ignored while using concepts and metrics that are embedded in international agreements such as the GBF, which countries are required to report to.

Methodologically, to limit the number of estimates that each expert was asked to provide, we assessed BII at the level of functional response groups and land-use categories. We therefore compromised on potentially important variability among species in a functional group or land-use configurations in a category, which may influence BII. Furthermore, our analyses relied on published land-use and species-distribution datasets that may contain classification or coverage limitations. Notably, some land-use activities (for example, harvesting) are harder to map than those that can be seen from space (for example, crop cover), which limited our ability to account for these activities to mapped proxies such as population density and human infrastructure14,74. This limitation means we probably overestimate BII where human activities such as harvesting are notably more intensive in a given land use than predicted on average by our experts or mapped intensity proxies, and the converse in places that have notably lower-than-expected exploitation of wildlife due to, for example, taboos against bushmeat. Furthermore, the intensity of rangeland use is particularly challenging to map, and we advanced standard approaches by controlling for soil and rainfall in our translation of livestock density into a measure of land-use intensity in attempt to better account for local context. The accuracy of BII mapping based on our published expert estimates5 can probably be substantially improved over time with advances in land-use mapping.

Despite these limitations to our approach, the resulting BII corroborated other assessments of human pressure. However, we note that these other assessments cannot be considered entirely independent given that they all rely on land-cover data and its associated limitations. Trends in the BII estimates for individual vertebrate species across their particular ranges were also robust when compared with their IUCN threat status. This comparison demonstrates that despite uncertainties at each step, our approach of functionally grouping species, asking diverse experts to estimate how those groups would be affected by characteristic land uses and mapping those estimates based on land uses and species ranges across the region led to intactness predictions that correspond as expected with an independent (although also expert-informed) assessment of the threat categories of individual species.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.