Zebrafish lines and handling

Zebrafish (D. rerio) adults and embryos were maintained and handled according to established protocols51.

The experiments were approved and licensed by the local animal ethics committee (Landesdirektion Sachsen, Germany; licence no. DD24.1-5131/394/33) and executed in accordance with the European Communities Council Directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes, as well as the German Animal Welfare Act. Sample sizes were chosen to allow statistically significant experiments while minimizing the number of animals used. Adult (4 months to 2 years of age) female and male zebrafish were used to produce embryos, and the sex of the embryos was not considered. Randomization and blinding were not applicable in this study. Transgenic animals had mixed background from AB and TL strains. Zebrafish transgenic lines used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Zebrafish sample preparation

Embryos were collected in E3 medium (5 mM NaCl, 0.17 mM KCl, 0.33 mM CaCl2 and 0.33 mM MgSO4) within 5 min after spawning and kept at 24–28 °C. Embryo clutch quality was inspected on a dissection stereomicroscope. Beads, fluorescent proteins, ferrofluid droplets or chemicals (SbTubA4P) were injected into the cytoplasm of one-cell stage transgenic zebrafish embryos according to52. Injection volumes were calibrated to 0.5 nl. Depending on the experiment, 0.5–1 nl were injected per embryo.

Embryos were mechanically dechorionated using forceps and mounted in 1% low-melting-point agarose (Sigma) in E3 medium supplemented with 25% w/v iodixanol (OptiPrep, STEMCELL Technologies 07820) for refractive index matching53 on a CELLVIEW cell culture glass bottom dish (Greiner Bio-One 627860). Embryos were brought closer to the coverslip surface by keeping the dish upside down until agarose solidified, since the embryos float in the mounting media containing OptiPrep54.

For magnetic tweezer, optical tweezer and band length experiments, dechorionated embryos were mounted in 0.5% low-melting-point agarose (Sigma) in E3 medium (without OptiPrep). Embryos were manually oriented before agarose solidification using a flamed glass capillary.

For measuring ingression velocity, embryos were mounted in 1% low-melting-point agarose (Sigma) in E3 medium (without OptiPrep) within their chorion. Embryos were manually oriented before agarose solidification using a flamed glass capillary.

Chemical treatments

Dechorionated embryos at the one-cell stage were mounted in 0.5–1% low-melting-point agarose (Sigma-Aldrich), 25% OptiPrep Density Gradient Medium (OptiPrep, STEMCELL Technologies 07820) supplemented with 10 µg ml−1 cytochalasin B from Drechslera dematioidea (Sigma-Aldrich), 200 µg ml−1 cycloheximide (239763-1GM), 10 µg ml−1 nocodazole (Thermo Scientific Chemicals 10762633) or DMSO control in a CELLVIEW cell culture glass bottom dish (Greiner Bio-One 627860).

Light sheet microscopy

For the overview, data for Supplementary Fig. 1a were obtained using Zeiss Light Sheet Z.1, lateral illumination and detection geometry, equipped with 2 PCO edge 5.5 m, monochrome sCMOS cameras (SN 61000966, 61004862) for detection. Imaged with Zeiss Plan Apo 20× (1.0 NA) Water DIC objective. Controlled through Zeiss ZEN 2014 SP1 9.2.10.54 software.

Confocal microscopy

For all confocal data except laser ablation, magnetic tweezers, and optical tweezers, the following microscope was used: Spinning disk confocal Andor Revolution platform with Borealis extension, Andor IX 83 inverted stand, Yokogawa CSU-W1 scan head, equipped with an Olympus silicone oil-immersion objective (30×/1.08 U Plan SApo, Silicone, OLYMPUS), or air objective (Olympus UplanXApo 20×/0.80 Air), recording with simultaneous imaging of two fluorophores with two Andor iXon Ultra 888, Monochrome EMCCD cameras (dexel size 13 µm).

For laser ablation, magnetic tweezers, and optical tweezers data, the following microscope was used: Spinning disk confocal Nikon Ti Eclipse, Yokogawa CSU-X1, equipped with a back-illuminated EMCCD camera (iXon DU-888 or DU-897, Andor) and a 60× water-immersion objective (Nikon Plan Apo VC 60× WI, NA 1.2) for laser ablation and optical tweezers, as well as 20× objective (Nikon Plan Apo 20× air, NA 0.75) for magnetic tweezers. Image acquisition was controlled by Andor iQ software in laser ablation and magnetic tweezer experiments, and through Nikon NIS-Elements software for optical tweezer experiments, as well as laser ablation shown in Fig. 2a.

Epifluorescence microscopy

The data shown in Supplementary Fig. 5e were obtained with a Nikon Ti Eclipse microscope body using epifluorescence imaging through a 20× air, NA 0.5 objective, recorded with a Hamamatsu Flash 4.0 camera, controlled through µManager software55.

Laser ablation

For laser ablation, a mode-locked Ti:Sapphire laser (Coherent Chameleon Vision II) was coupled into the back port of the Nikon spinning disc microscope as previously described54. The custom-built laser ablation setup is based on a previously described layout56. Laser ablation was performed using a wavelength of 800 nm and typically a power of 1 mW after the pulse picker. Line cuts perpendicular to the contractile band were implemented by moving the sample with a high-precision piezo stage (PInano) relative to the stationary cutting laser. The cutting procedure was automatically executed by a custom-written software that controlled the piezo stage and a mechanical shutter in the optical path. The lengths of the cut were adjusted according to contractile band width (typically 20 µm cut length). To capture the fast dynamics of actin band recoil and recovery, single z-planes of the contractile band were acquired every 200–300 ms. The cut contractile band recovered at the ablation site within approximately 10 s and the subsequent cell divisions proceeded normally after ablation. For cuts within the band the length of the cut was 2 µm.

Magnetic tweezers experiments

Fluorescent ferromagnetic beads were prepared by coating 2.8 µm Dynabeads Protein A (Invitrogen 10002D, Thermo Fisher Scientific) with anti-myc antibody, non-specifically labelled with DyLight 550 (Thermo Fisher Scientific 84530). The antibody-coated beads were additionally coated with polyethylene glygol as described57. Approximately 1–20 beads were injected per embryo into the cytoplasm at 1-cell stage. The samples were imaged on Nikon spinning disc confocal microscope (see above) for unperturbed embryos and on Nikon Ti Eclipse epifluorescence microscope for nocodazole and taxol-treated embryos.

Magnetic tweezers were home-built by inserting a pointed ferromagnetic rod into a solenoid. The rod was 6 mm in diameter and 120 mm long, made of HyMu-80 (Carpenter Technology). One end was sharpened to a 45° angle, which was introduced to the sample in the experiments. A 350-thread solenoid was made from a 0.5 mm diameter copper, wrapped around a Teflon support. Electric current was introduced to the solenoid with a voltage-controlled current generator, custom-built in house. Voltage, introduced to the current generator, was controlled with a laptop and a microcontroller (Arduino mini) though a custom script. The tip was mounted on an InjectMan NI2 micromanipulator (Eppendorf) for an easy and precise positioning of the tip. The tweezers were mounted on a Nikon spinning disc confocal microscope or an epifluorescence microscope.

Forces produced by the magnetic tweezers were calibrated by displacing the 2.8 µm Dynabeads (same type of the beads as in the experiment) in glycerol at 20 C (viscosity of glycerol at 20 °C is η = 1.412 Pa s). We ensured that the beads were at least 10 µm away from the glass and each other to avoid hydrostatic interactions with the surface. The voltage was set to 1,000 mV and the corresponding current through the solenoid was about 1,000 mA. The beads were tracked with TrackMate plugin in Fiji and the tracks were analysed with Python. Force–distance curves were obtained from 22 beads for the spinning disk setup and 59 beads for the epifluorescence setup (Supplementary Fig. 6a) and were fitted with a double exponential function, \(f(x)={a}_{1}{{\rm{e}}}^{-{k}_{1}x}+{a}_{2}{{\rm{e}}}^{-{k}_{2}x}\), which was used to infer the force on the beads in zebrafish.

Optical tweezers setup

For optical tweezer measurements, Spherotech SPHERO Carboxyl Fluorescent Particles (CFP-2058-2), pink, 2.15 µm were coated with PLL-PEG as described58 for passivation. Beads were injected into 1-cell stage zebrafish embryos as described above; bead solution was diluted to result in 5–20 beads per embryo.

The optical tweezer (Impetux, SENSOCELL) was set up as previously described59,60. In brief, the SENSOCELL setup was coupled to a Nikon Ti Eclipse confocal microscope by replacing the condenser with a calibration-free optical force sensor operating through detection of changes in light momentum. The 1,064 nm trapping laser was focussed onto the imaging plane of a 60× water-immersion objective (Nikon Plan Apo VC 60× WI, NA 1.2) creating an optical trap. The trap was manipulated using the manufacturers LightACE software.

Active microrheology measurements with optical tweezers

The 1,064 nm trapping laser was used to trap a single bead and set to oscillate as described60. The oscillation frequencies used ranged from 0.5–6,250 Hz (data fitted up to 2,056 Hz), with a displacement amplitude of 1 µm and oscillation periods decreasing with increasing frequency (Supplementary Table 2). Measurements were made in interphase and M-phase (inferred by microtubule morphology) between 1-cell and 4-cell stage. The data were exported from the manufacturers RheoAnalysis software and further analysed using Wolfram Mathematica and Python (described ‘Image processing’).

Photoactivation experiments

SbTubA4P was provided by O. Thorn-Seshold30. Prior to photocontrol experiments, the dose for inhibition was established using fully activated compounds as described61. Embryos were collected at 1-cell stage and injected with 1 nl of 1 mM – 2 mM SBTubA4P solution in the dark, only exposed to red light. Embryos were then mounted in agarose as described above and imaged on a confocal spinning disc microscope. The inhibitor was activated with 405 wavelength light either by taking a z-stack with a 405-laser or AMH fluorescent lamp, or by illumination of specific area using 405 nm Mosaic DMD.

For photoactivation experiments during interphase, where band ingression velocity was monitored, SbTubA4P was added to the mounting media, by diluting 2–3 µl of 10 mM SbTubA4P stock in 1 ml 0.5% low-melting-point agarose (at 37 °C) to a final concentration of 20–30 µM. Embryos were handled in the dark and the photoactivation was performed as above. For photoactivation in interphase arrested embryos, 10–20 µg ml−1 cycloheximide were added to the mounting media in addition to SbTubA4P.

Ferrofluid droplet and obstacle experiments

Ferrofluid was provided by O. Campas. Ferrofluid was injected into the cell of a 1-cell stage transgenic zebrafish embryo as described36.

Magnet holder for magnetic field was 3D printed (material: PLA prusa Galaxy Black; printer: Prusa mini) based on a model obtained from O. Campas and was equipped with grade N52 magnets (K&J Magnetics) as described36. The magnet holder was attached to the lid off CELLVIEW cell culture glass bottom dish (Greiner Bio-One 627860), to ensure reproducible spacing. To apply the magnetic field during imaging the lid and magnet holder were placed on the dish. To analyse the extension of ferrofluid droplets, z-stacks were turned into maximum intensity projections and an ellipse was fitted using the Fiji particle analysis plugin. The major axis of the ellipse was then plotted. Ferrofluid was found to nucleate microtubules and therefore used for obstacle experiments, by injecting approximately 1 nl into the centre of the embryo cytoplasm, without magnetic deformation.

Image processing

All raw imaging data were processed in Fiji62. The raw tiff data were turned into maximum intensity projections.

Laser ablation analysis

For the laser ablation data in Fig. 1c, the microtubule channel was averaged across four time frames using the Fiji Walking Average tool. For the magnetic bead data shown in Supplementary Fig. 5e the bead channel was despeckled.

Recoil of the contractile band following laser ablation within the band was measured from kymographs. All the measured data were taken with 300 ms time interval and 0.12 μm pixel size. The data were divided into M-phase and interphase, based on microtubule morphology such as spindle presence, and in some cases DNA morphology such as nuclei or metaphase plate. Six embryos were measured in M-phase (11 measurements, recoiling ends plotted separately, therefore 22 points) and 9 embryos were measured in interphase (18 measurements, thus 36 recoiling ends). Lines with line width 7–9 pixels were drawn perpendicularly to the cut, and a kymograph was made from the line during the time from cut to end of recoil. The kymographs were cropped such that the time when the sample was still moving during the cut was removed, as this would influence the detected contours in later steps. The kymographs were processed in Python: the data were thresholded with the Otsu method and contours were detected using skimage.measure.find_contours63. The curves were fit with an exponential function \(y=A(1-{{\rm{e}}}^{-\frac{x}{{x}_{0}}})+c\), the initial recoil velocity A/x0 was extracted and converted to µm s−1. Only the first cut in any embryo was analysed. The P value was calculated using scipy.stats.ttest_ind (two-sided t-test) and the data were plotted in Python. In box plots, each whisker extends to the furthest data point in each wing that is within 1.5 times the interquartile range. Data points further than that distance are considered outliers and are marked with dots.

Recoil of the contractile band in comparison to the actin grey value of the band recovery were measured manually using the line tool in Fiji. A line was drawn within the cut between the two severed ends of the band. The line width was adjusted to be slightly below the width of the band. The line was adjusted at every time frame to match the length of the recoil, and the average grey value of the line was measured. For normalization, a line was drawn before the cut along the band as a normalization for the actin grey value. The recoil was normalized using the minimum and maximum value of the recoil length. Only the first cut in any embryo was analysed.

Contractile band retraction analysis

Contractile band retraction velocities following SbTubA4P or cycloheximide treatments were determined by processing the image with particle image velocimetry in Matlab (Matlab v.R2021a, PIVlab64,65 v.3.02). For this analysis, nine embryos were measured for SbTubA4P and cycloheximide, respectively. PIV settings were: PIV algorithm: FFT window deformation, Pass 1: interrogation area 128 pixels, step 64 pixels. Pass 2: interrogation area 64 pixels, step 32 pixels. Sub-pixel estimator: Gauss 2 × 3-point (standard), Correlation robustness: Standard. Image pre-processing for PIV was: in Fiji: create input: maximum intensity projection, save as tif image sequence. In Matlab PIVlab: Enable CLAHE, Window size 64 pixels; auto contrast stretch. The PIV output data were further processed using Python. Each PIV dataset was aligned with the band along the y axis. We took the average of the flow velocity within 25 µm of the y axis, giving an average velocity \(\bar{v}(\,y,t)\). From this, we determined the end points of the band as the points with the highest positive and negative speeds. This gave us a timeseries of the band end position over time and the flow speed at this point. From this, we calculated the average velocity of the band ends points, the average contractile flow speed at the end points, and the band growth speed as the difference between the two, both in M-phase and interphase. The P value was calculated using scipy.stats.ttest_ind (two-sided t-test); error bars indicate the s.d.

Contractile band end retraction velocity during M-phase was measured using manual tracking plugin in Fiji66 (v.2.1.1). The data for measuring was five embryos, imaged by mounting them on the side, so that the contractile band could be observed at its end (the one end that was facing the objective was measured per embryo). The embryos were imaged with a 20× air or 30× silicon oil objective on Andor spinning disk (see above), with 15–30 s time resolution. For analysis the data were averaged (Fiji Multi Kymograph Walking Average Plugin) over 2 timeframes for 30 s data and over 4 timeframes for 15 s data. The end of the band was plotted for five embryos together, normalized for the lowest value of each sample for alignment. The trajectories were fitted individually and the arithmetic mean of the slopes as well as the root mean square error were calculated to obtain the average retraction velocity.

Band length measurements

The total length of the contractile band was measured using the Simple Neurite Trace (SNT)67, v.4.2.1 plugin in Fiji. The cursor auto-snapping and auto-tracing were disabled, and the band length was measured by manually tracing the band in the 3-dimensional z-stack in every time frame across 45 min (time interval 30–60 s) in 5 embryos. In one of the embryos, the entire band was measured, in the other four embryos, the centre of the band was defined as the centre from where it started to grow, and half of the band was measured (as the full band exceeded the image). The measurements of half of the band were multiplied by two in order to compare them to the measurement of the full band.

Band ingression analysis

Ingression of the band was measured using manual tracking plugin in Fiji66 (v.2.1.1) in six embryos. The ingression was determined as difference between the lowest point of the ingression and the highest point of the cortex (imaged and tracked using actin (utrophin) or membrane (PH-Halo, kindly provided by P. Barahtjan, labelled with JF646)). To ensure that the ingression was not affected by mounting in agarose, the embryos were mounted within their chorion to avoid confinement. The cell cycle of the embryos was determined based on morphological criteria such as spindle or microtubule asters. The ingression velocity was determined by fitting a slope to the mean of the ingression from the six embryos in the respective cell cycle phases. The error represents the error of the slope.

Microtubule orientation analysis

Microtubule orientation analysis was performed manually as well as by automatic orientation detection. For manual orientation analysis, microtubules were traced using the Fiji line tool. The length, start point, end-point and angle was measured for every line. Seven embryos were analysed, with in total 712 measurements pre-cut and 720 measurements post-cut, covering over 100 randomly selected microtubules per image. In Python, all measured lines from pre- and post-cut embryos were plotted into the same plots, respectively, using slightly transparent lines colour-coded by angle.

For the automatic orientation analysis, the OrientationJ68 plugin in Fiji was used. The parameters for microtubule orientation detection used were sigma: 5, Gradient: Gaussian, Grid size: 10, Length vector: Maximum, Scale vector 80. Three embryos were analysed before ablation and 20 frames (6 s) after laser ablation. The mean orientations of the three embryos were plotted using Python and the lines were colour-coded according to their angle. For one embryo, the orientation profile over time was plotted (Fig. 2c) using Wolfram Mathematica.

Magnetic tweezers analysis

For magnetic tweezers experiments beads were tracked using the Fiji plugin Trackmate69 v.7.12.1 (ref. 70). Trackmate parameters were stored in a table for every dataset, parameters were optimized to detect all beads in every time frame, to avoid gaps in tracks. False detections and detected beads outside region of interest were excluded. All parameters of the experiments (such as first magnet pulse, duration of pulse, duration of break, last pulse, presence of absence of microtubules, calibration of magnetic tip) were collected in a .csv file together with the file paths of the Trackmate data and further processed using Python71,72,73.

First, the distance from the tip was calculated for each bead for each time point. The tip was detected manually in Fiji. The magnetic tweezer pulses were 5 s and the relaxation period before the pulse was 15 s. Due to natural reorganization of the cytoplasm, slow flows were produced on the beads. We corrected the bead displacement curves by subtracting this spontaneous flow. The flow was measured during the last 5 s of relaxation period, before the next force pulse was applied. As the relaxation times of the system were estimated to be around 1 s (less than 2 s in almost all cases (Supplementary Fig. 4f)), we assumed that the system has completely relaxed in 10 s. We measured the total displacement of each bead for each pulse and normalized it with the average force produced on the bead during the pulse. After the magnetic tip was turned off, the beads partially returned to their original position. We measured this relaxation distance and defined recovery a as a ratio between the total displacement during the period with force applied and the relaxation during the period without external force.

We measured in total 827 individual tracks of beads across 12 embryos, of which 440 were measured in interphase and 387 were measured in M-phase. Number of tracks per embryo varies (Supplemenary Fig. 4l). As the magnetic force depends on the distance of the bead to the magnetic tip, the forces produced on beads were dispersed between 20 and 160 pN (Supplementary Fig. 4h,i). To compare bead responses between the phases across the same force range, we set the force range of interest to be between 20 pN and 60 pN, where most of the data for each phase lie. This leaves us with 674 full tracks (436 in interphase and 238 in M-phase) across 11 embryos (see Supplementary Fig. 4n for the distribution of tracks per embryo). Each bead went through on average 8 consecutive pulses and 17 at most, throughout which the measurements did not change significantly (Supplementary Fig. 4d,e).

We performed measurements in embryos treated with taxol and nocodazole, obtaining 211 tracks in 3 taxol-treated embryos and 154 tracks in 9 nocodazole-treated embryos in the 20 pN to 60 pN force range.

We analysed the normalized displacement and recovery a for each bead separately, as well as averaged response per each embryo. We report normalized displacement and recovery of the averaged curve. For comparison between conditions, we perform statistical analysis on the averaged curves, calculating P values with weighted unequal variance (Welch) t-test. Weights are calculated as the number of tracks per embryo, normalized with the total number of tracks and multiplied by the number of embryos, in each condition. We also report the weighted mean of the bootstrapped data (n = 1,000) and the 95% confidence interval.

Displacement curves were fitted with Jeffrey’s model for viscoelastic material. Jeffrey’s model consists of a Kelvin–Voigt element with a spring constant \(k\) and a dashpot with viscous damping coefficient \({\gamma }_{1}\), in series with another dashpot with a viscous damping coefficient \({\gamma }_{2.}\) This model predicts displacement of the bead \(x(t)\) to be

$$x(t)=\left\{\begin{array}{c}\frac{{F}_{0}}{k}\left(1-{{\rm{e}}}^{-\frac{{kt}}{{\gamma }_{1}}}\right)+\frac{{F}_{0}t}{{\gamma }_{2}},\,\text{for}\,t\le {t}_{p},\\ x({t}_{p})(a{{\rm{e}}}^{-\frac{{kt}}{{\gamma }_{1}}}-(1-a)),\,\text{for}\,t > {t}_{p},\end{array}\right.$$

where \({F}_{0}\) is an average force produced on the bead by the magnetic tweezers during the pulse of duration \({t}_{p}\). Recovery is calculated as

$$a=1-\frac{1}{1+\frac{{\gamma }_{2}}{k{t}_{p}}(1-{{\rm{e}}}^{-k{t}_{p}/{\gamma }_{1}})}.$$

We performed statistical analysis (same as above) on the fit parameters obtained from the averaged curves in each phase. The mean values for each parameter were calculated with the weighted bootstrapping method (n = 1,000, see results in Supplementary Fig. 4f,g,j,k) and used for the theoretical prediction of the band ingression (described below).

Optical tweezers analysis

The averaged interphase and M-phase G′ and G″ measurements show a typical dependence of frequency consistent with a Kelvin–Voigt fractional74, with functional form

$${G}^{* }(\omega )={c}_{\alpha }{(i\omega )}^{\alpha }+{c}_{\beta }{(i\omega )}^{\beta }$$

To compare M-phase and interphase material properties, we took the ratio of interphase to M-phase for G′ (and G″). This ratio is roughly constant for all frequencies (Supplementary Fig. 4b). To determine the fold change between interphase and metaphase, we bootstrapped the mean by taking the mean of randomly sampling with substitution from the total number of optical tweezers measurements in each condition, and then taking the mean of the ratio between conditions for low frequencies (between 0.5 and 16 Hz). We repeated this process n = 1,000 times to obtain a distribution of ratios, from which we obtain the mean fold change and 95% confidence intervals.

To further investigate the consistency between magnetic and optical tweezer measurements, we converted the magnetic tweezers creep compliance to G′ and G″ following Evans et al.35. In brief, we obtained the creep compliance from the averaged displacement curves (from eight embryos for each phase) of the magnetic tweezers experiments using \(J(t)=6{\rm{\pi }}{R\; x}(t)/f(t)\), where R is the bead radius, \(x(t)\) and \(f(t)\), the displacement and force applied to the bead respectively. Then, we applied the following expression to convert the creep compliance to G* (ref. 35):

$$\frac{i\omega }{{G}^{* }(\omega )}=i\omega \,J(0)+\frac{(1-{{\rm{e}}}^{(-i\omega {t}_{1})})[{J}_{1}-J(0)]}{{t}_{1}}+\frac{{{\rm{e}}}^{-i\omega {t}_{N}}}{\eta }+\mathop{\sum }\limits_{k=2}^{N}\left(\frac{{J}_{k}-{J}_{k-1}}{{t}_{k}-{t}_{k-1}}\right)({{\rm{e}}}^{-i\omega {t}_{k-1}}-{{\rm{e}}}^{-i\omega {t}_{k}}),$$

where \(J(0)\) is the compliance at \(t=0\), and \(\eta \) is the steady state viscosity which is the extrapolation of the compliance at \(t\to \infty \). To obtain \(J(0)\) and \(\eta \), we fit the magnetic tweezers curves to the phenomenological equation \(b+{a\; x}+c{{\rm{e}}}^{-{d}{x}}\), with \(J(0)=b+c\), and \(\eta =\frac{1}{a}\). We show the results for G′ and G″ of the weighted mean (bootstrapped n = 1,000) and the 95% confidence interval of the mean for 8 averaged creep responses for each phase (see section on magnetic tweezer image analysis).

Theory

The cell is modelled as a spherical mesh of viscoelastic edges, of radius 350 μm, generated with roughly uniform density of vertices using Gmsh75. Notably, the mesh is symmetric across the y–z plane, giving a line of springs around the equator, which will represent the band. Each edge is modelled by a Jeffrey’s viscoelastic material, with parameters estimated from experiments for M-phase and interphase. The band was modelled by adding contractile tension to edges, starting from the top of the cell and going around the equator, with the ends of the band growing over time. We simulate the system starting with no band, with interphase lasting 15 min and M-phase lasting 10 min, with the material properties of the edges dependent on the current phase. We measure the ingression of the band by the displacement of the highest point of the band.

Each edge within the mesh is modelled as a viscoelastic Jeffrey’s material, with parameters \(k=32.4\), γ1 = 56.1 s, and γ2 = 189.8 s in interphase, and \(k=21.4\), γ1 = 27.0 s, and γ2 = 41.7 s in M-phase, which were determined from the magnetic tweezers experiments. The constitutive equation for edge i is given by

$${\sigma }_{i}+\frac{{\gamma }_{1}+{\gamma }_{2}}{k}\dot{{\sigma }_{i}}={\gamma }_{2}\dot{{{\epsilon }}_{i}}+\frac{{\gamma }_{1}{\gamma }_{2}}{k}\ddot{{{\epsilon }}_{i}}$$

where \({\sigma }_{i}\) is the stress and \({{\epsilon }}_{i}=({l}_{i}-{l}_{i,0})/{l}_{i,0}\) is the strain, with length \({l}_{i}\) and initial length \({l}_{i,0}\). Each edge may also be under a contractile tension \({\lambda }_{i}={\Lambda }{p}_{i}\), where \({\Lambda }\) is the tension of the band, and \({p}_{i}\) is the proportion of the edge covered in the band ranging from 0 to 1. As we work with discrete elements, a band proportion between 0 and 1 represents an edge where the band only covers a fraction of it. Initially all edges have \({p}_{i}=0\).

We simulate the band growth and cell mechanics numerically, with time step \({\rm{d}}t=0.01\,\min \). During each time step, we first grow the band and then move the vertices such that forces are balanced. The band growth is modelled by sequentially increasing the band amount \({p}_{i}\) of edges around the middle of the cell, starting from the top, until the total length of added band equals our desired amount, through the following procedure

-

1.

Set the length of band to be added equal to \(G=g{\rm{d}}t\) where g = 25 μm min−1 is the growth speed of the band, estimated from PIV data.

-

2.

Starting from the centre of the band at \(\theta =0,\,\phi =0\), and going around the edges of \(\phi =0\) as \(\theta \) increases we attempt to add new band to the edge.

-

a.

If the band fully covers the band, \(p=1\), then we go to the next edge.

-

b.

If the amount of band to add is longer than the length available on the edge, \(G > (1-p)l\), then we set the edge to be fully covered by the band, \(p=1\), and reduce the amount of band to be added by \(G\to G-(1-p)l\).

-

c.

Otherwise, we added the remaining band to the edge, such that \(p=p+G/l\) and finish growing the band.

-

a.

-

3.

Repeat step 2 for the \(\phi ={\rm{\pi }}\) direction, so that the band grows from both ends.

Next, we find the force balanced state. We discretize the constitutive equation as

$${\sigma }_{i}({t}_{n-1})+\frac{{\gamma }_{1}+{\gamma }_{2}}{k}\left(\frac{{\sigma }_{i}({t}_{n})-{\sigma }_{i}({t}_{n-1})}{{\rm{d}}t}\right)={\gamma }_{2}\,\left(\frac{{{\epsilon }}_{i}({t}_{n})-{{\epsilon }}_{i}({t}_{n-1})}{{\rm{d}}t}\right)+\frac{{\gamma }_{1}{\gamma }_{2}}{k}\left(\frac{{{\epsilon }}_{i}({t}_{n})-{2{\epsilon }}_{i}({t}_{n-1})+{{\epsilon }}_{i}({t}_{n-2})}{{\rm{d}}{t}^{2}}\right)$$

where \({\sigma }_{i}({t}_{n})\) and \({{\epsilon }}_{i}({t}_{n})\) are the stress and strain of edge i at time \({t}_{n}=n{\rm{d}}t\). The strain at time step \(i\) is determined by the position of the edge’s vertices, which are in turn determined by force balance. The force acting on vertex j is

$${{\boldsymbol{f}}}_{j}=\sum _{i}({\sigma }_{i}+{\lambda }_{i})\hat{{{\boldsymbol{t}}}_{i}}$$

where we sum over all edges connected to the vertex and \({\hat{{\boldsymbol{t}}}}_{{i}}\) is the unit vector along the edge pointing away from the vertex. The vertices are then moved in the direction of the force by a small amount, and new strains, stresses, and forces are calculated, and this process repeated until the force is approximately balanced, determined when the maximum force over all vertices is less than 10−5.

Finally, we have one free parameter to fit the experimental data with, the band tension \(\varLambda \). To fit the experiments, we run simulations for a range of tensions, from 0 to 10, and select the tension with the lowest mean squared error between the predicted displacement in the model, and the mean measured displacement in experiments. We use a tension \(\varLambda =1.5\), which has a 99.4% R2 score against experimental data.

Statistics and reproducibility

Numbers of independent replicates of representative images (where not stated in figure legend).

-

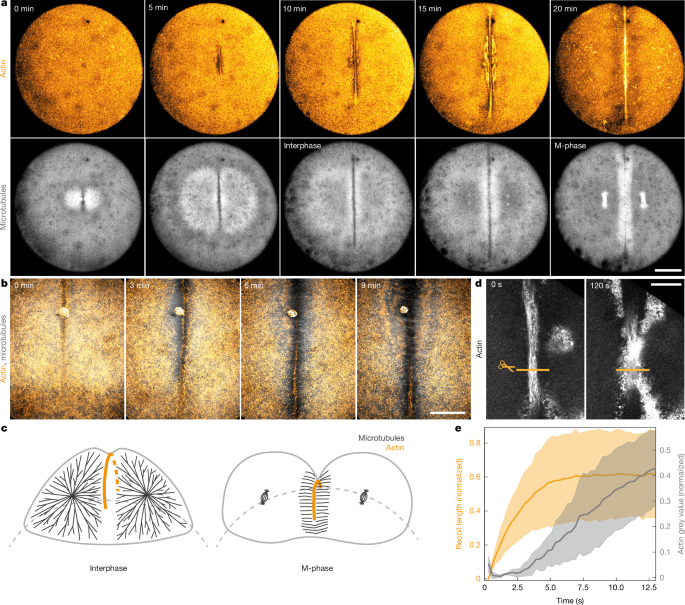

Fig. 1a: the band formation has been imaged in at least n = 15 individual embryos.

-

Fig. 1b: the band formation at this higher magnification (40× or more) has been imaged in at least n = 6 individual embryos.

-

Fig. 1d: the laser continuous laser ablation, over the time course of several minutes, has been repeated in at least n = 3 individual embryos, all demonstrating ingression of the remaining band that was not cut.

-

Fig. 2a: The microtubule splay upon laser ablation has been imaged in at least n = 10 individual embryos.

-

Fig. 2f: the band retraction upon microtubule depolymerization was repeated in at least n = 10 individual embryos.

-

Fig. 2g: the band separation with the obstacle was repeated in at least n = 2 individual embryos.

-

Fig. 3a: the band retraction in interphase arrested embryos experiment was repeated in at least n = 10 individual embryos.

-

Fig. 3b: the band retraction in interphase arrested embryos followed by microtubule depolymerization was repeated in n = 8 embryos.

Number of replicates of representative images in the Supplementary Figures.

-

Supplementary Fig. 1a: at least n = 10 individual embryo replicates (with confocal spinning disc imaging instead of light sheet).

-

Supplementary Fig. 1b: at least n = 15 individual embryo replicates

-

Supplementary Fig. 1c: the band formation at this higher magnification (40× or more) has been imaged in at least n = 6 individual embryos.

-

Supplementary Fig. 1d: the laser continuous laser ablation, over the time course of several minutes, has been repeated in at least n = 3 individual embryos, all demonstrating ingression of the remaining band that was not cut.

-

Supplementary Fig. 1e: the band ingression without laser ablation has been imaged in at least n = 6 individual embryos at this magnification.

-

Supplementary Fig. 2a: multiple subsequent cuts repeated in at least n = 3 embryos.

-

Supplementary Fig. 2c: the cortex was cut in at least n = 3 individual embryo replicates.

-

Supplementary Fig. 2d: the cortex and band were cut in at least n = 3 individual embryo replicates.

-

Supplementary Fig. 2e: Actin inhibition was imaged in at least n = 10 individual embryo replicates.

-

Supplementary Fig. 2f: The laser ablation upon wound-healing induction was imaged in at least n = 1 embryo.

-

Supplementary Fig. 3a: the taxol treatment at the shown concentration was repeated in n = 4 individual embryos, from the same batch of embryos.

-

Supplementary Fig. 3b: the taxol treatment at the shown concentration was repeated in n = 4 individual embryos, from the same batch of embryos.

-

Supplementary Fig. 3c,d show different z-slices of the same embryo. The band retraction in interphase arrested embryos experiment was repeated in at least n = 10 individual embryos.

-

Supplementary Fig. 5b: the ferrofluid droplet extension in untreated embryos was repeated at least n = 13 times in individual embryos.

-

Supplementary Fig. 5c: laser ablation of the contractile band to resolve wrinkles was performed at least n = 1 time in individual embryos.

-

Supplementary Fig. 5e: the demonstration of fluid region between asters was repeated at least n = 2 times in individual embryos.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.