Design and fabrication of the integrated modulator and modified UTC-PD

The TFLN modulator is fabricated on a 360-nm-thick X-cut single-crystalline LN thin film bonded on a 2.5-µm silicon dioxide layer sitting on a quartz substrate (NanoLN). First, the LN waveguides and multi-mode interference structures are patterned by positive resist by means of electron-beam lithography and etched by fluorine-based reactive ion etching. After the first lithography and etching, the LN waveguides with a sidewall angle of 72°, slab thickness of 180 nm and rib height of 180 nm are obtained. The slab is then patterned and etched to form the edge couplers. After patterning the LN waveguides and edge couplers, a plasma-enhanced chemical vapour deposition SiO2 film of thickness 1.2 µm is deposited as the cladding layer. Subsequently, a 180-nm-thick NiCr layer is deposited as the terminal resistor and on-chip terminator. Next a lift-off process produces the 1-µm-thick gold transmission lines and DC electrodes. Finally, the device end face is diced, lapped and polished to achieve improved end-face coupling efficiency. The fabrication also complies with standard lithography and etching techniques available in a typical foundry, ensuring process reproducibility and potential for scalability.

The epitaxial structure of the modified UTC-PD is designed for high-speed and high-power operation. The 180-nm InGaAs absorption layer includes an 80-nm undepleted region with a step-graded profile (5 × 1017, 1 × 1018 and 2 × 1018 cm−3) to form a quasi-electric field that assists electron transport and the remaining 100 nm is depleted to establish a high electric field across the InGaAs/InP heterojunction. Beneath the absorber, a 220-nm slightly n-doped (1 × 1016 cm−3) InP drift layer is incorporated to support high-speed carrier transit. A 30-nm heavily doped (2 × 1017 cm−3) InP cliff layer is inserted between the absorber and the collector to sustain an electric field of 20–50 kV cm−3 in the drift layer to support electron velocity overshoot, thereby accelerating electron transmission and extending device bandwidth. The implementation of the cliff layer also greatly reduces the conduction band barrier across the heterojunction in the depletion region, thus suppressing carrier pile-up under high optical input and improving high-power performance. To further suppress parasitic capacitance and enhance RC-limited bandwidth, a 4-µm-thick benzocyclobutene dielectric layer is introduced beneath the coplanar waveguide electrodes, improving electrical isolation and device robustness. Moreover, the InP drift layer is extended outward to serve as the upper cladding of the InGaAsP waveguide, ensuring uniform optical absorption and mitigating localized saturation under strong light injection. Also, the thickness and refractive index of the 400-nm InGaAsP waveguide layer is carefully engineered to enable efficient and smooth evanescent light coupling into the absorber. This results in a more evenly distributed light absorption and carrier generation profile across the absorber, which mitigates localized saturation and enables higher output power under strong light injection.

The fabrication of the modified UTC-PD begins with the epitaxial growth on a 2-inch semi-insulating InP substrate using metal–organic chemical vapour deposition. The epilayers are similar to the structure in ref. 17. Ti/Pt/Au metal layers are then deposited to form the p-type ohmic contacts. The triple-mesa structure of the device is defined through a combination of inductively coupled plasma dry etching and selective wet etching. The etch process is precisely controlled to ensure accurate patterning, enabling close agreement between optical simulations and the fabricated device. Subsequently, Ge/Au/Ni/Au layers are deposited to form the n-type ohmic contacts, followed by rapid thermal annealing at 360 °C to enhance contact performance. Finally, a 3-µm-thick layer of benzocyclobutene is applied to provide passivation and mechanical support, following which Ti/Au coplanar waveguides are deposited to connect the electrodes to the PD contacts. The process flow uses a standard III–V semiconductor process and is compatible with wafer-scale manufacturing.

Characterization of the EO/OE response of the TFLN modulator and modified UTC-PD

We use a function waveform generator (RIGOL DG922 Pro) to generate a 100-kHz triangular voltage sweep and measure the Vπ,LF as 5.1 V by a digital oscilloscope (RIGOL DHO1202U). The Vπ,RF can then be calculated using:

$${V}_{{\rm{\pi }},{\rm{RF}}}={V}_{{\rm{\pi }},{\rm{LF}}}\times {10}^{-\frac{\text{EO}{S}_{21}}{20}}$$

(1)

As for the EO bandwidth characterization, measurements are conducted in three steps. First, a vector network analyser (Keysight N5222B) equipped with a millimetre test set (Keysight N5292A) and a LCA (Keysight N4372E) is used to generate and analyse frequency signals below 110 GHz. For higher frequencies, THz signals >110 GHz are generated by upconversion. The 250-kHz to 20-GHz signals (Keysight E8257D) are upconverted by frequency multipliers into the 110–170-GHz band (NZJ SGFE06) and the 140–220-GHz band (NZJ SGFE05) and then delivered to the TFLN modulator by means of matched ground–signal–ground (GSG) probes. EO response is measured by tracking the power ratio between the sideband and the carrier at each frequency using an optical spectrum analyser (OSA; Yokogawa AQ6370D). The normalized sideband power Pn is defined as:

$${P}_{{\rm{n}}}=\frac{{P}_{{\rm{carrier}}}}{{P}_{{\rm{sideband}}}}$$

(2)

The Vπ,RF at each frequency can be calculated directly using equation (3) (ref. 50):

$${V}_{{\rm{\pi }},{\rm{RF}}}=\frac{1}{4}{\rm{\pi }}{V}_{{\rm{p}}}\sqrt{{P}_{{\rm{n}}}}$$

(3)

in which Vp denotes the maximum voltage of the input THz signal. The EO response can be derived from equations (1)–(3) as:

$${\rm{EO}}\,{S}_{21}=-20\times \log \left(\frac{{\rm{\pi }}}{4{V}_{{\rm{\pi }},{\rm{LF}}}}\right)-20\times \log ({V}_{{\rm{p}}})-{P}_{{\rm{c}}}+{P}_{{\rm{s}}}$$

(4)

The first term of equation (4) represents the constant term related to Vπ,LF. The second term is the drive power delivered to the modulator and can be calculated by subtracting the probe loss from the output power of the frequency multipliers. Pc and Ps are the carrier and sideband power, respectively, measured from the OSA corresponding to each test point. After de-embedding the difference of the driving power at each test frequency, the EO response is proportional only to the carrier and sideband amplitudes. Because the probes and frequency multipliers have been precisely measured and calibrated, the primary source of measurement uncertainty lies in the power uncertainty of the OSA. According to the operation manual, the power measurement uncertainty of the OSA is ±0.4 dBm, resulting in a bandwidth measurement uncertainty of ±0.4 dB from 110 to 220 GHz. The calculated results for the 110–170-GHz and 140–220-GHz bands are first normalized by their overlapping-region average and then referenced to the 110-GHz data from the LCA.

The frequency response and saturation behaviour of the modified UTC-PD are characterized using an optical heterodyne set-up. Two tunable lasers with wavelengths λ1 and λ2 are combined to generate a tunable beat frequency fbeat by fixing one wavelength and tuning the other. Polarization controllers ensure optimal alignment, enabling nearly 100% modulation depth. The combined optical signal is amplified by an erbium-doped fibre amplifier (EDFA) and then coupled into the chip. A DC bias is applied to the device using a source meter (Keysight B2901A).

$${f}_{{\rm{beat}}}={f}_{1}-{f}_{2}=\frac{c}{{\lambda }_{1}}-\frac{c}{{\lambda }_{2}}$$

(5)

For RF measurements, the RF signal generated by the UTC-PD is directly measured by a power meter through a GSG probe. Under 100% modulation depth, the ideal RF output power follows equation (6) with RL = 50 Ω, corresponding to the purple reference line in Fig. 2e. Different measurement set-ups are used for different frequency ranges to ensure accurate power measurement. From DC to 110 GHz, output power is measured using a power meter (Rohde & Schwarz NRP2) connected through a GSG 110-GHz probe. Cable, bias-tee and probe losses are calibrated with a vector network analyser and appropriate calibration kits (85059B and CS-5). For frequencies above 110 GHz, a THz power meter (VDI PM5B) and corresponding waveguide probes (110–325 GHz) are used. Losses from waveguide tapers and probes are de-embedded using data provided by the manufacturer.

$${P}_{{\rm{ideal}}}=\frac{1}{2}{R}_{{\rm{L}}}{I}_{{\rm{ph}}}^{2}$$

(6)

Details of data transmission experiments

For short-reach IMDD experiments, periodic pseudorandom bit sequence signals are generated by an AWG (Keysight M8199B, approximately 75-GHz analogue bandwidth) and shaped with a raised cosine filter. An electrical power amplifier (SHF T850 C, 100-GHz analogue bandwidth) is needed to compensate for the degradation brought by the cables and probes. After amplification, the TFLN modulator encodes the 1,550-nm optical carrier into NRZ and PAM-4 formats at symbol rates from 112 to 256 Gbaud. An EDFA (Amonics AEDFA-C-DWDM) is used to boost the modulated optical signal. At the Rx side, the modulated signals are first converted and recorded by a DSO (Keysight N1000A) with a 120-GHz optical sampling module (Keysight N1032A). We apply no bandwidth compensation DSP and take screenshots of the eye diagrams to show the intrinsic UWB features of our TFLN modulator. The transmission capacity can be further improved using feed-forward equalizer and other equalization algorithms. We also use a 70-GHz-bandwidth RTO (Keysight UXR0702AP) with a 110-GHz PD (Coherent XPDV4121R) to obtain the real transmission data. After resampling and synchronization, the collected data are fed into the network for signal recovery. Finally, the output signal from the complex-biGRU algorithm undergoes signal decision-making and BERs are calculated to assess the system performance.

For high-speed wireless coherent optical transparent relaying demonstration, the optical baseband signal is generated by a commercial silicon coherent transmitter with a bandwidth of around 35 GHz and a laser source operating at the fixed wavelength of 1,550 nm. IQ signals of different symbol rates are generated by an AWG and mapped to QPSK, 16-QAM and 32-QAM symbols. A tunable ECL (TOPTICA CTL 1550) with 180-GHz frequency offset from 1,550 nm serves as the Tx LO, which is attenuated to the same power as the signal light and combined with the signal light by means of a 50:50 coupler. The mixed signals are amplified by an EDFA and coupled into the modified UTC-PD, in which the baseband signal is shifted to the 180-GHz-centred THz signal by heterodyne beating. Two 140–220-GHz horn antennas (Anteral SGH-26-WR05) with 26-dBi gain are placed at a distance of 20 cm for THz emitting and receiving. A 145–220-GHz LNA (Fintest FTHZLNA-05FB) with 24-dB gain is used at the output of the Rx antenna to amplify the attenuated THz signal, which subsequently drives the TFLN modulator and converts onto an optical carrier with the wavelength of 1,550 nm. Before EDFA amplification, the optical carrier is filtered out by a tunable FBG filter (AOS Tunable FBG) to take full advantage of the available gain of the EDFA. The output from the EDFA is sent into the optical modulation analyser (Keysight N4391B) as the signal light. Another tunable ECL acting as the Rx LO is set to be the same wavelength as the Tx LO. The data are then collected and analysed offline using different DSP techniques. For 4-m wireless transmission, we replace the original horn antennas with 40-dBi-gain lens antennas while keeping the rest of the link unchanged.

In the baseline DSP chain at the receiver, Gram–Schmidt orthogonal normalization is first performed, followed by matched filtering and downsampling. Adaptive equalization and carrier recovery are then implemented. Subsequently, frequency offset is estimated, in which the tap coefficients of the equalizer are pre-converged using the constant modulus algorithm. Afterwards, carrier phase estimation is performed within the decision-directed least mean square update loop using the blind phase search algorithm. Finally, another orthogonalization is applied. For the complex-biGRU processing chain, the equalized signal from baseline DSP is used as the input signal and fed into the GRU network for further equalization. Symbol decisions are determined and BERs are calculated after each DSP chain.

For multichannel real-time videos transmission, two Ethernet-optical switches (FS S3950-4T12S-R) are used for signal routing and distribution. The computers connect to the Tx/Rx switch through Ethernet ports under the IEEE 802.3ab protocol. Owing to the fixed 10-GHz bandwidth limitation of the Rx FBG filter, the carrier spacing between two simultaneously transmitted video signals must exceed 10 GHz to avoid signal aliasing. Therefore, we select two SFP+ modules (FC DPP1-5592-81Y1) with 17-GHz wavelength spacing as the transmitters.

Details of the complex-biGRU algorithm

Wireless communication, especially higher-order wireless coherent communication, sustains more severe nonlinear effects caused by reflection, diffraction and scattering in the free space. Various nonlinear equalizers have been proposed to mitigate these repercussions32,37, among which NN-based methods outperform others on dealing with complicated disturbance. However, although NN-based equalizers have demonstrated effectiveness in reducing the BER, the ‘jail window’ pattern often arises simultaneously (Supplementary Note 5). Such phenomenon will change the signal distribution away from a Gaussian distribution, leading to serious deterioration of FEC coding51.

The proposed complex-biGRU network implements a five-layer structure. The first layer is the input layer. For coherent optical communication, each symbol rn can be separated into In and Qn. The second layer is the complex-biGRU layer. Given that the M-QAM modulation format encompasses both in-phase (I) data and quadrature (Q) data, the complex-biGRU layer is designed to process the I and Q data in parallel. In each biGRU network, the model with the bidirectional structure is determined by the combined states of two GRUs, which are unidirectional in opposite directions. One GRU processes the data from the start of the sequence and the other GRU processes the data from the end of the sequence. The outputs of the complex-biGRU layer are fully connected to a linear layer, followed by a multilevel layer serving as the nonlinear activation function. Finally, the predicted output can be expressed as the summation of the two-path outcomes. For IMDD signals, only one path of the network is activated to reduce computational expenditure of the system, whereas the remaining processes are the same as those for coherent signals.

Traditional activation functions typically exhibit two saturation regions. Nevertheless, for higher-order modulation formats, the equalizer equipped with an activation function featuring two saturation regions demonstrates insufficient effectiveness. The signal equalization problem can be considered as a classification problem, in which the output of a multilevel signal needs to be categorized into several classes. Therefore, an activation function with several saturation regions will greatly boost the performance of the system. The activation function applied in our algorithm is defined as52:

$$f(x)\,=\,\frac{2{\alpha }_{2}}{1+{{\rm{e}}}^{-{\alpha }_{1}(x-2\mu )}}-{\alpha }_{2}+2\mu \,{\alpha }_{2}\,=\,\frac{1+{{\rm{e}}}^{-{\alpha }_{1}}}{1-{{\rm{e}}}^{-{\alpha }_{1}}}$$

(7)

in which α1 represents the gradient factor and α2 is devised to ensure the continuity of the function. For four-level signal equalization scenarios such as PAM-4 and 16-QAM, µ assumes values of −1, 0 and 1 when x ≤ −1, −1 < x ≤ 1 and x > 1, respectively. Similarly, to accommodate PAM-6 and 32-QAM signals, µ can be adjusted to −2, −1, 0, 1 and 2 when x ≤ −3, −3 < x ≤ −1, −1 < x ≤ 1, 1 < x ≤ 3 and x > 3, respectively.

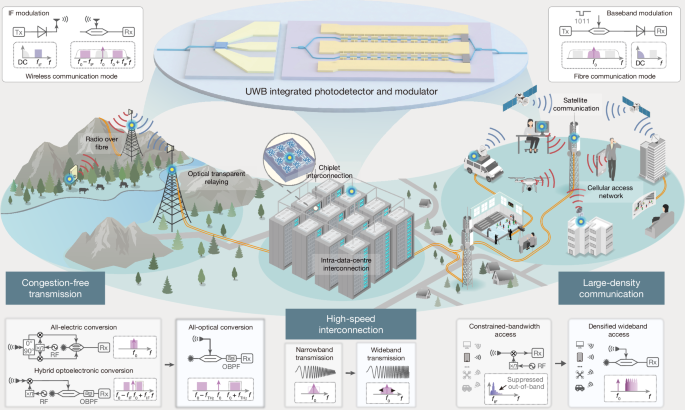

Comparison of the UWB integrated photonics system

The proposed UWB integrated photonics system achieves exceptional performance for both the device and system levels. To be more specific, we summarize the representative results in recent years and conduct detailed comparison analyses with them. Extended Data Table 1 shows the comparison of integrated EO Mach–Zehnder modulators (MZMs) operating in the C band on different material platforms with different structures. Our modulator achieves double the bandwidth compared with most other devices while maintaining high modulation efficiency and ultralow insertion loss. We also calculate the slope efficiency of the modulator using following equation:

$$\mathrm{Slope}\,\mathrm{efficiency}=20\times \log \,\left(\frac{T}{{V}_{{\rm{\pi }},{\rm{R}}{\rm{F}}}}\right)$$

(8)

in which T is the optical transmittance before and after the modulator in linear units. Our modulator realizes comparable slope efficiency while operating at twice the bandwidth. Although plasmonic modulators have demonstrated nearly 1-THz EO bandwidth, they simultaneously suffer from high optical insertion loss and prohibitively large half-wave voltage, as well as fluctuating EO response, limiting their performance in practical applications.

Extended Data Table 2 presents a comparison of integrated high-speed OE photodetectors across different material platforms and epitaxial structures. At the material level, although Ge-based PDs have achieved impressive bandwidths (for example, 265 GHz), they typically operate under low optical power owing to the limited electron saturation velocity in Ge (about 5 × 106 cm s−1), which restricts current handling at high frequencies and application for THz generation. By contrast, InP offers a higher electron saturation velocity (about 2 × 107 cm s−1), enabling better current handling capability, making it the preferred material for high-speed, high-power photodetectors beyond 100 GHz. From a structural perspective, UTC-PDs exhibit superior saturation characteristics over conventional PIN PDs by rapidly collecting slow-mobility holes and enabling electron-only drift. This design mitigates space-charge effects under high optical injection, thus supporting higher photocurrents and THz output power. Among the InP-based waveguide-coupled PDs, our modified UTC-PD exhibits a higher OE bandwidth than previous works while maintaining high THz output power, along with a decent responsivity of 0.24 A W−1. These well-balanced metrics position it as a compelling solution for next-generation ultra-broadband telecommunication systems.

Extended Data Table 3 shows the comparison of the integrated IMDD communications. Our approach demonstrates the highest transmission rate without any bandwidth compensation DSP. We also achieve the highest symbol rate of 256 Gbaud and the highest PAM-4 data rate of 512 Gbps with the complex-biGRU algorithm, reaching the limit of our test system. On the basis of these results, 479 Gbps (=512/(1 + 0.07)) net bit rate using conventional PAM-4 modulation can be calculated, achieving performance comparable with advanced PS-PAM-16 formats.

Extended Data Table 4 shows the comparison of the high-speed THz wireless communications based on different approaches. Our system is prominent in both single-channel symbol rate and single-channel data rate using the complex-biGRU algorithm. Even with the baseline DSP method, our system still achieves the highest single-channel symbol rate and data rate. We also calculate the carrier utilization efficiency, defined as the single-channel data rate divided by the carrier frequency, to evaluate the information-carrying ability of the carrier without any multiplexing techniques. Theoretically, a higher carrier frequency enables larger transmission capacity. Our system achieves the highest carrier utilization efficiency of 2.22, tripling the performance of previous systems. Besides single-channel performance, we also investigate multichannel capabilities across different THz wireless communications methods. As shown in the last column, the number of channels is used to characterize the multichannel performance of the system. Our solution achieves the maximum number of transmission channels of 86 channels with 1-GHz channel bandwidth, demonstrating exceptional large-density-access performance.