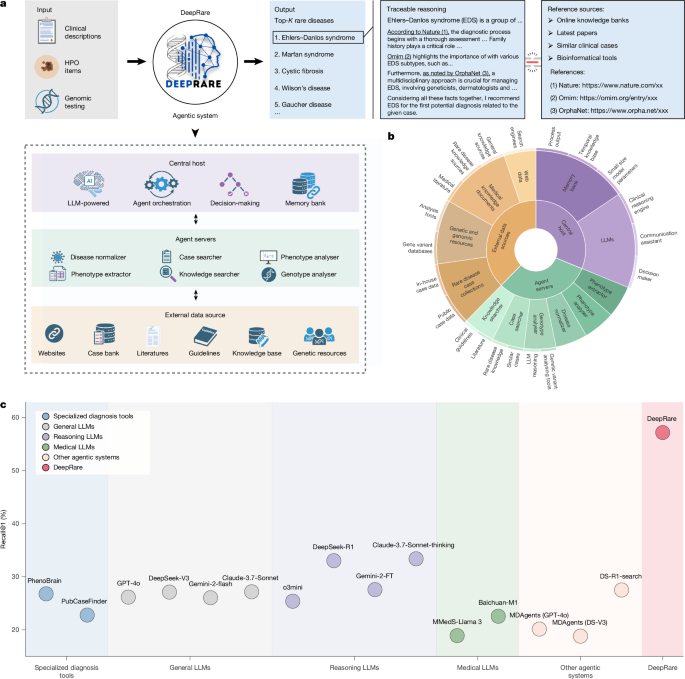

We introduce DeepRare—an agentic framework designed to support rare disease diagnosis, structured upon a modular, multi-tiered architecture. The system comprises three core components: (1) a central host agent, equipped with a memory bank that integrates and synthesizes diagnostic information while coordinating system-wide operations; (2) specialized local agent servers, each interfacing with specific diagnostic resource environments through tailored toolsets and (3) heterogeneous data sources that provide critical diagnostic evidence, including structured knowledge bases (for example, research literature, clinical guidelines) and real-world patient data. The architecture of DeepRare is described in a top-down manner, beginning with the central host’s core workflow and proceeding through the agent servers to the underlying data sources.

Problem formulation

In this paper, we focus on rare disease diagnosis, where the input of a rare disease patient’s case consists typically of two components: phenotype and genotype, denoted as \(\mathcalI=\\mathcalP,\mathcalG\\). Either \(\mathcalP\) or \(\mathcalG\) (but not both) may be an empty set ∅, indicating the absence of the corresponding input. Specifically, the input phenotype may consist of free-text descriptions \(\mathcalT\), structured HPO terms \(\mathcalH\) or both. Formally, we define, \(\mathcalP=(\mathcalT,\mathcalH)\), where either \(\mathcalT\) or \(\mathcalH\) may be empty (that is, \(\rm\varnothing \)) indicating the absence of that input modality. The ‘genotype input’ denotes the raw VCF file generated from WES.

Given \(\mathcalP\), the goal of the system is to produce a ranked list of the top \(K\) most probable rare diseases, \(\mathcalD=\d_1,d_2,\ldots ,d_K\\), and a corresponding rationale \(\mathcalR\) consisting of evidence-grounded explanations traceable to medical sources such as peer-reviewed literature, clinical guidelines and similar patient cases. This can be formalized as:

$$\\mathcalD,\,\mathcalR\=\mathcalA(\mathcalP),$$

(1)

where \(\mathcalA(\cdot )\) denotes the diagnostic model.

As shown in Extended Data Fig. 1b, our multi-agent system comprises three main components:

-

(1)

A central host with a memory bank serves as the coordinating brain of the system. The memory bank is initialized as empty and updated incrementally with information gathered by agent servers. Powered by a LLM, the central host integrates historical context from the memory bank to determine the system’s next actions.

-

(2)

Several agent servers execute specialized tasks such as phenotype extraction and knowledge retrieval, enabling dynamic interaction with external data sources.

-

(3)

Diverse data sources serve as the external environment, providing crucial diagnostic evidence from PubMed articles, clinical guidelines, publicly available case reports and other relevant resources.

Main workflow

The system operates in two primary stages, orchestrated by the central host: information collection and self-reflective diagnosis, as illustrated in Extended Data Fig. 1c. For clarity, the specific functionalities of the agent servers involved in each stage are detailed in the following section.

Information collection

In the information collection stage, the system pre-processes the patient input and invokes specialized agent servers to gather relevant medical evidence from external sources. The process begins with two parallel steps: one focusing on phenotype inputs and the other on genotype data. Subsequently, the central host takes control to facilitate diagnostic decision-making and patient interaction.

Phenotype information collection

Given the phenotype input (\(\mathcalP=(\mathcalT,\mathcalH)\)), the system performs the three main sub-steps to collect extra information: HPO standardization, phenotype retrieval and phenotype analysis.

In HPO standardization, the phenotype extractor \(a_\textHPO\) agent server is called, to convert the given free-form reports \(\mathcalT\) into a list of standardized entities \(\mathcalH\), denoted as:

$$\hat\mathcalP=\left\{\beginarraylla_\mathrmHPO(\mathcalT\,), & \mathrmif\,\mathcalT\ne \rm\varnothing \\ \mathcalH, & \mathrmotherwise\endarray\right.$$

(2)

As a result, each patient is now denoted as a set of standardized HPO entities (\(\hat\mathcalP\)) that are further treated as the query for phenotype retrieval.

The knowledge searcher (ak-search) and case searcher (ac-search) agent servers are invoked to retrieve supporting documents from the Web and relevant cases from an external database, respectively:

$$\mathcalE_\mathrmHPO=a_\rmk-\mathrmsearch(\hat\mathcalP,\mathcalM,N)\cup a_\rmc-\mathrmsearch(\hat\mathcalP,\mathcalM,N),$$

(3)

where \(\mathcalE_\mathrmHPO\) refers to a unified set of retrieved evidences and \(N\) denotes the search depth. Notably, the two search agents will also check the memory bank (\(\mathcalM\)) to avoid retrieving items that have already been recorded.

Finally, in phenotype analysis, the agent server integrates various distinct bioinformatics tools to provide a set of diagnostic-related suggestions, for example, identifying diseases that are more likely to be associated with the patient based on their phenotype, denoted as:

$$\mathcalY_\mathrmHPO=a_\mathrmHPO-\mathrmanalyzer(\hat\mathcalP)$$

(4)

Thus far, we have gathered relevant information on the phenotype by exploring the Web or database with similar cases, and several existing bioinformatics analysis tools, collectively denoted as \((\mathcalE_\mathrmHPO,\mathcalY_\mathrmHPO)\) and update them into the system memory bank \(\mathcalM\), denoted as:

$$\mathcalM\leftarrow \mathcalM\cup (\mathcalE_\mathrmHPO,\mathcalY_\mathrmHPO)$$

(5)

Following the phenotype analysis, the central host generates a tentative diagnosis based on the available phenotype information:

$$\mathcalD^\prime =\mathcalA_\mathrmhost(\hat\mathcalP,\mathcalM_5)$$

(6)

where <prompt>5 is a diagnosis-related prompt instruction to drive the central host. The output \(\mathcalD^\prime \) is an initialized rare disease list.

Genotype information collection

In parallel to the phenotype analysis, the system will also collect external information relevant to the genotypes, if provided (\(\mathcalG\ne \rm\varnothing \)). It also consists of three main sub-steps: VCF annotation, variant ranking and synthetic analysis. The first two steps are conducted by the genotype analyser agent server, and the last one is processed by the central host.

In VCF annotation, the goal is to annotate the raw VCF input, which often contains thousands of gene variants using various genomic databases. This process enriches each variant with comprehensive functional annotations, population frequencies and pathogenicity predictions. Subsequently, variant ranking is performed to prioritize variants on the basis of their potential clinical significance. This step applies scoring algorithms that consider several factors, including functional impact, allele frequencies, conservation scores and predicted pathogenicity:

$$\hat\mathcalG=a_\mathrmgeno-\mathrmanalyser(\mathcalG)$$

(7)

where \(\hat\mathcalG\) denotes the ranked set of variants ordered by their clinical relevance scores.

Finally, in synthetic analysis, the central host uses LLM to interpret the ranked variants and patient information, providing comprehensive variant interpretation, gene-phenotype association predictions and inheritance pattern analysis:

$$\mathcalD^\prime\prime =\mathcalA_\mathrmhost(\hat\mathcalG,\mathcalM,\mathcalD^\prime ,N_6)$$

(8)

where <prompt>6 is synthetic analysis prompt. If genotype data is not available (\(\mathcalG=\rm\varnothing \)), the system uses the phenotype-only diagnosis:

$$\mathcalD^\prime\prime =\mathcalD^\prime \mathrmif,\mathcalG=\rm\varnothing $$

(9)

where \(\mathcalD^\prime\prime \) represents the updated diagnosis list after incorporating genotype information (when available). The results are then consolidated and updated in the system memory bank:

$$\mathcalM\leftarrow \mathcalM\cup \mathcalD^\prime\prime $$

(10)

Self-reflective diagnosis

At this stage, the central host takes entire system control and proceeds to self-reflective diagnosis, which attempts to make a diagnosis based on all previously collected information.

Specifically, the central host will make a tentative diagnosis decision-making, defined as:

$$\mathcalD^\prime =\mathcalA_\mathrmhs(\hat\mathcalI,\mathcalM\,_7)$$

(11)

where <prompt>7 is a self-reflection prompt, and \(\mathcalD=\d_1,d_2,\ldots \\) represents the ranked list of possible rare diseases, ordered by their likelihood. Notably, if \(\mathcalD=\rm\varnothing \), that is, all proposed rare diseases are ruled out during self-reflection, the system will return to the beginning and increase \(N\) by \(\Delta N\), re-collect new patient-wise information and iterate through the entire program workflow until \(\mathcalD\ne \rm\varnothing \) is satisfied.

Once the system passes the former self-reflection step, the central host will further synthesize the collected information, and provide traceable, transparent rationale explanations:

$$\\mathcalD,\mathcalR\=\mathcalA_\mathrmhpo(\mathcalD,\hat\mathcalI,\mathcalM| < \mathrmprompt > _8)$$

(12)

where \(\mathcalR\) denotes the rational explanation for each output rare disease, organized as free-text by the central host. This ensures that the final diagnosis is not only accurate but also interpretable, offering users a clear and auditable justification for the predicted diseases. Notably, \(\mathcalR\) provides accessible reference links to enable traceable reasoning. Before producing the final output, we apply a post-processing step, namely reference link verification, which checks the validity of each URL and removes any invalid URLs from \(\mathcalR\) to mitigate hallucination (implementation details are provided in the Supplementary Information section 1.3).

Agent servers

Agent servers form the second tier of our DeepRare system. Each manages one or several specific tools, interacting with a specialized working environment to gather evidence from external data sources. Specifically, the following agent servers are used in our system: phenotype extractor, disease normalizer, knowledge searcher, case searcher, phenotype analyser and genotype analyser.

Phenotype extractor

The clinical rare disease diagnosis procedure requires converting patients’ phenotype consultation records (\(\mathcalT\)) into standardized HPO items. Specifically, we extract potential phenotype candidates and modify the phenotype name by prompting an LLM:

$$\mathcalH=\varPhi _\mathrmLLM(\varPhi _\mathrmLLM(\mathcalT\,| < \mathrmprompt > _9)_10)$$

(13)

where \(\mathcalH=\h_1,h_2,\ldots \\) denotes the set of extracted, unnormalized HPO candidate entities, and <prompt>9 and <prompt>10 represent the corresponding prompt instruction. Here, the two-step reasoning process is designed to extract more accurate phenotypic descriptions with LLM assistance, significantly reducing the probability of errors in the subsequent step.

Subsequently, we perform named-entity normalization leveraging BioLORD47—a BERT-based text encoder—to map these candidate entities to standardized HPO terms. Specifically, we compute the cosine similarity between the text embeddings of the predicted entity name and all standardized HPO term names. The top-matching HPO term is then selected to represent the entity. Notably, if no HPO term achieves a cosine similarity of 0.8 or above, the entity is discarded. To assess the effectiveness of this module, we provide a detailed comparison of phenotype extraction methods in Supplementary Information section 1.6.

Disease normalizer

During the diagnostic process, free-text diagnostic diseases are mapped to standardized Orphanet or Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) items, as more precise keywords for subsequent searches. Similar to that in the phenotype extractor, we use BioLORD47 to perform named-entity normalization, by computing the cosine similarity between the text embeddings of the predicted disease name and all standardized disease names listed in the Orphanet or OMIM. The top-matched standardized disease name is then used and, if all standardized disease names cannot match the predicted term (cosine similarity less than 0.8), the predicted disease will be discarded.

Knowledge searcher

The knowledge searcher is tasked with real-time knowledge document searching, interacting with external medical knowledge documents and the Internet, supporting the diagnosis system with latest rare disease knowledge.

When invoked, it will perform two distinct search modules with several searching tools, on a specific search query (Q), for example, HPO or predicted diseases:

-

(1)

General Web search. This part executes the general search engines, including Bing, Google and DuckDuckGo. We will call them one by one, following the listed order. Each time, the top-N Web pages (with a default value of N = 5) will be retrieved. Specifically, Bing (https://www.bing.com/) is accessed through automated browser simulation using Selenium, whereas Google (https://google.com) and DuckDuckGo (https://api.duckduckgo.com/) are queried through their official APIs. If a search engine completes the execution successfully, the process will stop immediately.

-

(2)

Medical domain search. Considering that some professional medical-specific Web pages may not be ranked highly in general search engines, this part retrieves information from well-known medical databases. The following search engines are considered:

Similarly, while searching academic papers and rare disease-specific knowledge bases, we retrieve the top-N Web pages (defaulting to N = 5) from each source. The search engines are queried one by one, and the process stops upon successful execution.

These tools retrieve Web pages and return them to the knowledge searcher, and are summarized by the agent server with a lightweight language model (GPT-4o-mini by default), to simultaneously extract key information and filter relevant content. This integrated processing pipeline can be formalized as:

$$\mathcalR=\varPhi _\mathrmLLM(\mathrmdocument,\mathcalQ| < \mathrmprompt > _11)$$

(14)

where \(\mathcalR\) represents the processed output for each retrieved document and \(\mathcalQ\) denotes the given search queries, and is the unified prompt instruction that simultaneously governs both summarization and relevance filtering. The system uses a binary classification approach: medical-related documents are retained and translated into the target language, whereas non-medical content is rejected with the output ‘Not a medical-related page’.

Case searcher

Inspired by clinical practice, where physicians often refer to publicly discussed cases when faced with rare or challenging patients, the case searcher agent is designed to explore an external case bank. Each patient in the database is represented as a list of HPO terms, transforming case search into an HPO similarity matching problem. Using an input HPO list (\(\mathcalH\)) from the query case, we implement a two-step retrieval method to interact with this external database. (1) Initial retrieval: we use OpenAI’s text-embedding model (text-embedding-3-small) to encode both the query HPO list and each candidate patient’s HPO representation into dense vector embeddings. The embeddings for all candidate patients in the case database have been pre-computed and stored using the same embedding model. We then identify the top-50 candidate patients based on cosine similarity between these embeddings. (2) Re-ranking: we further re-rank these candidates using MedCPT-Cross-Encoder52—a BERT-based model specifically trained on PubMed search logs for biomedical information retrieval. This model computes refined cosine similarity scores between the query case’s HPO profile and each candidate’s HPO profile, leveraging domain-specific medical knowledge to improve matching accuracy.

We also evaluated alternative retrieval strategies, including single-stage methods with different embedding models such as BioLORD and MedCPT, as well as traditional approaches such as BM2553 discussed above. Experimental findings indicate that the two-stage retrieval approach outperforms all alternatives, optimizing both computational efficiency and clinical relevance of the retrieved cases.

Similar to the knowledge searcher, after receiving the similar cases, the case searcher will further assess their relevance to prevent misdiagnosis from irrelevant cases, powered by the lightweight language model:

$$r_\mathrmcase=\varPhi _\mathrmLLM(\mathrmCase,\mathcalH| < \mathrmprompt > _12)$$

(15)

where \(r_\textcase\in \\textTrue,\textFalse\\) is a binary scalar that indicates whether the case is related to the given HPO list and <prompt>12 is the corresponding prompt instruction. Consistency is maintained by using the same LLM architecture used in the diagnostic process for this assessment.

Phenotype analyser

This agent server controls various professional diagnosis tools that have been developed for phenotype analysis. By integrating the analysis results from these tools into the overall diagnostic pipeline, our system is able to incorporate more professional and comprehensive suggestions. Specifically, given the patient HPO list (\(\mathcalH\)), the following tools are used:

-

PhenoBrain28: this is a tool for HPO analysis that takes structured HPO items as input (\(\hat\mathcalH\)) and outputs five potential rare disease suggestions. We adopt it by calling its official API (https://github.com/xiaohaomao/timgroup_disease_diagnosis/tree/main/PhenoBrain_Web_API).

-

PubcaseFinder29: this tool performs HPO-wise diagnostic analysis by matching the most similar public cases from PubMed case reports. Similarly, it takes the structured HPO items \(\hat\mathcalH\) as input and returns top-5 potential rare disease suggestions, each with a confidence score. We access it through its official API (https://pubcasefinder.dbcls.jp/api).

-

Zero-shot LLM inference: we also use LLMs to perform zero-shot preliminary reasoning. Given the extensive knowledge base acquired during LLM training, these models can often suggest candidate diagnoses that conventional diagnostic tools might overlook. Specifically, this approach takes the structured HPO items \(\hat\mathcalH\) as input and returns the top-5 potential rare disease candidates under Prompt 13.

Genotype analyser

Similar to the phenotype analyser, the genotype analyser is tasked with performing professional genotype analysis by calling existing tools.

For patient genomic variant files (aligned to the GRCh37 reference genome), we initially subjected the HPO phenotype terms \(\mathcalH\) and corresponding VCF files \(\mathcalG\) to comprehensive annotation and prioritization analysis using the Exomiser46 framework, with configuration parameters detailed in Supplementary Information section 1.10, which is configured to integrate several data sources and analytical steps: population frequency filtering using databases including gnomAD54, 1000 Genomes Project55, TOPMed56, UK10K57 and Exome Sequencing Project58 across diverse populations; pathogenicity assessment through PolyPhen-259, SIFT60 and MutationTaster61 prediction algorithms; variant effect filtering to retain coding and splice-site variants while excluding intergenic and regulatory variants; inheritance mode analysis supporting autosomal dominant/recessive, X-linked and mitochondrial patterns; and gene-disease association prioritization through OMIM50 and HiPhive46 algorithms that leverage cross-species phenotype data.

The Exomiser output is ranked according to the composite exomiser_score, from which we selected the top-n candidate genes while preserving essential metadata including OMIM identifiers, phenotype score, variant score, statistical significance (P value), detailed variant info, ACMG pathogenicity classifications, ClinVar annotations and associated disease phenotypes. The curated genomic annotations were subsequently transmitted to the Central Host for downstream processing and integration.

All outputs from the specialized tools are then transformed into free texts by the agent server that can be seamlessly combined with the LLM-based central host or other LLM-driven tools. This is achieved by using a predefined templates tailored to each tool’s specific output format, such as ‘[Tool Name] identified [Disease]’ (with confidence scores included when available) for disease predictions.

External data sources

External data sources form the third tier of our DeepRare framework, providing a comprehensive external environment for tool interaction. These diverse, rare disease-related information sources support the system with professional medical knowledge; specifically, we consider medical-focused databases.

Medical literature

Scientific publications are essential for evidence-based diagnosis, especially for rapidly evolving rare diseases. DeepRare accesses peer-reviewed literature through:

-

PubMed database48 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/): the world largest database of biomedical literature containing more than 34 million papers.

-

Google Scholar (https://scholar.google.com): a broad academic search engine covering publications across diverse sources.

-

Crossref (https://www.crossref.org): comprehensive metadata database that enables seamless access to scholarly publications and related fields through persistent identifiers and open APIs.

Rare disease knowledge sources

Curated repositories that aggregate structured information about rare diseases include:

-

Orphanet49: comprehensive information for more than 6,000 rare diseases, including descriptions, genetics, epidemiology, diagnostics, treatments and so on.

-

OMIM50: a catalogue of human genes and genetic disorders, documenting more than 17,000 genes and their associated phenotypes.

-

HPO62: a standardized vocabulary of phenotypic abnormalities in human diseases, containing more than 18,000 terms and more than 156,000 hereditary disease annotations.

General knowledge sources

Broad clinical resources that provide contextual understanding include:

-

MedlinePlus (https://medlineplus.gov): a United States National Library of Medicine resource providing reliable, up-to-date health information for patients and clinicians.

-

Wikipedia (https://www.wikipedia.org): general encyclopaedia entries on all general knowledge, including medical conditions and rare diseases.

-

Online websites: resources accessible through search engines that provide up-to-date information, including medical news portals, patient advocacy groups, research institution websites and clinical trial registries that may contain the latest developments not yet published in scholarly literature.

Case collection

A large-scale case repository is constructed from several data sources to serve as the database for the case search agent server, with a subset of the data reserved as a test set to validate model performance. Specifically, the rare disease case bank comprises 67,795 cases from published literature (49,685), public datasets (13,265) and de-identified proprietary cases (4,845). To ensure fair evaluation, we implement rigorous de-duplication, excluding any identical matches between query cases and the case bank.

-

RareBench11 is a benchmark designed to evaluate LLM capabilities systematically across four critical dimensions in rare disease analysis. We use Task 4 (Differential Diagnosis among Universal Rare Diseases), specifically its public subset comprising 1,114 patient cases collected from four open datasets: MME, HMS, LIRICAL and RAMEDIS. MME and LIRICAL cases are extracted from published literature and verified manually. HMS contains data from the outpatient clinic at Hannover Medical School in Germany. RAMEDIS comprises rare disease cases submitted autonomously by researchers.

-

Mygene2 (https://mygene2.org), a data-sharing platform connecting families with rare genetic conditions, clinicians and researchers, provided additional data. We use pre-processed data (146 patients spanning 55 MONDO diseases)42, which extracted phenotype-genotype information as of May 2022, limited to patients with confirmed OMIM disease identifiers and single candidate genes to ensure diagnostic accuracy.

-

DDD63 data were obtained from the Gene2Phenotype (G2P) project, which curates gene-disease associations for clinical interpretation. We downloaded phenotype terms and associated gene sets from the G2P database11 in May 2025. After pre-processing to remove cases with missing diagnostic results or phenotypes, the final DDD cohort comprised 2,283 cases.

-

MIMIC-IV-Note44 contains 331,794 de-identified discharge summaries from 145,915 patients admitted to Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts. Since our focus is exclusively on rare diseases, we first determined whether the case involved a rare disease by prompting GPT-4o with the ICD-10 (https://icd.who.int/browse10/2019/en) codes associated with each note. Confirmed cases were mapped to our rare disease knowledge base using a methodology similar to disease normalization, whereas unmapped cases were discarded, resulting in a final dataset of 9,185 records.

-

Xinhua Hospital Dataset (in-house) encompasses all rare disease diagnostic records from 2014 to 2025, totalling 352,425 entries. Using a procedure similar to our MIMIC processing workflow, we applied GPT-4o and vector matching to eliminate records without definitive diagnoses or significant data gaps. We also consolidated several consultations for the same patient, resulting in a curated dataset of 5,820 records.

-

PMC-Patients64 comprises 167,000 patient summaries extracted from case reports in PubMed48. The RareArena GitHub65 repository has processed this dataset with GPT-4o for rare disease screening. We therefore used their pre-processed dataset, which contains 69,759 relevant records.

Genetic variant databases

Specialized repositories that support the analysis of genetic findings in rare disease diagnosis include:

-

ClinVar66: a freely accessible database containing 1.7 million interpretations of clinical significance for genetic variants, with particular value for identifying pathogenic mutations in rare disorders.

-

gnomAD (Genome Aggregation Database)54: a resource of population frequency data for genetic variants from more than 140,000 people, essential for distinguishing rare pathogenic variants from benign population polymorphisms.

-

1000 Genomes Project55: a database of human genetic variation across diverse populations worldwide.

-

Exome Aggregation Consortium67: a database of exome sequence data from more than 60,000 people.

-

UK10K57: a British genomics project providing population-specific variant frequencies for the UK population through whole-genome sequencing and WES of approximately 10,000 people.

-

Exome Sequencing Project (National Heart Lung and Blood Institute Exome Sequencing Project)58: a project focused on exome sequencing of people with heart, lung and blood disorders, providing population frequency data stratified by ancestry.

Clinical evaluation dataset curation

In this section, we introduce the curation procedure of the two proposed evaluation datasets from the clinical centres, that is, the MIMIC-IV-Rare and Xinhua Hospital datasets.

The MIMIC-IV-Note dataset comprised 331,794 de-identified discharge summaries from 145,915 patients sourced from public repositories, whereas the Xinhua Hospital dataset contained 352,425 outpatient and emergency records from 42,248 patients specializing in genetic diseases, which are in-house clinical data.

As shown in Extended Data Fig. 2, a systematic data pre-processing pipeline was implemented to ensure data quality and relevance. For the MIMIC-IV-Note dataset, we applied a two-stage exclusion process: first, cases without rare disease diagnoses were filtered out (n = 318,976 excluded), where rare disease classification was determined using an LLM under prompt 14. Subsequently, records with incomplete patient information were removed (n = 3,633 excluded), with information completeness defined as the ability to correctly extract HPO entities that could be matched successfully to the HPO database. This filtering process resulted in 9,185 cases. Similarly, the Xinhua Hospital dataset underwent parallel filtering using identical criteria, excluding 28,150 cases without rare disease diagnoses and 8,278 cases with incomplete information, yielding 5,820 cases.

Subsequently, a time-based allocation strategy was used to partition the data into evaluation and reference sets. Recent cases were designated for testing purposes, whereas historical cases were allocated to similar case libraries for retrieval-based analysis. This allocation resulted in the MIMIC-IV Test Set (n = 1,875 cases) and MIMIC-IV Similar Case Library (n = 7,310 cases), alongside the Xinhua Test Set (n = 975 cases) and Xinhua Similar Case Library (n = 4,845 cases).

It should be noted that these datasets, derived from authentic clinical records, inherently contain heterogeneous and potentially noisy phenotypic information, including patient-reported symptoms, post-operative complications, several consultation entries and incomplete documentation. This real-world complexity increases the diagnostic challenge significantly compared with curated datasets, thereby providing a more rigorous evaluation framework for clinical decision support systems in rare disease diagnosis.

Evaluation datasets statistics

As shown by Extended Data Table 1 from a statistical perspective, the number of rare diseases represented across various datasets ranged from 17 to 2,150, whereas the average number of HPO items per patient varies between 4.0 and 19.4. Moreover, following refs. 11,68, we calculated the average information content for each dataset. Information content quantifies the specificity of a concept within an ontology by measuring its inverse frequency of occurrence, that is, concepts that appear less frequently in the corpus have higher information content values. Lower information content values typically correspond to more general terms within the ontology hierarchy68. This collection thus represents a comprehensive benchmark for rare-disease diagnosis, covering 2,919 diseases from different case sources and several independent clinical centres.

Baselines

In this section we introduce the compared baselines in detail, covering specialized diagnostic methods, latest LLMs and other agentic systems.

Specialized diagnostic methods:

-

PhenoBrain28: takes free-text or structured HPO items as input and suggests top potential rare diseases by an ensembling method integrating the result of a graph-based Bayesian method (proximal policy optimization) and two machine learning methods (complement naive Bayes and multilayer perceptron) through its API.

-

PubcaseFinder29: a website that can extract free-text input first and analyse HPO items by matching similar cases from PubMed reports, returning top potential rare disease suggestions with confidence scores, accessible through its API.

Latest LLMs:

-

GPT-4o69: a closed-source model (version identifier: gpt-4o-2024-11-20) developed by OpenAI. The model was released in May 2024.

-

DeepSeek-V327: an open-source model (version identifier: deepseek-ai/DeepSeek-V3) with 671 billion parameters. It was trained on 14.8 trillion tokens and released in December 2024.

-

Gemini-2.0-flash70: a closed-source model (version identifier: gemini-2.0-flash) developed by Google. This model was released in December 2024.

-

Claude-3.7-Sonnet33: a closed-source model (version identifier: claude-3-7-sonnet) developed by Anthropic. It features a unique ‘hybrid reasoning’ mechanism that allows it to switch between fast responses and extended thinking for complex tasks. This model was released in February 2025.

-

OpenAI-o3-mini34: a closed-source model (version identifier: o3-mini-2025-01-31). This model was officially released in January 2025.

-

DeepSeek-R131: an open-source LLM (version identifier: deepseek-ai/DeepSeek-R1) with 671 billion parameters. The model was publicly released in January 2025.

-

Gemini-2.0-FT32: a closed-source model (version identifier: gemini-2.0-flash-thinking-exp-01-21). Its training data encompasses information up to June 2024, and it was released in January 2025.

-

Claude-3.7-Sonnet-thinking33: this is an extended version of Claude-3.7-sonnet that provides transparency into its step-by-step thought process. It is a closed-source reasoning model (version identifier: claude-3-7-sonnet-20250219-thinking), publicly released in January 2025.

-

Baichuan-M135: an open-source domain-specific model (version identifier: baichuan-inc/Baichuan-M1-14B-Instruct) designed specifically for medical applications, distinguishing it from the general-purpose LLMs above. This model comprises 14 billion parameters and was released in January 2025.

-

MMedS-Llama 336: an open-source domain-specific model (version identifier: Henrychur/MMedS-Llama-3-8B) specialized for the medical domain and released in January 2025. Built upon the Llama-3 architecture with extensive medical domain adaptation, this model comprises 8 billion parameters.

Other agentic systems:

-

MDAgents37: a multi-agent architecture that adaptively orchestrates single or collaborative LLM configurations for medical decision-making through a five-phase methodology: Complexity Checking, Expert Recruitment, Initial Assessment, Collaborative Discussion, and Review and Final Decision.

-

DeepSeek-V3-Search27: an LLM agent framework augmented with internet search through Volcano Engine’s platform and Web browser plugin.

Genetic analysis tools:

-

Exomiser: a variant prioritization tool (version identifier: 14.1.0 2024-11-14) that combines genomic variant data with HPO phenotype terms to identify disease-causing variants in rare genetic diseases. It integrates population frequency, pathogenicity prediction and phenotype-gene associations to rank candidate variants.

Web application

To facilitate adoption by rare disease clinicians and patients, we developed a user-friendly Web application interface for DeepRare. The platform enables users to input patient demographics, family history and clinical presentations to obtain diagnostic predictions. The backend architecture processes and structures the model outputs, presenting results through an intuitive and interactive interface optimized for clinical workflow integration. As presented in Extended Data Fig. 3, the diagnostic workflow encompasses five sequential phases:

-

(1)

Clinical data entry: users input essential patient information, including age, sex, family history and primary clinical manifestations. The platform supports the upload of supplementary materials such as case reports, diagnostic imaging, laboratory results or raw genomic VCF files when available.

-

(2)

Systematic clinical enquiry: the system first conducts ‘detailed symptom enquiry’, further investigating information that helps clarify the scope of organ involvement, family genetic history and symptom progression to narrow the diagnostic range. Users may also choose to skip this step and proceed directly to diagnosis.

-

(3)

HPO phenotype mapping: the platform automatically maps clinical inputs to standardized HPO terms, with manual curation capabilities allowing clinicians to refine, supplement or remove assigned phenotypic descriptors.

-

(4)

Diagnostic analysis and output: at this stage, the system executes a comprehensive analysis by invoking various tools and consulting medical literature and case databases to provide diagnostic recommendations and treatment suggestions for physicians. The Web frontend renders the output results for user-friendly presentation.

-

(5)

Clinical report downloading: upon completion of the diagnostic analysis, users can generate comprehensive diagnostic reports that are automatically formatted and exported as PDF or Word documents for integration into electronic health records or clinical documentation.

Detailed descriptions of the Web engineering implementations are provided in Supplementary Information section 1.4.

Ethical approval and informed consent

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Xinhua Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (Approval nos. XHEC-D-2025-094 and XHEC-D-2025-165). The study adheres to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all probands or their legal guardians (for those under 8 years old) before the initiation of genetic testing at Xinhua Hospital and Hunan Children’s Hospital. The consent forms, approved by the respective Institutional Review Boards, explicitly authorized the clinical testing as well as the subsequent use of de-identified biological samples, clinical phenotypes and genomic data for scientific research and academic publication. All data were fully de-identified and anonymized before being accessed for this study to ensure patient privacy.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.