Europe and China do not need to compete on the development of defossilization technologies.Credit: Florian Gaertner/Photothek/Getty

Last month, we described some of the nascent steps a number of European countries are taking towards defossilization — that is, to find sustainable sources of carbon (Nature 649, 267; 2026). Under net-zero emissions scenarios, carbon-based compounds will still be needed for the manufacture of everyday consumer products, including detergents, medicines and plastics. However, they cannot continue to come from fossil sources such as coal, natural gas and oil.

Defossilize our chemical world

Companies can make carbon-based molecules without exploiting fossil hydrocarbons by reacting carbon dioxide with hydrogen. The CO2 can be captured from existing fossil-based energy production or directly from the air, and hydrogen atoms can be extracted from water molecules, separating them from the oxygen atoms using a source of renewable energy. However, these chemical reactions are difficult to achieve, because both water and CO2 are highly stable molecules. This is one of the reasons why rising concentrations of CO2 in the atmosphere are such a problem.

Many European nations have active defossilization research programmes, but scaling up the technology is not a high priority for their governments. By contrast, China is forging ahead with such projects. Although opportunities to collaborate continue to shrink (see Nature https://doi.org/qrx4; 2026), defossilization is not an area in which Europe and China need to compete. Both the European Union and China are committed to reducing emissions, albeit on different timescales. Defossilization is key to these ambitions.

Bring me sunshine

China’s researchers use different terms for their defossilization programmes. ‘Green carbon science’, for example, denotes sustainable carbon-based technologies (Z. Xie et al. Natl Sci. Rev. 10, nwad225; 2023). Another term, ‘liquid sunshine’, means making carbon-based chemicals, such as methanol, using solar energy. Methanol is a common feedstock for olefins, a class of petrochemicals (such as ethylene and propylene) that are used as fuels for applications that are difficult to decarbonize, and can also be used in the manufacture of plastics, rubber and adhesives.

This September, the China Coal Ordos Energy Chemical Company’s Liquid Sunshine project, located in Inner Mongolia, is due to start producing methanol. It is one of the world’s largest such projects, and aims to produce around 100,000 tonnes of methanol per year. The estimated saving in CO2 emissions would be about 500,000 tonnes per year — admittedly only a fraction of the 12.6 billion tonnes that China emitted in 2024.

China launches world’s largest carbon market: but is it ambitious enough?

The Liquid Sunshine project will not be the largest such project globally, however — it will take joint second place alongside another Chinese initiative, based in Jiangsu. These come in close behind the biggest facility, located in Anyang, also in China; this produces 110,000 tonnes of methanol from CO2 per year.

The technologies currently being rolled out are based on advances in known chemistry. The underlying science behind the Liquid Sunshine project originated at the Dalian Institute for Chemical Physics in China. It focuses on two established chemical processes — the electrolysis of water and the hydrogenation of CO2 (J. Wang et al. Sci. Adv. 3, e1701290; 2017). Clever use of catalysts reduces the amount of energy needed at each stage of the process and brings production costs closer to those of methanol made from oil, natural gas or coal. The Anyang and Jiangsu projects differ slightly from Liquid Sunshine in their chemical approaches, adopting catalysts with roots that go back to US research from the 1980s. Together, these are arguably the world’s most advanced defossilization projects.

Importantly, China has also achieved scale. The government has compelled development through regulation, essentially mandating that key industrial sectors start to defossilize by 2027. Companies have achieved it by involving large interdisciplinary teams, spanning research chemists developing innovative catalysts and engineers scaling up processes. Analysts, policymakers and entrepreneurs have all been involved in helping to limit environmental harm and get the technologies across the ‘valley of death’ — the gap that often exists between a technology’s proof-of-concept stage and its application at scale.

Europe is not far behind. Last May, a commercial-scale CO2-to-methanol plant opened in Kassø, southern Denmark, with an annual production capacity of 42,000 tonnes. Others are in the works. For European governments, the challenge lies in continuing to prioritize green-energy production at a time when money is tight. Some now regard the concept as dispensable, particularly in the face of pressure from the US administration, which opposes both climate research and renewable energy. Putting off the transition to renewable energy will only delay what needs to be done and might make it even more expensive.

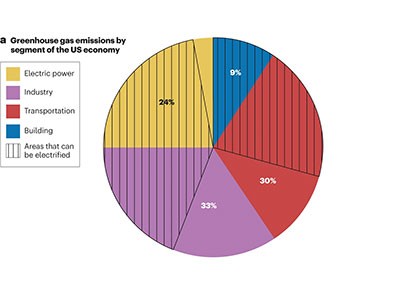

A US perspective on closing the carbon cycle to defossilize difficult-to-electrify segments of our economy

Coal is also playing a part in China’s plan to move away from oil — but there’s a twist. Not far from the Liquid Sunshine plant is a newly completed 48-billion-yuan (US$6.9-billion) facility that can convert coal first to methanol, and then to olefins. The nearby Liquid Sunshine plant could potentially turn all of the CO2 emitted by this coal-to-olefins plant to methanol, ultimately producing yet more olefins.

China and Europe have both recognized the necessity of defossilization. If the world is to minimize climate change and secure all our collective futures, it makes sense for them to work together to maximize results.