Sondra Williams is no stranger to medical diagnoses and treatments. As a teenager and young adult, she spent a decade in and out of mental-health facilities, medicated for conditions including schizophrenia and social anxiety.

‘I am not a broken version of normal’ — autistic people argue for a stronger voice in research

It wasn’t until she was in her late 30s that she finally received a diagnosis that made sense.

By then, she had married and had four children. After two of her kids were diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), doctors reviewed her medical history. Williams, too, met the criteria for the neurodevelopmental condition.

“When I finally got the diagnosis, it felt like being in labour as a mom, being in labour for most of my life and finally delivering that baby, that relief,” says Williams, who lives in Dublin, Ohio. “It was a relief to me knowing that my differences had a meaning to it. And it wasn’t me being crazy or mentally ill. It had a rhyme and reason to it.”

The diagnosis answered some questions — but raised others. Williams, now 63, has recently been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure, conditions that some studies have suggested are more common among autistic people than in the general population. “I’m terrified of my future because I’m plagued with so many health issues,” says Williams.

The number of older autistic people is surging. A study analysing data from more than 200 countries, published online last year1, reported that the number of autistic people aged 70 or older rose from 894,700 in 1990 to nearly 2.5 million in 2021. This figure is estimated to double to 5.1 million people by 2040, according to the study.

Some of the increase is simply because the world’s population is growing. But awareness of and screening for autism have also improved. Another important factor is a change in the diagnostic criteria that was made about a decade ago: before this, autism was predominantly diagnosed in early childhood; the revision meant that adults could be given the diagnosis.

And yet, researchers know almost nothing about how autism might affect people as they age. Only 0.4% of studies of autism since 2012 included autistic people in midlife or old age2.

The fact that Williams and other autistic adults live with such uncertainty concerning their health stems from two blind spots in scientific research. Firstly, the study of autism has historically focused on children and adolescents. Secondly, studies on ageing, which have ramped up in recent years, often exclude autistic people.

Features of autism can affect age of diagnosis — and so can genes

But what researchers do know paints a picture of a group that might be more susceptible to certain health conditions, such as Parkinson’s disease and heart disease, and more-severe symptoms of menopause. Autistic people might benefit from extra support as they age — making it imperative to include them in research.

“People want research where there’s going to be a tangible impact on their lives. With the research area of autism and ageing, we’re still at that point of setting the scene,” says Gavin Stewart, a developmental psychologist at King’s College London, UK.

Lost generation

Autism was first identified as a distinct condition by two researchers in the 1940s3,4. Before that, it was thought to be part of schizophrenia. Even in the 1960s, when autism was added to diagnostic manuals, it was listed as a schizophrenia-related condition that occurred in children. It was not until 1980 that autism became recognized as a stand-alone condition in such manuals.

The criteria for characterizing it continued to change. The official diagnosis of ASD — including how to identify it in adults — was introduced only in 2013. As a result, there are generations of autistic people who grew up not knowing that they were autistic, nor getting the support they needed to thrive, because they were excluded by earlier diagnostic criteria.

The largest survey to estimate the prevalence of autism in adults in England suggested that up to 75% of autistic people aged 20–49 and more than 90% of those over 50 are undiagnosed5.

This means that millions of people around the world might not be receiving the support that they need. It also makes it difficult for researchers to recruit older participants into studies and to follow them over the long term.

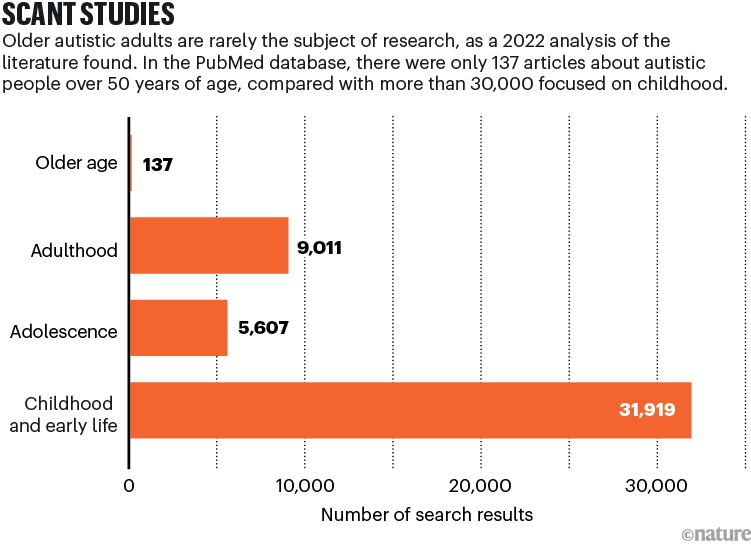

Between 1980 and 2021, more than 40,200 papers on autism in childhood and adolescence were published, compared with only 174 papers on autism during old age2 (see ‘Scant studies’).

Source: Ref. 2

“We know almost nothing,” says Gregory Wallace, a developmental neuropsychologist at the George Washington University in Washington DC.

But there has been a growing interest in ageing and autism, and studies on older autistic adults have nearly quadrupled2 since 2012.

Health risks

Some of these studies have asked whether autistic adults will face any particular health risks as they age. The data so far suggest that they might.

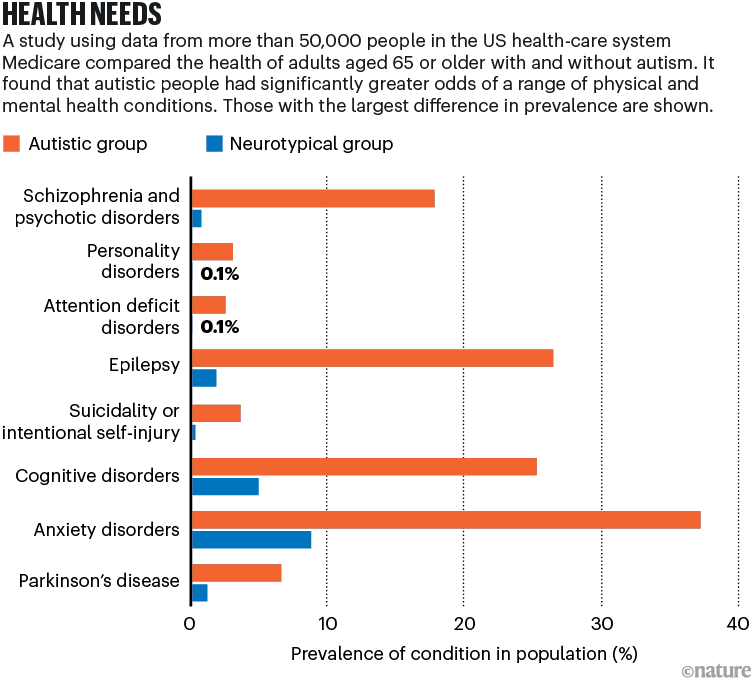

An analysis of health records from nearly 5,000 autistic adults and 46,850 neurotypical adults over 65 years old found that the autistic group had higher rates of mood disorder, epilepsy and gastrointestinal disorders. Autistic adults, nearly 44% of whom had an intellectual disability, were also more likely to have a diagnosis of age-related conditions, such as osteoporosis, heart disease, Parkinson’s disease and dementia6 (see ‘Health needs’).

Source: Ref. 6

In a larger survey of around 250,000 autistic people, people with intellectual disabilities or both, presented at a conference in 2024 and not yet published, Wallace and his colleagues reported that the risk of developing symptoms associated with Parkinson’s disease was three times higher in that group than in the general population (see go.nature.com/4rcft9w). Previous genetic studies have also found that autism is linked to mutations in PARK2, a gene associated with Parkinson’s disease7.

But interpreting these findings is complicated. Many autistic people have challenges with movement or differences across development compared with neurotypical people, says Wallace. And it is difficult to determine whether the Parkinson’s-like symptoms occur as an ageing-related complication or whether their roots were there all along.

Neuroscientist Zheng Wang at the University of Florida in Gainesville is investigating movement difficulties in autistic people aged 40 to 60 years using brain imaging. In her project, which ends next year, she wants to find out whether structural changes in the cerebellum and basal ganglia — brain areas involved in coordinating movement — might underlie any motor difficulties.

Ageing autistic adults are also “more likely to have been prescribed various psychotropic medications” in their earlier life than are neurotypical people of the same age, says Wallace. Long-term use of such drugs, including antipsychotics and anti-seizure medications, can lead to a cascade of side effects, including Parkinson’s-like symptoms, that might not manifest until later life.

That said, when Wallace and his team did another analysis excluding those who had taken such drugs during the study window, the likelihood of Parkinson’s-like symptoms was still higher than in the general population.

Researchers have reported similar patterns for other neurodegenerative conditions, such as Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. The largest study of its kind, published last year, examined data from 90 million health-care records, which included 114,582 autistic individuals. The authors revealed that up to 35% of autistic adults aged over 64 had a diagnosis of dementia, compared with only 10% in the general population8.

But studies based on medical records might be including only a subset of autistic adults who have interacted with health systems or at least have a diagnosis.

Inside the ageing autistic brain

Some research on autistic adults paints a more positive picture of health in later life. For instance, brain-imaging studies have found that some neuronal networks showed less age-related change in autistic adults than in neurotypical ones. “If there was a difference at the beginning of life, there was also a difference later on in life. But this gap between people who were autistic and non-autistic didn’t grow bigger with increasing age,” explains Hilde Geurts, a neuropsychologist at the University of Amsterdam who found such a difference in a 2020 study9. She and her team were surprised that the gap didn’t widen with age — that autistic people didn’t seem to be subject to accelerated ageing.

But she acknowledges that not all such studies agree. “It is not what everyone finds across different labs,” says Geurts.

Nonetheless, the work of Geurts and others has led to the suggestion that autism could protect against some of the declines in cognitive abilities that occur with age. “Older autistic folks have these really incredible compensatory mechanisms,” says Blair Braden, a behavioural neuroscientist at Arizona State University in Tempe.

Neuroscientists Blair Braden (right) and Cory Riecken at Arizona State University in Tempe used brain scans to study age-related changes in autistic adults.Credit: Arizona State University

She and her colleagues wanted to document age-related changes in the brain in autism, so they imaged the brains of 25 autistic adults and 25 neurotypical adults aged 40 to 70 years old for up to 5 years10. They focused on tasks of short- and long-term visual memory. When they looked at the data from the autistic group, they found that “there is a subset of people that are actually experiencing accelerated memory decline” compared with neurotypical participants, “and some people who are staying stable,” says Braden — much like Geurts found.