Credit: Olga Yastremska/Alamy

Calling nanoscientists: your field needs you to try to replicate a landmark finding that quantum dots can act as biosensors inside living cells. As part of the first large-scale effort in the physical sciences to tackle the reproducibility crisis, researchers in France and the Netherlands are offering funds and resources in exchange for a few months of work.

“We are trying to use replication as a tool to solve a controversy or, you know, to get closer to the truth,” says Raphaël Lévy, a physicist at Sorbonne Paris North University, who co-leads a European project called NanoBubbles, which focuses on self-correction in science. The project — named after bubbles of misinformation that can form when bad science is left uncorrected — made its call for help on 11 February. The appeal comes as separate research groups in psychology and the social sciences prepare to offer updates on their own large-scale replication efforts — prompted by the large number of scientific results that can’t be repeated when others run the same tests.

Sometimes, these trials check that the data reported in published papers justify the results and conclusions. In other cases, they repeat the experiments from scratch. Last year, for example, a large-scale reproducibility project in Brazil tried and failed to validate dozens of biomedical studies.

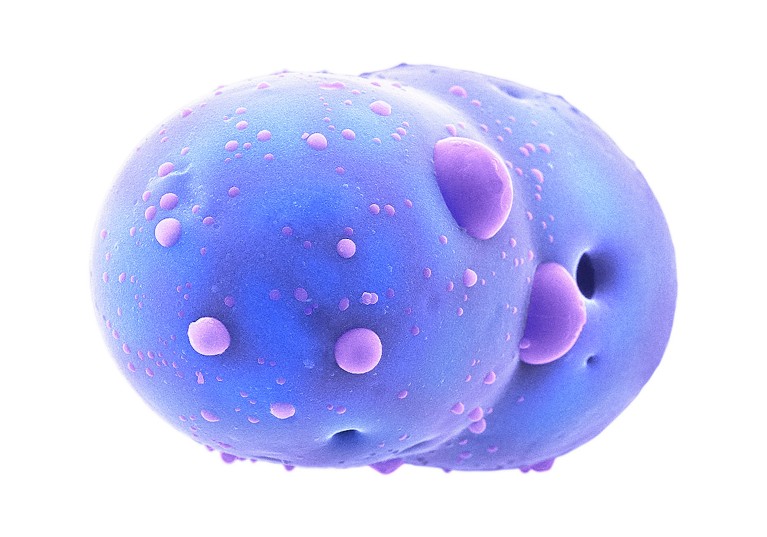

Engineered nanoparticles such as these can be used to deliver drugs into the body.Credit: David McCarthy/SPL

Lévy, one of four researchers who lead the NanoBubbles project, which is backed by an €8-million (US$9.5-million) grant from the European Research Council, wants laboratories to revisit a 2012 study that suggested tiny, fluorescent carbon nanoparticles can detect copper ions inside living cells. This could have medical relevance because high copper levels are linked to diseases such as cancer and neurodegenerative disorders. The paper1, authored by a team led by Yang Tian, a chemist at Tongji University in Shanghai, China, is part of a wider research effort to develop engineered nanoparticles for various applications in imaging, diagnostics and drug delivery.

After pre-registering what they intended to do, the NanoBubbles team has tried and failed to replicate the findings in the paper. “I was really surprised, because in the published protocol, the fluorescence of the particles decreased when the concentration of the target increased, but in our experiments, it just stayed the same,” says Mustafa El Gharib, a nanoscientist also at Sorbonne Paris North University who attempted the replication. Tian did not respond to enquiries from Nature.

1,500 scientists lift the lid on reproducibility

Field variations

There are many possible reasons why work in this field might not replicate, says Wolfgang Parak, a physicist at the University of Hamburg, Germany, who is a member of the NanoBubbles advisory board but was not involved in Gharib’s experiments.

As an example, Parak notes that one of his synthesis reactions became hard to reproduce after he moved his lab from the United States to Europe. “Surface chemistry is extremely sensitive to small impurities,” he says, and reagents in different countries could have varying amounts of contamination. Another problem is that experimental protocols sometimes don’t describe steps in sufficient detail. So, any study that identifies crucial points in protocols and how to improve them is helpful.

Parak thinks the NanoBubbles replication was done well. “They really measured everything very carefully and used state-of-the-art techniques,” he says. Levy’s team described the results in a preprint posted last year2, which is due to be published in Royal Society Open Science.

‘Publish or perish’ culture blamed for reproducibility crisis