AI slop is flooding computer science journals and conferences.Credit: Quality Stock/Alamy

Fifty-four seconds. That’s how long it took Raphael Wimmer to write up an experiment that he did not actually perform, using a new artificial-intelligence tool called Prism, released by OpenAI last month. “Writing a paper has never been easier. Clogging the scientific publishing pipeline has never been easier,” wrote Wimmer, a researcher in human–computer action at the University of Regensburg in Germany, on Bluesky.

Large language models (LLMs) can suggest hypotheses, write code and draft papers, and AI agents are automating parts of the research process. Although this can accelerate science, it also makes it easy to create fake or low-quality papers, known as AI slop.

Computer science was a growing field before the advent of LLMs, but it now at breaking point. The 2026 International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML) ihas received more than 24,000 submissions — more than double that of the 2025 meeting. One reason for the boom is that LLM adoption has increased researcher productivity, by as much as 89.3%, according to research published in Science in December1.

“It’s a volume far beyond what the current review system was designed to handle,” and makes “thorough and careful evaluation increasingly infeasible”, says Seulki Lee, a computer scientist at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology in Daejeon , South Korea.

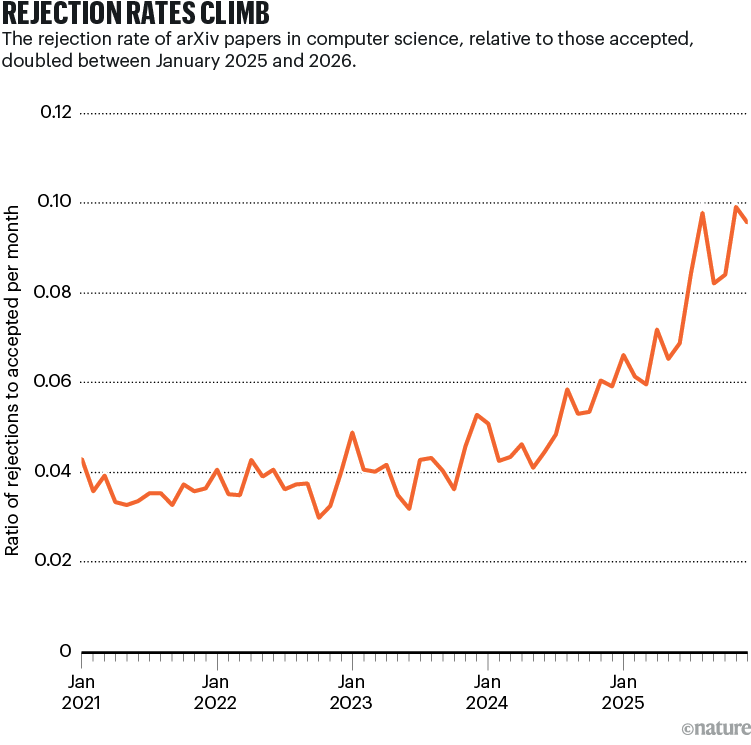

Volume is not the only problem. Many authors fail to properly validate or verify AI-generated contents, says Lee. Analyses of submissions to prominent AI conferences show that some papers are entirely AI-generated and dozens contain AI fabrications, known as hallucinations. Since the advent of ChatGPT in November 2022, the number of monthly submissions to the arXiv preprint repository has risen by more than 50% and the number of articles rejected each month has risen fivefold to more than 2,400 (see ‘Rejection rates climb’).

One response is to fight fire with fire by using AI in peer review or to weed out fake papers. Other options are blunter. The arXiv has, for example, added eligibility checks for first-time submitters and banned computer-science review articles that have not been previously accepted by a peer-reviewed outlet. The organizers of the International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI), meanwhile, have sought to limit submissions by introducing a policy that requires researchers to pay US$100 for every subsequent paper after their first. These payments then get distributed among reviewers.

The stakes are high, says Lee. If the issue is not addressed, “trust in scientific research, particularly within computer science, faces a substantial risk of erosion,” he says.

AI slop

AI slop is hard to spot by conventional means, says Paul Ginsparg, a physicist at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, and a co-founder of the arXiv. Volunteer moderators can no longer use how well a paper engages with the relevant literature and methods to gauge its merit. “AI slop frequently can’t be discriminated just by looking at abstract, or even by just skimming full text,” he says. This makes it an “existential threat” to the system, he says.

So far, conferences have coped mainly by boosting the reviewer pool. Last year, the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) introduced a requirement for anyone submitting a paper to also peer review others’ submissions. The organizers of the high-profile NeurIPS conference acknowledged that their recruitment drive meant they would probably be using more junior reviewers. Several conferences also already incentivize high-quality reviewing by offering the best reviewers benefits such as waived conference-registration fees, says Lee.

Major AI conference flooded with peer reviews written fully by AI

Several are introducing new measures next year to deter slop. ICML organizers have introduced a policy to stop authors submitting multiple similar papers by requiring them to send the reviewers copies of their other submitted articles, with violations potentially resulting in all papers by those authors being rejected.

More-radical ideas include moving away from publishing via conferences to a rolling, journal-based model. This would avoid an annual crunch of peer review, but some researchers might not want to miss the prestige and networking opportunities of conferences, says Nancy Chen, an AI researcher at the A*Star Institute for Infocomm Research in Singapore, and who served as a program chair for the high profile NeurIPS conference last year.