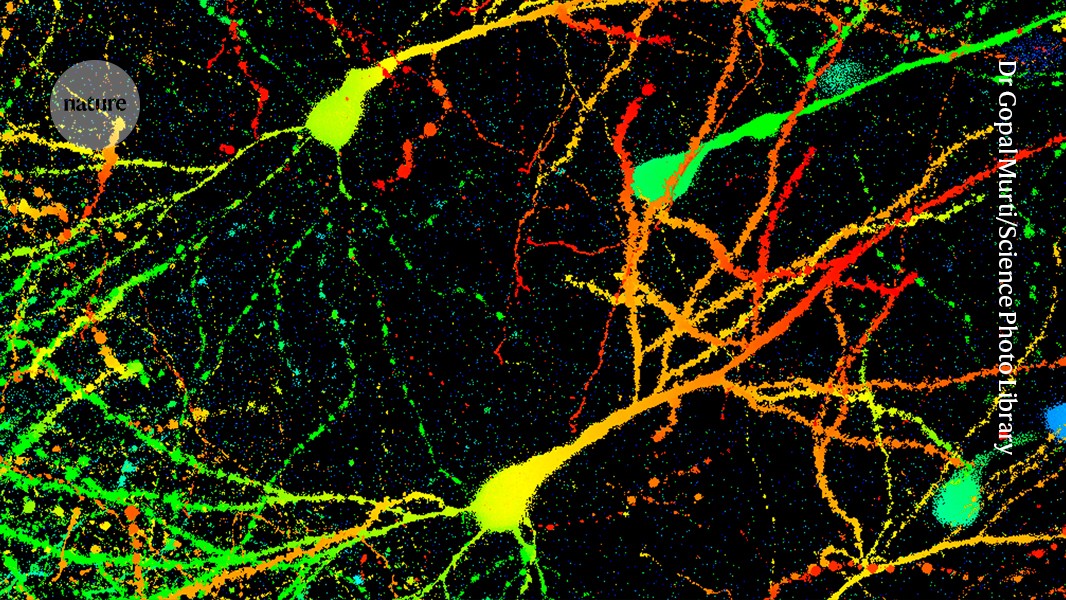

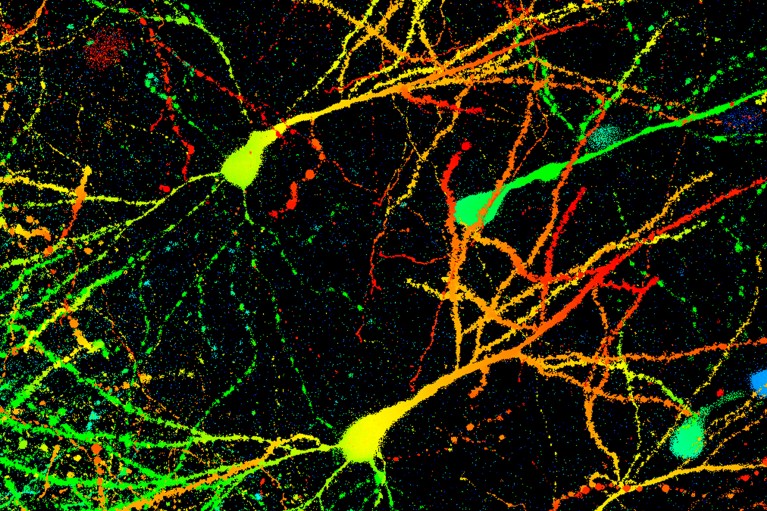

Certain neurons in mice become more easily activated after multiple exercise sessions, a study has found.Credit: Dr Gopal Murti/Science Photo Library

Exercise pumps up your muscles — but it might also be pumping up your neurons. According to a study published today in Neuron1, repeated exercise sessions on a treadmill strengthen the wiring in a mouse’s brain, making certain neurons quicker to activate. This ‘rewiring’ was essential for mice in the study to gradually improve their running endurance.

The work reveals that the brain — in mice and, presumably, in humans — is actively involved in the development of endurance, the ability to get better at a physical activity with repeated practice, says Nicholas Betley, a neuroscientist at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and a co-author of the paper.

“You go for a run, and your lungs expand, your heart gets pumping better, your muscles break down and rebuild. All this great stuff happens, and the next time, it gets easier,” Betley says. “I didn’t expect that the brain was coordinating all of that.”

Brain workout

Betley and his colleagues were curious about what happens in the brain as people get stronger through exercise.

Why is exercise good for you? Scientists are finding answers in our cells

They decided to focus on the ventromedial hypothalamus, a brain region that regulates appetite and blood sugar. The team then zeroed in on a group of neurons in that region that produce a protein called steroidogenic factor 1 (SF1), which is known to play a part in regulating metabolism2. A previous study3 found that the deletion of the gene that codes for SF1 impairs endurance in mice.

Betley’s team monitored the activity of SF1 neurons in mice running on a treadmill and found that these cells were indeed activated by exercise. Interestingly, one group of SF1 neurons became active only after exercise sessions ended. After several training sessions, the number of neurons that were activated post-run, as well as the magnitude of their activation, increased.

When the researchers examined brain slices from mice that had trained consistently over three weeks, they saw changes in the SF1 neurons’ electrical properties compared with mice that had not repeatedly exercised. These changes indicated that the neurons in the trained mice had become easier to activate. They also found that repeated exercise doubled the number of synapses — connections between the neurons — that were ‘excitatory’, or primed to fire off an electrical signal.