Experimental set-up

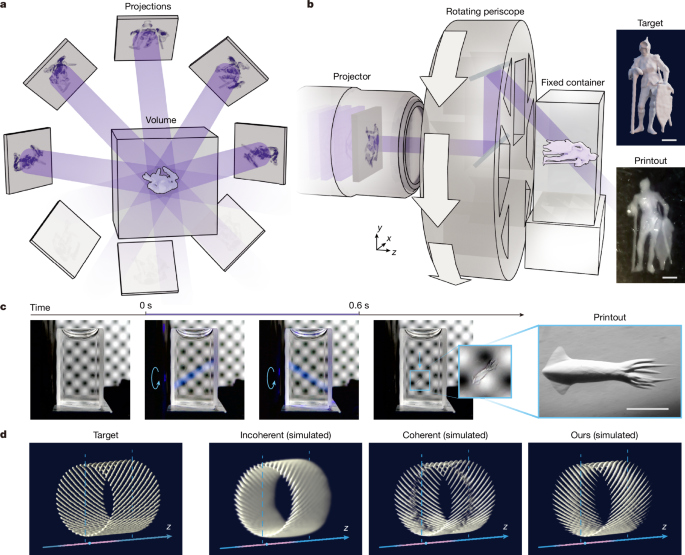

Extended Data Fig. 2 shows the experimental set-up of DISH. A coherent 405-nm light beam emitted from the continuous-wave diode laser CNI MDL-HD-405 with a linewidth of 1.5 nm is modulated by a DMD equipped with a total internal reflection prism. The DMD (TI DLP9500) driven by ViALUX V-9501 features a pixel size of 10.8 μm, an array size of 1,920 × 1,080 and a refresh rate of 17.9 kHz. The patterned beam passes through a 4f system, consisting of a tube lens (Thorlabs TTL200-A), an aperture and an objective lens with a working distance of 34 mm (Mitutoyo M Plan Apo 2×, NA 0.055). The aperture allows only the central diffraction order to pass. The beam is then directed into a periscope fixed on a hollow rotating platform, driven by an alternating current servo motor (Panasonic MSMJ042G1U). Finally, the beam is obliquely projected into a quartz cuvette, with an entry maximum power density of 150 mW cm−2 and a total maximum power of 40 mW, limited by the laser. The periscope consists of two small mirrors (Extended Data Fig. 2c,d). The first mirror is inclined at a 45° angle relative to the z-axis and the second mirror is inclined at 22.5°. After reflection within the periscope, the beam is projected into the container at a 45° angle. When the incident angle is 45°, this configuration yields a reasonable axial feature size for most materials with different refractive indices, while keeping the interface reflectivity low. This mechanical design accommodates a light beam of 6 mm in diameter. As shown in Extended Data Fig. 2e, the printing area exhibits a centrally symmetric spindle-like shape, which can be approximated by a cylinder and two cones. The total volume of this approximated shape is \(\frac14\rm\pi d^3\frac1\tan \theta _\rmr\left(\frac1\cos \theta _\rmi-\frac23\right)\), in which θi represents the incident angle, θr represents the refracted angle and d represents the beam diameter. When d = 5.832 mm (5.4 μm × 1,080) and the refractive index of the material is 1.48, the total volume is 214.1 mm3.

The time sequence diagram of the synchronization of rotation and the projection pattern is detailed in Extended Data Fig. 3. A National Instruments PCIe-6363 multifunction I/O device is used to generate voltage pulses and control various components, including the laser shutter, camera shutter, projection angle and DMD projections. The servo motor is operated at 1,000 rpm, resulting in a period of 0.6 s for the hollow rotating platform with a 1:10 reduction ratio. DMD projections are synchronized with the actual angle. During the printing process, the laser shutter is closed until the motor speed stabilizes. The shutter controls the exposure time to be 0.6 s. Typically, the servo motor is triggered with a 60-kHz square wave, whereas the DMD is triggered with a 3-kHz square wave, showing 1,800 projections per cycle. The running speed could also be adjusted as needed. Because the laser power used in our prototype system is relatively low, all trigger parameters described here are specifically configured for the 0.6-s exposure time rather than for maximum operating speed.

Modelling of the system

The relationship between the beam propagation coordinates (xr, yr, zr) and the world coordinates (x, y, z) is established to ensure compatibility with any 3D projection direction. The coordinates (x, y, z) are defined according to the container. The z-axis represents the rotation axis, the x-axis represents the horizontal direction and the y-axis represents the vertical direction. The coordinates (xr, yr, zr) are defined according to the beam inside the container, with the zr-axis indicating the propagation direction. Both coordinate systems share the same origin, which is the printing centre. In our experimental set-up, the coordinate transformation can be represented by the Euler angle representation:

$$(x,y,z)^\rmT=R_Z(\varphi )R_X(\theta _\rmr)R_Z(-\varphi )\rm\cdot (x_\rmr,y_\rmr,z_\rmr)^\rmT$$

in which φ represents the platform angle and θr represents the refraction angle in the material. RX and RZ represent the rotation around the x-axis and z-axis, respectively.

In wave optics, the propagation is modelled as:

$$\left\{\beginarrayc\mathcalH_\varphi (z_\rmr)=\mathcalF^-1H(z_\rmr+l_\rmr,\lambda _\rmr)\cdot S_\varphi \cdot H(l_\rmi,\lambda _\rmi)\mathcalF\\ H(z,\lambda )=\exp \left\\rmj\frac2\rm\pi \lambda z\sqrt1-(\lambda f_x)^2-(\lambda f_y)^2\right\\endarray.\right.$$

Here \(\mathcalF\) denotes the Fourier transformation that converts complex amplitudes into angular spectra. H(li, λi) and H(zr + lr, λr) are the propagation matrices in air and in the material, respectively. Sφ represents refraction, which is achieved through a distorted stretching in the angular spectrum. As the plane wave remains a plane wave after refraction at a flat interface, the corresponding relationship of angular spectrum coordinates before and after refraction can be calculated using the 3D form of Snell’s law. This distorted stretching on the angular spectrum is implemented by the imwarp function in MATLAB.

Adaptive-optics-based calibration

To simplify the calibration process, the optical system preceding the periscope was adjusted to ensure that the beam emitted from the DMD centre precisely coincides with the rotation axis of the platform. Therefore, the rotating light path was adjusted to be centrosymmetric and the angle of incidence θi remained unchanged. Owing to the symmetry of the system, the beam emitted from the DMD centre should generate intensity with the shape of a one-sheet hyperboloid within the container. Its symmetric centre was considered as the printing centre and the origin of the world coordinates. The distance from the printing centre to the front surface of the container was denoted as z0. During calibration, the optical devices were fixed and only the projections were updated as the platform rotated.

First, a coarse linear relationship between the DMD pixel coordinates, platform angle and 3D coordinates inside the container was established. DMD pixels were activated individually while the platform was slowly rotating and the corresponding excited fluorescence in the container 18 μg ml−1 coumarin-30 DMSO resolution was captured in real time by the front and side cameras equipped with emission filters. As illustrated in Extended Data Fig. 8b, the projection angle φ of the beam was determined using the front camera, whereas the angle of refraction θr was measured with the side camera. The remaining two degrees of freedom of the ray were calculated by the position of its intersection point with the z = 0 plane. The DMD pixel was then shifted according to the fluorescent photographs taken from the cameras. Finally, a set of DMD offset pixels that emitted beams to exactly intersect the printing centre was obtained, denoted by \((x_\rmi^0\varphi ,y_\rmi^0\varphi )\). Extended Data Fig. 8c,d show an example of the positions of the beam before and after calibration.

Subsequently, the propagation distance from the conjugate plane to the interface of the container was measured. When the platform angle φ = 0, line segments at the y–z plane (Fig. 3c) were projected and the symmetrical centre of the resulting 3D intensity was considered as the approximate conjugate plane. Several images were captured at different focal planes with an electrotunable lens and the symmetric centre of their composite photograph identified the approximate conjugate plane of the DMD. The propagation distance from the printing centre to the approximate conjugate plane was denoted as \(z_\rmr^\rmc\).

Finally, the precise calibration was operated with holographically synthesized patterns. The focusing performance throughout the container was checked and the calibrated parameters were fine-tuned until the intensities at all platform angles were consistent with the simulation of wave-optic propagation. When the container was shifted for a distance of z′ along the z-axis and the material was replaced by that with a refractive index of n′, these parameters could be recalculated as follows without the requirement of extra calibration experiments:

$$\beginarrayc\beginarraycn^\prime \sin \theta _\rmr^\prime =n\sin \theta _\rmr\\ z_^\prime \tan \theta _\rmr^\prime =z_\tan \theta _\rmr-z^\prime \tan \theta _\rmi\\ z_\rmr^\rmc^\prime \sin \theta _\rmr^\prime =z_\rmr^\rmc\sin \theta _\rmr\\ (x_\rmi^0\varphi \prime ,y_\rmi^0\varphi \prime )=(x_\rmi^0\varphi ,y_\rmi^0\varphi )\endarray\endarray$$

Holographic optimization algorithm

First, the optimization problem to obtain the coarse 3D intensity distributions \(I_\varphi ^\mathrmcoarse\) contributed by each angle is shown below:

$$\left\{\beginarrayc\min \,L=\sum _\overrightarrowx\in A\,^2+\sum _\overrightarrowx\in \tildeA\,^2\\ \rms\,.\rmt\,.\,I=\sum _\varphi I_\varphi ^\mathrmcoarse\endarray,\right.$$

in which \(\vecx\) represents the 3D coordinates in the objective area, φ represents the projection angle, \(\mu (\vecx)\) represents the attenuation during the propagation in materials and thus \(\mu (\vecx)I(\vecx)\rm\triangle t\) represents the accumulated dose at each point. A represents the 3D region of the target model to be printed, in which the accumulated dose is expected to be dh for polymerization and \(\widetildeA\) represents the area outside the target region in which the accumulated dose is supposed to be smaller than the threshold dl to avoid overexposure. Δt corresponds to the temporal duration of each projection. The number of projection angles for optimization in this step can be reduced by duplicating the pattern with adjacent angles to accelerate the computation process. The binary restrictions and the effect of diffraction are ignored in this process; therefore, the traditional methods33,34 can be implemented to solve this problem.

Then, the following holographic problem is sequentially solved for each group of G adjacent binary projection patterns:

$$\left\{\beginarrayc\min \,L=\sum _\overrightarrowx\in A\,^2+\sum _\overrightarrowx\in \tildeA\,^2\\ \rms\,.\rmt\,.\,I=\sum _\varphi \prime \notin \\varphi _g\I_\varphi \prime ^\mathrmtemp+\sum _\varphi _g\,\mathcalH_\varphi _g(\delta _\varphi _gu)^2,\,\delta _\varphi _g\in \0,1\,\,g\in \1,2,\ldots ,G\\endarray.\right.$$

Here the loss function is the same as that in the previous problem. \(I_\varphi ^\mathrmtemp\) is initialized as \(I_\varphi ^\mathrmcoarse\) and will be updated to be \(\mathcalH_\varphi (\delta _\varphi u)^2\) after δφ is holographically optimized. φg is a set of adjacent G angles centred at φ. \(\delta _\varphi _g\) is the binary image shown by the DMD for the angle φg. u represents the non-uniform amplitude distribution of the beam, which can be calibrated using a beam profiler. \(\mathcalH_\varphi _g\) represents the process of light propagation in wave optics considering the refraction at the surface of air and material.

To solve this discrete optimization in the complex number domain, a virtual complex amplitude Vφ is introduced to represent the average power of these G binary projections. It satisfies the condition that \(V_\varphi ^2\approx \sum _\varphi _g\,^2/G\). Within each iteration, the phase of \(\mathcalH_\varphi V_\varphi \) is assumed to be constant and the binarization error is temporarily ignored, that is \(^2\approx \sum _\varphi _g\,\mathcalH_\varphi _g(\delta _\varphi _gu)^2/G\), thus the gradient descent of Vφ can be approximated. Then Vφ is updated along its gradient-descent direction and converted to its nearest positive real number.

The image set \(\\delta _\varphi _g\\) is calculated by \(\delta _\varphi _g=\V_\varphi ^2\ge (g-0.5)/G\cdot u^2\\) and the best \(\\delta _\varphi _g\\) that minimizes the loss function is selected as the output. The flow chart of the holographic optimization is demonstrated in Extended Data Fig. 4a. Notably, directly converting a greyscale projection into a sequence of binary projections results in degraded intensity contrast for out-of-focus planes, because the light beams projected at different time points lack coherence to each other. Consequently, the intensity of direct projection \(^2\) differs from that of the incoherent synthesis of binary projections \(\sum _\varphi _g\,\mathcalH_\varphi _g(\delta _\varphi _gu)^2/G\), as shown in Extended Data Fig. 4b. The incoherent synthesis more accurately represents our experimental implementation, thereby reducing dose estimation errors.

In the printing experiments, a volume pixel size of 5.4 μm was used to match the DMD pixel size at the conjugate plane. In the simulations depicted in Fig. 2 and Extended Data Figs. 5 and 6, a volume pixel size of 1.8 μm was used. A total of 180 greyscale images were derived from the traditional algorithms and the binarization parameter G was set to 10, yielding 1,800 binary projections to minimize the effect of motion blur. Each group underwent 20 holographic optimization cycles. For a model with dimensions 1,350 × 1,350 × 1,852 (corresponding to 7.3 × 7.3 × 10.0 mm), our implemented holographic algorithm49, using the parameters mentioned above, required approximately 24 h to complete in MATLAB R2023a, running on an Intel Core i7-11700 CPU. Deep learning methods and GPUs may be used in the future to accelerate the computing process.

Materials used for printing

PEGDA hydrogel

20% w/v PEGDA with an average molecular weight of 1,000 g mol−1 (PEGDA 1000, P902470, Macklin) was dissolved in deionized water. 0.25% w/w of lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP; L157759, Aladdin) was added as a photoinitiator. This solution was used for Fig. 1c, Extended Data Fig. 9d and Supplementary Video 1.

PEGDA mixed solvent

20% w/v PEGDA 1000, 20% w/v deionized water and 60% polyethylene glycol with an average molecular weight of 400 g mol−1 (PEG 400, P815616, Macklin) were mixed and stirred for 30 min. 0.25% LAP was added as a photoinitiator. This gel was used for Figs. 4a–f and 5b,c, Extended Data Fig. 9a,b,e,k and Supplementary Video 2. PEGDA mixed solvent ink was used to characterize the performance of DISH. PEG can serve as porogen50 and causes polymerization-induced phase separation in the printed samples. Although the polymer frameworks are still formed by PEGDA, the samples appear white instead of transparent owing to the scattering induced by phase separation. The enhanced scattering makes the printouts more visible and the printing process can thus be directly captured by cameras. Also, binary solvents could induce faster polymerization than a single solvent51 and faster curing is suitable for DISH to increase the printing speed.

PEGDA resin

2 mM photoinitiator diphenyl (2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl) phosphine oxide (TPO; T107643, Aladdin) was added to PEGDA with an average molecular weight of 1,000 g mol−1 (P131592, Aladdin) and stirred until fully dissolved. This material was used to print objects in Figs. 1b, 4l–o and 5e–h, Extended Data Fig. 9f,g,i,j,l,m and Supplementary Videos 3 and 4.

SilMA hydrogel

SilMA was synthesized following the protocol in ref. 52. 2 g SilMA was dissolved in deionized water to make a 10-ml solution. The 20% w/v SilMA was used with 0.25% LAP and the printouts are shown in Extended Data Fig. 9o.

GelMA hydrogel

GelMA was synthesized following the protocol in ref. 53. 1 g GelMA was dissolved in deionized water to make a 10-ml solution. The 10% w/v SilMA was used with 0.25% LAP and the printouts are shown in Fig. 5k.

BPAGDA resin

BPAGDA (411167, Sigma) was mixed at 3:2 w/w with 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA; H810855, Macklin). 2 mM TPO was added and the mixture was stirred at 60 °C for 30 min. The printouts are shown in Fig. 5j.

DPHA resin

DPHA (D889657, Macklin) was mixed at 2:1 w/w with HEMA. 2 mM TPO was added and the mixture was stirred at 60 °C for 30 min. The printouts are shown in Fig. 5i and Extended Data Fig. 9n.

UDMA resin

UDMA (D885973, Macklin) was mixed at 4:1 w/w with HEMA. 2 mM TPO was added and the mixture was stirred at 40 °C for 30 min. The printouts are shown in Extended Data Fig. 9c,p.

UDMA + PEGDA resin

UDMA was mixed at 1:1 w/w with PEGDA. 2 mM TPO was added and the mixture was stirred at 40 °C for 30 min. The printouts are shown in Extended Data Fig. 9h.

The viscosity of the inks was tested by Anton Paar MCR 302e, rotor CP50, shearing rate 100 s−1. The viscosities of these materials are: 20% PEGDA hydrogel: 4.734 cP; 20% SilMA hydrogel: 40.12 cP; PEGDA mixed solvent: 63.85 cP; PEGDA resin: 99.11 cP; BPAGDA resin: 656.38 cP; DPHA resin: 750.49 cP; UDMA resin: 562.99 cP. These samples were tested at room temperature (25 °C). 10% GelMA hydrogel was used and tested at 40 °C as a liquid ink and the viscosity is 14.15 cP.

Printing and post-processing

The inks can be directly replaced for each printing process and resin reuse could be achieved through heating and exposure to ambient air, as demonstrated in previous volumetric printing systems. Furthermore, low-viscosity materials used for printing, such as PEGDA aqueous solution, facilitate the spontaneous replenishment of dissolved oxygen. Gentle pipetting between printing sessions was conducted to maintain the printing performance for these low-viscosity inks.

The printouts were gently separated from the uncured materials and washed with water or ethanol. For high-viscosity resins, heating and ultrasonics could be involved to aid cleaning. Subsequently, an extra 405-nm light exposure (30 mW cm−2) was applied for 60 s in corresponding photoinitiator solutions (water containing 0.25% LAP or ethanol containing 2 mM TPO). For hydrogel samples, dipotassium hydrogen phosphate solution (9.7% w/v) was used to balance the swelling in Fig. 4 and Extended Data Fig. 9a,b, making the microscopic length the same as the designed length.

Visualization of the printed products

In Supplementary Videos 1 and 2, the products were directly imaged within the material. In Supplementary Video 1, the subtle variation in refractive index was visualized by placing a checkerboard pattern behind the container. In Supplementary Video 2, a green laser beam was used to enhance scattering without influencing the curing reaction. In Supplementary videos 3 and 4, the cleaning process is temporarily put in a cuvette for better filming, with usual washing using bigger containers and more solvent to ensure cleanliness.

The products were post-processed and then photographed in various ways: macro photography (Figs. 1b, 4a,j,k,m and 5g–k and Extended Data Fig. 9b left, 9f,j–p), stereoscopy (Fig. 5e,f and Extended Data Fig. 9c,i) and bright-field microscopy (Figs. 1c right and 4a–f,h,i,n,o and Extended Data Fig. 9a,b,d,e,g). The hollow structure was validated by injecting different colours of ink, including Fig. 5h,k and Extended Data Fig. 9g,i,o. The X-ray computed tomography scanning in Extended Data Fig. 9h was conducted using a ZEISS Xradia 620 Versa.

All dimensions of the printed objects are reported as mean ± standard deviation. For the linewidths in Fig. 4a,b, n = 20 measurements were taken for each stripe group across the sample. Data in Fig. 4g were obtained at each indicated axial position, with n = 6 measurements per position. For the fishbone width in Fig. 4i, n = 10 measurements were performed. For the conch structure in Fig. 4m–o, a total of n = 40 measurements was conducted across its various lines.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.