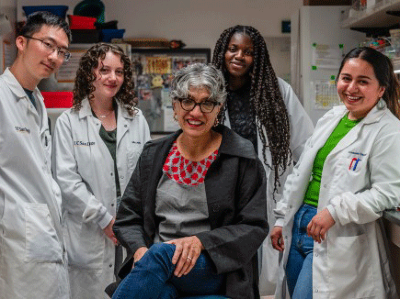

Dorceta Taylor has a long history of firsts. In 1991, she became the first Black woman to earn a doctoral degree from the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies in New Haven, Connecticut. In 2014, she created the first comprehensive report for monitoring racial, gender and socioeconomic diversity in environmental non-profit organizations, foundations and government agencies. And in 2018, she launched the New Horizons in Conservation Conference for early-career professionals of colour. After more than two decades as an environmental sociologist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, she returned to Yale in 2020. Two years ago, she was named the Wangari Maathai professor of environmental sociology, the first endowed chair in the field named after a Black woman. Her newest book, the SAGE Encyclopedia of Environmental Justice, which is due to be published in July, is the world’s first such compilation, describing key events, institutions and people of colour in the environmental justice movement.

Was there a moment when you realized that part of your mission is to tackle racism, diversity and inclusion in science?

I did my early education in the 1970s in Jamaica, a former British colony and current member of the British Commonwealth. The students were all people of colour, except for a few white kids who lived on the island. Science was what we did. We sat exams set by the University of Cambridge, UK, and they were shipped back there to be graded. It never occurred to us that being a person of colour meant you could not do science. To my surprise and shock, when I attended my first biology course in the United States in 1980 at Northeastern Illinois University in Chicago, I was the only non-white student in the room.

Seeding opportunities for Black atmospheric scientists

That was my first ‘a-ha’ moment. I asked the professor where all the other Black students were, and he said that Black people were not interested in the environment — a response that changed my life’s trajectory. My take was: “I’m going to prove this is wrong.” I decided to demonstrate that people of colour have an interest in the environment and know something about it, and that the reason for their absence is not a lack of interest or knowledge. One of the things I do now is to maintain a mentorship network for young people. All the programmes I run are multiracial, multicultural, multi-gender. I don’t want to turn around and discriminate against other people, because I know what it feels like.

What is the great passion that has driven you as a scientist?

I want to make a difference. I often think to myself, “What happens after I leave this Earth? Will I have made a change to anything?”

I spend an awful lot of time doing work to reach back and help others coming up behind me. Through grants from organizations such as the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation and the JPB Foundation (now known as the Freedom Together Foundation), I have funded 470 internships for undergraduate and graduate students, and almost all of those students have stayed in environmental conservation. In 2018, I started the New Horizons in Conservation Conference, which brings together undergraduate and graduate students, as well as professionals from universities and grassroots organizations, to focus on diversity in the environmental movement. During my time analysing the percentage of people of colour working at almost 200 environmental institutions and organizations, we have seen the numbers increase, but not by as much as we think they could. Where we don’t see as much change is at the highest levels of leadership — the president, or chair of the board. Those positions are still very white- and male-dominated.

Is there one thing from your career that you wish you could go back and do differently?

Early in my career, I had opportunities to leave the University of Michigan and go elsewhere, but I stayed for 27 years. I stayed because we were building the first environmental justice bachelor’s and graduate degree programmes in the country. And we had a number of people there doing exciting work. I also didn’t want to disrupt my children’s lives. But I have often wondered, what if, after five or so years at Michigan, I had segued. What would that look like now? I had opportunities to work in government and at a number of other places. I probably would take a bit more advantage of some of those opportunities to see what could happen.

Who was your biggest influence and why?

I had my white colleagues walk in a Black student’s shoes for a day

For a lot of Black women in my field, it’s very hard to pinpoint mentors because we are the trailblazers. I was the first Black woman to be hired in a tenure-track position in the University of Michigan’s School of Natural Resources and Environment. Women were taught to find a really great, powerful white male mentor. Guess what? They might offer a little help along the way, but they take care of themselves. I did admire environmental movement pioneer Rachel Carson because she, too, was a trailblazer, as one of only a few women working as a professional scientist at the US Fish and Wildlife Service in the 1940s. She was ridiculed, but she believed in her work and nothing on the planet could tell her she was wrong.

How have you dealt with racism and discrimination in your professional life?

Racism and bias exist in many forms, and have occurred at every stage of my life. I have to produce more work to be seen as equal. There were colleagues who said my work was no good. And I’ve had peers who published only one article a year. If I had that track record, I would never have been awarded tenure. One of the reasons my books were single-authored very early in my career was so that no one could say I didn’t do the work. My first book was written while I was undergoing chemotherapy for cancer. I wouldn’t let the nurses give me drugs that make you sleepy because I had to finish that manuscript. That book — The Environment and the People in American Cities, 1600–1900s: Disorder, Inequality and Social Change, published in 2009 — proved that I had what it takes.

What do you think of critics who say that diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) work is wokeness run amok?

Detractors are not going to get rid of DEI or environmental justice. That’s because white women and other groups have benefited more from DEI than Black people have. Many of us are waiting for people to realize that without that broader call for DEI, many white women, Jewish students and working-class individuals would not now have positions in universities.

Collection: Changemakers in science