Scientists don’t need to be superstar public performers like Taylor Swift, but they can learn from show business.Credit: Carlos Alvarez/Getty for TAS Rights Management

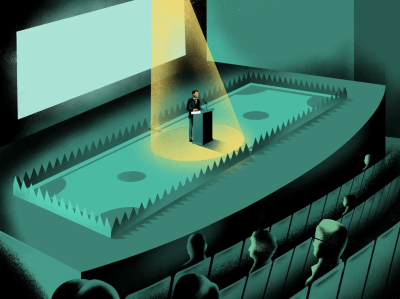

You’re at a conference. The lights are low, it’s the last speaker of the day, engagement has hit rock bottom and the audience completely tunes out. Phones come out and everyone is running the clock down; the speaker even apologizes for getting in the way of the networking drinks.

Re-imagine this setting as a gig: the lights are low, it’s the last act of the day, the band walks onto the stage, engagement goes through the roof and the audience explodes with excitement. No one wants it to end. In fact, the artist returns for an encore.

And now ask yourself, could the energy felt at a concert be recreated in a conference hall?

I research and teach immunology at Imperial College London and have also dabbled in public engagement as a popular-science author, so a chunk of my job focuses on public speaking. I have even tried stand-up comedy (the audience laughed, sometimes in the correct places). I also love live music. But the question is, what can researchers learn from performers to improve science talks?

Why scientists talk

Conference talks are a key feature of scientific careers. An invitation to give a keynote presentation at a reputable international conference is seen as a marker of esteem and ticks boxes for tenure and promotion. The extent to which a person’s ability to engage audiences is taken into account when selecting speakers is debatable — people are chosen for having ‘an interesting story’, which isn’t necessarily the same as the ability to tell an interesting story.

Talks don’t just raise an individual’s profile; they can be a platform to highlight a team that also contributed to the work. A great talk will advertise your laboratory, department or institution. To put it simply, if you are doing cool work (and you can explain it in a cool way), you might attract cool people to come and do it with you in a virtuous cycle.

Scientific bedlam at the world’s weirdest and wildest research conference

Beyond self-publicity, the point of science talks is to inform, educate and inspire others. In a research ecosystem that increasingly churns out overwhelming numbers of papers, scientific presentations are an important method of highlighting your work to a wider audience. And often, they can help you to engage with a broader circle than your own. We are all somewhat habitual in the papers that we read and the journals that we browse, and often the best ideas cross-pollinate from other fields. Moreover, a good talk can advertise stories to journal editors, who might be more open to a paper that is based on a talk than to one that lands in their inbox without context.

On a selfish level, if you’re an in-demand speaker, you are more likely to be invited to better conferences in nicer places. International travel, and the chance to meet other scientists and hear their research, is one of the great perks of a career in science. And being a speaker can give you kudos — which might open up conversations and collaborations with other speakers.

All of these benefits can be magnified if you knock the talk out of the park, and just as easily negated if you grind your way through your slides in a dull, monotone voice. But scientists are not necessarily natural performers. So, are there some lessons that can be learnt from performance artists?

As well as drawing on what I have observed through 25 years of snoozing through seminars and going to gigs, I reached out to actors, singers and comedians to get some tips from them.

Don’t lose the crowd

It is much easier to lose an audience than it is to win them back. By the time people have started checking their e-mails, they are as good as gone until the next speaker. They need to be gripped from the beginning. This starts when you are backstage. My colleague Robin Shattock, a vaccine researcher at Imperial College London, listens to ‘pump up’ music — such as ‘The Eye of the Tiger’ by Survivor — before public speaking. ‘Lose Yourself’ by Eminem works for me.

Lowlands: where science meets music

One way to lose the audience before you’ve even begun is by fiddling with cables onstage. Check your set-up in advance and make sure that the IT works — fumbling around with HDMI cables and looking for an adaptor for your laptop is unlikely to endear you to the crowd.

The introduction also plays a part in capturing the audience. Sometimes we have the ‘advantage’ of being introduced as a speaker. This does contextualize the talk, but I’m not sure that a concise summary of a CV necessarily fires up the audience. It’s worth considering what you share in the short bio you provide to the conference organizers — does it matter that you have worked at an institution for 25 years? Would it be better to describe your expertise?

Once you start, you need to own the stage. Don’t be apologetic about what you have to say — people are here to listen to you. If they have turned up, they have some basic level of engagement in your talk. Repay that engagement with confidence. Actor and former stand-up comedian Ben Willbond told me that “the audience needs to know they are in a safe pair of hands. If you watch a nervous, novice stand-up, they almost always lose the audience members, who can sense the speaker is not comfortable. When you are confident and in control, the audience relaxes and buys into what you are selling them”.

Willbond compares the ability to control a room to a ‘muscle memory’ that needs to be learnt and practised, so that it happens without conscious thought. “When speaking, engage the audience by looking up from the podium and into every corner of the room,” he advises. “That way, you then fill the stage.”

How to know whether a conference is right for you

Steve Cross, a London-based comedian and science communicator who runs courses to train academics to become better speakers, gave me the advice to “never stand behind the lectern. Come out and see how much better everything gets”. If you want to own the space, you need to be in the space. Movement and hand gestures can be important for this. I’m a fairly mobile speaker and have been known to knock things off lecterns, followed by the odd expletive. I’ve learnt to work this into the whole presentation package; when I’ve tried to rein in my movements, I expend too much energy on standing still and lose the flow. If movement is natural to you, incorporate it, because it gives character (as long as it’s not so extreme that it becomes distracting). However, be mindful of the microphone set-up — static microphones tie you to the spot more than mobile ones do.

Tone of voice is also important — try to vary it. Sounding too excited is just as bad as too bored. If you are excited about everything, then it’s hard for people to re-engage with the talk if they lose the thread. For example, when listening to sports on the radio, I tune back in when the pitch changes because something noteworthy might have happened. And if you insist on saying ‘interestingly’, make sure that the thing you are describing is actually interesting.

In a perfect world, a talk would be written from scratch, with the narrative chosen first and then the slides created next. But if you are upcycling an old talk, as all academics do, try to think of the flow and whether the slides you have resuscitated actually tell the story that you want. This is comparable to a band’s set list: switching between crowd-pleasers and new songs. A long string of data-heavy slides might lose the audience, so throw in images, jokes, asides and remarks to keep people attentive.