Experimental apparatus

All experiments were conducted in a 6–8 multi-anvil apparatus with 32 mm edge length WC cubes featuring 11 mm truncations and 18 mm edge octahedra, calibrated against the transitions of quartz–coesite, garnet–perovskite in CaGeO3, and coesite–stishovite. The assembly consists of a Cr-doped MgO-octahedron, a zirconia sleeve, a stepped graphite furnace, inner MgO parts and a PtRh B-type thermocouple. Full details, including pressure calibration, are provided in ref. 24. Based on previous experience with similar temperatures and melt compositions, equilibrium is typically achieved within 1–2 h. Consequently, our run times ranged from 2 h to 8 h, increasing with decreasing temperature. The starting mixtures were loaded into Re capsules folded from foil, placing a thin graphite layer at the bottom and top. These were then inserted into a Pt capsule, which was welded shut to contain the volatiles. The graphite–CO2melt pair yields the appropriate oxygen fugacity for redox melting, in which C0 oxidizes to CO2.

Starting compositions

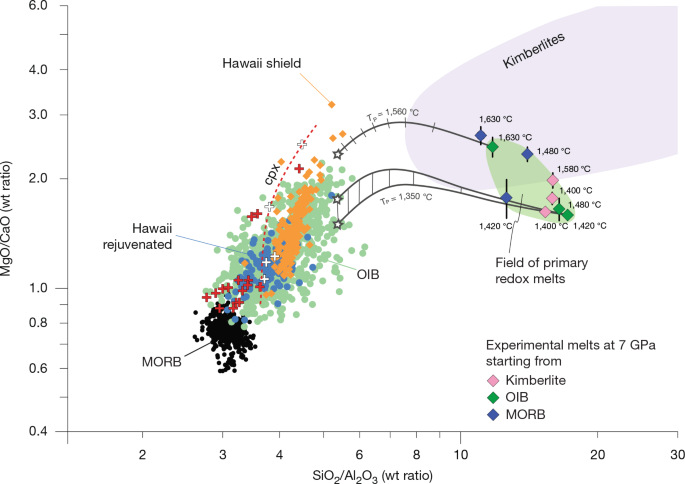

The experiments (Extended Data Table 1) equilibrate erupted surface melts with a lherzolite mantle at 7 GPa and temperatures of 1,420–1,630 °C. These conditions correspond to mantle potential temperatures (TP) of 1,350–1,560 °C, encompassing a typical mid-ocean ridge adiabat15,16 and an excess temperature of 210 °C, similar to the hottest mantle plumes32,33. Initial starting materials (Supplementary Table 1) include an average primitive ocean-island basanite (APB, see below) and an average of close-to-primitive MORBs, corrected for olivine fractionation (MBB). The OIB composition contains 5.4 wt% CO2 and 1.9 wt% H2O, based on melt inclusion data20. For the MORB, we selected the maximum observed CO2 content of 1.0 wt% as in the popping rocks19 and 0.5 wt% H2O, which is in the upper range of the MORB average (0.28 ± 0.24 wt% H2O; ref. 30). As erupted melts are largely degassed, reconstituting their volatile concentrations was necessary. Moreover, we extended our previous study on kimberlites31 to 1,580 °C, using a 1,400 °C experimental melt31 derived from a starting bulk composition with 7.5 wt% CO2 and 3.5 wt% H2O (JER1555).

All starting compositions were mixed by weight from previously dried chemicals, that is, SiO2, TiO2, Cr2O3, NiO, MgO, Al2O3, MnO and Na2SiO3, and from synthetic leucite, wollastonite, apatite and fayalite. All iron was present as FeII in the starting material. H2O and CO2 were introduced as Mg(OH)2, synthetic CaCO3 and natural magnesite. Powders were mixed in an agate mortar and homogenized in alcohol in a planetary mill. The starting materials were then kept in a desiccator and again dried at 110 °C before use.

Iterative forced multiple saturation experiments

The starting melt compositions were iteratively equilibrated with a four-phase lherzolite (olivine, orthopyroxene, clinopyroxene and garnet) modelled after peridotite KLB-1. Capsules were loaded either in a sandwich configuration with the melt placed in between two layers of synthetic powders representing mantle peridotite or as homogeneous mixtures of both components. Multiple iterations were necessary to (1) saturate the melt in all four lherzolite mantle phases and (2) to obtain large melt pools rather than interstitial melts (see Supplementary Fig. 1 for back-scattered electron images of the experiments). Melts rich in CO2 + H2O rarely quench into glass but rather form intergrown crystallites, requiring measurement areas larger than the crystallites to ensure accurate melt compositions. To address these challenges, subequal melt/peridotite starting proportions are required, and a suite of 13 and 11 experiments were conducted on the MORB and OIB compositions, respectively, to obtain equilibrium melt compositions at 1,420 °C, 1,480 °C and 1,630 °C (7 GPa). During these iterations, the peridotite component was adjusted by modifying the relative proportions of olivine, orthopyroxene, clinopyroxene and garnet, counteracting complete dissolution of any single mineral. Simultaneously, the melt composition was progressively refined (MBB → MORB2 → MORB10 and APB → OIB5 → OIB11; Extended Data Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1) until saturation in all four mantle minerals was reached and mineral compositions closely resembled those found in the mantle. A further experiment was run on a kimberlitic composition at 1,580 °C, which is complemented by the 1,400 °C melt composition previously obtained for kimberlites using a similar method31.

Preparation of experimental run products

The CO2 + H2O-bearing melts quench into a mixture of clinopyroxene, calcite and Na-rich interstitial carbonate-rich material and some interstitial voids, well observable (see detailed images in Supplementary Fig. 1). When left in the open, this quench material grows whiskers of several mm length within hours or days, leading to the destruction of the experimental charge. Thus, all preparation of the experimental run products was done minimizing the presence of humidity and avoiding water. Samples were exclusively handled in a purpose-built glove box that maintains a <2% relative humidity environment. Grinding and polishing were achieved using first dry SiC abrasive paper and then dry diamond powder. The very final polish was done using kerosene, after which samples were immediately coated and loaded either into the scanning electron microscope (for first imaging) or electron microprobe (for element quantification). Immediately after measurement, samples were impregnated with an epoxy droplet, protecting them from humidity. For any re-measurement, the polishing procedure was then repeated.

Experimental textures

To measure melt compositions, large melt pools are required. The low-viscosity melts migrate into the warmest part of the capsule, such that they form a girdle or belt in the equatorial region of the capsule or, when melt fractions are large, the crystals are found in an hour-glass-shaped zone at the colder ends of the capsule. These textures resulted irrespective of whether a homogeneous mix or a layered melt-peridotite starting configuration was used.

Melt interstitial to equilibrium minerals quenches into a combination of growth rims on equilibrium silicate minerals and sparitic intergrowth, leading to an overestimation of carbonate content when measuring the interstitial quench crystallites only. Large melt pools quench to fine-grained (with crystallites of typically 3–30 μm) or even glassy quench textures in their centre, and the margins of the melt pool develop coarse quench with abundant voids between the larger quench crystals (typically 50–150 μm). Whenever possible, we thus measured the fine quench. Experiments without any melt pools were discarded. Supplementary Fig. 1 provides an overview of the entire capsule for each experiment (polished to the centre axis, oriented E–W in the images) and detailed images of the quenched melt and the mineral-rich region.

Electron microprobe measurements

Mineral and melt compositions were measured with a JEOL JXA-8230 electron microprobe equipped with five wavelength-dispersive spectrometers and one energy-dispersive spectrometer. For minerals, 15 kV and 20 nA and a focused beam were used. For melt analyses, a maximum size defocused electron beam (20 μm) and 4 nA beam current were used. Most mineral and melt compositions were averaged from 5 to 25 measurements (Supplementary Table 3). Calibration standards included albite (Si and Na), anorthite (Al and Ca), forsterite (Mg), fayalite (Fe), synthetic rutile (Ti), chromite (Cr), microcline (K), synthetic pyrolusite (Mn), synthetic bunsenite (Ni) and apatite (P). Furthermore, natural hornblende and basaltic glass standards were used to monitor the accuracy of the calibration.

Melt compositions in terms of volatiles and alkalis

Melt compositions are given as measured by electron microprobe in Supplementary Table 2. CO2 and H2O cannot be directly measured in the quenched melt, and, despite completely water-free preparation of the experimental charges, measured alkali concentrations in the melt fall 20–50% below the values expected from mass balance. Thus, CO2, H2O, Na2O and K2O concentrations in the melt were determined from mass balance. Using the perfect incompatibility of CO2, H2O and K2O, we calculate their contents in the melt using, for example, CO2melt = CO2bulk/melt fraction. For Na2O, compatible in clinopyroxene and present in minor amounts in garnet, the mineral Na concentrations were considered when mass balancing for Na2Omelt. This approach yields experimental melt alkali contents, from which we determined DNacpx/melt. Using this partition coefficient, we then calculated the Na2Omelt that would be in equilibrium with a lherzolitic clinopyroxene containing, on average, 1.27 wt% Na2O (ref. 55), thus simulating the incipient melts as they would occur in fertile mantle (Table 1; original measurements in Supplementary Table 2). In general, CO2 and H2O estimates from mass balance closely match those derived from the difference-to-100 method from electron probe microanalysis, with discrepancies mostly within ±2 wt%. Discrepancies up to −5 wt% were encountered when either the melt quench was relatively coarse-grained or quite porous, or the surface was irregular—all factors leading to lower microprobe totals. Finally, the mass balance assumes a closed system, although some leakage of hydrogen through the capsule walls is possible. Nevertheless, this leakage leads to a net Fe oxidation and hence increase of XMg in all phases, which is not observed. We thus posit that hydrogen loss is minor.

Compilation of natural and experimental data

The experimental melts are compared with 747 primitive OIB compositions selected from the GEOROC (Geochemistry of Rocks of the Oceans and Continents) database, using 0.65 < XMg < 0.75 and 200–700 ppm Ni as main criteria56, singling out the rejuvenated (n = 123) and the shield stages of Hawaii (n = 225). For the starting material, an average was taken from the 13 ocean islands, which have >10 primitive melt compositions, excluding the tholeiitic shield stage of Hawaii. The MORB starting composition represents a composite average using analyses with XMg > 0.6 from the largest available MORB compilation57, corrected for equilibrium with mantle olivine of XMg = 0.89 by stepwise addition of olivine (MBB). In detail, the fine-tuning of the initial starting compositions is inconsequential, as these compositions were equilibrated with the four-phase mantle lherzolite—that is, they adjust themselves to equilibrium with the peridotitic mantle. Yet, the closer the starting material to the equilibrium melt composition, the fewer iterations are required.

Kimberlitic rocks do not represent melt compositions, but the product of low-degree asthenospheric mantle melting, lithospheric contamination, degassing and alteration on emplacement, the latter two removing almost all Na2O (refs. 36,41). The kimberlite fields in Figs. 1 and 2 and Extended Data Fig. 1 are derived from a compilation of coherent kimberlites58. We use the 50% envelope of the kernel density distribution of these data to exclude the most altered and modified samples.

Apart from our own experimental data, we plot the volatile-free peridotite melts at 1 GPa (refs. 59,60) (MgO/CaO ≈ 1) and at 3 GPa (ref. 26) (MgO/CaO > 1.5) to degrees of melting at which clinopyroxene melts out, which exceeds by far the degrees of melting relevant for OIBs and MORBs (Fig. 1).

Modelling asthenospheric melt evolution from 7 GPa to 3 GPa

We model the evolution of the 7 GPa OIB-type melts to the characteristic asthenosphere–lithosphere boundary (LAB) depth of about 90 km (ref. 39) for oceanic crust aged >120 Ma (as, for example, applicable to Hawaii, the western Pacific, Cape Verde and the Canary Islands). For a potential temperature TP of 1,560 °C, representing plumes with 200 °C excess temperature, we start with the 1,630 °C OIB melt with 7.3 wt% CO2 (corresponding to about 1.5 wt% melting) and model melt evolution to a melt fraction of 10 wt%, as estimated for the Hawaiian shield stage61. This increase would reduce CO2melt to about 1 wt%, consistent with the upper bound found in Hawaiian shield melt inclusions62. For comparatively cooler plumes (for example, Cape Verde and Canary) with a TP of 1,350 °C, we model the evolution of the 7 GPa, 1,420 °C OIB-type melt with 15.4 wt% CO2 (corresponding to about 0.5 wt% melting) to a melt fraction of 4 wt%, based on CO2 contents of 3–5 wt% in primitive melts of these hotspots29,63.

For a TP of 1,560 °C, we apply the melting equations and mineral compositions for dry peridotite melting26 obtained at similar temperatures, which are, for melt fractions ≤10% (in wt units): 26 olivine + 50 clinopyroxene + 24 garnet = 100 melt (7 GPa) and 7 olivine + 68 clinopyroxene + 25 garnet = 84 melt + 16 orthopyroxene (3 GPa).

Using these equations for our moderately volatile case is justified as CO2 and K2O in the melt remain fully incompatible from 7 GPa to 3 GPa. Na2Omelt concentrations are calculated using melt–clinopyroxene partitioning, with adjustments at melt fractions >4% for the decreasing Na2Ocpx. For a TP of 1,350 °C, we use the same melting equations, as no others are available, but mineral compositions as adequate for 1,420–1,350 °C, 7–3 GPa (this study; refs. 21,64). The results are aggregate melts that approximate the evolution of redox melts in the asthenospheric melting column from 7 GPa to an LAB at 3 GPa.

As melt fraction increases continuously from the depth of redox melting to the base of the lithosphere, we linearly combine the two melting reactions to reach 10 wt% and 4 wt% melt, respectively, calculating melt compositions stepwise in 0.01% increments. This approach is justified because melt compositions and melting reactions must evolve continuously with depth. In the absence of more information, a linear combination remains the best approximation.

Clinopyroxene Ca contents are a considerable uncertainty as the conditions for a TP of 1,350 °C straddle the flat pigeonite–high-Ca clinopyroxene saddle on the pyroxene miscibility gap. We therefore use different CaO contents of 13–16.5 wt% in clinopyroxene for 7–3 GPa (this study; refs. 21,64), producing a range of model melt compositions diverging in CaO and MgO/CaO (Fig. 1 and Extended Data Fig. 1).