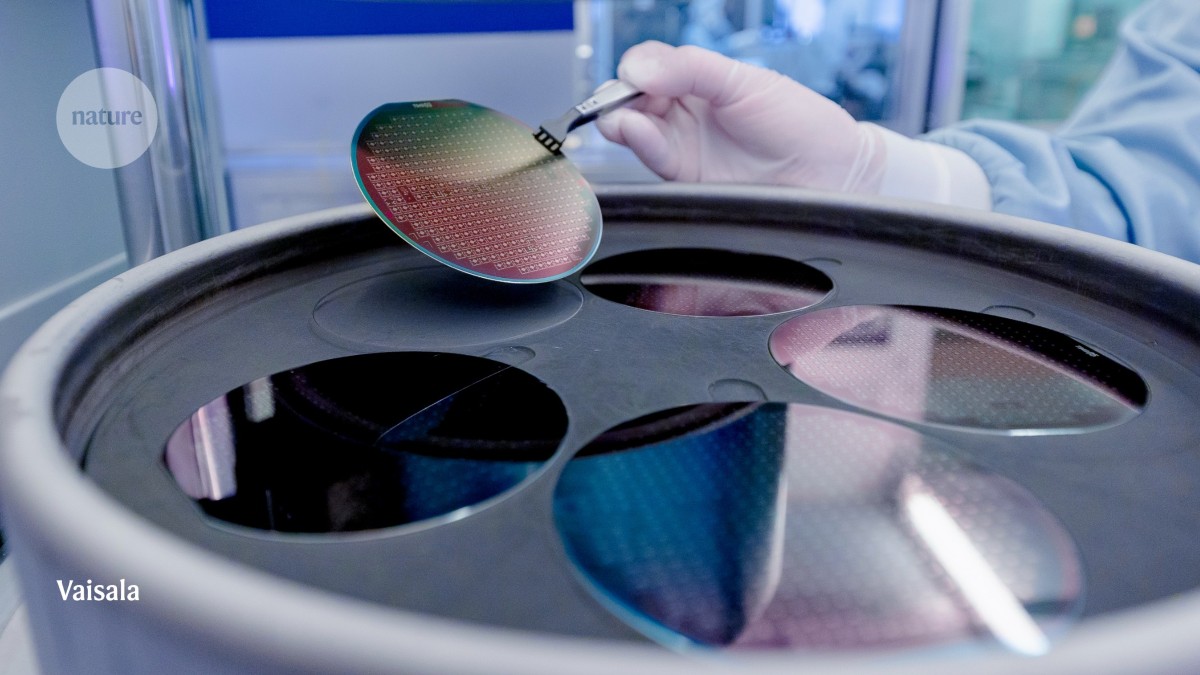

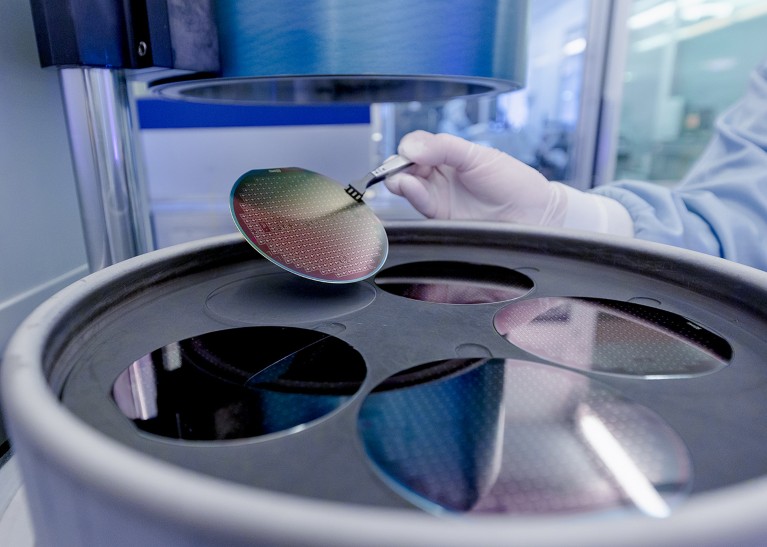

An employee at Vaisala holds a gas-sensor component that is being manufactured in the company’s clean room.Credit: Vaisala

Neuroscientist Tamara Stawicki woke abruptly to her mobile phone ringing shortly after 1 a.m. on 24 August 2025. After a brief conversation, Stawicki got out of bed and drove to a quiet car park. Casual observers might have wondered what she was up to as she strode purposefully into an imposing building at Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania, still wearing her pyjamas.

Nature Spotlight: Sensors

In fact, Stawicki was on a mission to save the lives of around 1,000 zebrafish (Danio rerio) in her laboratory. Similarities between lines of hair cells on the fish’s flanks and those in the mammalian inner ear enable her to use them as a model to study hearing problems in humans caused by some antibiotics and chemotherapy drugs. A sensor had picked up that the lab’s heating system had been knocked out by a power fault, triggering the call from campus security that put Stawicki in a race against time to protect the fish.

Sensors, like the one in Stawicki’s lab, have become commonplace. Lab managers investing in technology are more likely to be upgrading their current system than installing one for the first time. “Twenty years ago, monitoring labs remotely was seen as a luxury, whereas now many are on their second- or third-generation systems, so people have a better understanding of what information they can gather and what they can do with it,” says Han Weerdesteyn, chief commercial officer at XiltriX in Rosmalen, the Netherlands, which sells such systems.

Although researchers and their technical colleagues might know what to expect from a sensor system, there is still plenty for them to consider if they decide to upgrade. Do they, for example, just want to make a one-off purchase of hardware and software, or do they also want to subscribe to ongoing related services? Will new systems integrate with other technologies that they already use or interfere with them? And what about maintenance, technical support, data security, storage requirements and the need to calibrate sensors to ensure they are accurate?

Robots demonstrate principles of collective intelligence

Almost all labs already have sensors as part of building-management systems used to monitor and control heating, ventilation, air conditioning, power, lighting and security. The sensors used by researchers to keep track of their work remotely are sometimes described as environmental monitoring systems. Among the most widely used are those that measure relative humidity, light, room occupancy, differential pressure and gas quantities. Others can detect motion, open doors, whether the equipment is on, the presence of water or battery status.

Temperature sensors are bestsellers for companies that supply academic and industry labs: “Whether research is on physical materials, chemical reactions or biological systems, the outputs or behaviours are usually dependent on temperature, so devices that measure temperature are the most common sensors in labs,” says Hannu Talvitie, a technology strategist at Vaisala, a measurement-equipment company in Vantaa, Finland.

In some labs, data from sensors are still gathered manually, however this is time-consuming and might mean that problems are not spotted until it is too late. Increasingly, sensors automatically transmit information to a central hub through either wired or wireless networks. Software analyses the data, transforms it into user-friendly charts, graphs or dashboards, and uploads it to the cloud so it is accessible through phone apps or web platforms, triggering emergency alerts if necessary.

One of the reasons scientists use these systems is to avoid disastrous equipment failures. “It means I can sleep at night,” says Sebastiaan Mastenbroek, a clinical embryologist at the Center for Reproductive Medicine at the Amsterdam University Medical Center (UMC) and director of the research institute Amsterdam Reproduction and Development. Both the clinical unit, which stores around 250,000 patient samples and provides in vitro fertilization (IVF) services, and the research facilities have systems provided by XiltriX. These include sensors to monitor temperatures in freezers that store sperm cells, oocytes, embryos and testicular tissue biopsies; temperature, carbon dioxide and oxygen levels in incubators for embryo and cell cultivation; and equipment functioning and network connectivity. System failures trigger automatic calls to lab staff.

Mastenbroek received one such alert at around 1.30 a.m. one day in April 2018, causing him to make an emergency trip to his lab during a local power cut. He ensured that back-up power was in place to keep the clinical and research samples at the right temperatures. “It is hard to imagine a modern IVF facility without a monitoring system. For me, it is also a no-brainer to have one in your research lab,” he says.

AI on the horizon

Some monitoring systems go beyond simply raising the alarm in emergencies. Software company Elemental Machines in Cambridge, Massachusetts, aims to tell users not just when there is a problem, but also why — using artificial intelligence to analyse historical data. “We look at patterns of temperature changes leading up to a freezer alarm at 2 a.m. to tell you if someone just opened and closed the door ten times or the compressor is failing,” says Sridhar Iyengar, founder of and chief strategy and technology officer at Elemental Machines. “That means you know whether to go back to bed or to go take a look.”

Similar approaches can also be used to identify when equipment needs maintenance or technology is not suited to particular tasks. For example, the monitoring system in Mastenbroek’s lab recorded programmed temperature spikes, which are used to prevent ice forming, inside a refrigerator. This told Mastenbroek that it was not suitable for storing cell-culture medium. Elemental Machines generates what it calls “AI-powered health scores” for lab equipment based on sensor data, to spot changes before they become more serious.

Sensors helped Tamara Stawicki to prevent losses among her fish population.Credit: Amy Badillo

Automated continuous data collection using sensors can help scientists to understand more quickly why their research might be going wrong. Weerdesteyn says that he learnt the hard way that access to some basic data can be the difference between scientific success and failure during his master’s degree programme at Radboud University in Nijmegen, the Netherlands. He was studying the role of a nucleotide sequence that occurs repeatedly in tobacco plants when his experiments suddenly stopped working. It took around three months to work out that this was because the catalysts he was using in PCR reactions had become inactive when a colleague left a freezer door open. But by that point, he had run out of time, and his research project failed to yield results.

Weerdesteyn says that this ended his career as a scientist and inspired his work providing monitoring systems to others. Without sensor information in the lab, you’re unaware of everything that is going on, he says. “With it, when things go wrong, you at least know where to start looking. The ability to see which parameters have changed retrospectively can improve your research over time.”

There could also be financial benefits to installing reliable monitoring systems for labs seeking grants from private-sector partners, such as pharmaceutical companies, Weerdesteyn says. “Having access to sensor data means researchers can demonstrate they can produce good quality, consistent results, so they are more likely to be able to obtain grants from industry.”

There are some other key considerations for researchers and lab managers contemplating whether to invest in sensor-based monitoring or choosing between different systems. High up on the list is ensuring that any data generated is accurate. “Bad data is worse than no data,” says Talvitie. “Reliable equipment and its regular calibration are essential if you want measurements you can trust.”