You have full access to this article via your institution.

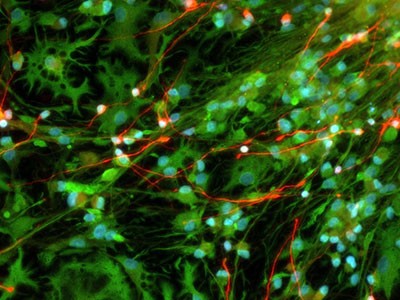

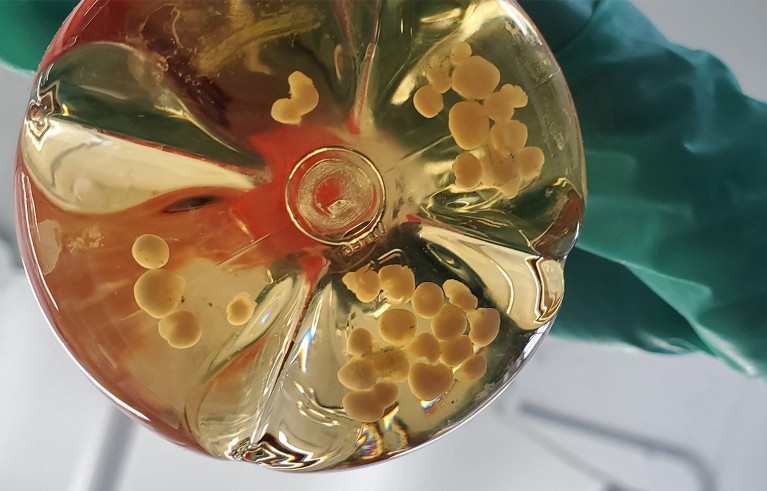

A culture flask containing human brain organoids.Credit: Science History Images/Alamy

When the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), the world’s largest funder of biomedical research, announced on 22 January that it would stop funding most research involving human fetal tissue, many scientists were dismayed by both the timing and the reasoning.

NIH ends support for most human fetal-tissue research – dismaying some scientists

“This decision is about advancing science by investing in breakthrough technologies more capable of modeling human health and disease,” NIH director Jayanta Bhattacharya said in a statement (see go.nature.com/4by2ekk). Those technologies, the statement added, include computer modelling, organ-on-a-chip systems and complex 3D cell cultures called organoids.

But developmental biologists say that these tools are not yet able to model human health and disease accurately1. That is also the view of the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) in Evanston, Illinois. In response to the NIH decision, the ISSCR said: “Research with human fetal tissue (HFT) and HFT-derived cell lines has been integral to biomedical progress for nearly a century” (see go.nature.com/4tes8mn).

It added: “This research has contributed to fundamental advances in understanding human development, infertility, infectious diseases, and chronic and neurodegenerative conditions.” The ISSCR is urging the NIH to reconsider its decision. Fetal tissue is essential to studying diseases, and as a benchmark for evaluating technologies such as organoids. The NIH must think again. Hindering this research will slow the development of replacement technologies.

The NIH decision prohibits the awarding of federal funding to studies for which fetal tissue has been obtained from elective abortions, although the agency will continue to fund research on tissue from miscarriages and stillbirths. However, scientists say that most work is done with tissue from elective abortions, in part because such tissues often provide a more accurate and representative source of information about healthy development than do those from miscarriages and stillbirths.

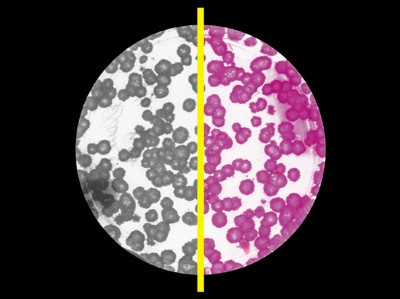

Technologies for studying human fetal tissue are improving rapidly. Techniques that enable researchers to measure gene activity in individual cells have enabled unprecedented projects to map the cells in an entire tissue. Large research consortia have been cataloguing cells in organs by creating ‘cell atlases’ of both adult and fetal tissues2. Those atlases, however, are not yet complete. The human brain, for example, contains some 86 billion nerve cells, and mapping them remains a formidable task.

The truth about fetal tissue research

Technological alternatives to human fetal tissue are also improving. One is the organ-on-a-chip system, in which human cells are grown on a device designed to mimic how the organ functions and develops. But a 2025 report from the US Government Accountability Office concluded that such methods have not yet been vetted sufficiently by comparing these devices to real organs to verify their accuracy and reliability (see go.nature.com/46coew4).

The NIH statement also mentions organoid cultures as alternatives to research involving fetal tissue. This technology is advancing: some organoids can grow their own blood vessels3 and form networks with other organoids4. Even so, comparisons of gene expression between organoids grown in the laboratory and the tissues they are meant to model have highlighted substantial differences. Organoids produced using distinct approaches result in varying levels of accuracy. Studies of neural organoids, for example, have shown that not all of them fully mirror, or recapitulate, the gene-expression patterns seen in brain tissue fully5,6. Although organoids are becoming more complex, they are still simplified systems, and, in many cases, lack some of the cell types and the structural complexity necessary for modelling diseases.

We recognize the necessity of using alternatives to sensitive materials such as tissue from human fetuses whenever possible. The consensus in the community and the learned bodies that represent it is that although such alternatives are being developed and characterized, they do not currently mimic fetal cell biology faithfully. The development of these tools needs the US federal government to continue to support projects that aim to standardize, validate and improve such methods.

This means that, for now, fetal tissues are needed to provide a benchmark for the complex tissues and interactions between cells in organs. The NIH prohibition is likely to smother crucial basic and medical research. Restricting fetal tissue research will slow the progress of the alternatives that all parties want and need.