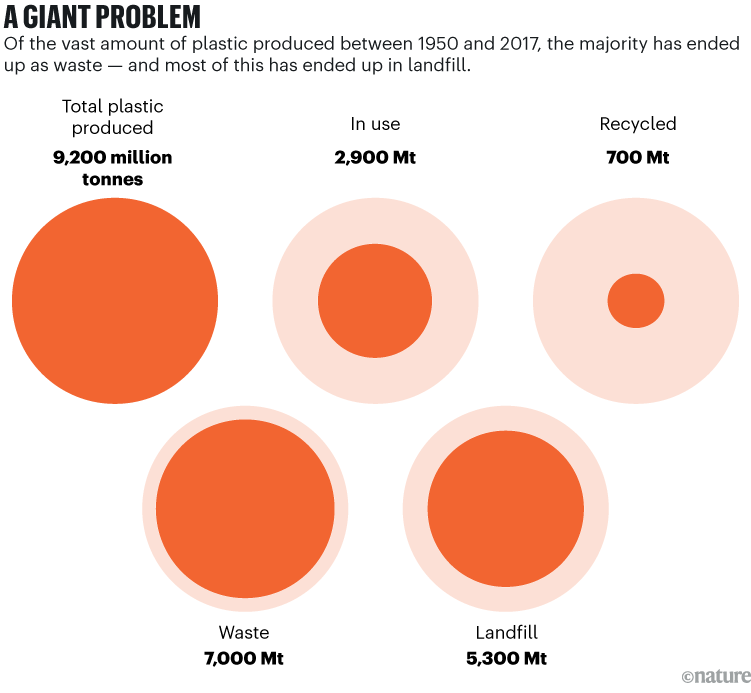

Plastic pollution is a scourge of land and seas, and has reached Earth’s remotest regions1. Failure to deal with it could mean exposing ecosystems and people to harmful microplastics, nanoplastics and chemicals2 for centuries. Transported globally, including by rivers and the wind2, plastics are intertwined with issues around equity and justice. Many of the communities that are most harmed by plastic pollution, for instance, are those that are least responsible for producing it3 (see ‘A giant problem’).

Plastics’ persistence over time, ability to cross borders and impacts on climate change demand international regulation. Production alone is responsible for around 5% (2.24 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent) of global greenhouse-gas emissions, compared with the 1.4% (0.6 GtCO2) of emissions that stem from aviation4. In recognition of this, in March 2022, the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA), the organization’s highest environmental decision-making body, established the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) to develop a global treaty to end plastic pollution, including in the ocean.

Source: R. Geyer in A Brief History of Plastics 33–47 (Springer Nature, 2017).

Yet, following six rounds of negotiations over more than three years, delegates from 184 member states remain deadlocked. After ten days of debate at a reconvened fifth session in Geneva, Switzerland, in August 2025, no agreement on a treaty could be reached.

As official observers of the INC process (P.E. and L.D.S.) and advisers among the roughly 20-person German delegation (M.B. and A.J.), we have become convinced that the INC process — as currently designed — won’t succeed. But on 7 February, a new INC chair will be elected. Several key procedural changes, if implemented and overseen by the new chair, could break the impasse and pave the way for an effective global plastics treaty.

Why the deadlock?

Creating a global plastics treaty was never going to be easy, as many experts have pointed out5.

First, negotiators have been trying to converge on rules about regulating plastics globally within a complex and fragmented pre-existing governance landscape for waste and pollution6.

What now for the global plastics treaty?

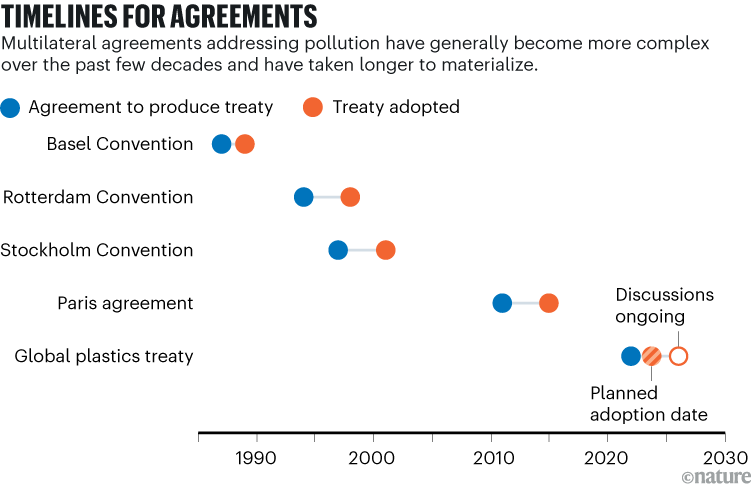

Although far from adequate to deal with the growing problem of plastic pollution, various conventions already regulate pollution from ships and the cross-border movement and trade of hazardous substances and waste, including some plastics. These include the London Convention, which entered into force in 1975; Annex V to the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, which entered into force in 1988; the 1992 Basel Convention; and the Rotterdam and Stockholm conventions, both of which entered into force in 2004.

Meanwhile, at regional and national levels, several countries have introduced policies that affect the production or use of plastics (upstream interventions) or the collection, incineration, recycling or repurposing of plastic waste (downstream interventions).

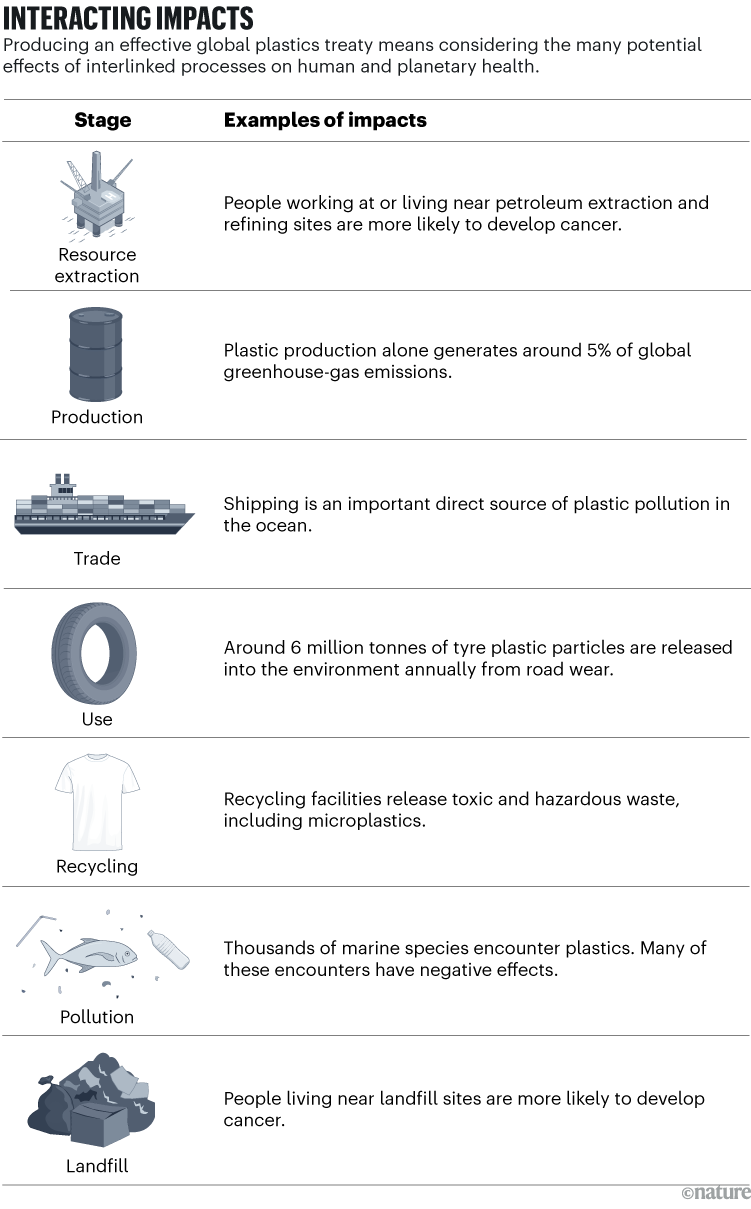

Second, partly because most pre-existing multilateral environmental agreements regulate the downstream components of the life cycle of plastics, the INC was mandated to take a more precautionary approach and consider the full life cycle. But addressing plastic pollution holistically means considering all sorts of interlinked and politically fraught issues — from resource extraction, production, trade, use and disposal to financing and equity.

Third, countries tend to take different positions on the various aspects that need to be debated, depending on the drivers of their economies.

Plastic waste covers the Jambe River in West Java, Indonesia.Credit: Dasril Roszandi/NurPhoto via Zuma Press

Some economies that are heavily dependent on oil and gas, such as the United States, Russia and Arab states, generally support regulating waste management — so focus on downstream interventions. Other countries, such as those with significant Indigenous populations, small island states and coastal states7, many of which are disproportionately affected by plastic pollution3, support regulations across the entire life cycle of plastics. These policies might involve banning the production of certain plastics, the regulation of chemical design, or financial aid to bolster collection infrastructure, recycling and the remediation of existing pollution in low- and middle-income countries. Highly regulated industrial economies, including the European Union (EU), Norway and Canada, meanwhile, push for ambitious global standards to level the playing field and increase their access to international markets, while protecting human and environmental health.

Finally, there’s the problem of intense lobbying by industry. Fossil-fuel and petrochemical industry representatives have been present in growing numbers since the second round of negotiations. And some have used tactics, such as strong messaging on the benefits of plastics to delegates, to delay, weaken or derail measures, particularly those concerning caps on the production of plastics.

All of these challenges, however, are standard for multilateral environmental agreements. Similar difficulties, particularly with respect to member states pulling in different directions, were overcome before 198 parties ratified the Montreal Protocol to protect the ozone layer. The same was true before 196 parties adopted the Paris agreement by consensus in 2015.

In our view, the repetitive, fragmented debates that are typical of INC negotiations are largely the result of how the process has been structured and governed.

Pitfalls in the process

Three design flaws are proving particularly problematic.

Lack of prioritization and sequential decision-making. The document8 resulting from the 2022 UNEA meeting — UNEA Resolution (5/14) — states that the INC should address “the full life cycle of plastic”. But member-state delegates deliberately interpret ‘full life cycle’ differently, depending on their countries’ economic interests. In the reconvened fifth session, for example, some delegates argued that the term does not include extraction. Others maintained that it does not refer to health impacts (see ‘Interacting impacts’).

Likewise, UNEA Resolution (5/14) states that a global plastics treaty must “complement” existing agreements. But, to stall proceedings, some delegates have used the argument that a number of the problems posed by plastics are already being addressed (or could be addressed) by pre-existing regulations.

Environmental treaties are paralysed — here’s how we can do better

Certain delegations repeatedly argue, for example, that together, the Basel Convention (which controls the trade and disposal of hazardous waste, including some plastics) and the Stockholm Convention (which regulates persistent organic pollutants, meaning toxic chemicals) already address problems associated with plastics and related chemicals. But most plastics would not be defined as hazardous waste under the Basel Convention. Furthermore, only about 6% of the more than 16,000 chemicals that can be intentionally used, or that are unintentionally present in plastics, are regulated under the Basel and Stockholm conventions and the Minamata Convention, which came into force in 20179.

In our view, at the very least, priorities must be defined and decisions made about whether caps on plastic production, regulations on chemicals and products of concern, and financing schemes are to be included in the treaty early in the process, before subsequent decisions can be made.

Compressed timeline. The INC’s original remit was to deliver a global treaty by the end of 2024. This ambitious timeline for a complex treaty (see ‘Timelines for agreements’) has hindered prioritization and sequential decision-making, and has pushed negotiators to debate details before ensuring that everyone concurs on the basics.

Source: High Ambition Coalition to End Plastic Pollution

The timeline has also driven negotiators to debate interconnecting issues in parallel sessions. In one room, participants might be discussing caps on plastics production or bans on the use of certain chemicals. In an adjoining room, another group might be trying to tackle how plastic-waste management in low- and middle-income countries might be financed. Yet, in many cases, reaching agreement on one issue could help to do the same elsewhere. If an agreement to cap plastic production was reached, for example, countries with more-ambitious goals would probably be more willing to contribute financially to collection schemes and the funding of remediation. Currently, such countries do not support subsidizing waste management for escalating amounts of production.

Inadequate procedural rules. Whether co-chairs (delegates appointed to moderate discussions) have the authority to synthesize contributions and propose draft text is currently unclear. This makes the drafting process inefficient and laborious, especially when combined with other ambiguities around the process and the fact that there are parallel tracks of discussion. (Each discussion group can be focused on between 2 and 20 or more treaty articles.) It also means that considerable time is spent arguing about the INC process itself rather than about the contents of the treaty.

A lack of well-defined rules similarly obstructs the management of disputes. If two opposing positions emerge in a formal discussion group (called a contact group) and there is no way to reach agreement in the group, informal negotiations can take place without observers present. It is unclear, however, whether or how the ‘informals’ then affect the draft text, which further erodes trust and paves the way for yet more disagreement.

A raft of plastic waste in the South China Sea drifts onto a Vietnamese beach.Credit: Prisma/ Dukas Presseagentur/Alamy

Without adequate and transparent rules on procedure, more and more text that lays out ever-more nuanced positions on an issue will continue to be added to draft text. And some delegations will keep using the ‘nothing is agreed until everything is agreed’ mantra to stall negotiations.

Since the second INC session was held in Paris, delegates have been unable to agree even on a process decision — specifically, whether to allow, under well-defined circumstances, delegates to vote and decisions to be based on majority rule rather than on consensus. We became convinced at the reconvened fifth session in Geneva that the current structure of the INC process is not fit for purpose. During the fifth negotiation round in Busan, South Korea, delegates seemed to be converging on how to deal with discarded fishing gear. In Geneva, the text was opened up for discussion again, and because so much nuance was added, agreement broke down.