Ethics

This research complies with all relevant ethical regulations. The study protocol was determined to be not human subjects research by the Broad Institute Office of Research Subject Protection as all data analysed were previously collected and de-identified.

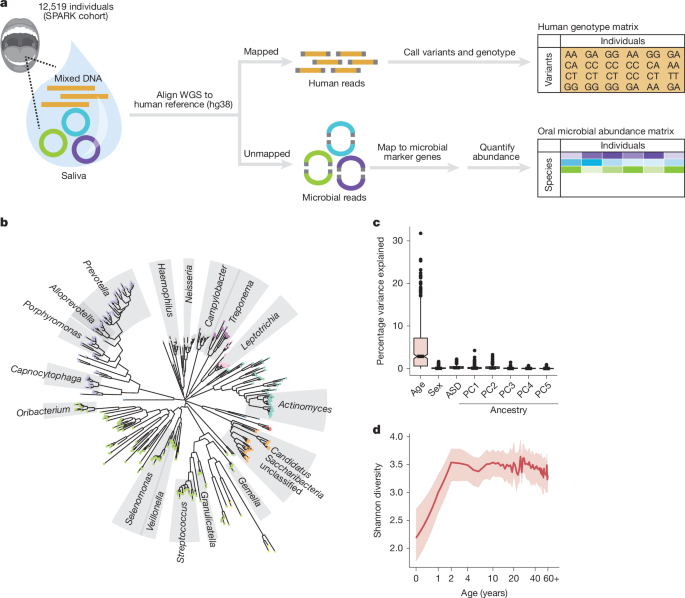

Quantification of microbial relative abundances from saliva WGS

We analysed saliva-derived WGS data previously generated for 12,519 individuals from the SPARK cohort of the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (SFARI)25. In brief, DNA extracted from saliva samples was prepared with PCR-free methods for 150 bp paired-end sequencing on Illumina NovaSeq 6000 machines. Reads were aligned to human reference build GRCh38 by the New York Genome Center using Centers for Common Disease Genomics project standards. Details of saliva sample collection, DNA extraction and sequencing were described in ref. 26 (which analysed data from sequencing waves WGS1–3 of the SPARK integrated WGS (iWGS) v.1.1 dataset; here we analysed WGS1–5, which included additional samples included in subsequent sequencing waves).

From the CRAM files previously aligned to GRCh38, we extracted all unmapped reads for subsequent generation and analysis of oral microbiome phenotypes. This retrieved a median of 67.5 million unmapped reads per sample ([35.9 million,126.1 million], quartiles), comparable with the total number of reads used for previous metagenomic characterization of human microbiomes71 and consistent with previous analyses of SPARK samples for oral microbiome profiling26,27. Unmapped reads were converted to compressed FASTQ with samtools (v.1.15.1) and then used as input for microbiome profiling using MetaPhlAn (v.4.0.6) with the vOct22 reference database. To evaluate robustness of these oral microbiome profiles, relative abundances of species in SPARK samples were compared with those from samples in the Human Microbiome Project72 by first subsetting to those profiled in both cohorts and then performing principal coordinate analysis using Bray–Curtis distance (Extended Data Fig. 1b).

From the relative abundance phenotype generated for each species by MetaPhlAn, we estimated the fractions of variance explained by covariates (age, sex, ASD and genetic ancestry PCs; Fig. 1c) using analysis of variance (finding the sum-of-squares for each covariate and dividing by the total sum-of-squares).

Generation of mPCs

Relative abundance measures of all microbes were first filtered to 439 entries corresponding to microbial species found in at least 10% of SPARK DNA samples. Rank-based inverse normal transformation across individuals was then performed for the abundance of each species. This transformation did not always produce values with mean 0 and variance 1 (due to large fractions of samples with zero abundance), so these were then scaled and centred for use as input to PC analysis to obtain 439 orthogonal microbial abundance principal components (mPCs) representing orthogonal axes of microbial variation.

Genotyping and quality control of human genetic variants in SPARK

Variant calling in SPARK was previously performed using DeepVariant (v.1.3.0) to produce sample-level VCFs from reads aligned to GRCh38 followed by GLnexus (v.1.4.1) to call variants jointly across the cohort. We performed a series of QC steps on the joint call set, starting by converting half-calls to missing and then excluding variants with >10% missingness using plink2 (v.2.00a3.6LM). Variants were further excluded if they had a minor allele frequency <1% or if they had a Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium exact test P < 1 × 10−6 with mid-P adjustment for excessive heterozygosity, leaving 12,525,098 common variants. Genetic ancestry PCs were generated by LD-pruning variants in 500 kb windows with r2 > 0.1 and then running plink2 –pca approx. No individuals were filtered for outlier heterozygosity after inspection in each genetic ancestry group. Variants were then filtered to those present in the TOPMed-r3 imputation panel to exclude those in regions of poor mappability to produce a final set of 9,618,621 common variants to test for association with oral microbiome phenotypes.

mPC-based GWAS of oral microbiome composition

A straightforward way to search for host genetic effects on microbiomes is to test human genetic variants for association with the abundance of each microbial taxon in turn10,11,12,13. However, we reasoned that a statistical test designed to aggregate evidence of pleiotropic genetic effects on many species in a microbial community could considerably increase statistical power32,33,34. To perform such a test in a scalable manner (efficient enough to test millions of human genetic variants), we made use of the decomposition of the microbial abundance matrix into 439 orthogonal mPCs. Specifically, we tested each genetic variant for association with each rank-based inverse normal transformed mPC, after which we summed the 439 test statistics obtained per variant to compute a single, combined association test for each variant (Fig. 2a; details in next section). Beyond increasing power to detect pleiotropic effects, the approach reduces multiple-testing burden by testing each genetic variant only once. We evaluated applying this approach to a subset of top axes of microbial variation (rather than all 439 mPCs) but did not observe a further increase in power, consistent with many axes of variation contributing association signal in this dataset (Extended Data Fig. 2f–p).

Details of GWAS of oral microbiome composition

We performed GWAS on each mPC phenotype using the linear mixed model implemented in BOLT-LMM to account for the family structure of the SPARK cohort30,31,73. Specifically, we ran BOLT-LMM using the –lmmInfOnly flag (as the non-infinitesimal mixed model provided a negligible increase in statistical power) with the following covariates: sequencing batch, age, age squared, square root of age, sex, percentage of mapped reads and the top ten genetic ancestry PCs. A single father without a recorded age was assigned the average age of other fathers in the dataset. AMY1 and PRB1 copy numbers were rescaled to a range of [0,2] and encoded as dosages for association testing.

To test a genetic variant for association with an effect on overall oral microbiome composition, we summed chi-square statistics across the 439 orthogonal mPCs and computed the P value based on a chi-squared distribution with 439 degrees of freedom. We computed P values using a one-sided test, analogous to how in linear regression, one-sided chi-squared test statistics are computed (corresponding to two-sided tests of z-statistics).

MDMR of oral microbiomes with selected genetic variants

We compared our test for genetic effects on oral microbiome composition with multivariate distance matrix regression (MDMR)33 as implemented in the MDMR R package36 (v.0.5.2), which finds significant predictors of multivariate outcomes by estimating the attributable amount of dissimilarity between samples. Rank-based inverse normal transformed relative abundances of the 439 most prevalent species (with or without initial centred log-ratio transformation) were used to generate the Euclidean distance matrix. MDMR was then run with the following covariates: sequencing batch, age, age squared, square root of age, sex and percentage of mapped reads. As genetic ancestry PCs frequently produced a singular matrix as a result of multicollinearity with individual variants, the top ten genetic PCs were first regressed from each tested variant (rather than including genetic PCs as covariates). The 11 loci identified from our mPC-based GWAS of oral microbiome composition were tested alongside 1,000 randomly selected variants on chromosome 1.

Stratified LD score regression for estimating enrichment of heritability at genes with tissue-specific expression

We observed that the same mathematical framework that enables partitioning of heritability by means of stratified LD score regression on summary statistics from GWAS of a single trait74 could be extended to analyse test statistics for association with oral microbiome composition (based on summing chi-squared test statistics across 439 mPCs). Starting from the representation of expected marginal chi-square association statistic for SNP i based on linkage disequilibrium with variants in categories Ck,

$$E[\,\chi _i^2]=1+Na+N\sum _k\tau _kl(i,k)$$

averaging across the 439 chi-square statistics for each variant gives

$$E[\bar\chi _i^2]=1+N\bara+N\sum _k\bar\tau _kl(i,k)$$

such that providing \(\bar\chi _i^2\) as input to S-LDSC generates enrichments corresponding to \(\bar\tau _k\). Averaged chi-square statistics per variant were used as input to munge_sumstats.py. LDSC was then run with baseline v.1.2, weights_hm3_no_hla as weights and previously described tissue-specific expression bins derived from Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project samples37.

GWAS of abundances of individual taxa

To avoid test statistic inflation from zero inflation and outlier values, relative abundance measures for each taxon were rank-based inverse normal transformed. Abundances of 1,262 taxa (of any phylogenetic level: species, genus, family and so on) observed in >10% of SPARK samples were then tested for association with host genotypes using BOLT-LMM. The top 20 PCs from PCA on 439 species observed at >10% prevalence (that is, the top 20 mPCs) were used as covariates to control for the largest axes of variation across samples, along with sequencing batch, age, age squared, square root of age, sex, percentage of mapped reads and the top ten genetic ancestry PCs. To test loci that might be associated as dominant/recessive rather than additive, BOLT-LMM was rerun using the –domRecHetTest flag.

To evaluate whether some of these associations could reflect compositional effects rather than being specific to the associated taxa, we computed an alternative set of taxon abundance phenotypes in which we took the centred log-ratio transform of relative abundances in each sample75 (after replacing zero values observed for a given taxon with the minimum non-zero value for that taxon, to allow computing geometric means). Centred log-ratio transformed values for each taxa were then tested for association with host genotypes using BOLT-LMM with the same covariates as above (Extended Data Fig. 4e).

For estimating effect sizes of specific genotype values such as FUT2 W154X genotypes (Fig. 2d), AMY1 copy numbers (Fig. 3c) or PRB1 copy numbers (Extended Data Fig. 3c), we used linear regression with the same covariates as above, encoding each genotype value (rounded if necessary) as a separate factor. The standard errors estimated by these regressions are slightly underestimated because they do not account for relatedness among SPARK participants, but we determined that this underestimation of standard errors was mild (~7% based on a ~14% inflation of chi-square test statistics computed using linear regression versus a linear mixed model for the 11 genome-wide significant loci (Supplementary Fig. 2)). To compare effect sizes in adults versus unrelated children, one child was randomly selected from each family in SPARK. BOLT-LMM was used to run linear regression on each of these subsets separately.

GWAS in UK Biobank

Starting from 488,377 individuals in the UKB SNP-array dataset43, individuals were excluded on the basis of the following criteria: 36,008 were removed to drop one relative in pairs of close relatives with kinship coefficient >0.0884, preferentially keeping individuals if they (1) reported having dentures or (2) reported not having dentures (that is, had a non-missing dentures phenotype); 28,701 were removed for not having European genetic ancestry76; 1,469 were removed for not having available TOPMed-imputed genotypes (including for chromosome X); 2,601 were removed for not having available WGS data; and 53 were removed for having withdrawn, leaving 419,545 available individuals for GWAS. For the binary oral health phenotypes (dentures use and bleeding gums), 418,039 had non-missing values. For the quantitative BMI z-score phenotype77, 418,150 had non-missing values.

TOPMed-imputed variants for these individuals were filtered to require minor allele frequency >0.001 and INFO >0.3. BOLT-LMM was run in linear regression mode on these samples and variants with the following covariates: age, age squared, sex, genotype array, assessment centre and top 20 genetic ancestry PCs. For estimating effect sizes of specific copy numbers of AMY1 (Fig. 3d,e,j), AMY2A (Extended Data Fig. 6f) or AMY2B (Extended Data Fig. 6g), we performed logistic regression (for oral health phenotypes) or linear regression (for BMI) with the same covariates, encoding each copy number (rounded to the nearest integer) as a separate factor and using the modal copy number as the reference level.

Phyletic stratification of genetic associations

The phylogenetic tree of all species in the MetaPhlAn 4 database used (v.Oct22), mpa_vOct22_CHOCOPhlAnSGB_202212.nwk, was first subsetted to the tree spanning nodes with primary label among the 439 species seen at >10% prevalence in the SPARK cohort. This tree was used with graphlan (v.1.1.3) for depiction of phylogenetic trees (Figs. 1b and 2e and Extended Data Fig. 5f). For comparisons among the effect sizes of a human genetic variant associated with relative abundances of many species, phylogenetic distances between pairs of species were first computed as a cophenetic distance matrix from this tree. For a given index species A, phylogenetic distances between A and other species B were then compared with either (1) absolute values of effect sizes for species B (that is, |βB|, Extended Data Fig. 5b,c,g,h) or (2) effect sizes for species B oriented relative to the effect direction for species A (that is, sign(βA) × βB, Extended Data Fig. 5d,e,i,j).

Estimation of AMY1 copy number in all cohorts

In the SPARK (Extended Data Fig. 6a) and AoU v7 cohorts (Extended Data Fig. 6c), AMY1 copy number was estimated by counting WGS reads that mapped to the duplicated regions that include AMY1A (chr. 1: 103638545–103666411), AMY1B (chr. 1: 103685558–103713427) and AMY1C (chr. 1: 103732687–103760549) in GRCh38 and normalizing against the total number of reads that aligned in either the 0.5 Mb upstream of AMY2B or the 0.5 Mb downstream of AMY1C. For the UKB cohort (n = 490,415 (ref. 78), Fig. 3a), we applied a more comprehensive read-depth normalization pipeline that incorporated sample-specific GC-bias correction inferred from genome-wide alignments (similar to Genome STRiP79) before normalizing against read depth in the 0.5 Mb regions flanking the amylase locus. We corrected for slight miscalibration of these diploid copy number estimates by fitting a linear model to identify coefficients that centred peaks of copy number estimates at integers.

Among the UKB participants with WGS available, we identified 5,149 siblings that shared both amylase haplotypes IBD2 (based on at most three mismatching SNP-array genotypes in a 2 Mb window flanking the amylase locus, computed using plink1.9 –genome). Among these IBD2 sibling pairs, 13 pairs were identified as copy number discordant (and likely to reflect a copy number mutation in the past generation) based on (1) having AMY1 copy number estimates that differed by >1.0 and (2) having AMY2A copy number estimates consistent with a duplication or deletion of a commonly variable amylase gene cassette (that is, ±1 AMY2A copies for AMY1 copy number discordances of odd parity and no difference in AMY2A copy number for AMY1 copy number discordances of even parity). We estimated AMY1 copy number genotyping accuracy by computing the correlation across IBD2 sibling pairs excluding these 13 copy number discordant pairs.

Testing AMY1 copy number for association with dental phenotypes and BMI in All of Us

We defined the binary tooth loss phenotype as 1 for individuals with at least one recorded instance of ‘acquired absence of all teeth’ (OMOP concept ID: 40481327, code: 441935006) and 0 otherwise. Likewise, the caries phenotype was derived from ‘dental caries’ (OMOP concept ID: 133228, code: 80967001). For BMI, we generated a normalized z-score phenotype from BMI (OMOP concept ID: 903124, code: bmi) by first adjusting for age (in months, determined from time at weight and height measurement) and age squared and then applying inverse rank normal transformation in each sex separately. The BMI z-scores for males and females were then merged together.

Individuals with WGS available for genotyping AMY1 copy number were first filtered to an unrelated subset of samples (iteratively dropping one individual per related pair with kinship score >0.1, from relatedness_flagged_samples.tsv). For oral health phenotypes, we performed logistic regression against AMY1 copy number including age, age squared, sex and the top 16 genetic ancestry PCs (from ancestry_preds.tsv) as covariates. For BMI, we performed linear regression using only genetic ancestry PCs as covariates as age and sex had already been residualized out. For estimating effect sizes of specific copy numbers of AMY1 (Extended Data Fig. 6d,e and Extended Data Fig. 7f–i), we performed logistic regression (for oral health phenotypes) or linear regression (for BMI) with the same covariates, encoding each copy number (rounded to the nearest integer) as a separate factor and using the modal copy number of 6 as the reference level (that is, computing the effect size of each copy number relative to copy number 6).

Paralogous sequence variation in AMY1

To identify and genotype paralogous sequence variants (PSVs) from UKB WGS data, we used a read-counting approach similar to our previous work80. In brief, reads from each sample that had been aligned to any of the three 27.6 kb regions in GRCh38 corresponding to AMY1A (chr. 1: 103638695–103666261), AMY1B (chr. 1: 103685708–103713277) and AMY1C (chr. 1: 103732837–103760399) were realigned with bwa (v.0.7.17) to the reference sequence of AMY1A after filtering out reads with any of the last four SAM flags (-F 0xF00). Read counts supporting each base at each position were tabulated with htsbox (r345) pileup, filtering alignments <50 bp and base calls with quality score <20. Individuals were called heterozygous for a PSV allele (having at least one copy of AMY1 with each of two alleles) if at least five reads supported the variant allele in that sample and at least five reads did not. PSVs were then filtered to those with heterozygosity >0.002 (resulting in 892 PSVs passing filters). To estimate diploid copy number genotypes for a PSV, we multiplied each individual’s diploid AMY1 copy number by the allelic fraction of the PSV in that individual. In association tests using linear regression with BOLT-LMM, we rounded copy number estimates to integer genotypes.

For follow-up analyses of effect sizes of specific AMY1 F141C and C477R copy number genotypes, we optimized the assignments of integer copy number genotypes based on manual inspection of histograms of allelic depth-derived PSV copy number estimates (Supplementary Fig. 3). Specifically, we assigned copy numbers for each of F141C and C477R using the thresholds [0,0.25) = CN0, [0.25,1.75) = CN1, [1.75,2.7) = CN2, [2.7,3.5) = CN3 and [3.5,5) = CN4. In UKB, F141C had 416,381 (99.2%), 3,124 (0.74%) and 40 (0.0095%) individuals with 0, 1 and 2 copies, respectively, and C477R had 412,450 (98.3%), 6,527 (1.6%), 547 (0.13%), 19 (0.0045%) and 2 (0.0005%) individuals with 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4 copies, respectively. In SPARK, F141C had 12,459 (99.5%) and 60 (0.48%) individuals with 0 and 1 copies, respectively, and C477R had 12,343 (98.6%), 172 (1.4%) and 4 (0.032%) individuals with 0, 1 and 2 copies, respectively. These threshold-based copy numbers of the alternate alleles were used in logistic regression along with copy numbers of the reference alleles (F141 and C477) and covariates as above.

Protein expression of AMY1

Plasmid pCAGEN81 was a gift from C. Cepko (Addgene plasmid no. 11160; http://n2t.net/addgene:11160; RRID Addgene_11160). Codon-optimized sequences encoding reference, F141C and C477R AMY1 alleles were synthesized and ordered as gBlocks from Integrated DNA Technologies for cloning into pCAGEN downstream of the CAG promoter. Clones were screened for sequence errors before plasmid preparation using Plasmid Plus Midi Kit (Qiagen, catalogue no. 12943). Plasmid pUC19 (New England Biolabs, catalogue no. N3041S) was used as a negative control. A total of 15 µg of each plasmid was lipofected into separate 10 cm plates of HEK293T (Takara, catalogue no. 632180) cells at ~70% confluence using 30 µl of Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, catalogue no. L3000015). Authentication of HEK293T was done by morphological match for type and verification of SV40T antigen with PCR assay. Lack of mycoplasma contamination was confirmed by Takara as well as inhouse with MycoAlert Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Lonza, catalogue no. LT07-318). Medium was switched to serum-free after 24 h before collection of both supernatant and lysate at 72 h post-lipofection. A total of 10 ml of supernatant was spun at 1,000g for 10 min to remove cells and debris before the addition of 100 µl of Halt Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (100×, Thermo Scientific, catalogue no. 78438) and 100 µl of EDTA (0.5 M). Cells were washed with ice-cold PBS before the addition of cold 1 ml of RIPA Lysis and Extraction Buffer (Thermo Scientific, catalogue no. 89900) with 10 µl of Halt Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (100×) and 10 µl of EDTA (0.5 M). After sufficient solubilization of the cells had occurred, 1 µl of Benzonase Nuclease (250 U per µl, Milipore, catalogue no. E1014) and 10 µl of MgCl2 (1 M) were added before incubation at 37 °C, 500 rpm for 30 min. Lysate was then spun at 10,000g for 10 min to remove insoluble precipitate. Both supernatant and lysate were stored at −80 °C until further use.

Western blot of AMY1 in cell culture supernatant and lysate

A total of 7.5 µl of supernatant or purified lysate was first run denatured and reduced in a 10% Mini-PROTEAN TGX Precast Protein Gel (Bio-Rad, catalogue no. 4561036) before wet transfer to nitrocellulose membrane (120 V, 2 h). After evaluation of equal loading by Ponceau S Staining Solution (Thermo Scientific, catalogue no. A40000279), the membrane was blocked for 1 h at room temperature with TBS, 0.1% Tween-20 and 5% w/v non-fat dry milk before washing three times for 5 min each with TBS-T (TBS, 0.1% Tween-20). Amylase antibody (G-10, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalogue no. sc-46657, lot no. G0324) was used as the primary antibody at a 1:200 dilution in TBS-T with 5% w/v milk for incubation overnight at 4 °C with rotation. Membrane was washed three times for 5 min each with TBS-T before addition of anti-mouse IgG, HRP-linked antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, catalogue no. 7076, lot no. 39) as secondary at a 1:2,000 dilution in TBS-T with 5% w/v milk for 1 h incubation at room temperature with rotation. Membrane was washed three times for 5 min each with TBS-T before detection with Amersham ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent (Cytiva, catalogue no. RPN2236) (Extended Data Fig. 7a).

Purification of AMY1 reference and F141C protein

Purification of amylase from supernatant was done using glycogen, adapted from refs. 82,83. All following steps were conducted on ice or at 4 °C (rotation and centrifugation). In brief, 10 ml of supernatant was initially concentrated using prewet 15 ml Amicon Ultra Centrifugal Filter, 30 kDa MWCO (Milipore, catalogue no. UFC9030) and put up to a total volume of 900 µl with PBS. A total 600 µl of cold ethanol was added slowly to make 40% ethanol v/v. This was then centrifuged at 10,000g for 10 min to remove any insoluble precipitate. To the supernatant, 75 µl of 0.2 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8), 75 µl of glycogen (20 mg ml−1, Roche, catalogue no. 10901393001) and 100 µl of ethanol were added in that order. This was then incubated for 5 min with end-over-end mixing before centrifugation at 5,000g for 6 min. The glycogen pellets were then washed twice with 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8) containing ethanol (40% v/v) before resuspension in 100 µl of 50 mM MOPS buffer (pH 7, Thermo Scientific, catalogue no. J61821-AK) with 5 mM CaCl2. These were then incubated at 37 °C, 500 rpm for 30 min to allow for glycogen digestion. The above purification procedure was repeated as necessary to arrive at purified amylase as evaluated on 10% Mini-PROTEAN TGX Precast Protein Gel with InstantBlue Coomassie Protein Stain (Abcam, catalogue no. ab119211) (Extended Data Fig. 7b).

Amylase activity assay

Protein was normalized between reference and F141C isoforms by densitometric measurement against linear dilution series (r2 = 0.99 with input). The concentration chosen for the assay was determined by having maximal linear activity over the observation window. For each technical replicate, 10 µl of reference or F141C amylase enzyme diluted in 50 mM MOPS buffer (pH 7), 5 mM CaCl2 and 0.02% w/v BSA (New England Biolabs, catalogue no. B9000) was quickly mixed with 10 µl of BODIPY FL conjugated-starch substrate from EnzChek Ultra Amylase Assay Kit (Invitrogen, catalogue no. E33651) in 50 mM MOPS buffer (pH 7) with 5 mM CaCl2. The reaction was then maintained at 20 °C for 2 h in a Bio-Rad CFX384 Real-Time PCR Detection System with fluorescence reading taken every minute using FAM fluorophore settings with CFX Manager (v.3.1) software. Fluorescence at 30 min relative to initial reading was used as input to a linear model with allele and plate to regress out any run-to-run effects during comparison across technical replicates (Extended Data Fig. 7c).

Bacterial genome reference panel for analysing bacterial gene dosages

To reduce hypothesis testing burden in association analyses of human genetic variants with bacterial gene dosage phenotypes, we restricted analyses to a set of 30 bacterial genomes representing highly abundant species and species whose abundances we had found to associate with human genetic variants. Specifically, we selected 30 bacterial species with genomes available in GenBank by including: (1) the five most abundant species in SPARK oral microbiomes, (2) species that associated strongly (P < 4 × 10−11) with at least one human genetic variant and (3) the top two associated species for each locus if not already included. We substituted Stomatobaculum longum for the related Stomatobaculum SGB5266 which would have been included under (2) but lacked a GenBank assembly. We selected a single genome for each of the 30 species using the following criteria. The SGB centroid was prioritized over other genomes if it corresponded to a GenBank assembly. For cases in which the centroid was not a GenBank assembly and multiple genomes corresponded to GenBank assemblies, the reference genome was prioritized if available, or otherwise the highest ranked genome among those listed. A list of these species and GenBank assemblies is included in Supplementary Table 6. A bowtie2 index was then built from these merged genomes.

Measuring bacterial gene dosages using read-depth phenotypes

We computed WGS coverage-derived phenotypes informative of gene dosage across each of the 30 bacterial reference genomes by first realigning unmapped reads from SPARK saliva WGS to the 30 reference genomes using bowtie2 (v.2.5.1) with the –very-sensitive flag. These alignments were then position-sorted within contigs with samtools (v.1.15.1). For each WGS sample, we quantified read depth in 500 bp bins tiling each of the 30 bacterial reference genomes using mosdepth (v.0.3.6), excluding reads with mapping quality <5. For each sample, for each of the 30 bacterial reference genomes, we then median-normalized the bin-level read-depth measurements across the 500 bp bins of that reference genome to control for species abundance (such that normalized read-depth measurements had a median of 1 among bins corresponding to each species). If a sample had <0.5× median coverage across bins corresponding to a given species, we set that sample’s normalized read-depth measurements for that species to missing to focus downstream analyses on samples with less-noisy measurements. Finally, we truncated median-normalized read-depth values to the interval [0,1], both to focus on deletions in bacterial genomes and to reduce the influence of outlier measurements that might reflect mismapped reads (potentially derived from either duplicated genomic regions or homologous sequences in microbial species not represented among the 30 reference genomes). We reasoned that these bin-level measurements would capture kilobase-scale deletions of bacterial genomes, circumventing the need to predefine a set of structural variant regions (which was difficult because of the limited sequencing coverage of most species). Additional details are provided in Supplementary Note 5.

Testing bacterial gene dosage phenotypes for association with host genotypes

We used linear regression to test each of the 11 human genetic variants we had found to associate with oral microbiome composition (Extended Data Table 1) for association with normalized read depth (truncated to [0,1]) in each 500 bp bin of each of the 30 bacterial reference genomes. We used an additive model for all variants except FUT2 W154X and TLR1 I602S, for which we used a recessive model (corresponding to secretor/non-secretor status for FUT2). We took two precautions to avoid potential confounders. First, for each of the 30 species, we included as covariates the top 20 PCs of the normalized, truncated read-depth matrix for that species (running PCA after centring and scaling each bin to have a mean of 0 and s.d. of 1 across samples) to control for linked gene dosages (for example, differences across strains) that could potentially generate non-causal associations in a manner analogous to population structure in GWAS (Supplementary Note 5). Second, we applied a form of genomic control84 (applied across the 500 bp bins of each reference genome) to adjust for remaining test statistic inflation. Specifically, for each pairing of a species and a human genetic variant, we computed the adjustment factor

$$\frac\rmmedian\,(\chi _1^2)F^-1(0.5)$$

across the \(\chi _1^2\) test statistics for the 500 bp bins of that reference genome, where F−1(x) is the inverse cumulative distribution function for a \(\chi _1^2\) random variable. The \(\chi _1^2\) test statistics were then divided by this factor. This yielded 208 read-depth bins in 18 species that significantly associated with at least one of the 11 human genetic variants (FDR < 0.01, Supplementary Tables 7 and 8) and resolved to 68 unique microbial regions after merging bins within 1.5 kb of another significantly associated bin (Fig. 4b). We verified that the truncated normalized read-depth phenotypes involved in these associations were broadly reasonably distributed (with most bimodal at 0 and 1 and mean between 0.05 and 0.95; Supplementary Table 7), such that testing these phenotypes for association with common variants (MAF = 0.08–0.45) using linear regression in a cohort of size 12,519 was expected to produce robust test statistics77.

For combinatorial analysis of deletions of the five vad genes in V. sp. 3627 that associated in the same direction with FUT2 genotype (vadB through vadF) (Fig. 6e), we first selected individuals whose oral microbiomes had evidence of near-complete presence (>0.8 median-normalized coverage) or near-complete absence (<0.2 median-normalized coverage) of each vad gene (n = 3,081, representing roughly half of the SPARK samples with coverage of the V. sp. 3627 genome reaching the >0.5× threshold for analysis). For each common combination (>2.5% of selected individuals) of presence/absence status of vadB through vadF, the number of individuals with each FUT2 W154X genotype were then counted.

Replication of bacterial gene dosage associations in the All of Us cohort

To evaluate the generalizability of the associations we identified in SPARK between human genetic variants and bacterial gene dosages, we applied the same computational pipeline described above to 10,000 randomly selected saliva-derived WGS samples from the AoU v.8 data release. We then attempted to replicate the 208 associations (between human genetic variants and normalized read-depth measurements in 500 bp bins of bacterial genomes) that had reached significance (FDR < 0.01) in SPARK.

AlphaFold3 prediction of protein structures

To predict protein structures for Streptococcus parasanguinis AbpA or AbpB (bound to human AMY1), the Veillonella sp. 3627 VadD trimer and Streptococcus mitis CrpE, we used AlphaFold3 (ref. 85) for multimer prediction with default reference databases and max template date of 2021-09-29. The TonB domain of AbpB and the signal peptide of VadD were excluded for visualization. To minimize the model size, CrpE was truncated to the region spanning the CshA NR2 domain to the sixth mucin-binding domain (residues 572–2701). Structures were visualized with ChimeraX (v.1.9)86 and pLDDT, pTM and ipTM values can be found in Supplementary Table 9.

Genetically derived blood typing in SPARK

We assigned blood types to SPARK participants on the basis of WGS-derived SNP and indel genotypes using a procedure similar to previous work12. The genotype of the rs8176746 missense SNP was first used to determine an individual’s dosage (that is, allele count) of type B alleles (T allele count) and non-type B dosage (G allele count).

The rs8176719 indel was next used to determine type O1 dosage (deletion allele count), which was subtracted from the non-type B dosage to yield non-type B/O1 dosage, as the rs8176719 deletion allele typically occurs on haplotypes that would otherwise be type A alleles. Although this is true in European, East Asian and American ancestry haplotypes in 1KGP populations, in a small fraction of African (3.2%) and South Asian (0.2%) ancestry haplotypes, the rs8176719 deletion occurs in cis with the type B missense allele. As we found 36 SPARK participants who had O1 dosage exceeding non-type B dosage, we subtracted this excess from their type B dosages.

The rs41302905 missense SNP was next used to determine type O2 dosage (T allele count) and subtracted from the non-type B/O1 dosage to yield type A dosage, as it seems to be in cis with type A alleles in all 1KGP populations. O1 and O2 dosages were then merged to compute type O dosage.

The rs56392308 indel was next used to determine the type A2 dosage (deletion allele count) and subtracted from the type A dosage to yield type A1 dosage. For seven individuals in which the type A2 dosage exceeded type A dosage, five seemed to be on type O alleles and two on either type O or type B alleles, so this excess was subtracted from their type A2 dosage.

Enrichment of conserved domains in bacterial genes associated with secretor status

For each of the bacterial species with adhesin genes in dosage variable regions that associated with FUT2 loss of function (Fig. 6a–c,f,g), protein IDs (WP numbers) for the species were extracted from its RefSeq general feature format (GFF) file. Conserved domains (from National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) conserved domain database) were identified for each protein using a modified version of the provided bwrpsb.pl script (applied to up to 250 proteins at a time). A one-sided Fisher’s exact test was used to identify domains enriched among proteins encoded by genes within read-depth bins that associated with FUT2 genotype.

GWAS of read depth in selected microbial genomic regions

We used BOLT-LMM to perform GWAS on the five normalized read-depth phenotypes for which we observed the most significant associations with human genetic variants (in our targeted analysis of 11 human genetic variants). Specifically, these phenotypes measured WGS read depth in the following 500 bp bins: H. sputorum QEQH01000003.1: 197,000–197,500, P. nanceiensis KB904333.1: 123,500–124,000, S. mitis MUYN01000003.1: 100,000–100,500, S. vestibularis AEKO01000011.1: 186,000–186,500, V. sp. 3627 RQVG01000009.1: 13,500–14,000. In each GWAS, we included as covariates the top 20 PCs of the normalized, truncated read-depth matrix for the species under consideration, along with sequencing batch, age, age squared, square root of age, sex, percentage of mapped reads and the top ten human genetic PCs.

We also used BOLT-LMM to perform GWAS on normalized read-depth measurements in 500 bp bins spanning the genome of R. mucilaginosa (the most prevalent species observed in SPARK). To avoid test statistic inflation due to non-normality, we first excluded bins for which <10% of samples had non-modal read-depth values, leaving 3,441 bins. We then rank-based inverse normal transformed these bins (with random tie-breaking) to further normalize the phenotypes. We ran BOLT-LMM using the same covariates as above.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.