Rationale of EBV detection

The 171,823-nucleotide EBV genome (NC_007605.1) was first included in December 2013 (hg38 version GCA_000001405.15) as a sink for off-target reads that are often present in sequencing libraries, to account for pervasive EBV reads present from the immortalization of LCLs (as with the 1000 Genomes Project and related consortia). Importantly, WGS in the UKB and AOU consortia was performed on whole blood18,60, reflecting that EBV reads detected would derive from viral DNA from past infections.

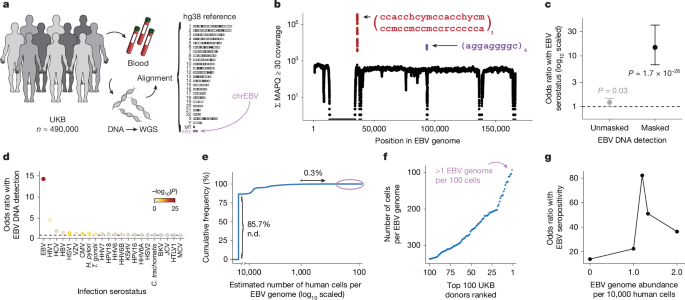

WGS data and cohort analyses in the UKB

For the UKB, we obtained per-base abundance of EBV DNA of the 490,560 WGS libraries by extracting reads aligning to chrEBV in the hg38 human genome reference that had a read mapping quality (MAPQ) ≥ 30 (q30) via the SAMtools view command61. To quantify EBV DNA abundance for each position, we summed the coverage of each base in the EBV genome across all libraries (per-base abundance). The resulting coverage across the viral contig was approximately flat, supporting that EBV DNA detection from WGS reads was real viral DNA, with two key exceptions (Fig. 1b). First, a total of 27,692 positions had low to no coverage (per-base abundance ≤10) due to low mappability of the EBV contig. Second, two regions (positions 36,390–36,514 and 95,997–96,037) had orders-of-magnitude higher coverage (per-base abundance of ≥103 at these 166 positions). On further examination, the sequences were highly repetitive. Hence, we reasoned that these two regions may confound EBV DNA quantification. To assess this, we calculated EBV DNA abundance per person before and after masking, by summing MAPQ ≥ 30 coverage either across all J = 171,823 bases, or only across the remaining J′ = 143,965 well-covered bases (10 < per-base abundance < 103 for each base). The per-individual EBV sum unmasked was computed over all J bases, whereas the masking was performed over J′ bases.

We then used a two-sided Fisher’s exact test to test for association between EBV DNA presence (EBV DNA coverage > 0) and EBV serostatus, recorded in the UKB as ‘EBV seropositivity for Epstein–Barr Virus’ (data field 23053). Before masking, EBV DNA presence had a weak but insignificant positive association with EBV seropositivity (odds ratio = 1.2, P = 0.03). Conversely, after masking these repetitive regions and recomputing donor detection status, the association between EBV DNA detection and seropositivity was much stronger (odds ratio = 14.6, P = 1.7 × 10−26) (Fig. 1c). These analyses demonstrate that masking highly repetitive regions in the viral contig is required to perform valid inferences from whole genome sequencing data, as evidenced by statistical overlap with EBV serostatus.

Contig mappability analyses

To confirm that regions of the EBV contig that were not detected were attributable to poor mapping quality of those regions, we generated synthetic reads of length 101 bases by tiling the reference EBV contig. Next, each synthetic read was aligned using bowtie2 v.2.5.1 (ref. 62). We define mappability as the percentage of reads overlapping a position with a map quality score exceeding ten. This analysis reproduced regions depleted from the pseudobulk abundance (Extended Data Fig. 1a), indicating that low detection in these regions was due to homology in the hg38 reference rather than variable DNA presence from past infection.

EBV DNA copy number estimation, simulation and thresholding

To calculate EBV DNA abundance per person, we summed the coverage over the well-covered, non-biased bases (J′). We normalized this value against the effective EBV genome size (143,965 bases) to obtain an estimate of the coverage per EBV genome. Next, we used the 30× human WGS coverage and accounted for the diploid human genome to compute an estimate of EBV DNA copy number per human cell, which resulted in approximately 1 in 1,000–10,000 cells in individuals with detectable EBV DNA (that is, our limit of detection was approximately 1 EBV genome per 10,000 cells). To contextualize these values, the upper range of EBV copy numbers in healthy individuals measured using qPCR was 103 EBV genomes per 1 µg DNA, or 1 EBV genome per 200 cells23. The latter number was estimated with the assumption that 105 cells produce 0.5 µg DNA. Although a previous study similarly used EBV reads in a cohort of ~8,000 donors, this analysis did not correct for the repetitive, biased DNA abundances that significantly skewed the resulting quantification4. After quantifying per-person EBV DNA abundance, 85.7% of individuals in the UKB had no detectable EBV DNA.

In the UKB cohort, over 90% of individuals are seropositive, yet only 14.3% of individuals have non-zero EBV DNA levels detected. Therefore, we conducted a simulation study to better characterize the discrepancy. Using maximum likelihood estimation, we estimated values for the mean and standard deviation of a log-normal distribution to initialize the simulation and subsequently modified these values to (1) account for a mixture including 10% zeros (representing the individuals who were not infected with EBV) and (2) adjust the mean for a round, interpretable number. The final values used in the simulation (Extended Data Fig. 1d) were set to zero for 50,000 individuals, whereas the remaining 450,000 individuals were simulated via a log-normal distribution, with a mean of 0.2 EBV genome copies per 10,000 cells, a standard deviation of 0.62 and a censored value of 0.71. We emphasize that this simulation does not test an explicit statistical question but is designed primarily for illustrative purposes, to show that a single underlying component can explain many features of the empirical data (rather than requiring a second condition).

The extreme skew of the EBV levels distribution (Extended Data Fig. 1f) motivated our transformation of EBV DNA copy number to a binary trait, which we define as EBV DNAemia, since a quantitative trait otherwise assumes a dose-dependent relationship when testing for associations. To binarize our data for downstream analyses, we used a series of two-sided Fisher’s exact test to survey different cutoffs against association with EBV serostatus (Fig. 1g). Our goal was to determine an optimal EBV copy number threshold. We observed the most significant positive association with a threshold of 1.2 EBV copies per 104 human cells (odds ratio = 82.17, P ≈ 0) after accounting for standard covariates used in a GWAS analysis (age, sex, age × sex, and ancestry PCs 1–15). This corresponded to having a per-person abundance of at least 302 bases covered on the EBV genome, which in turn corresponded to a full paired-end sequencing read (2 × 151 bp) with no soft-clipping. There were 47,452 people (9.67%) with EBV copy numbers greater than this threshold, which was used for all downstream analyses.

For the 9,607 individuals with both EBV serology and WGS available, there were 919 individuals (9.57%) that had EBV DNAemia. Only two (0.2%) of these 919 individuals were seronegative. One donor had an EBV DNA load of 1.36 EBV genomes per 104 cells (just above our EBV DNAemia cutoff) with a high VCAp18 titre, but low titres for the other three EBV antigens. The other donor had an EBV DNA load of 3.34 EBV genomes per 104 cells, with a positive titre for EA-D but low titres for the other antigens. In other words, among the 347 donors with no seropositivity against any antigens, none were annotated as individuals with EBV DNAemia (Extended Data Fig. 1b).

EBV DNA detection in AOU

We obtained per-base abundance of EBV DNA for 245,394 people in AOU with WGS data similarly by extracting reads that mapped to chrEBV in the hg38 human genome reference with MAPQ ≥ 30. To quantify EBV DNA abundance per base, we summed the q30 coverage of each base in the 171,823 bp EBV genome across all people. We again observed an overall uniform coverage; 23,513 positions had no coverage (per-base abundance = 0), and four regions (positions 36,389–36,516; 52,012–52,034; 95,997–96,037 and 163,596–163,617) had abnormally high coverage (per-base abundance of >1,000 at 214 positions; Extended Data Fig. 2b). The effective EBV genome size was the remaining 148,096 bases (>0 but <103 for each base). Although the largest repetitive region was the same in both the UKB and AOU, differences in the other regions with variable bias could be attributed to differences in the alignment software for either cohort, noting that all analyses used the existing mappings from either cohort.

We quantified the EBV copy number per person in AOU with a similar approach to the one used for the UKB. In brief, we quantified EBV DNA loads after masking and normalized them by the effective EBV genome size, then by the average genome coverage (30× human WGS) provided by AOU metadata. A total of 51,459 people (21%) had detectable EBV DNA (Extended Data Fig. 2c). The top EBV DNA load harboured was ~1 EBV copy per 1.4 cells (or 7,046 EBV copies per 104 cells).

Using the same EBV DNA copy number thresholds as in the UKB, a total of 29,249 people (11.9%) had EBV copy numbers greater than the threshold of 1.2 EBV copies per 104 human cells (Extended Data Fig. 2c). The overall higher EBV loads in AOU compared to in the UKB may be due to a difference in the recruitment criteria and demographics of the two cohorts: relative to the general population (as in AOU), the UKB shows a ‘healthy volunteer bias’ where participants were less likely to have self-reported health conditions57. In comparison, the maximum copy number described in a previous paper was a few orders of magnitude higher (2,404,531 EBV copies per 105 human cells), potentially due to our exclusion of abnormally high coverage regions4.

Phenome-wide association studies

We conducted PheWAS using the UKB as a discovery cohort to test for the association between EBV DNAemia and 13,290 binary phenotypes and 1,931 quantitative phenotypes amongst participants with broadly NFE as in the GWAS (refer to the following section). We used logistic regression with Firth correction, including sex and age as covariates. Using a Bonferroni correction, we defined 0.05/15,221 = 3.3 × 10−6 as our significance threshold. To ensure that the PheWAS was not confounded by immunosuppressive drugs, we ran a secondary analysis in which we included immunosuppressive drug status as an additional covariate in the regression. Because a majority of blood samples used for WGS were drawn at the time of enrollment, we identified these individuals on the basis of medication taken at the time of their initial assessment visit (UKB data field 20003). A full list of the 169 medications used for annotating immunosuppressed individuals is reported in Supplementary Table 2.

As validation in AOU, we obtained unique RxNorm codes for 53 of the 169 drugs (Supplementary Table 2) and queried for individuals that had any of these drug exposures, along with the exposure start and end dates. We annotated each individual as immunosuppressed only when the biosample collection date for WGS fell between the drug exposure start and end dates (or after start dates, if no end date was recorded). We observed a positive but not significant association between immunosuppressive drug exposure at the time of WGS collection and EBV DNAemia (odds ratio = 1.03, P = 0.54) (Extended Data Fig. 2f).

We replicated PheWAS associations using the AOU cohort of individuals with European ancestry via Fisher’s exact tests for association between EBV DNAemia and each representative ICD-9 or ICD-10CM code in AOU. As recommended in the AOU workbench, we defined a representative ICD code as a code appearing at least twice in a person and 20 instances across all participants. The top results were predominantly being HIV positive, having immunodeficiencies, or receiving organ transplants, which we also observed in the UKB. To compare effect sizes between hits in the UKB and AOU, we matched AOU ICD-10CM codes to a corresponding UKB ICD-10 code by taking the first four characters of the ICD-10CM code, as codes >4 characters do not exist in the ICD-10 ontology used in UKB. For the two traits linked to EBV discussed in the main text, multiple sclerosis was queried using the ICD-10CM code ‘G35’ in AOU, and gammaherpesviral mononucleosis was queried using the ICD-10CM code ‘B27.00’.

Genetic associations with EBV DNAemia in the UKB

For UKB individuals of broadly NFE ancestry, array-based imputed genotypes with good genome-wide coverage in the common (>5%) and low-frequency (1–5%) MAF ranges were available17. Genotyping arrays capture genome-wide genetic variations (SNPs and indels) within both coding and noncoding regions, allowing imputation of genotypes and tests for association between genotypes and a specified trait. To avoid confounding results due to differences in ancestral background, we stratified the cohort across six broad genetic ancestries (African, AFR; Hispanic or Latin American, AMR; Ashkenazi Jewish, ASJ; East Asian, EAS; non-Finnish European, NFE; and South Asian, SAS) before testing for associations between EBV DNAemia and UKB-imputed genotypes, which resulted in a total of 450,032 individuals with array imputed genotype data available, including 426,563 individuals of NFE ancestry. We then used REGENIE v.3.5 (ref. 63) to examine associations between EBV DNAemia and imputed genotypes, using a logistic model with covariates and applying Firth correction: EBV DNAemia ~ age + sex + age × sex + age2 + age2 × sex + batch + ancestry PCs 1–20, as previously described64. The input to REGENIE includes directly genotyped variants (MAF > 1%, MAC > 100, genotyping rate per variant >99%, and genotyping rate per individual >80%). We pruned these variant sets using PLINK2 (–indep-pairwise 1000 100 0.8) as input to REGENIE’s step1 analyses. This step produces a whole genome regression model to fit to the binary trait of EBV DNAemia and outputs a set of genomic predictions.

For REGENIE step2, we further filtered out SNPs that had 0.99 ‘missingness’, imputation INFO < 0.7, and p.HWE > 1 × 10−5. This step fits a logistic model to imputed data, using the genomic predictions from step1. To estimate heritability of SNPs and genomic inflation, we performed linkage disequilibrium score regression (LDSC) by applying the ldsc package (v.1.0.1). In brief, we used munge_stats.py on the cleaned summary stats, then used ldsc.py to estimate h2 using the supplied 1KG Genomes linkage disequilibrium score matrices (Supplementary Note 4). Identical steps were applied to conduct the EBV serology GWAS on the subset of UKB participants for whom EBV serostatus was measured40.

To annotate variant loci, we focused on significant variants (P < 5 × 10−8) and created genomic intervals of ±1 Mb around each variant. As variants on chromosome 6 often exhibit linkage disequilibrium with MHC, we created a custom interval (chr6: 25,500,000 to 34,000,000) for the HLA region. We then combined overlapping intervals using the GenomicRanges reduce function and selected the most significant variant per interval as the index variant. In the case of ties, we selected the variant closest to the midpoint of the region. We applied the reduce function again to ensure we had a set of non-redundant index variants. Finally, we annotated each variant by the closest gene, using Ensembl v.111 (Jan 2024) gene annotations and selecting the gene whose midpoint was closest to the index variant. For visualization of specific loci, we used the canonical hg38 reference genome isoforms. Linkage disequilibrium was determined via LDlink65 for the regions noted (Supplementary Note 4). Zoom plots were from the array-based GWAS associations in the UKB, and the linkage disequilibrium reference panel in LDLink65 used all European populations.

We complemented our GWAS with an exome-wide association analyses (ExWAS), leveraging the whole genome sequencing data available in the UKB. Specifically, we tested for associations between EBV DNAemia and protein-coding variants observed in at least six participants of NFE ancestry in the UKB. We applied our previously described protocol to generate variant-level statistics29,66. Variants were required to pass the following quality control criteria: coverage ≥10x; ≥0.20 of reads with the alternate allele for heterozygous genotype calls; binomial test of alternate allele proportion departure from 50% in heterozygous state P ≥ 1 × 10−6; GQ ≥ 20; Fisher Strand Bias ≤ 200 for indels and ≤ 60 for SNVs; root-mean-square mapping quality (MQ) ≥ 40; QUAL ≥ 30; read position rank sum score (RPRS) ≥ −2; mapping quality rank score (MQRS) ≥ −8; DRAGEN variant status = PASS; and ≤ 10% of the cohort with missing genotypes. Additional out-of-sample quality control filters were also imposed based on the gnomAD v2.1.1 exomes (GRCh38 liftover) dataset67. The sites of all variants were required to have ≥10x coverage in ≥30% of gnomAD exomes and, if present, each variant was required to have an allele count ≥50% of the raw allele count. Variants with missing values for any filter were retained unless they failed another metric. Variants failing quality control in >20,000 people were also removed. P values were generated via Fisher’s exact two-sided test. Three distinct genetic models were studied for binary traits: allelic (A versus B allele), dominant (AA + AB versus BB), and recessive (AA versus AB + BB), where A denotes the alternative allele and B denotes the reference allele. ExWAS hits were filtered following: P < 5 × 10−8, nCases >20, and protein-altering Most Damaging Effect (‘Stop_lost’, ‘Stop_gained’, ‘Start_lost’, ‘Splice_region_variant’, ‘Splice_donor_variant’, ‘Splice acceptor variant’, ‘Missense_variant’, ‘Frameshift_variant’, ‘Disruptive_inframe_insertion’,‘Disruptive_inframe_deletion’). For functional variant annotation and interpretation, AlphaMissense68 was executed on all variants that were statistically significant from the ExWAS analyses using default parameters. If multiple transcripts were associated, only one is reported (the one with the highest AlphaMissense score, if available).

Replication of UKB EBV DNAemia-associated genotypes

To broadly capture variants in individuals with EUR ancestry in AOU, we used the variant-level metadata for the SNP and indel variants contained in the short read WGS (srWGS) data dictionary. We filtered for variants with an alternative allele frequency (AF) of 0.01 < AF < 0.49 or 0.51 < AF < 0.99 (gvs_eur_af) and at least 100 individuals containing this variant (gvs_eur_sc ≥ 100) in the EUR subpopulation as the input SNPlists to step1 and 2 of the REGENIEv3.2.4 pipeline. This resulted in 16,566,413 variants across chromosomes 1–22. EBV DNAemia was supplied as a binary trait, along with the covariates age, sex, age × sex, and ancestry PCs 1–15. There were 133,578 such individuals that had EBV DNAemia status determined, of which 131,938 had complete covariate data and were included in the analysis, and 12,099,305 total variants had GWAS statistics results.

Genomic architecture associations

To holistically evaluate genetic architecture similarities between EBV DNAemia and IMDs, we used the R package cupcake38. The package was used to define shared components of genetic architecture across 13 IMDs, applying shrinkage to adjust for linkage disequilibrium, allele frequency and differential sample size. Summary statistics of 13 large IMD GWASs were used to define a reduced dimension space using PCA, which served as a common genetic basis that enabled simultaneous comparisons between multiple diseases. The reduced dimension space included 566 driver variants and 13 PCs that were defined as orthogonal genetic risk components38. Applying this approach, we extracted summary association statistics for these 566 driver variants from our UKB NFE EBV DNAemia GWAS. After checking and adjusting the effect allele alignment, we used cupcake38 to project these variants onto the 13 IMD genetic risk bases and assess the significance of association with each component. The output from this projection is a score or delta (δ) for each PC that quantifies the difference between the projected genetic risk for that trait on a particular basis axis and a synthetic control (which has zero effect sizes for all SNPs). This effectively measures how strongly the trait aligns with the risk architecture represented by that component. To account for uncertainty, the variance of δ is calculated using the propagation of error from the input GWAS summary statistics, adjusted for the same shrinkage weights and allele frequency variance as applied in basis construction. With δ and its variance, a Z-statistic can be formed for each component, and standard statistical inference can be used to compute a P value38.

Pathway and single-cell analyses

To evaluate the gene expression program uncovered by our ExWAS associations, we used a high-resolution single-cell cellular indexing of transcriptomes and epitopes by sequencing (CITE-seq) dataset of PBMCs from eight distinct donors with 210,911 quality-controlled cells41. The 148 ExWAS-associated genes were input alongside the preprocessed Seurat41 object into the AddModuleScore function with default hyperparameters. To reduce technical variation, we removed genes mapping to the HLA region as well as ribosome-associated genes from the input gene list (HLA for genetic polymorphisms; ribosome for cell quality) from the module score foreground and background. Downstream association analyses of cell type enrichment were performed using the pre-supplied labels.

Pathway enrichment analyses were performed using the same ExWAS gene set via the clusterProfiler R package69. Gene set analyses were performed using the enrichGO (for biological processes) and enrichKEGG functions (for pathways) using the set of 148 genes and all ENSEMBL human genes as a background set. For analyses with HLA (Fig. 4e) and chromosome 6 excluded (Fig. 4f), we removed either HLA or chromosome 6 genes from both the foreground (that is, test set) and background set for statistical analyses. We used the simplify() function in clusterProfiler with a similarity cutoff of 0.7 (the default value) to reduce the number of redundant association terms. Hence, we note that the labels in panels Fig. 4d–f are not identical in name; this result is due to the simplify() function’s selection of a single term that is nearly identical to other related terms.

Enrichment analyses for non-coding enrichment in accessible chromatin used 18 fluorescent activated cell sorting (FACS)-isolated immune and hematopoietic populations that were uniformly reprocessed and aggregated using the hg19 reference genome (Extended Data Fig. 5a). To compute enrichment scores, we isolated genome-wide significant variants from the UKB NFE GWAS, lifted over the hg38 coordinates to hg19, and built a RangedSummarizedExperiment object to compute the enrichment. For accessible chromatin enrichments, we used an approach motivated by the chromVAR statistical testing framework adapted for genetic variants. Specifically, 100 background peaks (identified through the same mean and GC content of the ATAC-seq peak) were used as a null distribution, and the mean deviations at peaks variably containing genome-wide significant variants were computed via the abundance of accessible chromatin from each sorted population. The background and observed deviations were used to estimate an empirical Z-statistic, which was transformed into a P-value using the pnorm() R function.

HLA haplotype and EBV peptide presentation

We used the four-digit HLA imputation calls processed in the UKB Research Analysis Platform using HLA*IMP:02 (ref. 70). Allele dosage values of >0.7 were used to assign donor haplotypes for a specific four-digit HLA allele. Homozygotes were determined by alleles with values of >1.3. For the AOU cohort, predetermined HLA genotypes were not available in the workbench. Hence, we reconstructed the HLA calls for all individuals of EUR ancestry using the T1K toolkit71 (v.1.0.8-r237) by extracting reads aligning to the HLA region, which included canonical chr6 HLA region (chr6: 25,500,000 to 34,000,000) and all alternative HLA contigs in the hg38 reference. Using a .bed file of the HLA region coordinates, these alignments were streamed with the GATK PrintReads commands into the T1K genotyper, which was set to default parameters. Following T1K toolkit recommendations, the donor haplotypes were assigned for alleles called with a quality score of >0. Homozygotes were determined by donors with only a single allele and with a quality score of >30.

To determine specific HLA associations with EBV DNAemia, we used the per-person four-digit HLA alleles for both class I and II as predictors in a logistic regression, with EBV DNAemia as an outcome. Models included standard covariates used throughout the paper (age, sex, genetic PCs and so on). We performed this regression on the 208 HLA class I and 145 HLA class II alleles in UKB NFE individuals. We then repeated the same analysis for 175 class I and 132 class II alleles that were also present in the AOU EUR cohort (Supplementary Table 7).

The amino acid sequences of all 87 unique EBV protein sequences were obtained from the peptide sequence of the nuccore NC_007605. The protein .fasta file was input to NetMHCpan, along with all observed MHC class I (HLA-A, HLA-B or HLA-C) and class II (HLA-DR, HLA-DP or HLA-DQ) alleles in the UKB NFE cohort. Sliding windows of all 8-, 9-, 10- or 11-mers of the provided protein sequences were generated for the prediction of class I allele peptide presentation; sliding windows of size 15-mers were used for class II. The binding scores of these peptides were determined for all observed UKB NFE MHC alleles that could be scored by NetMHCpan4.1 and NetMHCIIpan4.3 (ref. 48).

The NetMHC output reflects the predicted %rank score for each peptide and a given allele, which is a measure of the rank of the predicted affinity of the allele for the peptide compared to a set of 400,000 random natural peptides. For MHC class I, we computed the HBR score per allele by taking the harmonic mean over the two genotyped alleles for each of HLA-A, B and C. For homozygotes, the harmonic mean is equivalent to any individual observation. For individuals missing a single allele, we considered only the genotyped call, and for two missing alleles, the individual was excluded from the per-allele analysis.

For MHC class II analyses, all HLA-DRB alleles were directly applied as input—along with the EBV proteome .fasta file—to generate HLA-peptide presentation scores for all possible 15-mer sliding windows. As HLA-DQ and HLA-DR alleles exist in pairs of alpha and beta alleles within the predictions, we took all HLA-DQ and HLA-DP alleles imputed in the UKB NFE cohort and generated all possible combinations of HLA-DQA/HLA-DQB alleles and all possible combinations of HLA-DPA–HLA-DPB allele pairs. These alpha–beta allele combinations were then used as inputs to NetMHCIIpan, along with the EBV proteome .fasta file. Again, the output file lists each peptide, the protein from which the peptide is derived, a given class II allele (pair) and the predicted %rank_EL score, which is the percentile rank of the eluted ligand prediction score. As HLA-DRA is the only non-variable gene in the population, each individual has only two possible HLA-DR heterodimers. Each individual can form four possible alpha–beta heterodimers from HLA-DP and HLA-DQ (between alpha and beta molecules). Hence, each individual may assemble up to ten unique heterodimeric MHC class II molecules50.

The per-allele HBR was computed using the harmonic rank of the heterodimers for each allele class and rescaled by a factor of 106 when computing the final ∆HBR score (shown in Fig. 5). The comparisons were only between the NFE/EUR ancestry populations in either cohort. To further verify that our effect was linked to class II presentation strength, we completed regression analyses using the same set of covariates for our genetic association analyses, which verified that other forms of confounding (for example, population stratification or sex) did not explain the associations between the class II predicted presentation strength and EBV DNAemia.

EBV viral sequence analysis

Raw sequencing reads from chrEBV were merged from all participants from both cohorts. The aggregated .bam file was transformed into a per-base, per-nucleotide count using bam-readcount72. For the type 1 and 2 strain analyses, we sought to quantify the abundance directly from the aligned reads to the chrEBV reference (a type 1 EBV strain). Here we performed a multiple-sequence alignment of the EBNA-2 gene (the major difference between strains) for nuccore IDs K03333 (type 1) and K03332 (type 2) and mapped the MSA coordinates back to the chrEBV reference to identify putative regions that would reflect single nucleotide variation, which, in turn, would reflect strain-level differences. We identified nine variants on chrEBV: 36209C>T, 36226T>A, 36251A>G, 36252A>T, 36258C>A, 36275G>T, 36302A>C, 36312T>A and 36320C>T, where the reference allele was type 1-derived and the alternate was type 2-derived. These variants were selected on the basis of: (1) the combined allele frequency being greater than 99% for the reference and alternate alleles and (2) no overlap with the repetitive regions (Fig. 1b).

Next, we analysed a set of 31 protein-altering mutations in EBV (Extended Data Fig. 7c), which was curated from a recent global-scale analyses of EBV genomes55 derived from individuals with EBV+ nasopharyngeal carcinomas. Of these 31 EBV VUS, there were four VUS that were detected at less than 5% pseudobulk in both cohorts. To assess whether these four VUS were potentially involved in immune evasion, we assembled all possible peptides for presentation on both classes I and II, and then scored these peptides with all of the NFE/EUR observed HLA alleles to compute a NetMHC rank score for both the wild-type and mutated forms of the peptides. As both the wild-type and mutated peptides generally had similar values, and few were near the IEDB-validated thresholds (blue dotted lines; Extended Data Fig. 7d,e), we suggest that these VUS—if there is an effect—are probably not mediated via immune evasion but instead via altered function of the viral protein.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.