Subjects

Male and female mice of C57BL/6J background (Jackson Laboratories, strain 000664) were used in approximately equal numbers for all experiments. Wild-type mice were crossed with DAT:IRES–Cre mice (Jackson Laboratory, strain 006660) or ChAT:IRES–Cre mice (Jackson Laboratory, strain 006410). For slice electrophysiology experiments, ChAT:IRES–Cre mice were crossed with DAT–Flp mice (Jackson Laboratories, strain 035436). All transgenic animals used in experiments were genotyped and found to be heterozygous for Cre-recombinase or Flp-recombinase. Mice were separated by sex and group housed after weaning before surgical procedures or behavioural assays. All behavioural experiments were conducted during the dark cycle (12 h light–dark) when mice were 10–24 weeks old. Mice were housed at approximately 21 °C in 30–70% humidity, and they were food restricted to 85% of ad libitum body weight for all behavioural experiments to facilitate motivated behaviour. All procedures complied with the animal care standards set forth by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and were approved by the Stanford University Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care.

Behavioural training

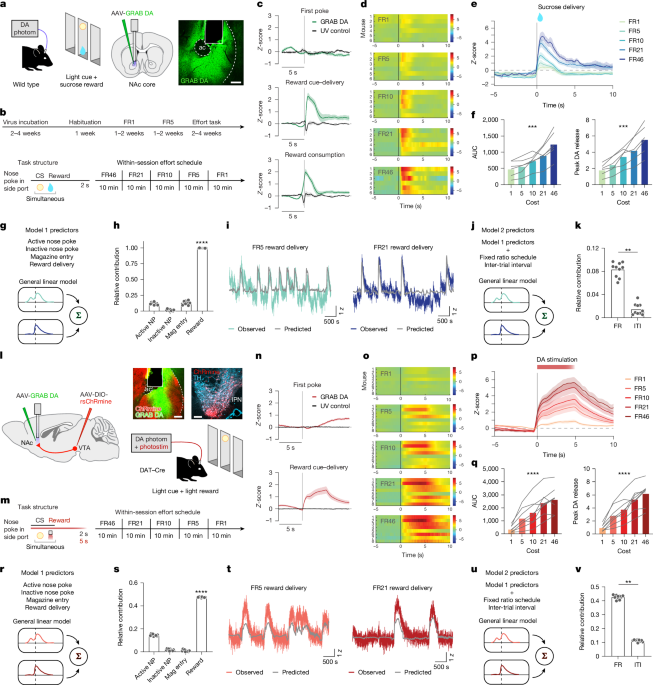

Food restriction and behavioural training began at a minimum of 2 weeks after virus injection and fibre implantation. Before starting behavioural experiments, mice were habituated for 2 days, including handling, tethering to the patch cords and allowing exploration of the operant boxes (Med Associates) for 30 min. After habituation, mice were exposed to 1 day of a Pavlovian task in which rewards were delivered at random intervals spanning 25–35 s for 30 min. Operant chambers were equipped with a speaker for white noise and three identical nose-poke ports, each with an associated cue light and an infrared emitter sensor to measure port entry times. Rewards were delivered in conjunction with a 2-s cue comprising white noise and central port light so that mice would associate reward delivery with the light–sound cue. For sucrose rewards, 10 µl of 32% (w/v) sucrose was used, apart from one experiment in which 5% sucrose was used (Extended Data Fig. 9n–w). After 1 day of Pavlovian training, mice progressed to the operant task. Mice trained on FR1 for a minimum of five sessions. The active nose-poke port (left or right) was counterbalanced between mice; each mouse continued with the same active port for all experiments. On days 1–3, the active food port was baited with a crushed portion of fruit loop to encourage exploration of that port. After earning at least 10 rewards at FR1, with an accuracy (% active nose pokes) of more than 80%, mice progressed to FR5. Mice continued FR5 for at least five sessions and until the number of rewards earned per session remained within 20% for 3 consecutive days. Once this criterion was met, mice progressed to the sucrose effort task. We did not attempt to equalize reward consumption between mice, but rather aimed to ensure that all mice had accurate and internally consistent performance. Training for optogenetic self-stimulation was achieved in the same manner as for sucrose, except the sucrose reward was replaced with 5-s optogenetic stimulation paired with the 2-s light and white-noise cue. All behavioural tasks were coded in Med-PC V (Med Associates).

Sucrose effort task

The sucrose effort task comprised five 10-min blocks of FRs including FR46, FR21, FR10, FR5 and FR1. After mice poked in the active port for the required number of times, sucrose reward (10 µl 32% (w/v)) was delivered in a central magazine, accompanied by a 2-s light and white-noise cue. Once the cue stopped and mice entered the magazine to consume the reward, they were free to start the next trial at their own pace by poking in the active port. As in our previous work17, the FRs were presented in descending order to prevent mice from achieving early satiety under low-cost conditions, except for one control experiment with ascending presentation of blocks (Extended Data Fig. 9j–m). Block transitions were not signalled to the mice.

Modified sucrose effort task

For microinjection experiments with PBS or DHβE, due to concern that the behavioural effect of the drug was a result of the drug wearing off over the course of the session, we used a modified sucrose effort task. In the modified task, after PBS or DHβE injection, mice underwent a 30-min session in which the poking requirement was kept constant for the entire session at either FR1 or FR21. The order of the 4 experimental days (PBS versus DHβE; FR1 versus FR21) was counterbalanced between mice.

ChRmine effort task

The ChRmine effort task was structured identically to the sucrose effort task, except that mice worked for optogenetic DA stimulation. ChRmine stimulation was paired with the same 2-s light and white-noise cue in the magazine port, and upon cue cessation, the mice were free to start the next trial at their own pace.

Stereotaxic injections and viruses

Mice (8–12 weeks old) were anaesthetized with isoflurane (5% induction, 1–2% maintenance). Subjects were fixed on a stereotaxic frame (Kopf Instruments), a small incision was made and burr holes were drilled in the skull over the sites of injection or fibre implantation. The following coordinates relative to bregma were used: VTA, −3.1 mm anteroposterior, ±0.4 mm mediolateral and 4.2 mm dorsoventral; NAc core, 1.5 mm anteroposterior, ±0.9 mm mediolateral and 4.1 mm dorsoventral from the skull surface. Microliter syringes (Hamilton) were lowered to the specified depth from the skull and used to inject 500 nl of virus solution at a flow rate of 0.1–0.25 ml min−1. Borosilicate optic fibres for photometry and/or optogenetic stimulation with 200–400 µm diameter and numerical aperture 0.66 (Doric) were implanted directly above the striatal or midbrain virus injection site and secured to the skull using screws (Antrin Miniature Specialties) and light-cured dental adhesive cement (DenMat, Geristore A&B paste). For the cohorts with recordings in the NAc and cannula or optogenetic fibre placement in the midbrain (Fig. 2 and Extended Data Figs. 3–5), the VTA implant was cemented first and then the NAc fibre was implanted in the same hemisphere. For cohorts with drug microinjections and recordings, a dual optical fibre–cannula (multiple fluid injection cannula, 400 µm diameter, 0.66 numerical aperture; OmFC, Doric) was implanted in the NAc or midbrain. Cannulas for drug microinfusion were implanted 1.5 mm above the target site with the injector extending to the site. For all cohorts, the hemisphere targeted for recordings was counterbalanced between mice.

The adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) used for stereotaxic injections were AAV9-hSyn-GRABDA DA2m (DA4.4, WZ Biosciences), red-shifted AAV9-hSyn-GRABDA rDA2m (WZ Biosciences), AAV2/9-hSyn-gACh4m (GRAB ACh, brain VTA), AAV5-hSyn1-SIO-stGtACR2-FusionRed (Addgene), AAV9-syn-FLEX-jGCaMP8m-WPRE (Addgene), AAV-8-EF1a-DIO-rsChRmine-oScarlet-WPRE (Stanford Gene Vector and Virus Core), AAV-dj-CMV-DIO-eGFP-2A-TetTox (Stanford Gene Vector and Virus Core), AAV-dj-CMV-DIO-eGFP (Stanford Gene Vector and Virus Core), AAV-dj-Ef1a-DIO-NpHR3.0-mCherry (Stanford Gene Vector and Virus Core), AAV-dj-Ef1a-DIO-mCherry (Stanford Gene Vector and Virus Core) and AAV-dj-Ef1a-fDIO-eYFP (Stanford Gene Vector and Virus Core). AAV titres ranged from 1 × 1012 to 2 × 1013 gc ml−1.

Fibre photometry

Mice implanted with optical implants (400 µm diameter, 0.66 numerical aperture, Doric lenses) were connected via a ceramic sleeve (Precision Fiber Products) to low-autofluorescence patch cords of matching diameter and numerical aperture (Doric). Signals passed through a fibre optic rotary joint (Doric) before filtering through a fluorescence mini cube (Doric) and reaching a femtowatt photodetector (2151, Newport). For triple recordings (Fig. 2a–f), the signals from the VTA and NAc fibres were passed through different mini cubes to different photodetectors, thus ensuring full separation between the cell body and axon GCaMP recordings. LEDs (Doric) emitted frequency-modulated ultraviolet (405 nm) and blue (465 nm) light to stimulate control and either GRAB or GCaMP signals through the same fibre. Blue LED power was adjusted to approximately 35 µW at the fibre tip and lowered as needed if the signal saturated the photodetector. Ultraviolet LED power was adjusted to approximately 10 µW at the fibre tip. Digital signals were sampled at 1.0173 kHz, demodulated, lock-in amplified and recorded by a real-time signal processor (RZ5P, Tucker-Davis Technologies) using Synapse software (Tucker-Davis Technologies). Synchronized behavioural events from the Med Associates boxes were collected directly into the RZ5P digital input ports. To reduce any confounds from photobleaching, animals were recorded for about 5 min before behavioural testing began.

Optogenetic manipulations

Optogenetic manipulations with rsChRmine and NpHR were conducted simultaneously as fibre photometry recordings through the same optical implants. Optogenetic manipulation with stGtACR was conducted through optical implants of 200 µm with 0.66 numerical aperture without simultaneous fibre photometry recording. Optogenetic manipulation with rsChRmine or NpHR was conducted by connecting a 625-nm LED light source (Prizmatix) via a plastic fibre (1 mm diameter, NA 0.63) and a fibre optic rotary joint (Doric). rsChRmine stimulation was performed at a stimulation of 5 s, 20 Hz and 6 mW with a pulse width of 10 ms. Optogenetic inhibition with NpHR or control mCherry was conducted with a constant 4 s, approximately 6-mW light. Optogenetic manipulation with stGtACR2 was conducted with a 450-nm LED light source (Prizmatix), using 5–10 s of constant approximately 10-mW light.

Drug administration

For systemic injection experiments, mice were administered intraperitoneal injections of aprepitant 10 mg kg−1 (Axon Medchem), DPCPX 2 mg kg−1 (Tocris), istradeffyline 2 mg kg−1 (Tocris) or SR 48692 5 mg kg−1 (Tocris). DPCPX and instradeffyline were dissolved in DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich) and diluted to 20% DMSO in 0.9% saline to prevent precipitation. Aprepitant and SR 48692 were dissolved in DMSO and diluted to 5% DMSO in corn oil (Sigma-Aldrich) to prevent precipitation. Mice were injected with a volume of 10 ml kg−1. After injection, mice were placed in their home cages for 10 min, then placed in the operant chambers for 5 min of habituation before beginning the rsChRmine effort task. For these agents, systemic injection was chosen over intracranial injection due to risk of brain injury from the necessary solvents.

For local injection experiments, mice were administered an intra-VTA infusion of muscimol 1 mM (Tocris) or intra-NAc infusion of DHβE hydrobromide 30 µg per hemisphere (Tocris), terazosin 3 µg (Tocris), osanetant 375 ng (Axon Medchem), scopolamine 22 nmol (Tocris) or ML375 105 pmol (Axon Medchem). Osanetant was dissolved in Tween 20% until homogeneous, then diluted to 1% Tween in filtered molecular-quality PBS to prevent precipitation. All other antagonists were dissolved in filtered molecular-quality PBS only. We also infused the GABAA antagonist bicuculline (Tocris) and the GABAB antagonist CGP 35348 (Tocris) into the NAc, but this treatment evoked severe motor deficits, including seizures in some cases, preventing mice from performing the task. Thus, we could not collect time-locked DA recordings during these infusions.

Drugs were infused through an injector cannula connected to a 5-µl Hamilton syringe using a microinfusion pump (Harvard Apparatus) at a continuous rate of 150 nl per minute to a total volume of 0.3 µl unilaterally or bilaterally. For unilateral infusions with fibre photometry recording, multiple fluid injection cannulas (400 µm diameter, 0.66 numerical aperture; OmFC, Doric) were used. For bilateral infusions, bilateral infusion cannulas (P1 Technologies) were used. Injector cannulas were removed 2 min after infusions were complete. After infusion, mice were placed in the operant chambers and allowed to habituate for 5 min before beginning the sucrose or rsChRmine effort task.

Validation of VTA DA cell body inhibition

To validate the effect of muscimol on VTA DA cell bodies, a cohort of DAT:IRES–Cre mice was injected with AAV9-syn-FLEX-jGCaMP8m into the VTA and implanted with multiple fluid injection cannulas (OmFC, Doric). To visualize the effect of muscimol in real time, one of these mice was prepared with a steel cross-bar for head-fixed recording during PBS or muscimol microinjection (Extended Data Fig. 4e–g). This mouse was habituated to a cylindrical enclosure and bilateral clamps were fixed to each side of the cross-bar. The pre-loaded injector was then inserted into the cannula and the recording began. After a 5-min baseline, the drug was injected and the recording continued for an additional 10 min. The injector was removed after the recording ended. Although this procedure allowed us to record photometry signals before, during and after the muscimol infusion, the head fixation prevented the animal from seeking or consuming liquid rewards in our behavioural setup. Thus, the remainder of the mice were not head fixed. Instead, they were microinjected with either muscimol or PBS immediately before a photometry recording that consisted of a 10-min baseline and then a 30-min, freely moving Pavlovian reward delivery session (the sucrose reward was delivered along with a sound or light cue every 30 s on average). Neural activity during both the baseline and Pavlovian reward task were then compared between muscimol and PBS sessions (Extended Data Fig. 4h–j). We chose the Pavlovian task because it minimized the motor requirements for these mice. Owing to the rotations elicited by muscimol, the mice could reliably enter one port (the magazine to consume sucrose), but not two (the active nose poke and the magazine), and thus they could not perform the sucrose task after muscimol infusion.

It was not technically possible to use fibre photometry to directly validate the effect of stGtACR on DA cell body activity because of saturation or photoswitching artefacts when this opsin is co-expressed with either green-shifted or red-shifted calcium sensors14,64,65,66. Instead, stGtACR was validated through GRAB DA recordings in the NAc (Extended Data Fig. 5e–g).

Slice electrophysiology

Acute brain slices were prepared from adult ChAT–Cre:DAT–Flp mice between postnatal days 120–180. ChAT–Cre:DAT–Flp mice were sterotaxically injected with 500 nl of AAVdj-eF1a-fDIO-eYFP into the VTA (−3.1 mm anteroposterior, +0.4 mm mediolateral and −4.2 dorsolateral) and AAV8-Ef1a-DIO-rsChRmine-oScarlet into the NAc (+1.5 mm anteroposterior, +0.9 mm mediolateral and −4.1 mm dorsolateral) at postnatal days 90–120 and were used for electrophysiology experiments 4–8 weeks post-injection. Mice were anaesthetized with isoflurane anaesthesia and transcardially perfused before decapitation. Brains were carefully extracted and 250-µm thick coronal slices were cut using a vibratome (Leica VT1200 S) in ice-cold slice solution containing 110 mM sucrose, 62.5 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 6 mM MgCl2, 1.25 mM KH2PO4, 26 mM NaHCO3, 0.5 mM CaCl2 and 20 mM d-glucose, pH 7.35–7.40. Slices were incubated in slice solution for 20 min at 33 °C, then transferred to a room-temperature holding chamber with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF; 125 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.25 mM KH2PO4, 26 mM NaHCO3, 2 mM CaCl2 and 20 mM d-glucose, pH 7.35–7.40). Brain slices were stored in room temperature ACSF and used for recording 30–300 min later. All solutions were saturated with carbogen.

Individual brain slices were placed in an RC-27 recording chamber (Warner Instruments) and superfused with carbogen-saturated ACSF (33–36 °C) at a flow rate of 2–3 ml min−1. eYFP-positive cut ends of axons (blebs) originating from the VTA present at the slice surface in the NAc were visualized with a BX51WI upright microscope (Olympus) equipped with epifluorescence, IR-DIC optics, 470 nm (ET-GFP 49002, Chroma) and 596/83-nm single-band bandpass (FF01-596/83-25, Semrock) filter cubes, and a ×40 0.8 NA water immersion objective (LUMPLFLN, Olympus). Perforated-patch recordings were made using parafilm-wrapped borosilicate pipettes filled with internal solution containing 135 mM KCl, 10 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 0.5 mM EGTA and 0.1 mM CaCl2, 280 mOsm, pH 7.4 adjusted with KOH. Recording electrodes (6–10 MΩ) were back filled with internal solution, then filled with internal containing 100 µg ml−1 gramicidin (Sigma). Pipette capacitance neutralization and bridge balance were manually adjusted before current clamp recordings. ChAT–Cre+ neurons expressing rsChRmine were optically stimulated with 10-ms transistor-transistor logic (TTL) pulses every 10 s using orange (596 nm) light ranging from 0.2 to 3 mW delivered through the microscope objective by an LED driver (Thorlabs). Baseline axonal responses to rsChRmine stimulation in ACSF were measured for 3 min, and the average response from the first 10 sweeps at baseline was compared with the average response from the final 10 sweeps during a 3-min period in the presence of 1 µM DHβE (Tocris). Acute application of DHβE was achieved via gravity-driven bath perfusion. Current clamp recordings were sampled at 20 kHz and filtered at 10 kHz using a MultiClamp 700B and Digidata 1550B and analysed using pClamp11 (Molecular Devices). Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m., where n or N represent the number of cells and animals, respectively.

Immunohistochemistry

Mice were transcardially perfused with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in PBS and brains were removed and post-fixed overnight at 4 °C. A vibratome (Leica Biosystems) was used to prepare 50-µm coronal sections. After three 10-min washes in PBS on a shaker, the slices were incubated with blocking solution (10% normal goat serum, 0.2% bovine serum albumin and 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS) for 1 h. After one 10-min wash in PBS, slices were incubated in primary antibodies using a concentration of 1:1,000 for 12–20 h at 4 °C on a shaker. Primary antibodies included rat mCherry monoclonal antibody (M11217, Invitrogen), chicken anti-GFP (GFP-1020, Aves Labs), mouse anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (MAB318, Millipore), and, to visualize TetTox, the mouse anti-2A peptide (MABS2005, Millipore). After three washes of 10 min in PBS, secondary antibodies were added at a concentration of 1:750 and incubated for 2 h at room temperature on a shaker. Secondary antibodies included goat anti-rat Alexa Fluor 594 (A11007, Invitrogen), goat anti-chicken Alexa Fluor 488 (AB150169, Abcam) and goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 647 (A21235, Invitrogen). Both primary and secondary antibodies were incubated with slices in a carrier solution (1% normal goat serum, 0.2% bovine serum albumin and 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS). After three more washes, the slices were mounted on SuperFrost Plus glass slides with DAPI Fluoromount-G mounting medium (Southern Biotech) for visualization using a Nikon A1 confocal microscope with NIS Elements AR software or a Keyence BZ-X800 microscope.

Data analysis

Subject mice were excluded (less than 5%) from the analysis if they did not reach behavioural criteria or on the basis of histology if they had (1) inaccurate implant placement, or (2) off-target or minimal transgene expression. MATLAB (MathWorks) scripts from Tucker-Davis Technologies were used for signal processing. Signals were downsampled by a factor of 10, underwent LOESS smoothing (window size of 30 ms) to reduce high-frequency noise and analysed in 15-s windows around the following timestamps: the first nose poke of each trial (excluding FR1 trials, where the first nose poke triggers reward delivery), reward delivery (which is coincident with a light–sound cue) and reward consumption (defined as when the mice first entered the magazine port after sucrose reward delivery). Entire sessions were debleached according to a previously published iterative method67 which calculates the dF/F in short moving windows, centres and normalizes these windows, and then repeats these calculations for 100 temporally offset windows in the same session. Z-scores were then calculated using the mean and standard deviation of the signal spanning the entire session to minimize confounds in behaviour contaminating the local baseline periods for trial-based methods of analysis. As a control, the analyses were all repeated in a different manner, using local baselines to calculate Z-scores, and the results were qualitatively identical.

To separate the contribution of individual behavioural events that occurred close in time, we (1) fit regression models to predict photometry data based on multiple variables (see below), and (2) examined neural activity on the subset of trials with large ITIs (for example, more than 30 or 60 s), which revealed similar results (for example, Extended Data Figs. 2, 9 and 10). All trials within a session were first combined into a single session average, and then sessions were averaged together for each mouse. All photometry figures in the article show the mean and standard error of the photometry signal across mice, which is a more conservative approach than using the trial or session average. To quantify neural activity, we used AUC — calculated using the trapezoidal numerical integration of the Z-scores for the windows defined in the figure legends — or calculated the maximum value in the windows denoted in the figure legends. Windows for quantification were chosen based on visual inspection of the traces and applied consistently throughout the analysis for any direct comparison between traces. To minimize bleaching confounds, we removed the first 5 min of each recording, when the steepest bleaching was likely to occur. We also limited our interpretations to short windows of data, avoiding any analysis of longer-timescale changes, which are more likely to be confounded by bleaching or other gradual changes (for example, slight adjustments in the connection between the implant and the patch cord), and more likely to vary depending on the exact debleaching strategy used. In addition, for GRAB DA recordings, we took the approach reported by Sych et al.68 and examined simultaneously recorded control signals (405 nm), which we found to be flat or slightly negative traces with substantially lower amplitude than what we observed with the experimental excitation (465 nm). Although this analysis is imperfect because 405 nm is not the isosbestic point for GRAB DA, the result implies that motion artefacts, bleaching or other intrinsic, non-DA-dependent signal changes could not have made a major contribution to our results.

To analyse spontaneous activity in VTA DA cell bodies after muscimol versus saline (Extended Data Fig. 4i), we debleached the signal by fitting a double-exponential curve and subtracting the fit from the raw data, and then used the MATLAB function findpeaks to identify all local peaks that were at least 1.5 Z-scores in prominence and 150 ms in width at half peak, as previously described69.

Kernel regression analysis

To quantify the contribution of behavioural variables to neural activity, linear mixed effects models were used as in previous work13,70,71,72,73. First, task-relevant behavioural predictors (for example, active nose poke, inactive nose poke, reward delivery, magazine entry, FR and ITI) were aligned to the photometry signal13,70,74. Behavioural events were assigned as fixed effects, represented in a predictor matrix X of dimension N × p, where N is the number of timestamps in the photometry recording and p is the number of predictor variables13. Variables were represented in binary form, indicating whether a behavioural event occurred at a given timestamp. The mouse from which the data were collected was treated as a random effect, stored in a sparse design matrix Z of size N × m, where m is the number of mice from which data were collected. The predictor matrix X was time shifted by T1 (T1 = 60 timeshifts per 1.5 s for sucrose; T1 = 100 timeshifts per 2.5 s for ChRmine) timestamps backwards and T2 (T2 = 125 timeshifts per 4 s for sucrose; T2 = 400 timeshifts per 10 s for ChRmine) timestamps forwards to encapsulate effects of behavioural variables on the signal at previous and future timestamps13. The new, time-shifted predictor matrix was of dimension N × p(2(T1 + T2) + 1). Data for timestamps at which no behavioural event of interest occurred, or which did not fall within the [−T1, T2] timestamps of a behavioural event, were excluded. The fixed effects matrix X and random effects matrix Z were used to train a linear mixed effects model of the form y = Xβ + Zµ + ε, where y is the N × 1 dimensional response vector consisting of the photometry signal values at each timestamp, β is a p(2(T1 + T2) + 1) × 1 vector of β-coefficients for each time-shifted predictor variable, µ is an m × 1 vector of coefficients for each random effect, and ε is an N × 1 vector representing the residual variance that cannot be explained by the fixed or random effects. Response kernels were generated and plotted over the time window for each behavioural variable representing the contribution of each behavioral variable to the predicted fibre photometry signal13,70,74. The observed signal was plotted against the predicted signal to demonstrate the efficacy of the model fit. The model was trained using tenfold cross-validation; reported R2 values and plotted β-coefficients are the average across model runs for all tenfolds. The relative contribution of each behavioural variable to the total photometry signal was determined by performing a leave-one-out analysis where behavioural variables were sequentially removed from the model to observe the change in the overall predictive ability of the model as quantified by the R2 value. The relative contribution of a variable was then defined as the proportional change in R2 when that variable was removed from the model71.

Single-cell RNA sequencing analysis

We accessed the whole mouse brain 10X single-cell RNA sequencing datasets made publicly available by the Allen Institute75. We analysed neurons that belong to cell classes already identified by the Allen Institute for each brain region. We restricted our analysis to the midbrain, striatal ventral region, anterior cingulate region, hippocampal region, prelimbic/infralimbic/orbital areas, thalamus and cortical subplate. Within each region outside of the NAc and midbrain, we examined cell types predicted to project to the NAc. We extracted expression levels for major cell types local to the region of interest, focusing on the following nicotinic α-subunit genes: Chrna1, Chrna2, Chrna3, Chrna4, Chrna5, Chrna6 and Chrna7. Transcript expression was quantified by calculating the log2(CPM + 1), where CPM is counts per million. The percentage of cells expressing each transcript was also quantified. These analyses were performed in Python with custom scripts and notebooks from the Allen Institute.

Statistics and reproducibility

Investigators were blinded to the manipulations that experimental subjects had undergone during the behavioural testing, recordings and data analysis. All photometry analysis and behavioural analysis was conducted in MATLAB. Quantifications of the photometry and behavioural results were graphed and analysed using GraphPad. All data were tested for normality of sample distributions using the Shapiro–Wilk normality test, and when violated, non-parametric statistical tests were used. Normally distributed data were analysed by paired, two-tailed t-tests, or one-factor or two-factor repeated measures analysis of variance. Non-normally distributed data were analysed using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test or Friedman’s test. When data were not paired, unpaired t-tests or the Mann–Whitney rank test was performed for normally and non-normally distributed data, respectively. If individual data points were missing from these matched comparisons, mixed-effects models were used instead. Mixed-effects models were also used when examining the effects of multiple fixed effects (for example, FR and drug), accounting for the random effect of subject. In these cases, the significance of the fixed effects was reported in the figure legends and if there were significant fixed effects, Sidak-corrected post-hoc comparisons were reported with asterisks in the figures. Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to compare three or more unmatched groups (for example, DA responses from trials with different ITIs). Spearman correlations were used to measure the association between two independently measured observations (for example, rewards on consecutive days). Fluorescent micrographs are representative of six mice (Fig. 1a), eight mice (Fig. 1l), six mice (Fig. 2b), six mice (Fig. 2d), eight mice (Fig. 2g), six mice (Fig. 3b), six mice (Fig. 3h), three mice (Fig. 3n), eight mice (Fig. 4a), eight mice (Fig. 4g, top), six mice (Fig. 4g, bottom), six mice (Fig. 5a), eight mice (Fig. 5g), six mice (Extended Data Fig. 6a), nine mice (Extended Data Fig. 10a) and seven mice (Extended Data Fig. 11a). For experiments involving multiple groups, subjects were randomly assigned to experimental conditions. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. All statistical tests were two-sided and performed in MATLAB (Mathworks) or Prism (GraphPad). NS, not significant. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001. In all figures, data are shown as mean ± s.e.m.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.