Husbandry of experimental animals

Female frog (X. laevis) adults and zebrafish adults were maintained and handled according to established protocols43,44. Frogs were acquired from Nasco (LM00531) and Xenopus1 (4800). The experiments were approved and licensed by the local animal ethics committee (Landesdirektion Sachsen; license no. DD24-5131/367/9, 25-5131/521/12 and 25-5131/564/25 for frogs and license no. DD24.1-5131/394/33 for zebrafish) and carried out following the European Communities Council Directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes, as well as the German Animal Welfare Act. Drosophila stocks were maintained at room temperature using standard methods.

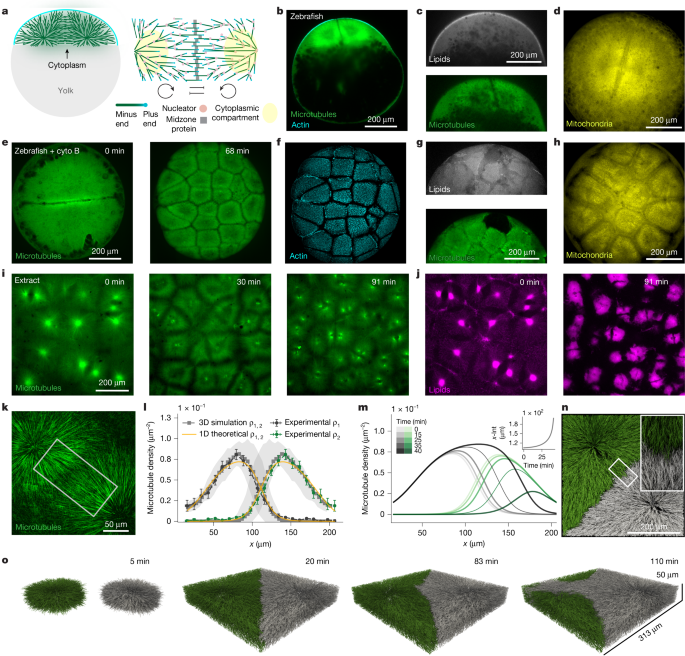

Zebrafish and Drosophila transgenic lines used

The following transgenic zebrafish lines were used. Tg(actb2:EGFP-Hsa.DCX) for microtubule visualization, Tg2(actb2:mCherry-Hsa.UTRN) for actin visualization, their double-transgenic Tg(actb2:EGFP-Hsa.DCX; actb2:mCherry-Hsa.UTRN) and Tg(Xla.Eef1a1:mlsEGFP)45 for mitochondrial compartmentalization. The following fly lines were used. For transgenics: wild-type (w[1118]), Pw[+mC]=PTT-GAJupiter[G00147] (BDSC 6836; FlyBase: FBst0006836) expressing Jupiter–GFP, Pw[+mC]=His2Av-mRFPII.2* (BDSC 23651; FlyBase: FBst0023651) expressing histone–RFP, and w[1118]; Pw[+mC]=osk-GAL4::VP16F/TM3, Sb[1] (BDSC 44242; FlyBase: FBst0044242), used as a maternal Gal4 driver for UAS lines. A double-transgenic line (yw; His2Av-EGFP/CyO; TMBD-mCherry/TM6B, Tb) was used to visualize histones and microtubules. A EB1–GFP line w[1118]; Pw[+mC]=ncd-EB1.GFPM1F3 (BDSC 57327; FlyBase: FBst0057327) was used to track EB1 comets. A photoconvertible α-tubulin under UAS line was used for photoconversion: w[*]; Pw[+mC]=UASp-alphaTub84B.tdEOS7M (BDSC 51314; FlyBase: FBst0051314).

Cytoplasmic extract and cell-cycle manipulations

Cytoplasmic extracts from frog eggs were prepared following standard protocols46,47. The following buffers were prepared in advance: Ten times Marc’s modified Ringer’s (MMR; 1 M NaCl, 20 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 20 mM CaCl2, 1 mM EDTA and 50 mM HEPES in milliQ water), with pH was adjusted to 7.8 with NaOH and the solution was filter sterilized and stored at room temperature; 20× Xenopus buffer (2 M KCl, 20 mM MgCl2 and 2 mM CaCl2 in MilliQ water), with pH adjusted to 7.7 with KOH; 1 M HEPES solution was prepared and pH was adjusted to 7.7 and after filter sterilization, the solution was stored at 4 °C; and a 2 M sucrose solution. The solutions were filter sterilized and stored at 4 °C. Female adult frogs were injected with 0.5 ml of pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (779-675, Covetrus) and 0.5 ml of human chorionic gonadotropin (CG10-10VL, Sigma) 3–8 days and 1 day before the experiment, respectively. After the second injection, frogs were incubated at 16 °C for 18 h in a 1× MMR solution. Of MilliQ water, 3 l was incubated at 16 °C to be used for buffer preparation. On the experiment day, the following buffers were prepared: 1 l of dejelly buffer (20 g of L-cysteine (W326305, Merck), 50 ml of 20× Xenopus buffer and MilliQ water), with pH adjusted to 7.8 with NaOH; 1 l of 0.2× MMR, with pH adjusted to 7.8 with NaOH; 1 l of 1× Xenopus buffer (20× Xenopus buffer in MilliQ, 50 mM sucrose, 10 mM 1× HEPES), with pH adjusted to 7.7 with KOH; 100 ml of calcium ionophore solution (CaIo; 5 µl of calcium ionophore (A23187, Sigma) in 100 ml of 0.2 MMR buffer); Xenopus buffer+ (100 µl of 10 mg ml−1 solution of leupeptin (15483809, Thermo Scientific), pepstatin (2936.2, Roth) and chymostatin (230790, Calbiochem) in 1× Xenopus buffer). Frog eggs were dejellyed by multiple washes with the dejelly buffer. Eggs were then washed multiple times with 1 l of 0.2 MMR buffer and then incubated in the CaIo solution to activate the cell cycle. During the dejelly and activation, eggs were swirled to achieve uniform contact with chemicals and avoid egg aggregation. The activation process lasted 3–5 min, depending on egg number, and was continued until the animal pole became smaller and darker. The eggs were then washed multiple times with 1 l of Xenopus buffer and then 3× with 250 ml of Xenopus buffer+. Next, eggs were transferred to centrifuge tubes (344057, Beckman) containing 1 ml Xenopus buffer+ and 10 µl of cytochalasin B (15466849, Thermo Scientific). Tubes were sequentially centrifuged for 30 s at 500 RPM and for 1.5 min at 2,000 RPM for egg packing. After the excess buffer was removed with an aspirator, eggs were crushed by centrifugation for 15 min at 10,000 RPM at 4 °C. The centrifuge tubes were placed on ice and the cytoplasmic layer was collected by puncturing the tube. Additional LPC (leupeptin–pepstatin–chymostatin) (1/1,000 w/v) and cytochalasin B (1/1,000 w/v) were added to further prevent protein degradation and actin polymerization. The extract was stored in ice and used on the same day. Interphase-arrested extract was obtained as described above but 200 µl of cycloheximide (239763, Merck; 10 mg ml−1) were added to the centrifuge tubes with the Xenopus buffer+.

Extract sample preparation and imaging

The extract was supplemented with de-membraneted sperm to induce nuclei formation and fluorescent labels for visualizing cellular structures. Reactions were set up by mixing 25 µl of undiluted extract, 0.6 µM pig tubulin labelled with 647 Alexa fluorophore48, 0.12 mg ml−1 GFP-NLS, 0.2 µl of 1:250 diluted stock in water of octadecyl rhodamine B chloride (O246, Invitrogen) and 1 µl of sperm (3,000 sperm per microlitre) in an Eppendorf tube in ice. Reactions were supplemented with the following: anti-INCENP (0.5 µl of antibody (ab12183, abcam) labelled with Alexa Fluor 488 NHS Ester (A20000, Thermo Fisher) instead of GFP-NLS), AurkA beads (1 µl)30, Ran(Q69L)16 (30 µM), MCAK-Q710 (1 µl of 1.5 mg ml−1 added). Dynein inhibitor p150-cc1 (concentrations reported in Extended Data Figs. 4 and 5), barasertib (40 µM; S1147, Selleckchem), purified centrosomes from Droosophila embryos (HisGFP-TauMCherry line) and HeLa cells were prepared using existing protocols49,50 (3 µl added to the reaction). The treatment with morpholino to selectively block translation of cyclin B1 and B2 and arrest the cell cycle was performed by mixing 2.5 µl of each the following morpholinos in a solution and then adding 1–5 µl of it to the extract reaction: morpholino anti-Xenopus cyclin B1 (ccnb1a): ACATTTTCCCAAAACCGACAACTGG; morpholino anti-Xenopus cyclin B1 (ccnb1b): ACATTTTCTCAAGCGCAAACCTGCA; morpholino anti-Xenopus cyclin B2 (ccnb2l): AATTGCAGCCCGACGAGTAGCCAT; and morpholino anti-Xenopus cyclin B2 (ccnb2s): CGACGAGTAGCCATCTCCGGTAAAA. The morpholinos were acquired by custom order to Gene Tools and the sequences were chosen from previous works27,28. For slowing the cell cycle, extract reactions were supplemented with 4 µl of cycloheximide in varying concentrations from 2.5 g l−1 to 7.5 g l−1. We could not link a specific concentration to a cell-cycle duration, probably because the amounts of cyclins vary from sample to sample. In all the experiments, the reactions were flicked multiple times and left for 3–5 min in ice to homogeneously distribute the reagents in the extract. Of the reaction, 6 µl was taken from ice, and added either on a 35-mm glass bottom dish (P35G-0.170-14-c, MatTek) and covered with 1 ml of mineral oil (m3516, Sigma) or a 15 µ-Slide eight well (80826, Ibidi) and covered with 300 µl of anti-evaporation oil (50051, Ibidi). The oil was necessary to allow oxygen exchange and viability of the sample for long-term imaging. For the experiments of droplet confinement (Fig. 4j), 10 µl of the reaction with morpholinos was added droplet by droplet in a tube with 0.5 ml mineral oil. The tube was flicked three times to break the droplets into smaller droplets. The reaction droplets in oil were then transferred to a coverslip with a spacer (GBL654004, Grace Bio-Labs) and a second coverslip was used to seal the top. During this process, some air droplets formed in the oil, allowing for oxygen exchange. A well with a different coating that allows for imaging at low magnification with higher resolution was used for Supplementary Videos 4 and 10 in the MCAK case (80800, Ibidi). Imaging was performed with a spinning disk confocal microscope (IX83 Olympus microscope with a CSU-W1 Yokogawa disk) connected with two Hamanatsu ORCA-Fusion BT Digital CMOS camera (SD1). Z-stacks were acquired with a stage-top Z piezo and 10–20-µmz-spacing.

FRAP, EB1 and speckle imaging in extract

Of cytoplasmic extract, 25 µl was supplemented with 1 µl of sperm (3,000 sperm per microlitre), 0.6 µM of pig tubulin labelled with 647 Alexa fluorophore and 0.16 µM EB1–mApple22 to image the plus ends of the microtubules. The sample was imaged with SD1 and Olympus ×40 Air (0.65 NA) objective, and extract supplemented with beads was imaged with Olympus ×100 (1.35 NA) silicon oil. Every 2 min, we sequentially acquired five images of EB1 comets 3 s apart followed by one image of tubulin, following existing protocols14. This choice for the framerate allowed us to minimize bleaching of EB1 and follow the EB1 tracks over time. These reactions were also used for FRAP experiments in the case of extract supplemented with purified centrosomes. The FRAP experiments were performed with SDType1 equipped with a photoactivation module, an Olympus ×40 Air (0.65 NA) objective and a 405-nm laser. For speckle imaging, cycling extract was supplemented with 10 nM of Atto 567-labelled tubulin. The extract was encapsulated between two coverslips separated by a spacer (GBL654004, Grace Bio-Labs) to lower the background noise and prevent aster movement. Because the encapsulation restricts oxygen exchange, the reaction was imaged for 15 min. The speckles were imaged with SDType1 and an Olympus ×60 (1.3 NA) silicon oil objective with low laser intensity and at least 2-s exposure time.

Zebrafish embryo sample preparation

Embryos were collected in E3 medium (5 mM NaCl, 0.17 mM KCl, 0.33 mM CaCl2 and 0.33 mM MgSO4) within 15 min after spawning and kept at 24–28 °C. Embryo clutch quality was inspected on a dissection stereomicroscope and staged according to morphological criteria51. Embryos were mechanically dechorionated and mounted in 1% low melting-point agarose (A9414, Sigma-Aldrich) in E3 medium supplemented with 25% w/v iodixanol (OptiPrep, 07820, STEMCELL Technologies) for refractive index matching in a CELLVIEW cell culture glass bottom dish (627860, Greiner bio-one). Embryos were brought closer to the coverslip surface by keeping the dish upside down until agarose solidified.

Syncytial embryo and cell-cycle arrest

Dechorionated embryos at the one-cell stage were treated with 10 µg ml−1 cytochalasin B, which prevented cytokinesis. The stage of the embryo could be determined by minutes post-fertilization and by comparison with control embryos. When cytochalasin B (15466849, Thermo Scientific) treated embryos had reached the four-cell stage, they were mounted in 1% low-melting-point agarose containing 25% OptiPrep density gradient medium and supplemented with 200–400 g ml−1 cycloheximide and 10 µg ml−1 cytochalasin B in a glass-bottom dish (627860, Greiner bio-one). For the microtubule depolymerizing drug SbTubA4P52, when cytochalasin B-treated embryos had reached the 4–8-cell stage, they were mounted in 1 ml of 0.5% low-melting-point agarose supplemented with 50 µl cycloheximide (10 mg ml−1 stock), 1 µl cytochalasin B (10 mg ml−1 stock) and 5 µl SbTub (10 mM stock activated with blue light).

Embryo injections

Droplets were injected into the cytoplasm of one-cell-stage transgenic zebrafish embryos53. Injection volumes were calibrated to 0.5 nl. Depending on the experiment, 0.5–1 nl was injected per embryo. Ferrofluid droplets54 were injected without magnetic activation. Embryos were injected with PH-Halo (plextrin homology domain of PIP2: 4.64 mg ml−1 tagged with JF646 (2 µl PH protein and 2 µl JF dye). Embryos were incubated for a few minutes to allow the injection wound to heal and then manually dechorionated and mounted in cytochalsin B containing LMP. Dynein inhibitor p150-cc1 1 nl of 35 mg ml−1 inhibitor was injected into each embryo.

Imaging of zebrafish embryos

For Fig. 1a,b, a zebrafish embryo with chorion was positioned in an agarose column and imaged with a Zeiss LightSheet Z.1, following existing protocols55. For Fig. 4f,g and Extended data Fig. 10i, embryos were imaged with a spinning disk confocal microscope (IX83 Olympus microscope with CSU-W1 Yokogawa disk) connected with two iXon Ultra 888 monochrome EMCCD cameras (Andor; SD2). A ×30 NA 1.08 silicone oil objective (Olympus) was used. Z stacks were acquired with a stage piezo and 1–2 µm z-spacing. In all the other figures, imaging was performed with SD1 and an Olympus ×20 (0.80 NA) air objective. In all experiments, the embryos were kept at 28 °C with a temperature incubator.

FRAP and EB1 in zebrafish embryo

For EB1 experiments, cbg5Tg embryos were prepared and mounted as described above. The embryos were injected at the one-cell stage with 1.5 nl of a solution comprising 1.5 mg ml−1 EB1–mApple in Xenopus buffer. Embryos were imaged with SD1 equipped with an Olympus SApo ×60 (1.3 NA) silicon oil objective. Every 2 min, we acquired five consequent images separated by a time delay of 3 s, to avoid bleaching. For FRAP experiments, double-transgenic embryos were prepared and mounted as described above. The embryos were injected at the one-cell stage with 1.5 nl of a solution comprising of 2 µl of pig tubulin labelled with Alexa 647 and 8 µl of Xenopus buffer. The embryos were imaged with an Andor IX 81 microscope through a ×10 0.4 NA Air Olympus objective and a Yokogawa CSUX1 spinning disk (SD3). The FRAP experiments were performed with the FRAP module FRAPPA and a 640-nm solid-state laser.

Drosophila embryo preparation and imaging

Before imaging, w1118 males and females of the genotype of interest were housed in a cage covering an apple juice plate at 25 °C, supplemented with yeast paste. Embryos were collected over 2 h on a fresh plate, dechorionated with 50% bleach for 1 min and mounted in Halocarbon oil 27 (9002-83-9, Sigma) on a gas-permeable membrane for imaging. For the cycloheximide treatment, embryos were soaked in 10% concentrated cleaner and degreaser (Citrasolv) for 1 min after dechorionation and mounted in 1 mM cycloheximide (97064-724, VWR) for imaging. For the last two movies in Supplementary Video 12, on the left, the embryos were imaged on a Leica SP8 laser scanning confocal microscope equipped with a Leica ×20 oil-immersion objective (0.75 NA); on the right, the embryos were imaged with a Leica SP8 microscope using a Leica ×63 oil objective (1.40 NA).

EB1 and photoconversion in Drosophila

For EB1 comet tracking, embryos of the EB1–GFP line were mounted as described above and imaged with SD1 and an Olympus ×100 silicon oil objective (1.35 NA). Embryos were imaged for minutes with a frame rate of 1 s. For the photoconversion experiments, embryos of the photoconvertible tubulin were mounted as described above. Photoconversion experiments were performed on the Leica SP8 microscope with the FRAP module in the Leica Application Suite X (LAS X). Experiments were acquired using a Leica ×63 oil objective (1.40 NA) and a 405-nm bleaching laser.

Injection experiments in Drosophila

The embryo preparation follows the description above with the changes: males and females of the same genotype (HisGFP-TauMCherry line) were crossed and collection was performed for 30 min to obtain embryos as early as possible. After collection and dechorionation, 10–30 embryos were aligned on an agarose plate with a brush. They were then positioned on a glass coverslip covered with a thin layer of heptane glue and equipped with two spacers on top of each other (SecureSeal, Grace Bio-Labs). Embryos were desiccated in a box with dehydrating beads (Drierite desiccants, w.a. Hammond Drierite) for 7 min and then covered in Halocarbon oil. After desiccation, embryos were injected under a stereo-microscope with a glass needle and 5–10% of the embryo volume. Concentrations at the needle were 0.1 mg ml−1 for cycloheximide and 0.004 mg ml−1 for cytochalasin B. The sample was then covered with a glass coverslip and the embryos imaged with SD1 and an Olympus ×60 (1.3 NA) silicon oil objective.

Statistics and reproducibility

We chose sample sizes based on similar datasets used in the field, consistency of phenotypes and experimental challenges. Experiments were replicated over about 3 years with different microscopes and for some conditions different experimenters. The number of biological replicates is indicated as the number of independent samples and it refers to independent experiments for the in vitro extract studies and embryo number for in vivo studies. We have reported these numbers in the legend for plots with error bars and histograms. For the microtubule density profiles (Figs. 1l, 3c,e,g and 4e,k and Extended Data Fig. 8b,e,f,h), the number of independent samples are reported on Supplementary Table 1. For measurements of microtubule dynamics (Figs. 3a and 4c,d and Extended Data Fig. 9c), they are reported on Supplementary Tables 1–3. Technical replicates are reported in the adjacent columns. Here we have provided the number of biological replicates for images representative of phenotypes: for Fig. 1b, imaging of the microtubules and actin first in the cell cycle in the zebrafish embryo was repeated n > 20 times with confocal spinning disk and n = 1 with light sheet for visualization purposes; for Fig. 1c, n = 4; for Fig. 1d, n = 8; for Fig. 1e,f, n > 20; for Fig. 1g, n = 4; for Fig. 1h, n = 8; and for Fig. 1i,j,k, n > 20. For Fig. 2a,b, invasion events were n > 20. For Fig. 3d,f, n > 5; For Fig. 3h, n = 8; and for Fig. 3i, n = 4. For Fig. 4a,b,f,l, n > 20; and for Fig. 4j, n = 1 specifically with confinement in droplets, but n > 20 to test morpholinos in extract. For Fig. 5, the specific videos were acquired as n = 1 as proof of concept; however, these dynamics were observed n > 20. For Extended Data Fig. 1b, n = 8; for Extended Data Fig. 1c, n = 4; for Extended Data Fig. 1e, n = 1; for Extended Data Fig. 1f, n = 12; for Extended Data Fig. 1h,i, n > 20; and for Extended Data Fig. 1k, n = 8. For Extended Data Fig. 2g, n > 20; and for Extended Data Fig. 2h, n = 3. For Extended Data Fig. 4a,e, n > 5; and for Extended Data Fig. 4d, n = 3. For Extended Data Fig. 5, n > 5. For Extended Data Fig. 6, n > 20 invasion events. This is a representative analysis of the event. For Extended Data Fig. 6e, n > 5; and for Extended Data Fig. 6f, n = 3. For Extended Data Fig. 7a, n > 20 invasion events. This is a representative analysis of the event to show the method to find the invasion time. For Extended Data Fig. 8c,d, n = 6; for Extended Data Fig. 8g, n = 2; and for Extended Data Fig. 8i,j, n > 5. For Extended Data Fig. 10a, n = 11; for Extended Data Fig. 10b, n = 12; for Extended Data Fig. 10c, n = 9; for Extended Data Fig. 10g, n = 8; for Extended Data Fig. 10h, n = 14; and for Extended Data Fig. 10i, n > 5. Plots showing single lines without errors are relative to specific images or Supplementary Videos (Fig. 5e in the main text and Extended Data Figs. 1b,d,g,j, 2c, 4d,g, 6b–e, 7b–d and 10d,e). These plots are based on the quantification of a single example of a phenotype that was replicated with the n value related for the figures and reported above. In the analysis of the role of cell-cycle times (Fig. 2g,h) and invasion times (Fig. 2d), experiments were analysed in a random order as there was no previous knowledge on the possible outcome. For the other experiments, randomization was not performed and each condition was analysed separately. We did not perform blinding. Data were excluded if embryos or extract underwent early apoptosis.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.