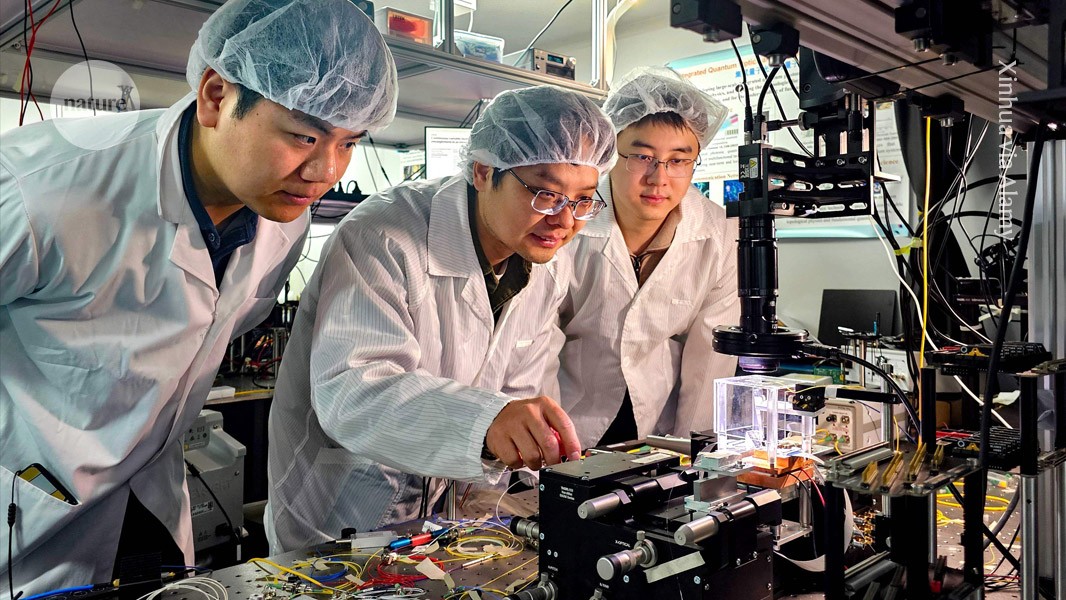

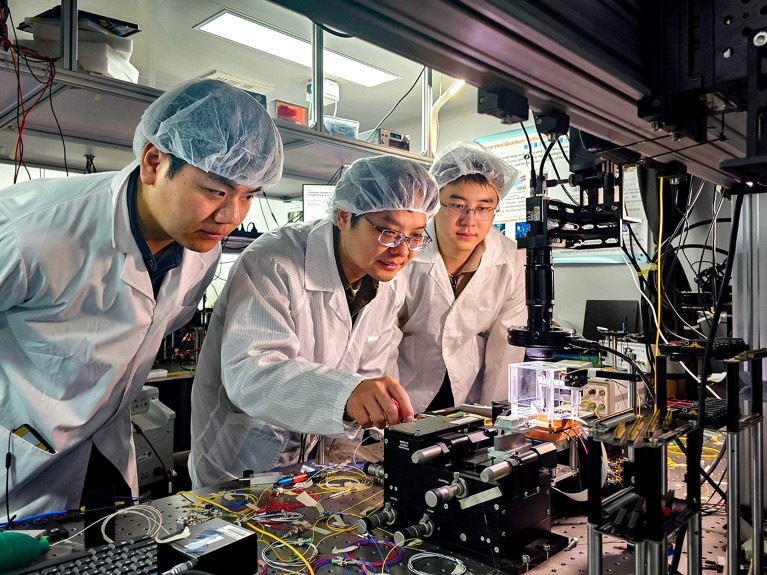

Researchers at Peking University in China test an integrated photonic quantum chip.Credit: Xinhua via Alamy

As generative artificial-intelligence models become more sophisticated and eat up more energy to produce images and videos, the electronic chips that power them are reaching their limits of speed and efficiency. Optical chips – semiconductor chips that run on light rather than electricity – could solve these problems, say researchers working in the field.

Such chips, also called photonic chips, are still years away from being integrated into consumer computers and are unlikely to wholly replace electronic chips. However, optical chip research has grown drastically in the past five years, with China leading the charge.

“China has for the past decade invested strategically in infrastructure, capability and talent” in this field, says Ben Eggleton, a physicist at the University of Sydney, Australia. Eggleton, who was the editor-in-chief of APL Photonics for more than a decade until his tenure ended in December 2025, says that he has seen an increase in the number of high-quality publications on photonic chips from China.

Chinese researchers published 476 papers on optical chips last year, the most of any country, according to a Nature analysis of papers in the Dimensions database (part of Digital Science, a firm operated by the Holtzbrinck Publishing Group, which has a share in Nature’s publisher, Springer Nature). The number of Chinese-authored papers grew by tenfold between 2017 and 2025. The United States was the next top producer, with an output that more than doubled during that period.

China’s embrace of optical computing has accelerated in the wake of US policies to limit China’s access to the most advanced electronic chips and to restrict the equipment necessary to manufacture them. Such chips are needed to train and deploy large AI models.

The restrictions have sharpened China’s incentive to find alternative pathways to high-performance computing, says Zengguang Cheng, a materials scientist at Fudan University in Shanghai, China. “China’s 14th five-year plan finds mention of photonics, along with quantum computing projects. China’s government has provided sustained investments for this,” he adds.

Computation challenges

Optical chips transmit information using photons rather than electrons. Because photons travel fast and do not shed energy as heat, optical systems can perform better than electronic ones and have lower energy loss. Such chips are already found in sensors, data communication systems and biomedical devices. But using them to perform computation — particularly for generative AI tasks — poses extra challenges.

Electronic chips manipulate voltages using transistors. Photonic chips, by contrast, depend on controlling the amplitude, phase and interference patterns of light. This makes them energy efficient but harder to scale, reconfigure and train for complex tasks, says Yitong Chen, an electronic engineer at Shanghai Jiao Tong University in China. Until recently, most photonic chips could perform only narrow functions, such as classifying images.

Last month, Chen and colleagues unveiled the first all-optical chip1, called LightGen, that can run advanced generative AI models to produce images and videos.

The researchers used densely integrated metasurfaces — stacked layers engineered to manipulate light at the nanoscale, which allowed them to integrate millions of photonic neurons into the chip. They also developed a training algorithm tailored specifically for optical systems. According to the team, LightGen generated images, edited video content and even produced 3D scenes at speeds and energy efficiencies exceeding those of high-end processors, such as NVIDIA’s A100.

Eggleton says that the work is an impressive proof of concept for a fast and energy-efficient photonic chip that can complete specific tasks.