Biobank Japan

The BBJ is a prospective hospital-based biobank with 267,289 participants, all of whom were diagnosed with at least one of the target diseases of BBJ by physicians at the cooperating hospitals50,51,52. All of the participants provided written informed consent approved by the ethics committees of the Institute of Medical Sciences, the University of Tokyo and RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Sciences. The BBJ comprises two cohorts, which were genotyped separately: the first (BBJ1, N = 182,536) and second (BBJ2, N = 68,534) cohorts. The participants in BBJ1 were genotyped with the Illumina HumanOmniExpressExome BeadChip or a combination of the Illumina HumanOmniExpress and HumanExome BeadChip, whereas the participants in BBJ2 were genotyped with the Illumina Asian Screening Array. All BBJ1 participants and 17% of the BBJ2 participants (N = 11,716) were recruited from 2003 to 2008. The remaining BBJ2 participants (N = 56,818) were recruited from 2013 to 2017.

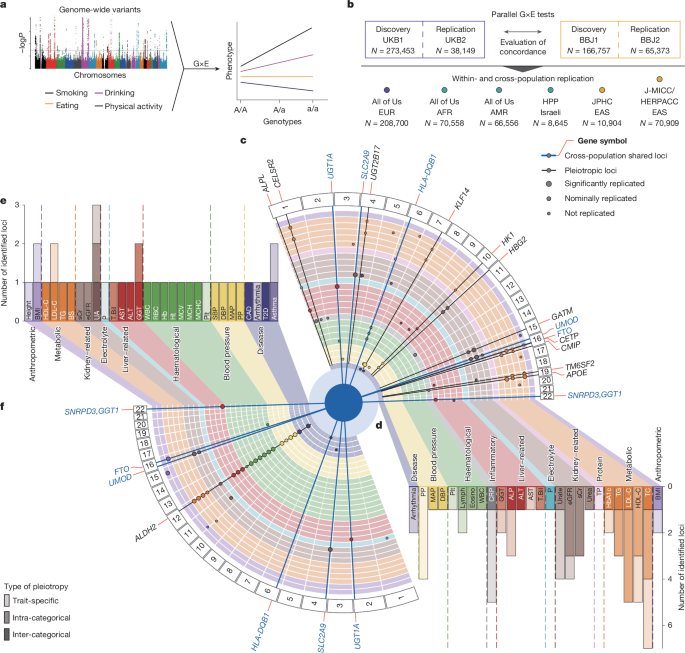

Definition of the discovery and replication cohorts

We used BBJ1 (BBJ2) as the discovery (replication) cohort.

Quality control of genotype data

We conducted a quality control of the participants and the genotypes, and excluded sample relatedness in BBJ1 via the same approach described previously53. The genotype data were imputed with 1000 Genomes Project Phase 3 (N = 2,504) and Japanese whole-genome sequencing data (N = 1,037) using Minimac3 software54. We excluded variants with an imputation quality of Rsq < 0.7 or a minor allele frequency (MAF) of less than 0.01, resulting in 7,444,735 autosomal variants analysed in total. We analysed 166,757 participants of the Japanese population as estimated by the visual inspection of principal component analysis (PCA).

In BBJ2, we excluded participants with a low call rate (<0.98) and outliers from the Japanese Hondo (that is, the main islands) cluster estimated on the basis of PCA. We excluded the variants meeting the following criteria: (1) with a low call rate (<0.99); (2) with low minor allele counts (<5); and (3) with a Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium test P value of <1.0 × 10−10. We performed statistical phasing of the genotype data using Shapeit4 (ref. 55) and imputation using Minimac4 (ref. 56) with the same reference panel as used in the discovery cohort. After imputation, we excluded variants with an imputation quality of <0.7 or a MAF less than 0.01. We used King57 to exclude relatives within second degrees, resulting in 65,373 participants being analysed.

UK Biobank

The UKB is a population-based biobank with approximately 500,000 participants recruited between 2006 and 2010, aged 40–69 years58. Participants were genotyped using either the UK BiLEVE Axiom Array or UK Biobank Axiom Array. The genotypes were then imputed by IMPUTE4 software using a combination reference panel of the Haplotype Reference Consortium, UK10K and 1000 Genomes Project Phase 3. We accessed the UKB data under the project number 47821.

Definition of the discovery and replication cohorts

We included British European for the discovery cohort (UKB1), defined as the intersection of the self-reported British participants and the genetically ‘Caucasian’ participants (UK Biobank Data Fields 21000 and 22006), to strictly reduce the inflation of test statistics due to population stratification. We excluded one participant from every related pair within the third degree. For the replication cohort (UKB2), we included all other genetically ‘Caucasian’ participants and excluded one participant from every related pair within the second degree. We also excluded the participants related to any participants in UKB1 within the second degree.

Quality control of genotype data

We analysed 9,813,264 autosomal variants with an imputation quality of >0.7 and MAF of >0.01, which was equivalent to the threshold used in BBJ. We excluded participants with: (1) sex chromosome aneuploidy; (2) a mismatch between genetic and self-reported sex; or (3) outliers for heterozygosity or missing rate.

Descriptions of the independent replication cohorts, J-MICC/HERPACC (refs. 59,60,61), JPHC (ref. 62), All of Us (ref. 63) and HPP (ref. 64) are available in Supplementary Methods.

Quality control of phenotypes and environments

Clinical traits

The definition and quality control of clinical traits were summarized in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3. In brief, we obtained biomarker phenotypes from the initial assessment data for UKB and the medical records for BBJ. For BBJ, we used the biomarker phenotypes measured at the nearest dates to the baseline assessment for the main analyses, whereas we used those measured most recently for the temporal order analyses. For the UKB, we used the baseline assessment data for the main analyses, whereas we used the most recent data from the second to fourth revisit assessments for the temporal order analyses, namely, the first repeat assessment visit, the imaging visit, and the first repeat imaging visit. We applied the same quality controls for both biobanks, including (1) excluding participants with age <18 or age >85; (2) excluding participants with particular disease status that might have affected the phenotype values; (3) correction of phenotype values for participants taking anti-hypertensive medications or statins; (4) excluding outliers whose measured values were outside of three times the interquartile range (upper or lower quartile), or outside three standard deviations from the mean; and (5) applying natural log transformation for the phenotypes with right-skewed distributions. For the temporal order analyses, we restricted the data to those measured at least half a year after the baseline survey.

For disease statuses, we combined diagnoses data (ICD-10), operation data (OPCS-4) and self-reported illness and operation data for UKB. We determined the subtypes of diabetes mellitus based on ICD-10 codes and an established algorithm developed for UKB self-reported data65. We excluded participants with diabetes mellitus other than T2D, and patients with T2D who were also inferred to have type 1 diabetes from both cases and controls. Following a previous report66, we included ischaemic stroke patients as cases only if they had any evidence of stroke other than self-reports and excluded the participants with self-reported stroke from controls. For BBJ, we defined disease statuses based on the union of diagnoses by doctors at the cooperating hospitals and past medical history retrieved from electronic medical records. When testing T2D, we excluded the participants with diabetes mellitus other than T2D from both cases and controls. We defined clinical traits and performed quality control in the replication cohorts in the same manner, as detailed in Supplementary Methods.

Environmental factors

As the resolution of individual questionnaire items was limited due to their few discrete response options, we employed a clustering-based approach to summarize correlated items into high-resolution latent environments67 as summarized in Supplementary Table 4. The questionnaires for dietary consumption and physical activity were available for both UKB and BBJ, with low missing rates (0.01–0.27% in UKB1 and 1.4–13.3% in BBJ1), and were used in this manuscript. We converted the categorical responses into the continuous scale following ref. 68. For example, the responses to dietary consumption in BBJ were ‘Almost every day’, ‘3–4 days a week’, ‘1–2 days a week’ and ‘Rarely’, and we converted them into 7, 3.5, 1.5 and 0, respectively. We treated the responses ‘Do not know’ and ‘Prefer not to answer’ as missing values. For clustering analyses, we first regressed out age, sex, age2, age × sex, and age2 × sex from the environmental factors derived from questionnaires about dietary consumption and physical activities. We then performed consensus clustering analyses using the ConsensusClusterPlus R package69 for the environmental factors. We used (1 − Pearson’s correlation) as the distance between environmental factors and employed the hierarchical clustering algorithm with Ward’s method. We note that we multiplied the values of coffee consumption in UKB1 by −1 as we observed its strong negative correlation with tea consumption. We changed the number of consensus clusters from two to ten and defined the number of clusters based on the stability of the cumulative distribution function curve and the item tracking. We named these clusters based on the questionnaire included in the clusters and used the first principle component as their environmental values. We matched the direction of the first principle component to that of the raw questionnaire data included in individual clusters. The cluster scores were standardized to a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. Finally, we excluded the outliers whose first principle component were outside of three standard deviations from the mean. The clustering of questionnaires for environmental factors in the replication cohorts was described in the Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Table 4.

Disease statuses used for the phenome-wide association study

In addition to the nine disease statuses used in the main analyses, we defined disease statuses based on ICD-10 in UKB1 and past medical history in BBJ1, as summarized in Supplementary Table 19. For the complications of diabetes mellitus (diabetic nephropathy and retinopathy), we restricted cases and controls to the T2D patients. We tested G×E interactions for the diseases with more than 1,000 cases in individual cohorts. Consequently, we tested 35 diseases for 49 lead variants in UKB1 and 52 diseases for 38 lead variants in BBJ1.

Metabolites measurement

We started from the internally quality controlled Nightingale NMR metabolome measurement data and removed its technical variation using the ukbnmr R package70. Briefly, this package removed the technical variation derived from: (1) the elapsed time from sample preparation to measurement, (2) the position (row and column) of the 96-well plate and (3) a series of measurement dates for each spectrometer. This package also calculated 76 useful biomarkers based on the ratio between directly measured ones, in addition to 249 biomarkers provided by Nightingale NMR (325 biomarkers in total; Supplementary Table 28). We then removed participants aged <18 or >85, or whose measured values were outside of three times the interquartile range (upper or lower quartile) or outside of three standard deviations from the mean. We also removed the following participants for particular biomarkers: participants with renal insufficiency (eGFR < 15 ml min–1 per 1.73 m2) for creatinine; participants with liver diseases, haematological malignancies, nephrotic syndrome or autoimmune diseases for albumin; or participants with diabetes mellitus for glucose and participants with autoimmune diseases for glycoprotein acetyls. We applied natural log transformation to the measurement values and standardized them to mean of 0 and s.d. of 1.

Protein expression measurement

We used the normalized Olink protein expression data (Olink Explore 3072). As implemented by Olink, these data were already bridge-normalized across measurement batches into the unit of normalized protein expression. As we did for other quantitative phenotypes, we removed participants aged <18 or >85, or whose measured values were outside of three times the interquartile range (upper or lower quartile), or outside of three standard deviations from the mean. We used 2,923 proteins with valid measurement data for both BBJ1 and UKB1 (Supplementary Table 27).

G×E interaction testing

All statistical tests were two-sided unless otherwise noted. As phenotypes, we targeted quantitative traits (clinical biomarkers, metabolites, and protein expression measurements), dichotomous traits (disease statuses), and time-to-event traits (disease onset for incidental cases and overall survival). For quantitative and dichotomous traits, we tested G×E interactions using GEM, a fast and scalable implementation of linear and logistic regressions with G×E interaction terms22 (Extended Data Fig. 1). We estimated the model-robust ‘sandwich’ standard errors to suppress the inflation of statistics22. As the case–control imbalance can cause the inflation of test statistics in the logistic regression, we re-estimated the effect sizes and P values using Firth logistic regression for the variants with P values <5.0 × 10−8 for dichotomous traits. For the time-to-event traits, we employed the Cox proportional hazard model implemented in the ‘survival’ R package. Individuals who had already developed the target disease at baseline or developed it within six months from baseline were excluded from the incidental case analyses.

We tested G×E interactions for different sets of environmental factors, as shown in Extended Data Fig. 1, and then aggregated P values across environmental sets on the Cauchy distribution23 to obtain per-variant P values. When P values were 0 (meaning that P values were <1.0 × 10−300), we estimated the precise P values using the multiple-precision floating-point arithmetic with the maximal precision of 10,000 bits, implemented in the Rmpfr R package. Regional G×E interactions were plotted using LocusZoom71. We defined a G×E interaction as significant at the variant level if the aggregated P value was below the genome-wide threshold of 5.0 × 10−8. We also reported the study-wide Bonferroni threshold for full transparency. We did not require that any individual environment’s interaction term be significant on its own, considering that G×E interactions can be driven by multiple environments. Nevertheless, we note that at least one raw P value was smaller than the Cauchy-combined P value in principle, as the Cauchy combination method is not a meta-analysis but rather returns a P value within the range of raw P values.

After evaluating the significance of G×E interactions at the variant level, we determined the order of importance of G×E interaction terms by backward elimination from the regression model with all G×E interaction terms. Specifically, we repeatedly removed the G×E interaction term with the least improvement in the likelihood of the linear regression model or the largest Wald P value of the Firth logistic regression model. After removing all G×E interaction terms, we brought back the G×E interaction terms one by one in the order of their importance if the model fit was improved with a P value less than 0.05 (likelihood ratio test). We considered that the environmental factors contributed to G×E interactions if the corresponding interaction terms were included in the final model. In principle, this approach selects more parsimonious sets of environments than the Akaike information criterion and can determine the top environment contributing to individual G×E interactions.

We used the first 20 genetic principal components, genotype array, age2, age × sex and age2 × sex as covariates for the UKB. For the other cohorts, we used the first ten principle components, age2, age × sex and age2 × sex as covariates. Age and sex, as well as other environmental factors, were included as the interaction terms with genotypes, and the variables used for interaction terms were automatically included as covariates. We also included the status of the target diseases in BBJ as covariates for quantitative traits and overall survival. We included the status of statin medication as an additional covariate for metabolome measurements. For sex-specific diseases in the phenome-wide association study, we excluded sex from the environmental factors and age × sex and age2 × sex from covariates.

Following that previous cross-population GWAS used the distance-based locus definition21, we defined that the genome-wide significant variants were in the same locus if their distance was less than 500 kbp. For the genome-wide G×E interaction tests on the proteome and metabolome, we first targeted 56 lead variants of clinical G×E interactions, including those identified by meta-analyses. We then extended the targets on the metabolome to (1) genotyped variants in each cohort, (2) HapMap3 variants and (3) the variants targeted by the meta-analysis across BBJ and UKB, to reduce the computational cost. After defining the metabolome G×E loci based on their distance as above, we merged the metabolome G×E loci if they overlapped with the same locus defined for the clinical traits. See Supplementary Methods for further methodological details.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Osaka (approval no. 734-18) and the ethics committee of the Graduate School of Medicine, the University of Tokyo (2023405G-(4)).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.