Animals

The experiments described in this study were conducted using adult male zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata; 120–500 days post-hatch). All procedures were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at UT Southwestern Medical Center.

Viral vectors

The following adeno-associated viral vectors were used in the experiments: rAAV2/9/fDIO–CBh–eGTACR1–mScarlet, rAAV2/9/CBh–Flippase, rAAV2/9/CBh–ChRmine–mScarlet, rAAV2/9/DIO–CAG–ChRmine–mScarlet, rAAV2/9/DIO–CAG–TeNT–mScarlet (Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center Neuroconnectivity Core at Baylor College of Medicine) and rAAV2/9/CMV–CRE–eGFP (Addgene). All viral vectors were aliquoted and stored at −80 °C until use.

Stereotaxic surgery

Aseptic stereotaxic surgeries were performed after birds were anaesthetized (isoflurane inhalation; 0.8%–1.5%).

Viral injections were performed using previously described procedures26,37,58. Briefly, a cocktail of adeno-associated viral vectors (rAAV/CBh–ChRmine in HVC, RA, area X or thalamus (2 µl per hemisphere); 1:2 of rAAV/CBh–FLP and rAAV/DIO–CBh–eGtACR1, respectively (1–2 µl total per hemisphere); rAAV/DIO–CAG–ChRmine in HVC or Uva (2 µl); rAAV/CMV–Cre in RA, area X or HVC (0.5–1 µl and 2 µl, respectively); rAAV/DIO–TeNT in HVC or Uva (2 µl); and rAAV/CMV–CRE in area X or HVC (2 µl), respectively) were injected (1 nl s−1) into target areas with a Nanoject III (Drummondsci) and glass capillaries. Experiments were conducted starting a minimum of 3 weeks after viral injections. Fluorophore-conjugated retrograde tracers (Dextran 10,000 MW, AlexaFluor 488, 568 and 647, Invitrogen; Fast Blue, Polysciences) were injected bilaterally into area X, RA or HVC (160 nl; 5 × 32 n, 32 nl s−1 every 30 s) (refs. 26,37,58). Electrophysiological mapping was used to determine the centres of HVC, NIf, mMAN, LMAN and RA, and area X, nucleus avalanche and Uva were identified using stereotaxic coordinates (coordinates relative to interaural zero: head angle, rostral–caudal, medial–lateral, dorsal–ventral (in mm). The stereotaxic coordinates were as follows: HVC (45°; anterior–posterior, 0; medial–lateral, ±2.4; dorsal–ventral, −0.2 to −0.6), NIf (45°; anterior–posterior, 1.75; medial–lateral, ±1.75; dorsal–ventral, −2.4 to −1.8), mMAN (20°; anterior–posterior, 5.1; medial–lateral, ±0.6; dorsal–ventral, −2.1 to −1.6), lMAN (20°; anterior–posterior, 5.1; medial–lateral, ±1.7; dorsal–ventral, −2.2 to −1.6), RA (80°; anterior–posterior, −1.5; medial–lateral, ±2.5; dorsal–ventral, −2.4 to −1.8), X (45°; anterior–posterior, 4.8; medial–lateral, ±1.6; dorsal–ventral, −3.3 to −2.7), nucleus avalanche (45°; anterior–posterior, 1.65; medial–lateral, ±2.0; dorsal–ventral, −0.9) and UVA (20°; anterior–posterior, 2.5; medial–lateral, ±1.6; dorsal–ventral, −4.8 to −4.2).

Optogenetic manipulations

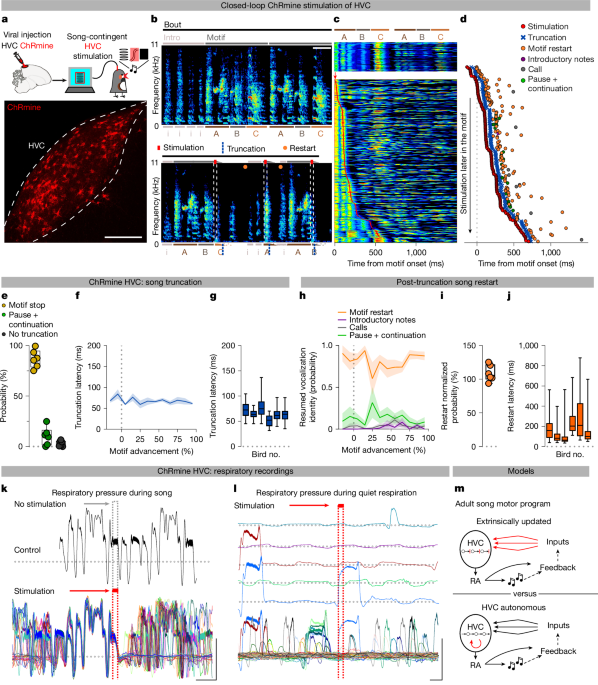

For optogenetic stimulation, optic fibres (multimode 400 µm; 0.39 numerical aperture; ThorLabs) were implanted bilaterally dorsal to HVC, RA, area X or Uva using acrylic glue and dental cement. Although the 400-µm-diameter fibres may not completely cover the entirety of the areas, we estimated that the cone of light could stimulate the vast majority of the targeted neurons. After recovery, the implanted fibres were connected to optic fibres through ceramic sleeves. The fibres were connected to a rotary joint and interfaced with a 1.5-mm multimode fibre connected to a light-emitting diode box (Prizmatix). Light intensity was regulated to achieve a final output of approximately 10 mW. We used a custom software (pcaf; LabVIEW) to deliver optogenetic stimulation during song (200 ms or 1 s for HVC afferent stimulation, 10–50 ms for direct ChRmine somatic stimulation and 50–200 ms for antidromic HVCX stimulation). In many instances, our goal was to target as many moments as possible within a bird song motif. To achieve this, we targeted most of the motifs birds were producing using quasi-random light onset delays introduced through a transistor–transistor logic. This targeting strategy allows for a detailed analysis of motif-level effects but limits our ability to conduct meaningful song-bout-level analysis of the behaviour. We note that light delivery over HVC or other brain regions is not sufficient to cause truncations or other disruptions in singing behaviour because several experiments using light stimulation (light stimulation of afferent pathways into HVC or of area X neurons) have no effect on singing behaviour. Air sac recordings and analysis were performed as previously published15.

Lesion quantification

Excitotoxic lesion was induced by 1% ibotenic acid (50–100 nl per injection site) or a cocktail of 1% ibotenic acid and 100 mM quisqualic acid (Uva and LMAN). Lesion extent was first verified by the absence or sparseness of NeuN immunostaining in the targeted nuclei. To provide an unbiased estimate of the lesion extent, retrograde tracers were injected in HVC and RA to highlight any surviving cells in the afferent nuclei. In control animals, the number of retrograde tracer-filled cells in each nucleus was quantified, and correlations were calculated between cell counts in each nucleus (Extended Data Fig. 6a–f). This analysis provided a statistical validation to extrapolate the number of cells in a target nucleus from the number of cells counted in a reference nucleus. Therefore, an average ratio across nuclei cell counts was calculated. On the basis of these control ratios and the number of cells in a non-lesioned reference nucleus, the expected number of retrogradely filled cells in each nucleus of each hemisphere was estimated.

In vivo extracellular recordings

To test the functional expression of opsins, we performed extracellular recording of HVC activity in birds under light isoflurane anaesthesia (0.8%) with Carbostar carbon electrodes (impedance: 1,670 µΩ cm; Kation Scientific). A 400-µm multimodal optical fibre was placed on the brain surface overlaying HVC and delivered light stimulation (470 nm; approximately 20 mW; 1 s) during neural recordings. To test antidromic excitation of HVCX neurons by axon terminal optical stimulation, optic fibres were implanted over area X (470 nm; approximately 20 mW; 100 ms). Signals were acquired at 10 kHz and band-pass filtered (300 Hz high-pass; 20 kHz low-pass). Spike rate (binned every 10 ms) and PSTHs were calculated to quantify light stimulation responses (one to five sites per hemisphere; Spike2). Birds without optically evoked responses were excluded from experiments. Spike counts and PSTHs were normalized to the pre-stimulus baseline (500 ms). Two-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) were calculated comparing the time course between stimulated and not stimulated recordings: for testing HVC afferents (1-s stimulation), 0–5 s (light stimulation; 0.5–1.5 s) versus 5–10 s (control; no stimulation); for ChRmine-expressing HVC neurons or HVC→area X stimulation (100-ms stimulation) 0.7–1.4 s (300 ms before and after 100-ms light stimulation) versus 5.7–6.4 s (control; no stimulation). Wilcoxon tests were performed on the average time course (with intervals specified in the figure legends).

Ex vivo physiology

Slice preparation

Zebra finches were deeply anaesthetized and then decapitated. The brain was removed from the skull and submerged in cold (1–4 °C) oxygenated dissection buffer. Acute sagittal 230-μm brain slices were cut in ice-cold carbogenated (95% O2/5% CO2) solution, containing 110 mM choline chloride, 25 mM glucose, 25 mM NaHCO3, 7 mM MgCl2, 11.6 mM ascorbic acid, 3.1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2.5 mM KCl, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4 and 0.5 mM CaCl2, and adjusted to 320–330 mOsm. Individual slices were incubated in a custom-made holding chamber filled with artificial cerebrospinal fluid, containing 126 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 26 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM d-(+)-glucose, 2 mM MgSO4 and 2 mM CaCl2, adjusted to 310 mOsm, pH 7.3–7.4 and aerated with a 95% O2/5% CO2 gas mixture. Slices were incubated at 36 °C for 20 min and then kept at room temperature for a minimum of 45 min before recordings.

Slice electrophysiological recording

The slices were constantly perfused in a submersion chamber with 32 °C oxygenated normal artificial cerebrospinal fluid. Patch pipettes were pulled to a final resistance of 3–5 MΩ from filamented borosilicate glass on a Sutter P-1000 horizontal puller. HVC projection neuron classes, as identified by retrograde tracers, were visualized by epifluorescence imaging using a water immersion objective (×40; 0.8 numerical aperture) on an upright Olympus BX51 WI microscope, with video-assisted infrared CCD camera (QImaging Rolera). Data were low-pass filtered (10 kHz) and acquired (10 kHz) (Axon MultiClamp 700B amplifier, Axon Digidata 1550B data acquisition and Clampex 10.6; Molecular Devices).

For voltage clamp whole-cell recordings, the internal solution contained 120 mM cesium methanesulfonate, 10 mM CsCl, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM EGTA, 5 mM creatine phosphate, 4 mM ATP–Mg and 0.4 mM GTP–Na (adjusted to pH 7.3–7.4 with CsOH). For current clamp recordings, the internal solution contained 116 mM K gluconate, 20 mM HEPES, 6 mM KCl, 2 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EGTA, 4 mM MgATP, 0.3 mM NaGTP and 10 mM Na phosphocreatine (adjusted to pH 7.3–7.4 with KOH; 299 mOsm).

Optically evoked synaptic currents were measured by delivering two light pulses (1 ms, spaced 50 ms, generated by a CoolLED pE-300) focused on the sample through the ×40 immersion objective. Sweeps were delivered every 10 s. Synaptic responses were monitored while holding the membrane voltage at −70 mV (for oEPSCs) and +10 mV (for optogenetically evoked inhibitory postsynaptic currents (oIPSCs)). We monitored different light stimulation intensities before baseline recording to achieve oEPSC responses at approximately 50% of the maximal response. Access resistance (10–30 MΩ) was monitored throughout the experiment, and recordings were discarded from further analysis if resistance changed by more than 20%. The excitation–inhibition (oEPSC/oIPSC) ratio was calculated by dividing the amplitude of the oEPSC at −70 mV by the amplitude of the oIPSC at +10 mV during identical light intensity stimulation. To validate inhibitory and excitatory post-synaptic currents as γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)ergic and glutamatergic, respectively, in a subset of cells the GABAa receptor antagonist SR 95531 hydrobromide (gabazine; 10 µM) was added to the bath while holding the cell at +10 mV, or the AMPA receptor antagonist 6,7-dinitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (10 µM) while holding the cell at −70 mV. In another subset of cells, once the baseline measures were established, we tested for monosynaptic connectivity by bath application of 1 µM TTX, followed by 100 µM 4-AP, and measured the amplitude of post-synaptic currents returning following 4-AP application. On the basis of the signal-to-noise ratio of the recordings, currents under 5 pA were considered unreliable and not considered further, as were currents rescued by 4-AP application with an amplitude less than 10 pA (non-monosynaptic; two instances: 1 HVCX→HVCX and 1 HVCX→HVCRA).

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Birds were anaesthetized with EUTHASOL (Virbac) and transcardially perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Free-floating sagittal sections (30 µm) were cut using a cryostat (Leica CM1950). These sections were first washed in PBS, then blocked in 3% bovine serum albumin in 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with primary antibodies (α-NeuN MAB377, Millipore, 1:500; α-GFP a11122, Invitrogen, 1:1,000) diluted in the blocking buffer at 4 °C for 24 h. The slices were washed with PBS and incubated at room temperature for 2 h with fluorescent secondary antibodies (Jackson 715-605-150 Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated donkey anti-mouse for NeuN and Millipore A21206 Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit for GFP), diluted in blocking buffer). After PBS wash, sections were mounted onto slides with Fluoromount-G (eBioscience). Composite images were acquired and stitched using an LSM 880 or LSM 710 laser scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss) and/or a ZEISS Axio Scan Z1 (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Whole Brain Microscopy Facility; RRID: SCR_017949). Image analyses were performed using ImageJ. After electrophysiological recordings, the slices were incubated in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Sections were then washed in PBS, mounted on glass slides with Fluoromount-G (eBioscience) and visualized under an LSM 880 laser scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss). In situ hybridization experiments were conducted as previously reported.

Three-dimensional brain imaging and processing

Imaging and processing of the sample brain with tracers injected in HVC (Alexa 488-conjugated dextran 10,000) and RA (Alexa 568-conjugated dextran 10,000) for three-dimensional (3D) rendering were conducted with the help of Denise Ramirez and Ariana Nawaby (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Whole Brain Microscopy Facility; RRID: SCR_017949). After perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde, the brain was embedded in oxidized agarose in preparation for sectioning. The TissueCyte 1000 instrument (TissueVision) automatically sectioned the entire volume of the brain at 100 mm in the coronal plane and collected mosaic image tiles encompassing each section. For preprocessing, images were downsampled to 1.5-μm xy resolution and colour contrast adjusted to provide high visual contrast between signals of interest and background.

For segmentation, a selected portion of signals of interest in the downsampled contrast adjusted images of the tissue was visually identified, annotated and used to train a random forest classifier for segmentation in ilastik (v.1.3.3) (refs. 61,62,63,64). This classifier was applied to all section images in the brain to assign a probability score to each pixel in the image, corresponding to its chance of belonging to specific fluorescent signals, autofluoresence or background noise. The total autofluorescence (Alexa 488 (green) and Alexa 568 (red)) pixelwise probability scores were further processed and used for visualization.

For segmentation post-processing, to create a grey silhouette of the overall shape of the brain, the autofluoresence probability signal was thresholded using the ImageJ default thresholding algorithm. Any holes in the binary mask were then flood-filled, and particles greater than 3,024 px2 were removed. Green and red probabilities were thresholded at 105 and 79 8-bit pixel intensities, respectively, as determined visually to reduce low-probability noise in the image. The GFP signal in the rostral-most portion of the brain (beyond section 135) was dimmed for better visibility of more caudal structures by subtracting the pixel intensities by 140 pixel intensity units in the 8-bit range.

For visualization, combined RGB images of the autofluoresence (grey), Alexa 488 (green) and Alexa 568 (red) post-processed probabilities were visualized in 3D using VAA3D software (v.V3.447; https://home.penglab.com/proj/vaa3d/home/index.html).

Song analysis

Birdsongs were recorded and analysed using Sound Analysis Pro (SAP) 2011 (ref. 65), and plots were made with a modified version of Avian Vocalization Network66. We manually measured and categorized the outcomes of optogenetic stimulations. Truncations were defined as stimulation-contingent atypical amplitude decays of 300 ms or less (not present in control motifs), visible as silent gaps in the spectrogram. Truncation latencies were measured from the onset of the light delivery to the onset of the optically contingent silent gap. Stop was defined as truncation not followed by continuation or resumption of the motif. Syllable boundaries and complex syllable elements were delimited by silent pauses or by clear spectral continuity changes. Twenty stimulated song segments were measured for stimulated and non-stimulated conditions for quantification of acoustic properties and sound similarity (SAP). Acoustic properties of the stimulated segment were measured and compared with the corresponding song fragment in unstimulated control motifs. When optical stimulation did not cause truncation, acoustic properties were calculated on the song fragment from the onset of optical stimulation to the end of the last syllable. The entire motif was analysed during 1-s stimulation trials.

In the 1-s time window after song truncation, optical stimulation effects were manually classified as falling into one of four categories: (1) motif reset (restarting with the first song syllable, with introductory notes or with syllables that normally link motifs); (2) calls (typical zebra finch calls); (3) introductory notes (those not followed by motif initiation); or (4) pause and continuation (post-truncation motif resumption at any syllable in the motif other than the first syllable). To calculate the normalized motif reset probability, the number of motifs per bout was calculated over 30–50 bouts (defined as chains of motifs, started with introductory notes and mostly uninterrupted; in rare occasions, we found motifs produced within 1 s from other motifs, and they were considered as part of the previous bout; M, average number of motifs per bout). Each bird’s probability of motif truncation was then normalized (normalized motif reset probability = motif reset probability/[1 − (1/M)), following the logic that 1/M is the likelihood of each motif to be the last in the bout and not be followed by another motif. Therefore, 1 − (1/M) is the probability of a motif to be followed by another motif in the current bout. The probability of reset implies the presence of a motif after the truncated one examined. Therefore, dividing by the likelihood of that motif being followed by another one returns a normalized measure of the reset.

To report cross-motif quantification of truncation or reset latency and resumed vocalization identity probability, events were categorized depending on the time point within the motif at which the onset of the corresponding stimulation occurred. The events were then grouped in 10% bins across the motif duration, per bird, to allow for comparison between birds with different motif lengths. Then 100% for each bird was set to the duration of the motif −100 ms, as the latency to truncation when applied later than 100 ms before the end of the motif would lead to unclear effects on the syllables (average truncation latency across groups = 74.36 ± 3.06). Whenever the stimulation happened in the last 100 ms of motif, the events were classified in the −20% to 0% bins, affecting the transition to the following motif (if any). Stimulations, truncations and post-truncation effects occurring during introductory notes and inter-motif connecting syllables were assigned to these −20% to 0% time bins on the basis of their temporal distance to the syllable A (if no syllable A onset was produced, the effects were not considered for further analysis, as we could not categorize the introductory note as produced at specific distance from the motif for the percentage computation).

To evaluate the likelihood of optogenetic inhibition or stimulation across a motif–motif transition to terminate a bout (Extended Data Fig. 4d–h), we delivered light or sham stimulation across the motif and extending beyond its end, and we quantified the probability of the stimulation to be contingent with the termination of the bout for 50 trials in each condition.

In lesion experiments, a minimum of 20 motifs were scored with SAP against pre-surgery motifs. Failed motif starts were defined as a series of introductory notes not leading to a motif. The number of motifs in a bout was counted over 50 bouts; for TeNT experiments, for birds that would ultimately lose their song (UVAHVC TeNT; some HVCX TeNT), the last 50 bouts before song cessation were analysed. In case of absence of motifs being produced post-lesion in Fig. 3b (the birds did not sing at all), the accuracy was assigned the value of 0 for the sake of classification.

Recurrent circuit model of HVC

The computational model used in this study is on the basis of a canonical recurrent circuit model (continuous attractor neural network67,68,69) and simulated in the BrainPy framework70. In a typical continuous attractor neural network, excitatory neurons are arranged to uniformly cover a linear feature space (for example, the location of the timing chain in the current case71) and have mutual interactions through recurrent connections72. This configuration gives rise to a continuous manifold that sustains a series of activity bumps. A song motif is considered to be controlled by an activity bump traversing from one end of the chain to another73.

To better reflect the biological characteristics of the songbird HVC, we introduced several specific features.

The model incorporates the following five distinct neuron types to capture the functional diversity in the songbird HVC:

-

(1)

Excitatory neurons (HVCRA, \({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{RA}}}\), and HVCX, \({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{X}}}\))

The excitatory neurons responsible for encoding the neural sequence are divided into two groups (HVCRA and HVCX), with their firing rates denoted as \({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{RA}}}\) and \({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{X}}}\), respectively. Consistent with experimental observations, the model only includes intergroup connections and leaves neurons within the same group unconnected. Simulations demonstrated that these intergroup connections are sufficient to self-sustain non-zero responses and moving sequences.

-

(2)

Global inhibitory neurons (\({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{g}}}\))

To keep the stability of the network, the network model contains a global inhibitory neuron with the firing rate \({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{g}}}\). Compared with excitatory neurons, in the model, this neuron has more rapid dynamics and a steeper activation function to provide effective global inhibition.

-

(3)

Local inhibitory neurons (\({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{I}}}\))

The circuit model has another group of inhibitory neurons (\({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{I}}}\)) providing local, structured inhibitory feedback to the excitatory populations, which is essential to generate spontaneous movement of the population activity bumps of excitatory neurons within the circuit. The \({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{I}}}\) bump slightly lags behind the excitatory neuron bumps owing to transmission delay and slow dynamics, so that the excitatory neurons at more distant locations will be suppressed less and build up more activity. As a result, the activity bump of excitatory neurons is ‘pushed’ to move forward.

-

(4)

Peri-song neurons (\({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{ps}}}\))

The circuit model contains an HVCRA peri-song neuron group (\({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{ps}}}\)) that is modelled to target HVCRA song neurons at the initial end of the manifold. This group plays a critical role in initiating and resetting motif generation.

Circuit dynamics

The neural dynamics underlying these activities are captured by a set of dynamic equations:

$${\tau }_{{\rm{E}}}{\dot{{\bf{r}}}}_{{\rm{R}}{\rm{A}}}=-{{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{R}}{\rm{A}}}+{W}_{{\rm{X}},{\rm{R}}{\rm{A}}}\cdot {f}_{{\rm{E}}}({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{X}}})+{W}_{{\rm{I}},{\rm{R}}{\rm{A}}}\cdot {f}_{{\rm{I}}}({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{I}}})+{w}_{{\rm{g}},{\rm{R}}{\rm{A}}}\,{f}_{{\rm{g}}}({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{g}}})+{W}_{{\rm{p}}{\rm{s}},{\rm{R}}{\rm{A}}}\,{f}_{{\rm{p}}{\rm{s}}}({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{p}}{\rm{s}}})+{I}_{{\rm{e}}{\rm{x}}{\rm{t}},1}$$

(11)

$${{\tau }_{{\rm{E}}}\dot{{\bf{r}}}}_{{\rm{X}}}=-{{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{X}}}+{W}_{{\rm{R}}{\rm{A}},{\rm{X}}}\cdot {f}_{{\rm{E}}}({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{R}}{\rm{A}}})+{W}_{{\rm{I}},{\rm{X}}}\cdot {f}_{{\rm{I}}}({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{I}}})+{w}_{{\rm{g}},{\rm{X}}}\,{f}_{{\rm{g}}}({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{g}}})+{I}_{{\rm{e}}{\rm{x}}{\rm{t}},2}$$

(12)

$${\dot{{\bf{r}}}}_{{\rm{g}}}=-{{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{g}}}+{[{W}_{{\rm{R}}{\rm{A}},{\rm{g}}}\cdot {f}_{{\rm{E}}}({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{R}}{\rm{A}}})+{W}_{{\rm{X}},{\rm{g}}}\cdot f}_{{\rm{E}}}({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{X}}})]$$

(1.3)

$${{\tau }_{{\rm{I}}}\dot{{\bf{r}}}}_{{\rm{I}}}=-{{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{I}}}+{[{{W}_{{\rm{R}}{\rm{A}},{\rm{I}}}\cdot f}_{{\rm{E}}}({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{R}}{\rm{A}}})+{W}_{{\rm{X}},{\rm{I}}}\cdot f}_{{\rm{E}}}({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{X}}})]$$

(1.4)

$${\tau }_{{\rm{p}}{\rm{s}}}{\dot{{\bf{r}}}}_{{\rm{p}}{\rm{s}}}=-{{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{p}}{\rm{s}}}+{I}_{{\rm{U}}{\rm{v}}{\rm{a}}}+{w}_{{\rm{g}},{\rm{p}}{\rm{s}}}\,{f}_{{\rm{g}}}\,({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{g}}})$$

(15)

In these equations, subscripts denote the neuron types. The parameter \(\tau \) represents the time constant, and \(f(\cdot )\) denotes the activation function for each neuron group. External input currents are denoted as \({I}_{\mathrm{ext}}\), and specific terms such as \({I}_{\mathrm{Uva}}\) correspond to input from Uva. The capital \({W}_{{\rm{A}},{\rm{B}}}\) indicates the connection matrix from group A to B with dimensions \({N}_{{\rm{B}}}\times {N}_{{\rm{A}}}\), where \(N\) is the number of neurons in the respective group, whereas the lowercase \(w\) indicates the scalar connection strength. For convenience, we set \({N}_{\mathrm{RA}}={N}_{{\rm{X}}}={N}_{{\rm{I}}}=N\) and \({N}_{{\rm{g}}}={N}_{\mathrm{ps}}=1\). Specifically, to support a continuous manifold, the entries of connections between excitatory and local inhibitory neurons are determined by the distance between the index of pre-synaptic and post-synaptic neurons:

$${W}_{{\rm{A}},{\rm{B}}}^{(ij)}={w}_{{\rm{A}},{\rm{B}}}\,\exp \left[-{\left(\frac{2{\rm{\pi }}}{N}\right)}^{2}\frac{{(i-j)}^{2}}{2{\sigma }^{2}}\right]$$

(2)

where \({w}_{{\rm{A}},{\rm{B}}}\) (\({\rm{A}},{\rm{B}}\in \{\mathrm{RA},{\rm{X}},{\rm{I}}\}\)) denotes the peak weight of the weight from neuronal population \({\rm{A}}\) to \({\rm{B}}\).

To target the peri-song output to the initial location of the manifold, \({W}_{\mathrm{ps},{\rm{E}}}\) is a \(N\times 1\) matrix with its column in a Gaussian profile centring at 0:

$${W}_{\mathrm{ps},{\rm{E}}}^{({\rm{k}})}={w}_{\mathrm{ps},{\rm{E}}}\,\exp \left[-{\left(\frac{2{\rm{\pi }}}{N}\right)}^{2}\frac{{(k-0)}^{2}}{2{\sigma }^{2}}\right]$$

(3)

Sequence initiation

The fundamental property of the network is its ability to spontaneously generate neural sequences. In our model, peri-song neurons initiate the sequential activity. The peri-song neurons receive excitatory input, probably originating from the upstream nucleus Uva, while simultaneously receiving inhibitory input from the global inhibitory neurons. When the network is silenced, whether at rest or following truncation, activity in the global inhibitory neuron decreases, which disinhibits the peri-song neurons. This release from inhibition then triggers the onset of a motif.

Boundaries

Following the activation of excitatory neurons, the activity bump is driven by locally structured inhibitory feedback from \({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{I}}}\) to traverse the continuous manifold. For the bump to gain a directional motion tendency, the inhibitory feedback is intentionally enhanced at the initial locations on the chain. Owing to the recurrent nature of the network, the bump would ordinarily ‘bounce’ back upon reaching the end of the chain. However, this behaviour is inconsistent with observed data. To address this, we introduced a fading mechanism for excitatory-to-excitatory connections as the bump approaches the boundary, simulating a ‘boundary effect’. This gradual reduction in connectivity causes the bump to diminish as it reaches the end point, resulting in an automatic cessation of activity that mimics the natural termination of a motif. These two boundary behaviours were implemented by multiplying the connection strength with a compensation factor:

$${{W}_{{\rm{I}},{\rm{R}}{\rm{A}}/{\rm{X}}}^{(ij)}}^{{\prime} }={W}_{{\rm{I}},{\rm{R}}{\rm{A}}/{\rm{X}}}^{(ij)}\,\left(1+{c}_{0}\,\exp \left[-{\left(\frac{2{\rm{\pi }}}{N}\right)}^{2}\frac{{i}^{2}}{4{\sigma }^{2}}\right]\right)$$

(41)

$${{W}_{{\rm{R}}{\rm{A}}/{\rm{X}},{\rm{X}}/{\rm{R}}{\rm{A}}}^{(ij)}}^{{\prime} }={W}_{{\rm{R}}{\rm{A}}/{\rm{X}},{\rm{X}}/{\rm{R}}{\rm{A}}}^{(ij)}\,\left(1-{c}_{1}\,\exp \left[-{\left(\frac{2{\rm{\pi }}}{N}\right)}^{2}\frac{{(i-N-\phi )}^{2}}{4{\sigma }^{2}}\right]\right)$$

(42)

\(\mathrm{where}\,\phi \) is an offset term, in which we take the value \(\phi =0.5\sigma N/2{\rm{\pi }}\). The compensated connection matrices are shown in Fig. 5c.

Truncation

To simulate optogenetic stimulation truncating HVC neuronal sequences observed in experimental studies, we applied an intense, spatially homogeneous pulse input to either HVCRA or HVCX neurons. Following this stimulation, both \({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{RA}}}\) and \({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{X}}}\) became hyper-activated, leading to rapid suppression by the fast response of \({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{g}}}\). These neurons remain suppressed until \({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{g}}}\) activity subsides, corresponding to the observed motif truncation (Fig. 5e,f). Subsequently, the peri-song neurons reinitiate the neural sequence, allowing the motif to resume from the beginning. Considering that HVCRA and HVCX are connected symmetrically in the current model, we only simulated optogenetic stimulation on HVCRA as a verification.

HVCX degradation

To simulate the effects of degradation of HVCX neuron neurotransmission, as observed in Fig. 5g,h, we manually modified the output projections of HVCX. Let \(p\) denote the proportion of degradation. Under this condition, the degraded projection from HVCX to HVCRA (\({W}_{{\rm{X}},\mathrm{RA}}{\prime} \)) can be expressed as

$${{W}_{{\rm{X}},{\rm{R}}{\rm{A}}}^{(ij)}}^{{\prime} }={[(1-p){W}_{{\rm{X}},{\rm{R}}{\rm{A}}}^{(ij)}+\sqrt{(1-p){W}_{{\rm{X}},{\rm{R}}{\rm{A}}}^{(ij)}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{W}}}{\xi }_{ij}]}_{+}$$

(5)

where \({W}_{{\rm{X}},\mathrm{RA}}^{({ij})}\) represents the original connection strength, \({\sigma }_{W}\) denotes the variation coefficient, \({\xi }_{{ij}}\) is an independent Gaussian noise term indexed by the pre-neuron and post-neuron indices ij, and \({[x]}_{+}=\max (x,0)\) denotes the negative rectification, ensuring the weight is always excitatory (positive).

During synaptic degradation over weeks, experiments revealed that neuronal sequences observed in different trials within the same day could traverse and then disappear at random locations on the chain. We assume that the synaptic weights within the same day are nearly the same, and that the random progression along the chain results from the variability of single neurons. Therefore, to reproduce the random progression along the chain during synaptic degradation, each HVCRA neuron \({{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{RA}}}(j)\) receives a Poisson-like noise \({I}_{\mathrm{noise}}\), mimicking stochastic spike generation:

$${I}_{{\rm{n}}{\rm{o}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{s}}{\rm{e}}}(j)=\sqrt{{F{\bf{r}}}_{{\rm{R}}{\rm{A}}}(j)}\xi (t)$$

(6)

where \(F\) is the Fano factor scaling the noise and \(\xi (t)\) is a standard Gaussian white noise. Moreover, the noises received by different neurons are independent of each other. Under these conditions, we observed that the sequences terminated at random positions. As illustrated in Fig. 5g, the average sequence length decreased as the proportion of neuronal degradation increased.

Statistical analysis

All data were analysed with GraphPad Prism 10. Data were tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk Test. Parametric and non-parametric statistical tests were used. To compare between two groups, t-test, Mann–Whitney and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests were used. For more than two conditions, one-way and two-way ANOVA or the Kruskal–Wallis test were performed. Cumulative probability curves were calculated for each animal and then tested in groups for statistical significance. Only one comparison among all groups was made to avoid repeatedly comparing the same dataset (HVC) with individual other datasets. Fisher or X2 tests, followed by Dunn’s post hoc test, were used to compare the probability of finding optically evoked responses across the HVC projection neuron classes while stimulating the different afferents. Dunn’s, Sidak’s or Holm–Sidak’s post hoc tests were used to correct for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance refers to *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

Statistics and reproducibility

Each experimental result was produced independently and/or by combining at least two separate cohorts with similar results (for example, Uva lesions/silencing in Fig. 3 and Extended Data Fig. 4, multi-nuclei lesions in Extended Data Fig. 6 and HVCX–TeNT experiments in Fig. 5 and Extended Data Fig. 13). Figures showing viral expression or lesion extent are broadly representative of each experimental group.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.