The Human Studies Facility is an unremarkable six-story red-brick building on the medical school campus of the University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill. But for 30 years, this laboratory, run by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), led the world in investigating respiratory hazards.

Its scientists used nine human exposure chambers to prove cause and effect between pollutants and health outcomes. Their work informed air-pollution policy not only in the United States, but also around the world.

On 30 June, however, the facility shut its doors after the US government refused to renew its long-standing lease with the university. This is a significant loss, and comes at a crucial moment for respiratory health, says Robert Devlin, a former senior EPA scientist who worked at the lab throughout its 30-year run. Without the facility, Devlin says, there will be no way to find out whether current air-quality standards are safe and protective. “We’ll no longer be able to answer the question.”

Nature Outlook: Lung health

An EPA spokesperson declined to answer Nature’s questions and instead stated that “all of the functions from this lab are in the process of or have been transferred” to another EPA facility in nearby Research Triangle Park, and that Nature’s sources “seem to be grossly misinformed”. Devlin says that such a move is impossible. The facility’s exposure chambers alone occupy around 1,860 square metres and require specialized engineers to maintain. “The exposure facility is unique and is not able to be transferred,” Devlin says. “To be blunt, they are lying.”

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that air pollution causes 7 million premature deaths each year, globally. Actions to improve air quality have saved lives. In the United States, for example, research1 suggests that annual deaths attributed to air pollution almost halved between 1990 and 2010, from 135,000 to 71,000. In 43 European countries, air-pollution deaths dropped by 42% between 1990 and 2019, from an estimated 639,000 to 368,0002. But in the United States, an alarming trend is emerging. For the first time in decades, concentrations of fine-particulate pollution have stopped declining in many places3. And in some areas, they are rising. According to a report (see go.nature.com/4oaolv7) released in April 2025 by the American Lung Association, nearly half of people in the United States now live with unsafe levels of air pollution. “The severity of the problem and abruptness of the change are unprecedented,” the authors of the report write. That trend will continue, specialists such as Devlin say, if the administration of President Donald Trump moves forward with its plans to roll back environmental regulations and to increase the use of fossil fuels.

Some of the threats to lung health come from well-known air pollutants such as ozone and particulate matter generated by vehicles. But a suite of emerging respiratory hazards — including increasingly intense wildfires, spore-spread fungal diseases and airborne microplastic — is adding urgency to the issue. Many of these hazards are poorly understood, and the harm that they cause seems to be worse when combined with other stressors, such as extreme heat. “It’s a double whammy,” says Mary Rice, a pulmonary physician and environmental-health researcher at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The closure of the Human Studies Facility is not the only way in which US scientists are being hampered in their effort to investigate and respond to these emerging hazards, Devlin says. In July, the Trump administration announced that the EPA’s entire research branch, the Office of Research and Development (ORD), would be dissolved. The EPA spokesperson said that this restructuring would “improve the effectiveness and efficiency of EPA operations” and “allow EPA to prioritize research and science more than ever before.” Although the agency has announced its intention to create a new Office of Applied Science and Environmental Solutions, this will report directly to the EPA administrator, which was not the case previously. “The big concern is that this EPA administrator intends to be very active in setting the scientific agenda”, Devlin says.

Scientists have been left scrambling to fill knowledge gaps and prepare for the future. “We need to understand what the threats are and also what we can actually do to protect people,” says Ilona Jaspers, an inhalation toxicologist at the UNC at Chapel Hill. But without government grants and support, the large, multi-site studies needed to do this will not be feasible, she says. “We are losing the capabilities and infrastructure to prepare.”

Heterogenous hazard

With temperatures rising, the frequency of large, destructive wildfires around the world has more than doubled over the past two decades. Many of those fires occurred in the forests of the western United States and Canada, which saw an 11-fold increase in extreme fires from 2003 to 20234. Although the fires themselves can cause catastrophic damage, the resulting smoke also poses a major danger. “This is uncharted territory, and we’re all trying to figure out the health effects,” says Steven Davis, an Earth-system scientist at Stanford University in California.

Understanding the impact of wildfires is challenging because smoke is not a single pollutant, but rather a complex and highly variable mixture. “It’s not like a wildfire is a wildfire is a wildfire,” Jaspers says. Its composition of noxious gases, particulate matter, toxic metals and more depends on an assortment of variables, including the temperature of the fire, the type of vegetation that burns, whether human-made structures are involved and the distance that the smoke travels before it reaches human populations. Aerosols in the atmosphere are affected by ultraviolet light and by other chemicals in ways that generally make them more toxic.

Some impacts are already apparent. In a study published5 in September, Davis and his colleagues suggest that exposure to particulate matter from Canada’s 2023 wildfires killed 82,000 people around the world. A team led by Marshall Burke, an economist at Stanford University, estimated6 that US wildfires between 2011 and 2020 contributed to around 40,000 excess deaths from particulate-matter inhalation every year. By 2050, the researchers anticipate that there will be some 71,000 excess deaths. When they calculated the economic impacts of those deaths, they found that smoke exposure is “by far the single largest overall climate threat in the United States”, Burke says.

Exactly how and to what extent wildfire smoke contributes to illness and death is still poorly understood, says Daniel Costa, a toxicologist at UNC at Chapel Hill and a former research director at the EPA. But the details that have emerged are concerning.

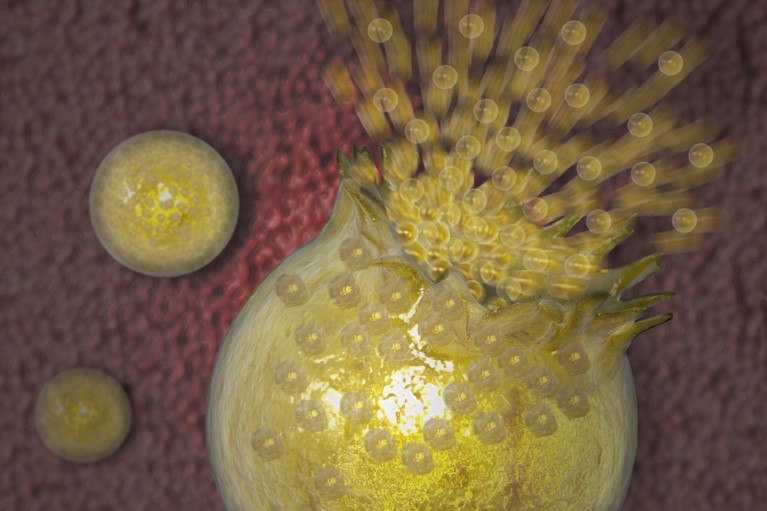

Illustration depicting a Valley Fever spherule bursting inside the lungs. Valley fever (Coccidioidomycosis) is a fungal disease endemic to certain parts of the American Southwest. It can lie dormant during long dry spells, then develop as a mould which breaks off into airborne spores. Once inhaled, the spores grow into spherules which continue to enlarge until they burst as shown. Hundreds of endospores are released, each of which can grow into a new spherule, further spreading the disease.Credit: Carol and Mike Werner / Science Photo Library

In a study7 of more than two million people in Canada, for example, researchers found that wildfire-smoke exposure was associated with a higher incidence of lung cancer and brain tumours. It has also been linked to a greater number of hospitalizations for asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), stroke and heart problems. Another study found a correlation between wildfire-smoke exposure and worse attention and decision-making8. “This could not only influence downwind communities, but could also affect firefighters’ abilities to fight fire and stay safe,” says Luke Montrose, an environmental toxicologist at Colorado State University in Fort Collins.

The harms of wildfire smoke can also be amplified through ‘co-exposure’. Extreme heat combined with wildfire smoke, for example, correlates with significantly more cardiorespiratory hospitalizations, especially for people from lower-income communities, than either hazard alone9. Individuals from those communities could bear disproportionate impacts, says Joan Casey, an environmental epidemiologist at the University of Washington in Seattle. Their homes might not be well sealed, and even if they are, people on lower incomes are more likely to have to leave home for work.

Stress might also make some people more susceptible to the health impacts of pollutants such as wildfire smoke. Devlin and his colleagues have shown, for example, that people exposed to the same level of pollution have an increased risk of a heart attack if they live in a socioeconomically disadvantaged neighbourhood — even after the data were adjusted for age, sex, race and smoking10. In an unpublished study, Jaspers found a correlation between biological markers of stress and a person’s reaction to wood-smoke exposure. “We’re all handling stress in different ways,” she says, and those differences “might affect how we respond to emerging pollutants”.

Natural hazards

Climate change also affects lung health by increasing other natural airborne hazards. These include sand and dust, and certain allergens such as pollen, which can trigger hay fever and asthma. Fungal diseases are also on the rise, says Bridget Barker, a biologist at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff. This increase stems, in part, from an expanded range of some fungi owing to climate change. Some fungal species are also evolving tolerance to higher temperatures, Barker says, making them more likely to thrive at the temperature of the human body. In 2022, the WHO launched a global effort to prioritize research-and-development needs for fungal pathogens, and issued a list of 19 such pathogens ranked according to their threat to public health.

One of the leading emerging fungal threats are Coccidioides spp., which cause Valley fever if inhaled. The pathogens are endemic to the western United States and parts of Central and South America. Around 5% of infected people develop severe disease. In Arizona, which has long been a Valley-fever hot spot, incidence has surged. The state reported nearly 11,000 cases in 2023 — an increase of more than 80% since 2013.

The prolonged droughts driven by climate change are creating optimal conditions for the soil-bound spores to become airborne. Researchers predict that, by 2100, the disease’s endemic range will more than double in size, and that 50% more people will be infected every year than in 200711. The disease has already begun to spread, appearing in northern California, Oregon and Washington from 2010. In anticipation of further spread, Barker and her colleagues are developing antifungal treatments for Valley fever, and a vaccine.

Pulmonary plastic

Unlike wildfires, fungi and allergens, plastic pollution is created entirely by humans. Research over the past few years has revealed the pervasiveness of micrometre and nanometre-sized plastic in the environment, and in the bodies of humans and other animals. Plastic found in the lungs of people after they have died suggests that particles are present in the air, and that inhalation is a major route of exposure, says Phoebe Stapleton, a toxicologist at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey.

Like wildfire smoke, plastic pollution is varied. It can contain any of some 16,000 chemicals, more than 4,200 of which are known to be highly hazardous to humans. Once in the lungs, plastic particles can be mistaken for bacteria or viruses by the immune system, triggering inflammation. Nanometre-sized particles can also find their way into the blood and lymph fluid. “From there, they can go anywhere in the body,” Stapleton says.

Studies of the health effects of these pollutants have produced worrying results. Leached chemicals from nylon microfibres interfere with the development of human and mouse lung epithelial cells. In a study published12 in November, Stapleton and her colleagues found that pregnant mice that inhaled nylon particles gave birth to offspring with life-long cardiovascular impairments.

Chris Carlsten, a physician and respiratory-medicine scientist at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, is planning to test the effects of inhaled microplastics in volunteers using an exposure chamber — one of only a few in existence, now that the EPA facility has closed. If researchers can identify the most harmful chemicals, then a convincing case could be made for the industry to stop using them. “It’s important to identify what they might be before it’s too late,” Stapleton says, “because the doses we’re being exposed to are increasing exponentially.”

Future forecast

Environmental threats to respiratory health cannot be entirely prevented. Forests will continue to burn, fungi will spread to new places and plastic will find its way into the environment. Scientists are, therefore, looking for ways to mitigate the impact. Some solutions might be straightforward. Burke and his colleagues found, for example, that air pollution inside homes can vary by as much as 20-fold between neighbouring houses13. Burke suspects there is a simple explanation for this: some people leave their windows open, whereas others keep their homes sealed, and might also be running air filters.

If this hypothesis bears out, the next step, Burke says, will be public education and finding ways to help everyone to access air filters, which can be costly. Government programmes could help, and Carlsten thinks that this would be a prudent economic choice: he and his colleagues have shown that partial government rebates for air filters would be a cost-effective way to reduce rates of asthma caused by wildfire smoke14.

As scientists learn more, Casey says, the hope is that policymakers will respond with laws and regulations to protect people and address the underlying drivers of respiratory threats. In the United States, however, specialists say that they see little sign of that happening. For example, regulations under the Clean Air Act do not currently apply to wildfires, because the EPA classifies them as exceptional events, and those can be excluded from air-quality requirements. “We have a rapidly growing source of air pollution that our main policy tool is not equipped to deal with,” Burke says. Further to losing its scientific research arm, the EPA is also rolling back regulations that affect air quality, Rice adds. “The agency seems to be shifting priorities away from its mission to protect human health and the environment in favour of industry priorities.”

The United States has been a global leader in regulating air quality for more than half a century, says Burke — and as a result has had better air quality than many other high-income countries, including many of those in Europe. With regard to the research needed to support regulations, however, it is unclear whether the European Union or anywhere else will “pick up the slack if we drop the ball here”, he says.

The data resoundingly indicate, however, that policymakers would be wise to invest in respiratory health, Davis says. He and his colleagues found that decarbonizing California’s energy system would result in health-related savings that would cover the entire cost of the transition for the state15. “You don’t even need to think about the climate,” Davis says. “It’s a huge opportunity to clean up our air.”