You have full access to this article via your institution.

Driverless cars rely on sensors that both perceive and respond to their surroundings.Credit: Patrick T. Fallon/AFP/Getty

What do wearable technologies have in common with driverless cars? And what do observatories peering into outer space have in common with laboratories studying the deepest oceans?

A sense of home

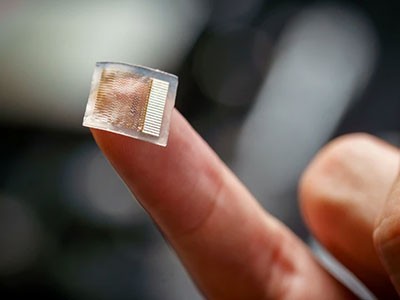

All use sensing technologies that perceive and respond to their surroundings. There are myriad sensors for detecting electrical signals, motion, pressure, temperature, force, gradients, fingerprints, chemicals and more. Sensor technologies are embedded in our lives, playing a central part in the function of everyday items — mobile phones, smart televisions, induction hobs and smoke detectors, to name but a few. Think of a piece of technology, and there are probably one or more sensors involved. Several estimates suggest that the global market for sensor technologies will exceed US$500 billion within a decade.

This is a field on the move, and now it has a new journal. Earlier this month, Nature Sensors launched with a mission1 to “convene the global sensing research community to advance discovery, enable real-world impacts and foster a shared scientific home for sensing research”.

From simple devices such as the mercury thermometer to super-sensitive instruments such as the laser interferometer LIGO, sensors have a long history. So why does such an established community need convening? The answer lies in the sheer diversity of the sensing technologies that are at the heart of many innovations and scientific discoveries.

The evolution of science and technology over the past century has been, by some measures, a story of division: the splitting of unitary fields into subfields, and the further subdivision of those subfields into even more specialized disciplines. In the case of sensors, we are, in some ways, seeing the opposite.

AI and the rise of intelligent sensing

The ‘home’ discipline for sensors, especially in universities, has conventionally been signal processing, which is a branch of electrical and electronic engineering. But today, sensor research incorporates knowledge and methods from across the biological and chemical sciences, as well as the physical sciences, engineering and technology. Its success depends on productive interdisciplinary working.

The editors of Nature Sensors aim to “connect communities and break down siloes”, and foster a shared sense of purpose across disciplines. The journal will publish primary research, along with news, opinion and analysis from across the field, and will also hold virtual and in-person events. The first of these will be in Seoul on 13 April, focused on the future of sensing technologies (see go.nature.com/4qpivuc).

Artificial intelligence will be central to that future, as a Feature in the launch issue of Nature Sensors shows2. Among the examples described is a project that aims to assist physicians in tracking the rehabilitation of patients who have had throat surgery3. Participants wore sensors that measured variables including vibration and electrical muscle signals. Huanyu Cheng at Pennsylvania State University in University Park and his colleagues found that AI did a better job of organizing and classifying this information than conventional data-processing methods did.

In another example, Aydogan Ozcan and his colleagues at the University of California, Los Angeles, improved the resolution of microscopes without physically adapting them. The authors trained an AI model on low- and high-resolution versions of images of tissue samples. After training, low-resolution images could be fed into the model, and it produced higher-resolution versions4.

How to reduce the environmental impact of wearable health-care devices

But, as the capabilities and applications of sensors grow, so will their environmental impact. Worldwide, more than 60 million tonnes of electronic waste is generated a year. Some of this will contain sensors. Little more than one-fifth of the waste is collected and recycled responsibly, according to a United Nations report (see go.nature.com/4rgigbb).

To get a sense of the impact of just one sector, environmental scientist Chuanwang Yang at the University of Chicago in Illinois and his colleagues projected that the ecological footprint of wearable health devices, namely monitors for glucose, blood pressure and heartbeat, will amount to the equivalent of 3.4 million tonnes of carbon dioxide by 2050. They also found that the devices’ complex miniaturized designs make collection and recycling difficult5. Ways to address waste are sorely needed, and must be a prominent focus for those working with sensors.

How can researchers from across disciplines better work together to address such challenges and find common solutions? Shared goals offer one point of convergence, as do joint projects and publications. “We need global efforts instead of individual labs or companies driving the field,” says Sami Haddadin, an electrical engineer at Mohamed bin Zayed University of Artificial Intelligence in Abu Dhabi2. His work in the field of AI sensing and robotics is discussed in the Feature in the launch issue.

The editors of Nature Sensors hope to play their part in bringing the community together and driving the necessary global conversations. We wish them every bit of good fortune in their mission to support scientifically sound and socially responsible innovation.