Animal handling and maintenance

The strains used in this study are shown in Supplementary Table 1. C. elegans and P. pacificus were maintained at 20 °C on nematode growth medium (NGM) agar plates containing Escherichia coli OP50.

Transgenic animals

To generate the Ppa-myo-2p::RFP (JWL27) strain, we used the previously established protocol61. This construct was generated by PCR amplification of a 1,231-base pair (bp) upstream region in front of the first predicted ATG start codon of Ppa-myo-2 and subsequent cloning into the pZH009 containing the codon-optimized red fluorescent protein (TurboRFP) plasmid. NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly Master Mix (New England Biolabs) was employed to perform cloning. To generate the transcriptional reporters of Ppa-tdc-1, Ppa-ser-3, Ppa-ser-6 and Ppa-lgc-55, we cloned the upstream regions before their predicted start codon, including: Ppa-tdc-1: 1,585 bp, Ppa-ser-3: 1,996 bp, Ppa-ser-6: 1,996 bp and Ppa-lgc-55: 1,917 bp, to drive expression of the codon-optimized TurboRFP or GFP as required. Each injection mix contained 10 ng µl−1 of the PstI-HF-digested reporter plasmids, 10 ng µl−1 of the PstI-HF-digested Ppa-egl-20p::GFP plasmid as co-injection marker and 60 ng µl−1 of the PstI-HF-digested P. pacificus genomic carrier DNA. The mix was injected in the gonads of young adults. Between 50 and 3,000 animals were injected depending on the strain. The transgenic animals were screened using an epifluorescence microscope (Axio Zoom V16; Zeiss). The fluorescence images of the transgenic animals were obtained using a Leica SP8 confocal microscope.

Transgenic line integration

Ppa-myo-2p::RFP was integrated into the P. pacificus genome as previously described62. Briefly, ten NGM plates each containing 20 fluorescent Ppa-myo-2p::RFP animals were exposed to ultraviolet irradiation at 0.050 J cm−2 using a UVP Crosslinker (CL-3000 Analytik Jena). After 3–4 days F1 fluorescent animals were singled out onto 120 individual culture plates and after another 3–4 days the F2 progeny were screened for possible integration events. This was detected by observing an increase in the number of fluorescent animals to ≥75% of the population. Individual animals from these plates were isolated and screened for consistent 100% transmission. Integrated lines were subsequently outcrossed 4× to remove potential mutations caused by ultraviolet exposure.

Behavioural imaging

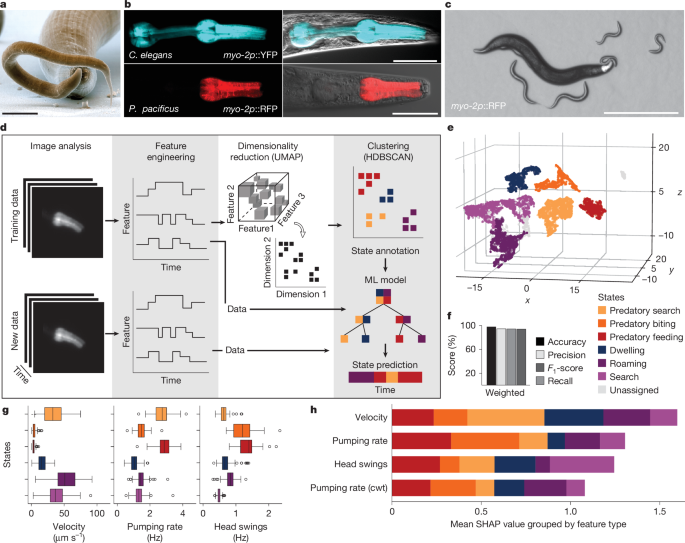

Ppa-myo-2p::RFP animals were recorded at ×1 effective magnification using an epifluorescence microscope (Axio Zoom V16; Zeiss) as previously described19. Recordings were made through a Basler camera (acA3088-57um; BASLER) with 15-ms exposure time. Animals were imaged at 30 frames per second for 10 min unless otherwise indicated. All animals that were in the field-of-view for at least 60 s were included in the analysis.

For tracking of animals on predatory assays, C. elegans prey were first maintained on OP50 bacteria until freshly starved, resulting in an abundance of young larvae. These plates were washed with M9, passed through two 20-µm filters, centrifuged and deposited onto the assay plate by pipetting 4 µl of worm pellet onto a 6-cm NGM unseeded plate. A copper arena (1.5 × 1.5 cm2) was placed in the middle of the assay plate to constrain predators in the recording field. Forty young adult P. pacificus predators (eurystomatous mouth form) were starved for 2 h and then added to assay plates inside the arena. After a recovery period of 15 min on the assay plate, their behaviours were recorded for 10 min.

For tracking of animals on bacterial assays, 300 µl of E. coli OP50 overnight culture was spotted onto an empty 6-cm NGM plate 24 h before the assay. A copper arena (1.5 × 1.5 cm2) was placed in the middle of the assay plate to contain the P. pacificus in the recording field. Forty young adult predators were starved for 2 h and then added to assay plates inside the arena. After a recovery period of 15 min on the assay plate their behaviours were recorded for 10 min.

Automated behavioural tracking

Animals were tracked using the custom Python analysis package ‘PharaGlow’19. PharaGlow performs a three-step analysis: (1) centre of mass (CMS) tracking and collision detection; (2) linking detected objects to trajectories; and (3) extracting centreline, contour, width and other parameters of the shape to allow extracting pharyngeal pumping events. The generated files contain the position and the straightened images which are further processed to extract the behavioural measures. Post-processing was applied according to ref. 19 with minor modifications. To obtain pumping traces from straightened animals, the inverted skew of intensity is calculated for each frame per animal (Fig. 1c). This metric is sensitive to the opening of the pharyngeal lumen and pharyngeal contractions. Peaks in the resulting trace correspond to pumping events.

Feature engineering

Videos of animals with labelled pharyngeal muscles were processed using PharaGlow19, which provided a set of initial behavioural features (CMS coordinates, the centreline, the pumping rate and the skew of the fluorescence intensity distribution, which relates to pumping contractions). From these basic features, we calculated two derived features. Using the CMS coordinates (x(t), y(t)), velocity was calculated with a time shift of dt = 60 frames (2 s). To obtain a description of head motion, we calculated the angle between the movement direction of the CMS and nose tip as

$$\theta =\arccos ({{\bf{v}}}_{\mathrm{CL}}{{\bf{v}}}_{\mathrm{CMS}})$$

where \({{\bf{v}}}_{{\rm{CL}}}\) is the unit vector of the centreline between the 1st and 5th coordinates along the 100 equidistantly sampled points of the centreline and \({{\bf{v}}}_{{\rm{CMS}}}\) is the unit vector of the CMS coordinates between two consecutive frames. To capture frequency changes in these features, we apply a wavelet transform using pywt with a gaus5 wavelet and extract the maximum frequency for each feature over time. The head angle and the skew which relates to the faster pumping motion were transformed with the following range of pseudo-frequencies (0.3–5.0 Hz). From the wavelet transformations the maximum frequency was extracted and included as a feature. Only for skew, two wavelet transforms from scale 11.2 and 3.8 were directly included additionally, which translates to pseudo-frequencies of about 1.3 and about 3.9 Hz, frequencies relevant for feeding behaviour. For velocity only one wavelet transform with the scale 18.7 was included, which translates to around 0.8 Hz. This transformation resulted in a total set of nine features.

Data curation

During recordings with many animals, a small subset of frames include overlapping animals. We detect and remove these instances in the data by removing frames with an area higher than 1.5 times the mean area in one recording.

Manual annotation

An expert human annotator generated labels for a subset of frames following the naming conventions for behaviour in ref. 16. Using LabelStudio pumping rate and velocity data were shown, and the annotator marked sequences corresponding to ‘biting’, ‘feeding’, ‘exploration’ or ‘quiescence’. The labels were verified by playing the corresponding video of the animal. For the unlabelled recordings, we automatically set labels encoding the recording condition, namely ‘on OP50’ or ‘on C. elegans larvae’. For preprocessing, the original features were preprocessed and downsampled before analysis using the following pipeline implemented in sklearn. First, further lagged features were created from the base features (velocity, instantaneous pumping rate, head angle, mean pumping rate) by shifting the individual dataset by 5, 10 and 15 frames (with 30 frames per second) forward or backward in time. This allowed us to include a short history in an otherwise memory-less pipeline. Subsequently, features were averaged using a rolling window of 30 frames (1 s) and downsampled to 1 frame per second. Labels were downsampled by using the modal value within 30 frames (1 s). The first and last seconds of each recording were truncated to eliminate effects of smoothing artifacts. The data were then transformed with a Yeo–Johnson power transform to improve normality and normalized with robust scaling. The entire pipeline was fitted on the training dataset and also applied during prediction of new data. For dimensionality reduction and clustering, the preprocessed training data with n = 106 animals from WT recordings on larvae and bacteria were embedded in three dimensions using UMAP (umap module, Python), using the parameters: n_neighbors = 70, min_dist = 0, repulsion_strength = 4, negative_sample_rate = 15, disconnection_distance = 0.85, n_components = 3. The resulting embedding was clustered with HDBSCAN. The number of clusters was determined using a silhouette score. To assign human-interpretable behavioural states to the clusters, the overlap between clusters and manual labels was calculated (Extended Data Fig. 2c) and cluster labels were verified by inspecting the feature distributions within the different clusters. Finally, cluster labels were spot-checked using the video data.

Behavioural state classification

Behavioural feature data with cluster labels found by embedding and clustering were used to train an XGBoost Classifier on the preprocessed data. Of the 106 videos, 9 were held-out as a test set and were not used for training the classifier. These videos were selected for their similarity in label distribution compared with the training set. Bayesian optimization was used to find optimal hyperparameters for the classifier using cross-validation. Training data were split using a stratified group shuffle split, whereby each recording was constituting a group. After the best hyperparameters were found, a model was trained on the complete training data using the optimal hyperparameters. Next, the performance of the model was evaluated with the prediction of the test set in comparison with the cluster labels. For this, standard model performance metrics were calculated (Fig. 1 and Extended Data Fig. 3a). Before prediction, the steps feature engineering and preprocessing are applied to the new data. To ensure reliability of the predictions, predictions with a probability of less than 50% were set to ‘None’. This threshold balances the rate of false-positive detections with the number of unlabelled frames. In our case, excepting frames at the start and end of each recording which were excluded because of filtering effects, this threshold resulted in only 1.2% of all frames classified as ‘None’.

Cluster validation

To validate the robustness of the identified behavioural states, the same pipeline was applied to an independent dataset, with n = 254 animals. The dataset was resampled to contain the same number of frames from worms recorded on larvae and on OP50 as the original training set. For dimensionality reduction the same parameters were used as previously described.

Dual-colour epifluorescence microscope behavioural tracking

To investigate predator–prey interaction, we recorded P. pacificus predators expressing the Ppa-myo-2p::RFP (JWL27) pharyngeal marker interacting with C. elegans larvae expressing Cel-myo-3p::GFP (SJ4103). Freshly starved plates of Cel-myo-3p::GFP prey were washed with M9, filtered two times with a 20-µm nylon filter and centrifuged at 200 rpm to extract a pure larval culture. Then, 0.5 µl of the pellet was transferred onto a 6-cm NGM imaging plate. The larvae were allowed to disperse undisturbed for at least 1.5 h. P. pacificus Ppa-myo-2p::RFP young adults were starved for 2 h and subsequently transferred onto the imaging plates. Worms were recorded with a dual-colour epifluorescence tracking microscope29. The microscope featured a 16-mm objective and a 50-mm tube lens, resulting in a magnification of approximately ×3.1. The camera used was a Basler acA3088-57um. To compensate for the different brightness of the fluorophores, the red channel was attenuated by a neutral density filter with an optical density of 0.6. Recordings of individual predators were analysed using a similar approach to the large population recordings with an adaptation to account for the stage motion. Prey signals were extracted from the GFP channel with a 22-µm-wide circular mask, centred at the anterior end of the predator using the extracted centreline of the pharynx as a guide. Prey signals was calculated as:

$${\rm{Prey}}\,{\rm{signal}}=\frac{({{\rm{GFP}}}_{\text{95 percentile}}-{{\rm{GFP}}}_{\text{5 percentile}})}{{{\rm{GFP}}}_{\text{5 percentile}}}$$

Tracks were aligned to the onset of biting events, and the prey signal was normalized to the baseline, defined as 15 to 5 s before bite onset:

$${\rm{\text{Prey signal}}}\,{\rm{ \% }}=\frac{({\rm{P}}{\rm{r}}{\rm{e}}{\rm{y}}\,{\rm{s}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{g}}{\rm{n}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{l}}-{\rm{B}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{s}}{\rm{e}}{\rm{l}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{n}}{\rm{e}})}{{\rm{B}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{s}}{\rm{e}}{\rm{l}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{n}}{\rm{e}}}$$

Statistics were performed using an upper-tailed paired t-test, comparing the mean prey signal (%) of 15 to 5 s before bite onset and 0 to 15 s. To investigate the ingestion of GFP-labelled body wall muscle by the predator, we analysed the signal of the green channel subtracted (background subtracted with the ‘rolling ball’ algorithm in ImageJ with a 10-px (7.4 µm) radius). A kymograph was extracted along the centreline of the pharynx using ImageJ for one exemplary video. The video was selected because the predator was stationary for a prolonged time of 30 s, whereas the focal plane clearly showed ingestion of labelled food. The linewidth of the kymograph was 6 px (4.4 µm). To detect individual ingestion events, peak detection was performed using a segment of the kymograph in the range of the metacorpus where the ingested food was most easily visible. The intensity values in this region were averaged for each time point.

Statistical analysis

For the statistical analysis of the state predictions (relative time in state, mean bout duration, transition rates), and for the corpse assay, the two-tailed Mann–Whitney U-test was used. The statistical analysis was performed on each condition and state with its respective control. A Bonferroni correction was applied to take into account that the probability of a false-positive significant test rises with the number of compared conditions. Thus, the P values reported here are corrected for the number of comparisons made with the respective control. All raw P values and sample sizes are available in Supplementary Table 3. The box plots follow Tukey’s rule for which the middle line indicates the median, the box denotes the first and third quartiles, and the whiskers show the 1.5 interquartile range above and below the box. In all figures, * denotes a significance value between 0.05 and 0.01, ** a significance value between 0.01 and 0.001, *** a significance value between 0.001 and 0.0001, and **** a significance below 0.0001.

Generation of CRISPR–Cas9-induced mutations

The procedure for CRISPR–Cas9 mutagenesis was based on previously described P. pacificus methods63. Briefly, gene-specific CRISPR RNAs were designed to target early predicted exons in all target genes and synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT). These were then fused to tracrRNA (IDT) at 95 °C for 5 min before cooling to room temperature and annealing. The hybridization result was coupled with purified Cas9 protein (IDT). After 5 min of incubation at room temperature, Tris-EDTA buffer was added to achieve a final concentration of 18.1 μM for single guide RNA (sgRNA) and 12.5 μM for Cas9. The mix was injected in the gonads of young adults. P0 worms were discarded 12–24 h after microinjection. After 2 days, 96 F1 progeny from P0 plates were singled out and allowed to lay eggs for 24 h. The genotypes of the F1 animals were subsequently analysed through Sanger sequencing. For detailed information about the mutants created during this study, see Extended Data Fig. 9 and Supplementary Table 1. All sgRNAs and the primers used in this study to generate mutants can be found in Supplementary Table 2.

Pharmacological experiment

To quantify the effects of exogenous octopamine and tyramine, predatory feeding assays were performed on agar plates which were supplemented with 2 mM octopamine and tyramine, respectively. Tyramine and octopamine plates were prepared by adding tyramine-HCl (Sigma) and octopamine-HCl (Sigma) to a concentration of 2 mM to freshly autoclaved NGM that was cooled to 55 °C before use. Ppa-myo-2p::RFP animals were picked onto either unseeded octopamine- or tyramine-containing plates and starved for 2 h. These animals were subsequently added to standard assay plates with C. elegans larvae contained in a copper arena and also containing octopamine or tyramine12.

Egg-laying assay

Three-day-old adult worms were placed on individual plates seeded with OP50. The following day, the number of eggs was manually counted and the worms were transferred onto new plates. The eggs were counted for 5 days per individual worm after which only unfertilized eggs were laid.

Manual predation assays

Assays were conducted as previously reported16. Briefly, prey were maintained on NGM plates seeded with OP50 bacteria until freshly starved, resulting in an abundance of young larvae. These plates were washed with M9 and passed through two 20-μm filters to isolate larvae. Then, 1.0 μl of C. elegans larval pellet was transferred onto a 6-cm unseeded NGM plate. Five predatory nematodes were screened for the appropriate mouth morph and added to assay plates for prey assays. After 2 h the plate was screened and corpses were counted manually.

Worm size measurement

Synchronized J2 larvae were placed onto NGM plates with bacteria. They were transferred from assay plates to NGM plates without bacteria during different developmental points (24, 48 and 72 h). Bright-field images of the worms were taken using an epifluorescence microscope (Axio Zoom V16; Zeiss) and the Basler camera (acA3088-57um; BASLER). Images were analysed using the Wormsizer plugin for ImageJ/Fiji. Wormsizer detects and measures the area of the worms.

Mouth-form phenotyping

Mouth-form phenotyping was performed as previously reported17. In brief, NGM plates with synchronized young adults were placed onto a stereomicroscope with high magnification (×150). Then, 100 worms were screened for the mouth form per strain. The eurystomatous mouth form was determined by the presence of a wide mouth, whereas the stenostomatous forms were determined by a narrow mouth. Eurystomatous young adult worms were picked for predation assays. Images of mouth forms were taken using a differential interference contrast (DIC) ×60 lens with a ×1.6 magnifier.

Ppa-myo-2p::RFP copy number quantification

Thirty J4/young adult hermaphrodites from a non-starved plate were picked for DNA extraction using a NEB Monarch DNA kit (final elution volume 35 µl). A whole plate of non-starved worms was used for RNA extraction using a Zymo RNA mini kit (final elution volume 30 µl). To determine the copy number of Ppa-myo-2p::RFP in the ultraviolet integrated transgenic line (JWL27) and relative expression of this construct, quantitative PCR (qPCR) and qPCR with reverse transcription assays were conducted. For copy number, primers were designed to amplify a part of the RFP sequence and compared with two known single-copy gene sequences, Ppa-gpd-3 and Ppa-csg-1. As Ppa-myo-2p::RFP is a transcriptional reporter, no part of the Ppa-myo-2 gene sequence is included in the reporter line. Therefore, to determine the relative expression of Ppa-myo-2p::RFP, the expression of RFP was compared with that of the native Ppa-myo-2 exon gene sequence. qPCR primers specific for RFP were: forward GGAGAGGGAAAGCCTTACGAGG and reverse GAATCCCTCAGGGAAAGACTGC. Two pairs of gene-specific Ppa-myo-2 primers were used. These were pair 1: forward CGAAGAAGAACGTGTGGGTG and reverse TACCTCATTGCCGGGACCTC; and pair 2: forward AGGAGACAAAGGGAGACACG and reverse GGGTTCATCTCCTGCACTTGG. For quantification, DNA samples were 1:10 diluted with water, whereas RNA samples were not diluted. Three technical replicates and two biological replicates were conducted.

HCR

HCR RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization was performed in P. pacificus using a modified version of the protocol described previously64. The protocol was adjusted to include an extended Proteinase K treatment step (final concentration of 200 µg ml−1 for approximately 1 h at room temperature) to improve tissue permeability and probe penetration. Worms were incubated overnight at 37 °C in probe hybridization buffer containing 200 pmol of each probe set. We examined gene expression using dual and triple HCR labelling. The genes Ppa-tbh-1 labelled with X1-488 and Ppa-tdc-1 labelled with X2-647 were imaged together. Similarly, Ppa-klp-6 labelled with X1-488 and Ppa-ser-3 labelled with X2-647 were co-detected in the same specimens. Triple labelling was carried out to visualize Ppa-ser-3 using B2 (Alexa Fluor 546) probes, Ppa-ser-6 using Ppa-ser-6 to B3 (Alexa Fluor 488) probes and Ppa-lgc-55 using B1 (Alexa Fluor 647) probes.

Generation of HisCl transgenic strains

To silence neurons in P. pacificus, we used a codon-optimized version of the C. elegans histamine-gated chloride channel (HisCl1), following the strategy described previously65,66. For RIM and RIC neuronal silencing, the codon-optimized HisCl1 sequence was inserted downstream of the Ppa-tdc-1 promoter (1,585 bp) to generate the Ppa-tdc-1p::HisCl plasmid. For IL2 silencing, the Ppa-klp-6 promoter (2 kilobases) was used to generate the Ppa-klp-6p::HisCl plasmid. For microinjections, the Ppa-tdc-1p::HisCl injection mix contained 10 ng µl−1 of SalI-HF-digested Ppa-tdc-1p::HisCl plasmid, 10 ng µl−1 of PstI-HF-digested Ppa-mec-6p::Venus plasmid as a co-injection marker and 60 ng µl−1 of PstI-HF-digested genomic carrier DNA. For the Ppa-klp-6p::HisCl injection mix, this contained 10 ng µl−1 of PstI-HF-digested Ppa-klp-6p::HisCl plasmid, 10 ng µl−1 of PstI-HF-digested Ppa-klp-6p::GFP plasmid as a co-injection marker and 60 ng µl−1 of PstI-HF-digested genomic carrier DNA. Transgenic animals were identified by GFP or Venus expression and maintained as extrachromosomal lines for subsequent behavioural analysis.

Preparation of histamine-containing assay plates

To induce neuronal silencing through activation of HisCl1 channels, NGM was supplemented with 10 mM histamine dihydrochloride, as described previously65,66. The 1 M histamine stock solution was prepared in sterile distilled water and added to molten NGM cooled to approximately 60 °C at a volume of 5 ml per 500 ml of agar. Plates were poured, allowed to solidify at room temperature and used within 1 week. These histamine plates were used both during the 2-h starvation period before behavioural assays and during the assays themselves.

Behavioural assays for neuron silencing

Behavioural assays were conducted post silencing to examine the roles of RIC and RIM neurons for functional octopamine and tyramine release, as well as the importance of the IL2 neurons for predatory aggression. For IL2 neuron silencing, 40 young adult Ppa-klp-6p::HisCl animals (eurystomatous morph) were starved for 2 h on 10 mM histamine plates and subsequently transferred to an assay arena consisting of a 10 mM histamine plate containing C. elegans L1 larvae as prey. After a 15-min recovery period, predator behaviour was recorded for 10 min. To silence RIM and RIC neurons, Ppa-tdc-1p::HisCl animals in a tbh-1 mutant background were used. Animals were placed on 10 mM histamine plates seeded with OP50 bacteria overnight before the assay to ensure prolonged silencing and minimize any residual tyramine release from RIM or RIC neurons. Prey assay conditions were otherwise identical to those described for IL2 silencing.

Gene phylogenetic analysis

The predicted evolutionary history of the neuromodulator biosynthesis enzymes and associated receptors was determined by reciprocal best BLAST matches with gene predictions in genome assemblies for P. pacificus and C. elegans. Phylogenetic inference was conducted on the amino acid sequence using the Maximum Likelihood criterion and a Jones–Taylor–Thornton matrix-based model. The tree with the highest log likelihood is shown. Initial tree(s) for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying Neighbor-Join and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using the Jones–Taylor–Thornton model, and then selecting the topology with superior log likelihood value. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA X67.

Nematode species phylogeny

A species phylogeny was adapted from previous work68. The original tree was redrawn and simplified to show only the branching order (topology) and emphasize species relationships. Branch lengths were omitted, as relative divergence times are not relevant for the present analysis.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.