Strains

T7 Express Escherichia coli (New England Biolabs, C2566) were used for MFE and ODMR experiments in Figs. 1–3. E. coli MG1655 cells were used for multiplexing and mother machine lock-in experiments in Fig. 4, owing to its effectiveness as a heterologous gene expression strain, and past optimization of mother machine chip loading protocols for this host. MG1655 was also used for Fig. 5. NEB Dh5α E. coli was used for plasmid production and genetic engineering steps, but not experimental data collection.

Cell media

TB auto-induction medium (Formedium, AIMTB0260) was used for growth of liquid cultures of T7 Express strains. LB medium (Formedium, LBX0102) was used for growth of MG1655 strains in liquid cultures and agar plates (Formedium, AGR10). M9 medium (Formedium, MMS0102; supplemented with 0.2 g l−1 Pluronic F-127 (Sigma Aldrich, P2443-250G), 0.34 g l−1 thiamine hydrochloride, 0.4% glucose, 0.2% casamino acids, 2 mM MgSO4, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 50 mg l−1 EDTA Na2.2H20, 5 mg l−1 FeCl3, 0.84 mg l−1 ZnCl2, 0.13 mg l−1 CuCl2.2H2O, 0.05 mg l−1 CoCl2, 0.1 mg l−1 H3BO3 and 0.016 mg l−1 MnCl2.4H2O) was used for mother machine experiments. Antibiotic stocks were prepared as follows: 100 mg ml−1 carbenicillin (Formedium, CAR0025) dissolved in 50% (v/v) ethanol and 20 mg ml−1 chloramphenicol (Fisher, 10368030) dissolved in 100% (v/v) ethanol; stocks were diluted 1,000× for experiments.

Plasmid construction

Whole plasmid sequencing was performed by Plasmidsaurus using Oxford Nanopore Technology.

Derivative plasmids of those generated by directed evolution (for example, MagLOV + mCherry) were constructed using the EcoFlex kit (Addgene kit 1000000080) following standard EcoFlex protocols61. Level 1 assemblies were performed using NEB BsaI-HFv2, NEB T4 DNA Ligase Reaction Buffer (B0202S) and Thermo Scientific T4 DNA Ligase (EL0011). Level 2 assemblies were performed using NEBridge Golden Gate Assembly Kit BsmBI-v2 and NEB T4 DNA Ligase Reaction Buffer (B0202S).

Level 1 PCR cycling protocol: 30× (5 min at 37 °C → 5 min at 16 °C) → 10 min at 60 °C → 20 min at 80 °C.

Level 2 overnight PCR cycling protocol: 65× (5 min at 42 °C → 5 min at 16 °C) → 10 min at 60 °C → 20 min at 80 °C.

pTU1 was used as a negative control plasmid (Supplementary Note 2); it is part of the EcoFlex kit.

pRSET-AsLOV_R2, pRSET-MagLOV, pRSET-MagLOV-2 and pRSET-MagLOV-2_R11-f plasmids (used for Figs. 1–3) contain MFP variants created via directed evolution (described below) under control of T7 promoters. It is noted that despite the T7 promoter being chemically inducible in its host strain, experiments were performed without induction (that is, transcription was owing to leaky expression).

pVS-01-03_EGFP expressing EGFP was used for microfluidic experiments. It was assembled solely from EcoFlex parts (pTU1-B-RFP, pBP-J23108, pBP-pET-RBS, pBP-ORF-eGFP and pBP-BBa-B0012).

pVS-02-04_mCherry+MagLOV was used for microfluidic experiments. EcoFlex Golden Gate assembly was used to create a plasmid that expresses both MagLOV and mCherry. In a level 1 reaction, pVS-01-01_mCherry and pVS-01-02_MagLOV were assembled using the following bioparts from the EcoFlex kit. pVS-01-01_mCherry: pTU1-A-lacZ, pBP-J23108, pBP-pET-RBS, pBP-ORF-mCherry, pBP-BBa_B0012. pVS-01-02_MagLOV: pTU1-B-RFP, pBP-J23119, pBP-pET-RBS, BP-01_MagLOV, pBP-BBa_B0012. The BP-01_MagLOV sequence with overlaps was gained via PCR using NEB Q5 polymerase with pGA-01-01 as template using primers MagLOV_EcoFlex_FWD and MagLOV_EcoFlex_REV. Both plasmids were combined in a subsequent Level 2 EcoFlex reaction with the pTU2-a backbone, leading to pVS-02-04_mCherry+MagLOV. The predicted translation rate is 250.

pRH-01-17, pGA-01-47 and pGA-01-49 were used for multiplexing experiments and spatial localization. The coding sequences (CDSs) for AsLOV2 R5, MagLOV 2 and MagLOV 2 fast, respectively, were codon optimized and the ribosome binding site (RBS) designed to maximize constitutive expression using the CDS Calculator and RBS Calculator tools of ref. 62. The sequence was synthesized as a gene fragment (Twist Bioscience) and assembled into a level 1 plasmid as above, again using the J23119 promoter.

MFP expression levels were estimated for constructs using ref. 62. For pVS-02-04, an unoptimized codon sequence and RBS were used, resulting in a predicted translation rate in its expression strain (E. coli MG1655) of 261. For pRSET constructs, the predicted translation rate in expression strains (E. coli NEB T7) is 50 × 103. For pRH-01-17, pGA-01-47 and pGA-01-49, the optimized codon sequence and RBS yielded a predicted translation rate in E. coli MG1655 of 106; as such this represents a 20× increase in predicted rate over the pRSET strains and a 4,000× increase in predicted translation over pVS-02-04. It is noted that these predictions also do not account for the dual expression in pVS-02-04 of mCherry.

Directed evolution of MFPs

We previously reported the directed evolution of MFPs resulting in MagLOV8. Directed evolution of MFP variants was initiated with AsLOV2 C450A39, a protein originally isolated from the common oat Avena sativa. The mutagenesis protocol was based on methods developed previously63. In particular, we used 142 PCR reactions with NNK semi-random primer pairs (supplied by Eton Bioscience) to make all single amino acid mutants of AsLOV2 (404–546) C450A at all locations, which produces a library containing 2,982 protein variants, although (owing to the pooled nature of the screen) it is likely that not all variants are present for each round. This library was transformed into E. coli strain BL21(DE3) and spread across about ten LB-agar plates for screening. After transformation, plates were left for 2 days at room temperature (25 °C) as this was observed to lead to stronger magnetoresponses. Screening used the same fluorescence photography system described in ref. 63, with addition of an electromagnet (KK-P80/10, Kaka Electric) below the sample, which was turned on/off every 15 seconds using an Arduino Uno while acquiring successive images. After each screen, images were processed to identify the single colony (across all plates) with the largest fractional change in fluorescence between the magnet on/off conditions. The selected colony was picked (manually) from the corresponding plate, and used as the basis for the next round of mutagenesis and selection. Subsequent mutagenesis rounds used the same primers to avoid re-making the primer library with each mutation (which we hypothesize selects against multiple consecutive nearby mutations), except before rounds leading to AsLOV R5, MagLOV R7 and MagLOV 2, at which point primers in the library that overlapped mutated sites were updated to the current variant’s sequence. In total, 11 rounds of mutagenesis were undertaken, all selecting for amplitude of MFE with the exception of round 11 (MagLOV 2 fast) where mutants from round 10 were selected based on fast response time (quantified as the mutant with the largest contrast measured in the first 100 ms following magnetic-field change). After each round of mutagenesis, selected variants were sequenced using the Sanger method (supplied by Quintara Biosciences). The variants measured in this paper and some intermediaries are provided in Supplementary Note 3.

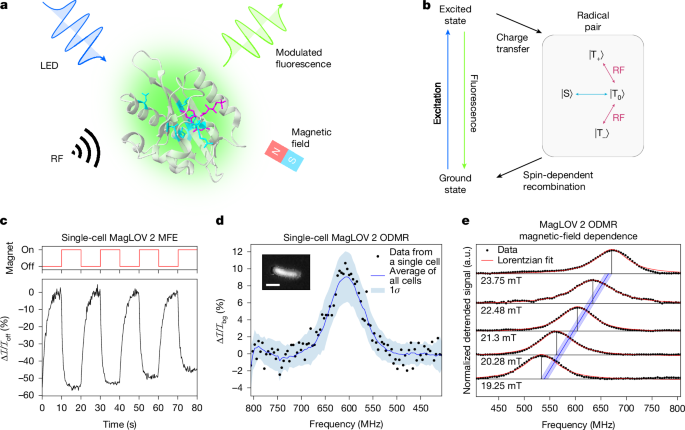

Wide-field MFE and ODMR characterization

Plasmids expressing EGFP, MFP variants or negative control plasmids expressing only antibiotic selection markers were used to transform E. coli NEB T7 via heatshock at 42 °C for 45 seconds. Colonies were grown overnight at 37 °C on Agar plates, then a single colony was picked, resuspended in 1 ml LB media, spread onto a plate, and grown at 37 °C for 24 hours followed by 24 hours at room temperature to form a lawn of cells. Cells from this lawn were then resuspended in PBS buffer.

Both MFE and ODMR imaging were performed using a custom-built wide-field epifluorescence microscope (Supplementary Notes 10 and 11). From cells suspended in PBS buffer, an approximately 1-μl droplet was confined between two glass coverslips (SLS MIC2162) atop a stripline antenna printed circuit board (Supplementary Note 12). The antenna printed circuit board was placed inverted on the microscope stage and either an electromagnet (for MFE) or a permanent magnet (for ODMR) was positioned above. The antenna printed circuit board was used to mount the MFE experiments (despite not delivering any B1 field) to that ensure lighting conditions were consistent with those in ODMR experiments. For MFE experiments, the electromagnet supplied a static field of 0 mT or 10 mT at the sample. For ODMR experiments, the permanent magnet supplied a static field (B0 ≈ 20 mT) in the z direction (Supplementary Note 13), perpendicular to the radio-frequency field (B1 ≈ 0.2 mT) supplied by the stripline antenna (Supplementary Note 14). It is noted that the imaging step and exposure times (Supplementary Note 11) were maintained across experiments unless otherwise stated, whereas light-emitting-diode power levels (Supplementary Notes 9 and 15) were varied between samples to account for differing expression levels of MFPs.

Data processing was performed using Python (v3.11.11), SciPy (v1.15.1)64, NumPy (v.126.4)65, scikit-learn (v1.6.1)66 and scikit-image (v0.20.0)66.

Calculation of MFE and ODMR effect sizes

We define the MFE by \(\Delta {\mathcal{I}}/{{\mathcal{I}}}_{\mathrm{off}}\), where \({\mathcal{I}}\) is the fluorescence intensity, \({{\mathcal{I}}}_{\mathrm{off}}\) is the fluorescence intensity immediately before switching the magnet on, and \(\Delta {\mathcal{I}}={\mathcal{I}}-{{\mathcal{I}}}_{\mathrm{off}}\). Similarly, for ODMR measurements, the detrended signal is defined to be \(\Delta {\mathcal{I}}/{{\mathcal{I}}}_{\mathrm{bg}}\), where \({{\mathcal{I}}}_{\mathrm{bg}}\) is a background curve fit to the data as described in Supplementary Note 9, and \(\Delta {\mathcal{I}}={\mathcal{I}}-{{\mathcal{I}}}_{\mathrm{bg}}\).

Spectral measurements

Wavelength-resolved MFE measurements (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Note 4) were performed in bulk using a home-built cuvette-based fluorescence spectrometer described in ref. 24. In brief, a 450-nm laser diode was used to excite the sample, which was housed inside custom-built Helmholtz coils. The emission was collected through a lens pair and dispersed by a spectrograph (Andor Holospec) onto a charge-coupled-device array (Andor iDus420).

Cells were resuspended in PBS buffer at an optical density of about 0.3 and placed in a quartz fluorescence cuvette (Hellma). Similarly to the wide-field measurements, a magnetic field was switched on and off with field strength 10 mT and a period of 20 seconds (10 seconds on, 10 seconds off). The sample was illuminated at 450 nm (Oxxius LBX-450), at roughly 1 kW m−2, and the emission was filtered using a 458-nm longpass filter (RazorEdge ultrasteep).

Excitation spectra in Fig. 3c and Supplementary Note 4 were recorded using an Edinburgh Instruments FS5 Spectrofluorometer, using a xenon lamp as an excitation source. Emission spectra (Fig. 3a) and time-resolved emission spectra (Supplementary Note 4) were recorded on the same instrument, but using an HPL450 (450 nm) for excitation. It is noted that this instrument set-up suffers from laser excitation artefacts, which create the small peaks near 550 nm and 650 nm.

Multiplexing using MFE

To demonstrate the potential of using MFE for multiplexing in fluorescence microscopy, we first cloned strains of AsLOV R5 (one of the variants evolved between AsLOV R2 and MagLOV; Supplementary Note 3) and MagLOV 2 into E. coli MG1655. Cells were grown in liquid culture from −80 °C freezer stocks, then resuspended in PBS and made up to equal concentration as measured by optical density (OD600). Individually, and as a 1:1 mixture, monolayers of cells were sandwiched between a glass slide and cover for MFE imaging.

We initially characterized each variant in isolation, measuring fluorescence traces for approximately 2,000 cells in a field of view (Fig. 4a). The same processing was performed as in Fig. 2 but to individual cells, yielding a value of τ (the MFE saturation timescale) for each cell, which allows measurement of each sample’s intrapopulation variability (Fig. 4b).

To perform the population decomposition, we trained a machine-learning classifier (XGBoost67) on the dynamic data (that is, fluorescence versus time) used to generate Fig. 4b. Before training, and for classification, the MFE response (\(\Delta {\mathcal{I}}/{{\mathcal{I}}}_{\mathrm{off}}\)) curves of each cell were normalized to range from 0 to 1. Without further training, this classifier was used to classify a combined population of cells (Fig. 4b) mixed with 1:1 ratio (determined by OD600). The ratio of the two variants by classification was R5:ML2 = 0.9:1, which probably differs from the anticipated 1:1 ratio owing to both classifier accuracy and typical measurement errors expected from the use of OD600 to quantify cell counts68.

Lock-in detection using MFE

Cells expressing EGFP49 and cells co-expressing mCherry69 with very weak MagLOV expression (expression level predicted62 at about 0.025% of that in multiplexing experiments) were grown in liquid culture, then mixed and loaded into a microfluidic ‘mother machine’ chip consisting of two rows of evenly spaced trenches fed by a central channel bringing fresh media into the system and carrying excess cells out. After a few hours of growth, each trench was filled only with cells whose ancestor is the cell at the closed end of the trench (that is, they may be considered clonal; Fig. 4d). The cells were imaged using the same wide-field fluorescence microscopy set-up as described previously. Microfluidic manufacturing and set-up techniques are described in Supplementary Note 7. Algorithms for cell segmentation and image processing and quantification are described in Supplementary Note 16. Quantitative lock-in classification results are provided Supplementary Note 17. In Fig. 4g, the classifications are shown including the decision boundaries based on the control (565-nm fluorescence) and based on the lock-in value. The graphs can be interpreted as confusion matrices: top-left quadrant are false negatives, top-right quadrant are true positives, bottom-left quadrant are true negatives, and bottom-right quadrant are false positives.

Spatial localization using ODMR

The fluorescence MRI instrument (described in detail in Supplementary Note 8) used a permanent neodymium rare-earth magnet to impose a static magnetic field, B0, which varied linearly along the z axis with a gradient strength of approximately 0.95 T m−1 at the radio-frequency isocentre of the coil used. Our methodology assumes that (1) this gradient is uniform within the coil and (2) there is no variation in x−y planes; violation of these assumptions would degrade the localization accuracy. The imaging isocentre is both spatially the centre of the radio-frequency coil’s sensitive area and was chosen to be at 17.8 mT corresponding to an ESR Larmor frequency of f ≈ 500 MHz, the coil’s resonant frequency. The magnetic field was modulated axially by a Helmholtz coil such that \({B}_{z}={B}_{z}^{{\rm{magnet}}}(z)+{B}_{z}^{{\rm{Helmholtz}}}(t)\) where t is time. By varying the Helmholtz coil current between ±1 A, we were able to shift the effective magnetic field by ±5.87 mT around the resonant condition, providing a total field of view of approximately 12 mT along the gradient direction (see Supplementary Note 8 for a detailed calculation). The device is therefore able to scan spatially in one dimension as the Larmor frequency remains fixed at \(f={\bar{\gamma }}_{e}{B}_{z}(z,t)\), where different spatial positions are brought into resonance through current modulation while maintaining fixed radio-frequency excitation.

To simulate a three-dimensional volumetric sample, we cast a 40-cm3 volume of PDMS (matching the region of uniformity of the radio-frequency coil) with empty cylinders of 0.4-mm-diameter embedded in it perpendicular to the B0 gradient and separated in z by 7.5 mm. We filled these cylinders with cells expressing MagLOV 2 fast (centrifuge-concentrated liquid culture), measuring at different depths both individually and together. Intensity data were processed (grey solid area in Fig. 5e,f) using a Lucy–Richardson deconvolution64 with a Gaussian impulse response function of fixed width 3 mm, which is estimated based on the ODMR linewidth of 80 MHz (see Supplementary Note 8 for further details). It is noted that although the deconvolution algorithm uses the known ODMR linewidth (and hence point-spread function), it does not make any assumption about the number or location of peaks.

This fluorescence MRI instrument was designed and built to achieve proof of concept and is limited in terms of signal-to-noise performance of the optical path and photodiode sensor, as well as B0 field uniformity in the target volume. Future development could significantly improve its capabilities via implementing full three-dimensional control of B0 field gradients, an endoscope-type imaging system to collect light with x–y spatial information from the target volume without sensor perturbation by radio frequency or magnetic field, addition of fast optical lock-in to the fluorescence excitation or measurement, optical path re-design to improve collection and filtering efficiency and reduce stray light, and indeed directed evolution of variants with faster ODMR response dynamics to allow averaging over more on/off cycles.

Microenvironment sensing

Purified MagLOV 2 fast solutions for the data in Fig. 6 were prepared as follows. It is noted that all MagLOV proteins expressed include a His-tag at the N-terminus. Protein was purified following using HisPur Cobalt Resin (Thermo Scientific) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Purified protein was suspended in PBS buffer with 30% glycerol and stored at −80 °C.

We estimated the concentration the purified protein samples via the method used in ref. 70 to determine the extinction coefficient of LOV-based fluorescent proteins. First, purified protein was heated to 95 °C for 5 minutes to dissociate the FMN from the protein (we assume that one FMN corresponds to one protein, as free FMN should be removed by the protein purification process). The concentration of flavin (and hence protein) was then determined by performing a serial dilution and measuring absorbance at 450 nanometres (A450nm), using the free FMN extinction coefficient ϵFMN = 12,200 M−1 cm−1 (ref. 71).

Contrast agent experiments were performed on the wide-field microscope configured for MFE detection, using a six-chamber microfluidic chip (ibdi μ-Slide VI 0.5 Glass Bottom) to hold samples of gadobutrol (CRS Y0001803) diluted in PBS buffer in serial dilution (MagLOV concentration the same for all conditions). Measurements were acquired in a randomized sequence (to compensate for any stray light photobleaching or time and sequence correlated effects) by programming 6 × 3 fields of view (6 chambers of differing concentrations, 3 fields of view in each chamber), then automatically performing an MFE measurement acquisition at each field of view. For each MFE acquisition, 10 periods of duration 40 seconds (20 seconds magnet on, 20 seconds off) were acquired at 450-nm light-emitting-diode intensity 280 mW cm−2, 100-ms image exposure time and 10-mT magnetic-field strength. Optimization of experimental protocols for spin-relaxometry-based sensing using MagLOV or other radical-pair fluorescent proteins will be required for broader application; here we demonstrate simply that the spin-radical pair of MagLOV is indeed sensitive to its surroundings despite the flavin being bound.

To consider the expected effect of paramagnetic species upon the MagLOV MFE more quantitatively, we note that paramagnetic impurities can be modelled as stochastic point dipoles that modify the T1 or T2 relaxation rates in radical-pair kinetics72, thereby changing the contrast. We therefore anticipated that a characteristic timescale for this process, τ, would scale as \(\tau \approx \frac{1}{{k}_{{\rm{STD}}}}+{\left(\frac{1}{T}+R[{{\rm{Gd}}}^{3+}]\right)}^{-1}\) where kSTD is a stochastic decoherence rate, T is a semiempirical T1 or T2 relaxation time, and R the effective relaxivity of the paramagnetic impurity. We therefore expect contrast to fit a functional form of approximately (a[x] + b)−1 + c, and indeed this is consistent with Fig. 6.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.