Quantum mechanics predicts that single particles that have mass can behave as waves that do not have a definite location in space. Instead, such matter waves spread across a superposition of multiple locations at any given time, similar to how ripples generated by throwing a rock into a lake extend across the surface of the water. A striking consequence of this ‘wave–particle duality’ is that massive particles can form interference patterns, similar to those seen when water or light waves overlap. This matter-wave interference has often been observed for microscopic particles, such as electrons, neutrons and atoms, but whether it can occur for macroscopic objects remains an active topic of debate1.

Read the paper: Probing quantum mechanics with nanoparticle matter-wave interferometry

Writing in Nature, Pedalino et al.2 report the experimental demonstration of matter-wave interference with the heaviest objects so far: sodium nanoparticles with masses exceeding 170,000 daltons (Da). These results raise fundamental questions about the range of masses for which wave–particle duality occurs.

The idea that macroscopic objects could exhibit wave–particle duality contrasts with people’s intuition from everyday life: we are accustomed to large objects having well-defined positions. However, standard quantum theory does not impose a size limit on the objects it describes. There is therefore no fundamental rule preventing a cat from being in a superposition of one place and of another — or from being simultaneously alive and dead, as considered in Erwin Schrödinger’s famous thought experiment3.

Schrödinger intended his thought experiment to show that it would be nonsensical to apply quantum superposition to macroscopic objects. To avoid such counter-intuitive behaviour, some physicists have proposed modifications to the laws of quantum mechanics. These ‘collapse models’ minimally affect the behaviour of the smallest objects, but rapidly destroy spatial superpositions of more massive objects, thereby setting a firm dividing line between what happens in the microscopic and macroscopic worlds1.

A step closer to atom lasers that stay on

Other physicists suggest that quantum mechanics does not need to be changed, because uncontrolled interactions of an object with its environment prevent matter-wave interference from appearing4. In this line of thinking, wave–particle duality could, in principle, apply to arbitrarily massive objects, but environmental interactions would make it impractical to observe as object mass increases.

Experiments to distinguish between the validity of collapse models and standard quantum mechanics are limited by how much the interactions of objects with their environment can be reduced. However, innovations are constantly increasing the mass at which matter-wave interference can be observed. For example, a 2019 experiment5 reported wave–particle duality of large molecules containing up to 2,000 atoms, with masses exceeding 25,000 Da. Pedalino et al. have now established matter-wave interference for a new, and even more massive, type of object: metal nanoparticles.

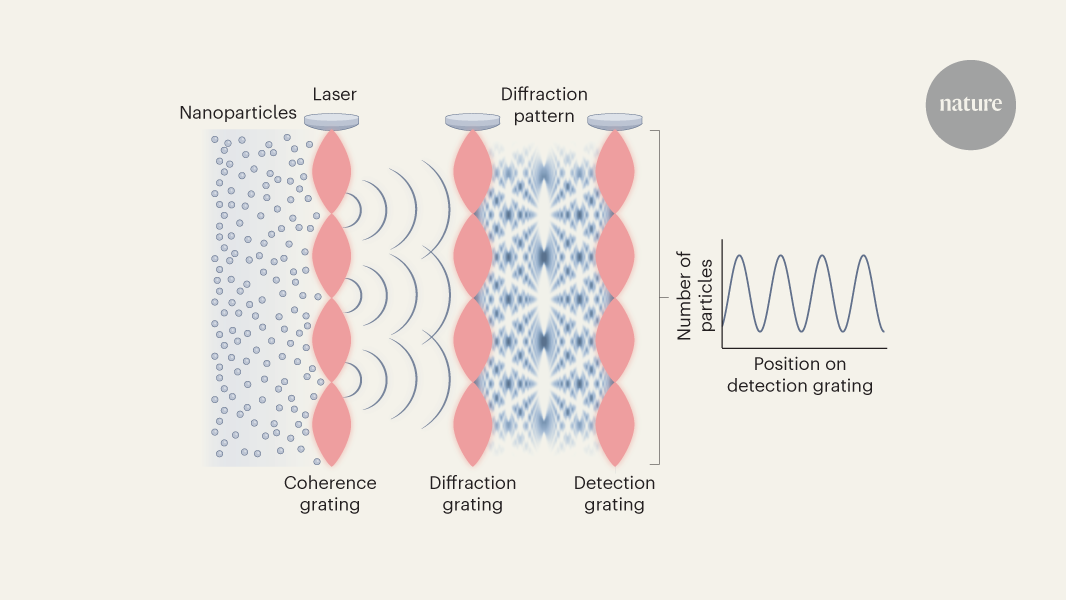

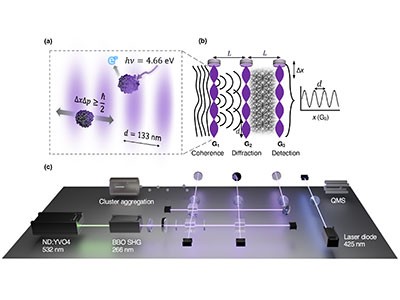

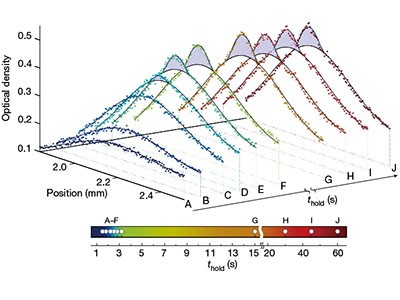

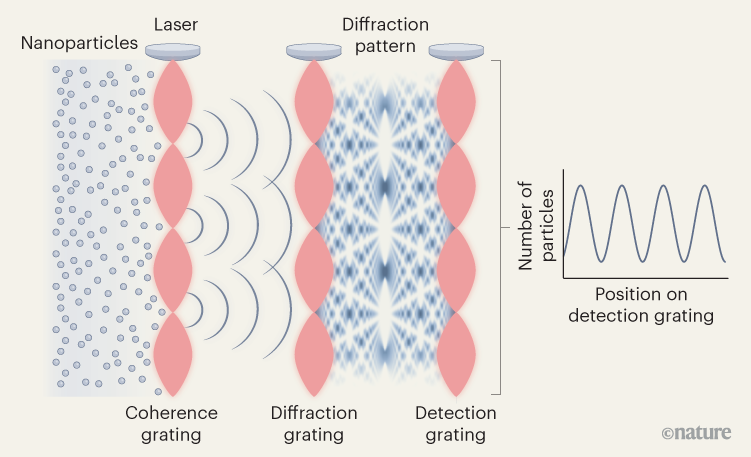

The authors passed ultracold sodium nanoparticles through a series of standing waves formed by laser beams. The standing waves act as gratings that generate and detect interference of the nanoparticles’ matter waves (Fig. 1) — similar to the way in which light that passes through a physical grating generates a diffraction pattern. To protect the nanoparticles from environmental disturbances, the authors implemented an extensive system to prevent vibrations in the environment from affecting the experiment. They also fine-tuned the orientation of the apparatus to suppress the influences of gravity and Earth’s rotation.

Figure 1 | Matter-wave interference has been detected for nanoparticles. Quantum mechanics predicts that even particles that have mass can behave as waves, known as matter waves. Pedalino et al.2 have observed interference of the matter waves of sodium nanoparticles — the largest objects for which such interference has been observed so far. The authors directed nanoparticles through a series of laser-produced standing waves, which act as gratings. The first grating produced matter waves that all oscillated in step with each other (such waves are said to be coherent) because they passed through only at the nodes of the standing wave. The second grating produced an interference pattern, and the third grating enabled particles to be detected and counted. By counting the number of particles that appeared at different positions along the third grating, the authors were able to resolve the fringes of the interference pattern.

The sodium nanoparticles used in the experiments consisted of more than 7,000 atoms and had masses of 170,000 Da. The study therefore confirms that standard quantum mechanics remains valid up to an impressively large scale, for objects that are much more complex and closer to being macroscopic than are individual atoms.

As Pedalino et al. note, experiments involving mechanical oscillators have also been used to probe quantum mechanics at scales much larger than those typically associated with quantum effects — for example, a superposition6 has been reported that involves objects with a mass of 1019 Da. That superposition, however, was spread over a distance of only 2 × 10–18 metres, which is much smaller than the size of a proton or neutron. By contrast, Pedalino and colleagues’ superpositions extended over 133 nanometres, much larger than the 8-nm diameter of the nanoparticles.

Do our observations make reality happen?

How does one decide which of these superpositions, occurring at such different mass and length scales, is more representative of macroscopic systems? One approach is to use a ‘macroscopicity’ metric7. This quantifies how strongly an experiment can rule out a class of collapse models that makes minimal changes to ordinary quantum mechanics. According to this metric, Pedalino and colleagues’ experiment is the most macroscopic quantum system reported so far, exceeding the previous record5 by more than tenfold.

Because the authors’ method is applicable to objects larger than nanoparticles, it holds promise for generating superpositions that are even more macroscopic than those currently reported. One challenge will be to distinguish genuine matter-wave interference from the ‘shadow patterns’ formed by the gratings — as the object mass increases, the matter waves will need more time to evolve freely between the gratings. To increase the evolution time, the velocity of the objects could be reduced or the distance between the gratings lengthened. This could enable the study of wave–particle duality in the 106 Da mass range. The evolution time could be extended further by switching the apparatus from a horizontal to a vertical orientation8–10, so that the objects fall large distances under gravity inside the apparatus. This strategy has the potential to facilitate matter-wave interference of objects with masses of up to 108 Da10.

Other schemes might enable experiments with even larger masses. For example, one proposal11 that uses magnetic fields to levitate and manipulate objects to generate matter-wave interference could be applicable to object masses exceeding 1013 Da. If sufficient isolation from environmental disturbances can be achieved, these experiments will shed light on the long-standing debate about whether gravity has a fundamental role in limiting the maximum size of quantum superpositions1,11. Various opinions exist on either side of this debate, and its resolution ultimately requires experimental tests.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.