Tissue processing and cell culture

Tissue samples

De-identified human tissue samples were collected with previous patient consent in strict observance of the legal and institutional ethical regulations. Protocols were approved by the Human Gamete, Embryo and Stem Cell Research Committee (Institutional Review Board) at the University of California, San Francisco.

The Primate Center at the University of California, Davis, provided four specimens of cortical tissue from PCD60 (n = 1), PCD75 (n = 1) and PCD80 (n = 2) rhesus macaques. All animal procedures conformed to the requirements of the Animal Welfare Act, and protocols were approved before implementation by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of California, Davis.

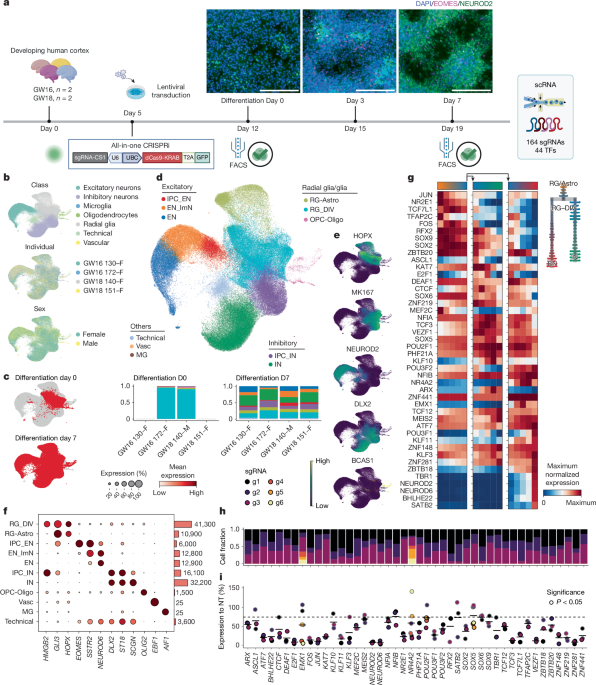

Cell culture and lentiviral transduction

For cryopreservation, tissue samples were cut into small pieces, placed in Bambanker (NIPPON Genetics, BB02), frozen in CoolCell at −80 and transferred to liquid nitrogen within 2 weeks. For single-cell dissociation, each cryovial was thawed in 37 °C warm water and placed in a vial containing a pre-warmed solution of Papain (Worthington Biochemical Corporation, catalogue no. LK003153) solution supplemented with 5% trehalose (Fisher Scientific, catalogue no. BP268710) that was prepared according to the manufacturer protocol for 10 min at 37 °C. After approximately 30 min incubation, tissue was triturated following the manufacturer protocol. Cells were plated on a 24-well tissue culture dish coated with 0.1% PEI (Sigma, catalogue no. P3143), 5 μg ml−1 Biolamina LN521 (Invitrogen, catalogue no. 23017-015) and at a density of 500,000 cells cm−2. Expansion medium contained insulin (Thermo Fisher, catalogue no. A1138IJ), transferrin (Invitria, catalogue no. 777TRF029-10G), selenium (Sigma, catalogue no. S5261-10G), 1.23 mM ascorbic acid (Fujifilm/Wako, catalogue no. 321-44823), 1% polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) (Sigma, catalogue no. P8136-1KG), 100 μg ml−1 primocin (Invivogen, catalogue no. ant-pm-05), 20 ng ml−1 fibroblast growth factor 2 (Preprotech, catalogue no. 100-18B) and 20 ng ml−1 EGF (Preprotech, catalogue no. AF100-15) in DMEM-F12 (Corning, catalogue no. MT10092CM), supplemented with ROCK inhibitor CEPT cocktail105. For lentiviral transduction, CRISPRi and STICR lentivirus was added to culture media on day 5 at roughly 1:500 and 1:5,000 dilution, respectively. After 6 h, the virus-containing medium was removed and replaced with fresh medium. Seven days after infection, expansion medium was removed and replaced with differentiation medium containing insulin-transferrin-selenium, 1.23 mM ascorbic acid, 1% PVA, 100 μg ml−1 primocin, 20 ng ml−1 BDNF (Alomone Labs, catalogue no. B-250) in DMEM-F12. At 7 days after differentiation, cultures were dissociated using papain supplemented with 5% trehalose and GFP-positive or GFP and mCherry co-positive cells were isolated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) on BD Aria Fusion, resuspended in 0.2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS and captured with 10x Chromium v.3.1 HT kit (catalogue no. PN-1000348) or Illumina Single Cell CRISPR Library kit (Illumina Single Cell CRISPR Prep, T10, catalogue no. 20132435).

Organotypic slice culture and lentiviral transduction

For organotypic slice culture experiments, samples were embedded in 3% low-melting-point agarose (Fisher, catalogue no. BP165-25) and then cut into 300-μm sections perpendicular to the ventricle on a Leica VT1200S vibrating blade microtome in oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid containing 125 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2 and 1.25 mM NaH2PO4. Slices were cultured slice medium containing in insulin-transferrin-selenium, 1.23 mM ascorbic acid, 1% PVA, 100 μg ml−1 primocin, Glutamax (Invitrogen, catalogue no. 35050061), 1 mg ml−1 BSA, 15 μM uridine (Sigma, catalogue no. U3003-5G), 1 μg ml−1 reduced glutathione (Sigma), 1 μg ml−1 (+)-α-tocopherol acetate (Sigma, catalogue no. t3001-10g), 0.12 μg ml−1 linoleic (Sigma, catalogue no. L1012) and linolenic acid (Sigma, catalogue no. L2376), 10 mg ml−1 docosahexaenoic acid (Cayman, catalogue no. 10006865), 5 mg ml−1 arachidonic acid (Cayman, catalogue no. 90010.1), 20 ng ml−1 BDNF in DMEM-F12. CEPT cocktail was added on the first day. Lentiviral transduction was performed on the following day locally at the germinal zone to preferentially label neural progenitor cells. CRISPRi and STICR lentivirus was added at 1:20 and 1:100 dilution, respectively. At 24 h after transduction, virus-containing medium was replaced with fresh medium and daily half-medium replacement was performed. At 12–14 days after transduction, cultures were dissociated using papain supplemented with 5% trehalose, and GFP- and mCherry co-positive cells were isolated by FACS and captured with 10x Chromium v.3.1 HT kit (catalogue no. PN-1000348).

Immunocytochemistry

Cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature and then in ice cold 90% methanol for 10 min. After a 1-h incubation in blocking solution (5% BSA, 0.3% Triton-X in PBS), cells were incubated with primary antibodies with the following dilution in blocking solution at room temperature for 1 h: mouse-EOMES (Thermo Fisher, catalogue no. 14-4877-82) 1:500, rabbit-NEUROD2 (Abcam, catalogue no. ab104430) 1:500, goat-SOX9 (R&D, catalogue no. AF3075) 1:300, mouse-KI67 (BD, catalogue no. 550609) 1:500, mouse-DLX2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalogue no. sc-393879) 1:200. The cells were then washed with PBS three times and incubated with secondary antibodies in blocking solution for 1 h at room temperature, and counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Finally, after PBS washes, digital image acquisition was performed using an Evos M7000 microscope and Evos M7000 Software.

Flow cytometry

Intracellular staining was performed using Foxp3 transcription factor staining kit (Invitrogen, catalogue no. 00-5523-00) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, cell culture was dissociated with Accutase (STEMCELL Technologies, catalogue no. 07920) supplemented with 5% trehalose (Fisher Scientific, catalogue no. BP268710) and fixed in Foxp3 fixation buffer for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were then washed twice with Foxp3 permeabilization buffer and then stained with primary antibodies mouse-DLX2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalogue no. sc-393879) and rabbit-NEUROD2 (Abcam, catalogue no. ab104430) at 1:100 dilution. After washing with Foxp3 permeabilization buffer, cells were stained with secondary antibodies donkey anti-mouse-488 and donkey anti-rabbit-647 (Invitrogen) at 1:200. Finally, cells were stained with conjugated antibodies KI67-421 (BD, catalogue no. 565929), SOX2-PerCP-Cy5.5 (BD, catalogue no. 561506), EOMES-PE-Cy7 (Invitrogen, catalogue no. 25-4877-42) at 1:100, washed twice with Foxp3 permeabilization buffer and resuspended in 0.2% BSA in PBS. Cells were then analysed directly by flow cytometry. Data were acquired through BD FACSDiva software and analysed with FlowJo. Fractions of marker positive populations were normalized to the mean value of two NT sgRNAs per individual sample at each timepoint. Two-sided Wilcoxon tests were performed on replicate mean against NT after collapsing two NT sgRNAs to identify significant changes in cell-type composition.

Immunohistochemistry

Primary cortical tissue were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS overnight, washed three times with PBS, then placed in 10% and 30% sucrose in PBS overnight, sequentially, and embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound for sectioning to 20 μm.

All samples were blocked in blocking solution (5% BSA, 0.3% Triton-X in PBS) for 1 h. Primary and secondary antibodies were diluted in blocking solution. Samples were incubated in primary antibody solution overnight at 4 °C, then washed three times with PBS at room temperature. Samples were then incubated in a secondary antibody solution with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole for 1 h at room temperature and then washed three times with PBS before being mounted with Fluoromount (Invitrogen, catalogue no. 0100-20). Primary antibodies used include mouse-DLX2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalogue no. sc-393879) 1:50; rabbit-SCGN (Millipore-Sigma, catalogue no. HPA006641) 1:500; rabbit-KI67 (Vector, catalogue no. VP-K451) 1:500; mouse-HOPX (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalogue no. sc-398703) 1:50; sheep-ARX (R&D, catalogue no. AF7068SP) 1:500. Secondary antibodies in this study include: donkey anti-sheep 647 (Thermo Fisher, catalogue no. A21448) 1:1,000, donkey anti-mouse 488 (Thermo Fisher, catalogue no. A32766) 1:1,000, donkey anti-rabbit 555 (Thermo Fisher, catalogue no. A32794) 1:1,000. Images were collected using ×20 air objectives on an Evos M7000 microscope, and processed using ImageJ/Fiji.

Target TF selection through enhancer-driven gene regulatory network inference

Two public datasets of single-cell multi omic developing human cortex10,12 were used for enhancer-driven gene regulatory network (eGRN) inference. The dataset from ref. 12 was subset randomly to 50,000 cells. Cells were grouped into meta cells using SEACells106 to overcome data sparsity and noise. On average, one meta cell contains 75 single cells and meta cells representing all the cell types originally presented in the dataset were input to the SCENIC+ workflow. Peak calling was performed using MACS2 in each cell type and a consensus peak set was generated using the TGCA iterative peak filtering approach following the pycisTopic workflow. The resulting consensus peaks were then summarized into a peak-by-nuclei matrix and used as input for topic modelling using default parameters in pycisTopic. The optimal number of topics (15) was determined based on four different quality metrics provided by SCENIC+. We applied three different methods in parallel to identify candidate enhancer regions by selecting regions of interest through (1) binarizing the topics using the Otsu method; (2) taking the top 3,000 regions per topic; (3) calling differentially accessible peaks on the imputed matrix using a Wilcoxon rank sum test (log2FC > 1.5 and Benjamini–Hochberg-adjusted P < 0.05). Pycistarget and discrete-element-method-based motif enrichment analysis were used to link candidate enhancers to TFs. Next, eGRNs, defined as TF-region-gene network consisting of (1) a specific TF, (2) all regions that are enriched for the TF-annotated motif and (3) all genes linked to these regions, were determined by a wrapper function provided by SCENIC+ using the default parameters and subsequently filtered according to the following criteria: (1) only eGRNs with more than ten target genes and positive region-to-gene relationships were retained; (2) eGRNs with an extended annotation was kept only if no direct annotation is available and (3) only genes with top TF-to-gene importance scores (rho > 0.05) were selected as the target genes for each eGRN. Specificity scores were calculated using the RSS algorithm based on region-or gene-based eGRN enrichment scores (area under the curve scores). To infer potential effects of TF repression on RG differentiation, in silico KD simulation was applied following the SCENIC+ workflow to a subset of TFs that showed high correlation between TF expression and target region enrichment scores. Briefly, a simulated gene expression matrix was generated by predicting the expression of each gene using the expression of the predictor TFs, while setting the expression of the TF of interest to zero. The simulation was repeated over five iterations to predict indirect effects. Cells were then projected onto an eGRN target gene-based PCA embedding and the shift of the cells in the original embedding was estimated based on eGRN gene-based area under the curve values calculated using the simulated gene expression matrix. Metrics including (1) normalized TF expression in RG, (2) scaled TF motif accessibility and target gene expression in RG, (3) predicted eGRN sizes, (4) cell-type specificity (RSS) of eGRNs and (5) predicted transcriptomic consequences in the RG lineage were used to select TF targets for this study (Supplementary Table 1).

Plasmids and lentivirus production

Plasmids

The all-in-one CRISPRi plasmid encoding dCas9-KRAB and sgRNA were obtained from Addgene (catalogue no. 71237). Capture sequence 1 was cloned into the vector by Vectorbuilder to enable sgRNA capture with 10x Genomics single-cell capture50. mCherry-H2B was cloned into the vector to substitute GFP for lineage tracing and flow cytometry experiments. For single sgRNA cloning, the oligonucleotides containing 20 bp protospacer and overhang were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies and cloned into the BsmBI-v2 (New England Biolabs, catalogue no. R0739)-digested backbone through T4 ligation (T4 DNA ligase, New England Biolabs, catalogue no. M0202). Protospacers were obtained from dual sgRNA CRISPRi libraries107 or Dolcetto52. For experiments in rhesus macaques, protospacers that were mapped uniquely to the rheMac10 genome were selected. STICR plasmids (Addgene catalogue numbers 180483, 186334, 186335) used for lineage tracing were obtained from the Nowakowski laboratory.

sgRNA library construction

Oligonucleotide pools were synthesized by Twist Bioscience. BsmBI recognition sites were appended to each sgRNA sequence along with the appropriate overhang sequences for cloning into the sgRNA expression plasmids, as well as primer sites to allow differential amplification of subsets from the same synthesis pool. The final oligonucleotide sequence was: 5′-(forward primer)CGTCTCACACCG(sgRNA, 20 nt)GTTTCGAGACG(reverse primer).

Primers were used to amplify individual subpools using 50 μl 2× NEBNext Ultra II Q5 Master Mix (New England Biolabs, catalogue no. M0544S), 20 μl of oligonucleotide pool (approximately 20 ng), 0.5 μl of primer mix at a final concentration of 0.5 μM, and 29 μl nuclease-free water. PCR cycling conditions: (1) 98 °C for 30 s; (2) 98 °C for 10 s; (3) 68 °C for 30 s; (4) 72 °C for 30 s; (5) go to (2), eight times; (6) 72 °C for 2 min.

The resulting amplicons were PCR-purified (Zymo, catalogue no. D4060) and cloned into the library vector using Golden Gate cloning with Esp3I (Thermo Fisher Scientific, catalogue no. ER0451) and T7 ligase (New England Biolabs, catalogue no. M0318); the library vector was pre-digested with BsmBI-v2 (New England Biolabs, catalogue no. R0739). The ligation product was electroporated into MegaX DH10B T1R Electrocomp cells (Invitrogen, catalogue no. C640003) and grown at 30 °C for 24 h in 200 ml LB broth with 100 μg ml−1 carbenicillin. Library diversity and sgRNA representation were assessed through PCR amplicon sequencing.

Lentivirus production

Lentivirus was produced in HEK293T cells (Takaro Bio). HEK293Ts were seeded at a density of 80,000 cells cm−2 24 h before transfection. Transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, catalogue no. L3000001) transfection reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After 6 h, the medium was removed and replaced with fresh medium supplemented with 1× ViralBoost (Alstem, catalogue no. VB100). Supernatant was collected at 48 h after transfection and concentrated roughly at 1:100 with lentivirus precipitation solution (Alstem, catalogue no. VC100).

Generation and analysis of scRNA-seq libraries

scRNA-seq library generation

The manufacturer-provided protocol (CG000421 Rev D) was used to generate 10x single-cell gene expression and sgRNA libraries. Samples from several individuals were pooled (Supplementary Table 3) and each 10x lane was loaded with ~100,000 cells in total. sgRNA libraries were amplified separately from each 10x cDNA library using the 10x 3’ Feature Barcode Kit (catalogue no. PN-1000262). To generate STICR barcode libraries, 10 μl of 10x cDNA library was used as template in a 50 μl PCR reaction containing 25 μl Q5 Hot Start High Fidelity 2× master mix (NEB, catalogue no. M0494) and STICR barcode read 1 and 2 primers (0.5 μM, each) described in Delgado et al.1 using the following program: 1, 98 °C, 30 s; 2, 98 °C, 10 s; 3, 62 °C, 20 s; 4, 72 °C, 10 s; 5, repeat steps 2–4 15 times; 6, 72 °C, 2 min; 7, 4 °C, hold. A 0.8–0.6 dual-sided size selection was performed using SPRIselect Bead (Beckman Coulter, catalogue no. B23318) after PCR amplification.

For the ARX, LMO1 dKD experiment, cells are captured with Illumina Single Cell CRISPR Prep (T10, catalogue no. 20132435) where direct sgRNA capture was enabled. Gene expression and sgRNA libraries were prepared following the manufacturer-provided protocol (FB0004762; FB0002130).

Alignments and quality control

Libraries were sequenced on Illumina NovaSeq platforms to the depth of roughly 20,000–30,000 reads per cell for gene expression and 5,000 reads per cell for sgRNA and STICR libraries. Data were acquired using Illumina sequencer control software and bcl2fastq software.

The 10x gene expression libraries, together with sgRNA and STICR libraries, were aligned to the hg38 genome obtained from CellRanger (refdata-gex-GRCh38-2024-A) with feature barcode reference (Supplementary Table 2) using CellRanger v.7.2.0. Aligned counts were then processed with Cellbender108 for ambient removal. The resulting counts were processed by Scanpy109 to remove low quality cells containing fewer than 1,000 genes, a high abundance of mitochondrial reads (greater than 15% of total transcripts) or a high abundance of ribosomal reads (greater than 40% of total transcripts). Illumina single-cell CRISPR libraries were aligned using DRAGEN single-cell RNA v.4.4.5 with additional arguments –single-cell-barcode-tag and –single-cell-umi-tag to support downstream individual demultiplexing. Low quality cells that had fewer than 500 genes or high abundance of mitochondrial or ribosomal reads were removed.

To align 10x runs with pooled human and rhesus macaque individual samples (Supplementary Table 3), we made a composite genome using CellRanger mkref function with (1) hg38 (CellRanger refdata-gex-GRCh38-2024-A) and (2) a version of rheMac10 included in a hierarchical alignment and annotated with the Comparative Annotation Toolkit110 as part of ref. 111, then filtered with litterbox (https://github.com/nkschaefer/litterbox). Cells identified as cross-species multiplets were removed from downstream analyses.

Demultiplexing of individuals from pooled sequencing and doublet removal

CellSNP-lite followed by Vireo112,113 were used to identify different individuals based on reference-free genotyping using candidate SNPs identified from 1000 Genome Project. Sex information was acquired through PCR-based genotyping using genomic DNA extracted from each person. Each person was assigned based on sex and pooling information (Supplementary Table 3). The same individuals from different 10x lanes were merged based on identical SNP genotypes. Inter-individual doublets and unassigned cells were removed from downstream analyses.

sgRNA and lineage barcode assignments

Cellbouncer114 was used for sgRNA assignment using the sgRNA count matrix obtained from CellRanger. ‘effective_sgRNA’ was defined for each cell based on assigned sgRNAs after collapsing NT sgRNA. For example, cells assigned with NT sgRNA and SOX2-targeting sgRNA are classified as ‘effective_sgRNA’=SOX2. ‘Target_gene’ was defined for each cell based after collapsing NT sgRNA and sgRNAs sharing the same target genes. For example, cells infected with two different SOX2-targeting sgRNAs are classified as ‘Target_gene’=SOX2 and included for analysing SOX2 KD phenotypes at the gene level. Multi-infected cells with sgRNAs targeting different genes were assigned to have more than one ‘Target Gene’ and removed from downstream analyses.

KD efficiency in the initial screen was calculated in each cell class following the DEseq2 (ref. 115) workflow, where single-cell data were pseudobulked by cell class per sgRNA per individual. We reasoned that KD efficiency can vary between cell types and classes depending on the baseline expression level of the target gene, and that KD effects may be difficult to detect in cell types with low baseline expression. log2FC output by the DEseq2 Wald test was obtained in each cell class and the lowest log2FC among cell classes was used for visualization and downstream filtering (Supplementary Table 4). sgRNAs that had KD efficiency less than 25% (log2FC > −0.4, 18 sgRNAs) were considered inactive and excluded from downstream analyses. KD efficiency at the gene level was calculated pseudobulking each supervised cell type per TF per gene per individual after collapsing all active sgRNAs targeting the same gene. Pearson correlation coefficients comparing log2FC of DEGs (DEseq2 Wald test, Benjamini–Hochberg-adjusted P < 0.05) at the sgRNA level and at the gene level were calculated to evaluate variabilities between sgRNAs.

STICR barcodes for lineage tracing experiments were aligned and assigned using a modified NextClone116 workflow that allows for whitelisting. The pipeline is available at https://github.com/cnk113/NextClone. Individual barcodes were filtered by at least three reads supporting a single unique molecular identifier and at least two unique molecular identifiers to call cells with a barcode. Clone calling was done using CloneDetective116.

Comparison with public datasets and cell-type annotation

The processed developing human cortex multiomic dataset, including metadata and aligned CellRanger output, was obtained from ref. 12 and used for reference mapping. The reference model was built with scvi-tools117 using the top 2,500 variable genes, and label transfer to query datasets generated in this study was performed for data integration and to examine correspondence of cell-type assignment to the reference dataset. Cell-type annotation in the initial human screen generated in this study was performed based on marker expression as well as scANVI predictions. The initial human screen dataset was then used as a reference dataset to map other 2D populations collected from lineage-resolved targeted screen in human and rhesus macaque, and the ARX, LMO1 dKD experiment to minimize impacts of batch effects and species differences on cell-type annotation.

Public datasets of processed single-cell RNA-seq from iNeuron53, FeBO54 and iPS-cell-derived organoid55 studies were used to compare fidelity of in vitro specified cell types across different systems. Reference mapping and label transfer to the ref. 12 in vivo dataset were performed to examine correspondence to the in vivo cell types. Pearson correlation coefficients per cell type between datasets were calculated using expression of the top 25 markers identified from the in vivo dataset to compare the fidelity of cell identities. To assess the level of cellular stress, gene scores for glycolysis, endoplasmic reticulum stress, reactive oxygen species (ROS), apoptosis and senescence were calculated using the score_genes function in Scanpy with gene sets obtained from the MSigDB database118,119. NT control cells of all cell types were subset from data obtained in this study for this comparison. Each dataset was then downsampled randomly to 5,000 cells to ensure balanced representation between datasets.

Trajectory analysis using pseudotime and RNA velocity

The initial human screen data was subset to NT cells for pseudotime and RNA velocity inference. Pseudotime was calculated using scFates120 by tree learning with SimplePPT and setting the root node within the RG class on ForceAtlas2 embedding. Excitatory and inhibitory trajectories were defined as main branches of the principal graph that led to distinct sets of clusters. The velocyto121 pipeline was implemented to quantify spliced and unspliced reads from CellRanger output. Highly variable genes were separately calculated using spliced and unspliced matrices and the top 3,000 genes were used for inferring RNA velocity using scVelo122.

Differential composition and gene expression analysis

Cells with single ‘Target_gene’ were subset and sgRNAs targeting the same gene were collapsed for downstream analyses at the gene level. Composition changes in each cluster per TF perturbation were quantified using DCATS123, which detects differential abundance using a beta-binomial generalized linear model model and returns the estimated coefficients and likelihood ratio test P values. To detect compositional changes in a finer resolution, Milo76 was used to quantify differential abundance in a label-free manner. Briefly, perturbed and/or NT cells were downsampled randomly to ensure the balance of total cell numbers between the two groups. Neighbourhoods were constructed based on k-nearest-neighbour graphs, and differential cell abundance in each neighbourhood was then tested against NT using design = ~stage + sex + batch + perturbation. Robustness to downsampling was tested in four perturbations through downsampling randomly to 200–600 cells.

Cluster-aware differential gene expression analysis was performed following the DEseq2 (ref. 115) pipeline using NT cells as reference and individual as replicates. When pseudobulking within cell types, conditions that have fewer than five cells per cell type or fewer than two biological replicates were removed from downstream analyses. DEGs (DEseq2 Wald test, Benjamini–Hochberg-adjusted P < 0.05) identified under more than one perturbation across 44 TFs perturbations at the gene level in the initial human screen were defined as ‘convergent DEGs’ and gene ontology enrichment analysis was performed using non-convergent DEGs as background with richR (https://github.com/guokai8/richR). One-sided Fisher’s exact test was performed to identify significant overlap between convergent DEGs and seven sets of disease-associated genes (see below) using non-convergent DEGs as background.

To prioritize TFs whose repression led to strongest cellular and transcriptional and consequences in the initial human screen, |estimated coefficient| from DCATS and numbers of DEGs from DEseq2 across seven cell types in the EN and IN lineage (RG_DIV, RG-Astro, IPC_EN, EN_ImN, EN, IPC_IN, IN) were summed to quantify accumulated effects of TF repression in composition and gene expression, respectively. To test the robustness of prioritized TFs, scCoda124 was applied to estimate log2FC in cell abundance per cell type. Euclidean and energy distance between each TF perturbation were calculated with Pertpy125 to compare the global transcriptional landscape post perturbation.

The DCATS and DEseq2 pipeline described above was also implemented in the datasets generated in lineage-resolved targeted screens in human and macaque 2D culture and in human organotypic slice culture to compare results between batches, cultural systems and species, and to support robustness and reproducibility of the phenotypes reported.

Disease-associated genes from previous studies

Genes significantly associated with neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders were obtained from:

-

ASD: SFARI gene database85, score 1

-

NDD: Supplementary Table 11 in ref. 86

-

MDD: Supplementary Table 9 in ref. 126

-

SCZ: Supplementary Table 12 in ref. 127

-

BP: Supplementary Table 4 in ref. 128

-

ADHD: Supplementary Table 7 in ref. 129

-

AD: Supplementary Table 5 in ref. 130

Lineage coupling and clonal clustering

Clones with fewer than three cells and clones that have conflicted sgRNA assignments were removed from the clonal analysis to consider only multicellular clones generated post infection. One human individual (GW17 187-M) with overall low cellular coverage was dropped from the subsequent analyses. Cospar88 was used to calculate the fate coupling scores per perturbation, defined as the normalized barcode covariance between different cell types.

scLiTr89 was used to identify and cluster fate biased clones by training a neural network to predict clonal labels of nearest neighbours for each clonally labelled cell. To minimize batch effects in cluster identification, we used integrated lineage-resolved data to define five clusters with distinct fate biases. The results obtained were exported and a two-sided paired Wilcoxon test was performed comparing the mean fractions of clonal clusters per TF perturbation against NT. Wilcoxon rank sum test through Scanpy was used to identify marker genes in the RG class (RG-Astro and RG_DIV) between different clonal clusters in human. Monocle3 (ref. 131) was used to construct pseudotime trajectory at the clonal level per species. The median pseudotime per individual was calculated under each perturbation and used for two-sided paired Wilcoxon tests to evaluate the changes on clonal pseudotime. To fit gene expression along the clonal pseudotime, cells in the RG class from multicellular clones were subset and assigned with pseudotime values based on their clone identities.

IN subtype identification and gene expression analysis

To identify IN subtypes, the IN cluster from the initial human screen was subset and re-clustered into six subtypes, each expressing distinct markers identified through Scanpy using Wilcoxon rank sum test. Reference mapping and label transfer were then performed querying INs generated in the lineage-resolved human and macaque datasets and the dKD dataset to identify equivalent clusters. For cell abundance testing in IN subtypes in each perturbation, NT and perturbed INs were downsampled and the Milo pipeline described above was applied to identify differential abundance within the IN cluster. Differential expression analysis was performed using DEseq2 contrasting the IN_LMO1/RIC3 cluster with other physiological subtypes identified in unperturbed INs (IN_NFIA/ST18, IN_PAX6/ST18, IN_CALB2/FBN2, IN_PBX3/GRIA1) in each species, using individuals as replicate. Gene ontology terms enrichment in biological processes in the human IN_LMO1/RIC3 cluster were identified using pathfindR132 (one-sided hypergeometric test).

To survey physiological counterparts of the IN_LMO1/RIC3 cluster, an in vivo atlas of the developing macaque telencephalon96 was used as reference and label transfer using scvi-tools was performed to map INs generated in the targeted 2D screen. Gene scores for glycolysis, endoplasmic reticulum stress, ROS, apoptosis and senescence were calculated in INs per perturbation as described above to assess changes in cellular stress induced by TF perturbation.

Comparison with organotypic slice culture dataset

The lineage-resolved targeted screen dataset in human organotypic slice culture was preprocessed as described above. Cell-type annotation was done based on marker gene expression and reference mapping to the ref. 12 atlas. Only cells derived from multicellular clones were included for visualizing cell-type compositions per TF perturbation to consider the effects on dividing progenitors.

Four IN clusters, including those derived from RG in vitro (IN_local) and those labelled post-mitotically (IN_MGE, IN_CGE,IN_OB), were used to compare the pre- and post-mitotic effects of ARX KD on IN gene expression and subtype specification using Milo and DEseq2 as described above. IN_local was used for iterative clustering to identify IN subtypes described in 2D and compare between perturbations.

ARX and LMO1 dKD

A GFP expressing CRISPRi library targeting LMO1 and NT controls, together with an mCherry-expressing vector targeting ARX, were used to achieve dKD and double infected cells expressing both colours were sorted and captured with Illumina Single Cell CRISPR Library Kit. The resulting library was aligned with DRAGEN Single Cell RNA v.4.4.5, reference mapped to the initial human screen data and integrated with previous data from the targeted human screen. sgRNA assignment was done using cellbouncer and double infected INs (ARX, LMO1 dKD or ARX, NT KD) were used for downstream analysis. Differential gene expression in INs was performed using the DEseq2 Wald test by contrasting ARX, LMO1 dKD against ARX KD. Cluster-free differential abundance testing was performed using Milo after integrating with previous batches to compare differential abundance of IN subtypes in NT, ARX KD and dKD.

Ethics and inclusion statement

All studies were approved by UCSF GESCR (Gamete, Embryo, and Stem Cell Research) Committee.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.