Expression and purification of LetAB

Plasmid pBEL1284, which encodes N-terminal 6×His2xQH-TEV-tagged LetA and untagged LetB, was transformed into OverExpress C43 (DE3) cells (60446-1, Lucigen; Supplementary Table 1). For protein expression, overnight cultures (LB, 100 µg ml−1 carbenicillin and 1% glucose) were diluted in LB (Difco) supplemented with carbenicillin (100 µg ml−1), grown at 37 °C with shaking to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of approximately 0.9, and then induced by addition of arabinose to a final concentration of 0.2%. Cultures were further incubated at 37 °C with shaking for 4 h, and then harvested by centrifugation. The pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl and 10% glycerol), flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. Cells were lysed by two passes through an Emulsiflex-C3 cell disruptor (Avestin), then centrifuged at 15,000g for 30 min at 4 °C to pellet cell debris. The clarified lysate was subjected to ultracentrifugation at 37,000 rpm (182,460g) for 45 min at 4 °C in a Fiberlite F37L-8 ×100 Fixed-Angle Rotor (096-087056, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The supernatant was discarded and the membrane fraction was solubilized in 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 25 mM n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (DDM) by rocking overnight at 4 °C. Insoluble debris were pelleted by ultracentrifugation at 37,000 rpm for 45 min at 4 °C. Solubilized membranes were then passed twice through a column containing Ni Sepharose Excel resin (Cytiva). Eluted proteins were concentrated using an Amicon Ultra-0.5 Centrifugal Filter Unit concentrator (MWCO 100 kDa, UFC510096) before separation on the Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 column (Cytiva) equilibrated with either Tris (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM DDM and 10% glycerol) or HEPES (20 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM DDM and 10% glycerol) gel-filtration buffer. Fractions containing LetAB were pooled, concentrated and applied to grids for negative-stain electron microscopy or cryo-EM. One litre of culture typically yields 30–40 µg of the LetAB complex.

Negative-stain electron microscopy

To prepare grids for negative-stain electron microscopy analysis, a fresh sample of LetAB was applied to a freshly glow-discharged (30 s) carbon-coated 400 mesh copper grid (01754-F, Ted Pella) and blotted off. Immediately after blotting, 3 µl of a 2% uranyl formate solution was applied for staining and blotted off on filter paper (Whatman 1) from the opposite side. Application and blotting of stain was repeated four times. The sample was allowed to air dry before imaging. A negative-stain grid of the soluble, periplasmic domain of LetB was prepared previously31 using a similar procedure and stored. New images from this sample were acquired for this study. Data were collected on the Talos L120C TEM (FEI) equipped with the 4K × 4K OneView camera (Gatan) at a nominal magnification of ×73,000 corresponding to a pixel size of 2.03 Å px−1 on the sample and a defocus range of −1 to −2 μm. Negative-stain dataset size was determined to be sufficient by the ability to see features in the 2D classes of picked particles. For both the LetAB and LetB datasets, micrographs were imported into cryoSPARC (v3.3.1)54 and approximately 200 particles were picked manually, followed by automated template-based picking. Particles were extracted with a 320 pixel box size. Several rounds of 2D classification were performed using default parameters, except that ‘force max over poses/shifts’ and ‘do CTF correction’ were both set to false.

Cryo-EM sample preparation and data collection

To generate the crosslinked LetAB sample, 1% glutaraldehyde was added to purified LetAB (HEPES gel-filtration buffer) at a final concentration of 0.025%. The sample was incubated on ice for 1 h and then quenched by the addition of 75 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0. The sample was incubated for 15 min on ice before filtering using an Ultrafree centrifugal filter (UFC30GVNB) and loading onto a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 column (Cytiva), equilibrated with buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl and 0.5 mM DDM, to remove aggregated LetAB. Fractions containing the LetAB complex were concentrated to 1 mg ml−1 using the Amicon Ultra-0.5 centrifugal filter unit concentrator (MWCO 100 kDa, UFC510096). Continuous carbon grids (Quantifoil R 2/2 on Cu 300 mesh grids + 2 nm Carbon, Quantifoil Micro Tools, C2-C16nCu30-01) were glow-discharged for 5 s in an easiGlow Glow Discharge Cleaning System (Ted Pella). Of freshly prepared sample, 3 µl was added to the glow-discharged grid. Grids were prepared using a Vitrobot Mark IV (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Grids were blotted with a blot force of 0 for 3 s at 4 °C with 100% chamber humidity and then plunge-frozen into liquid ethane. Grids were clipped for data acquisition.

Grids containing crosslinked LetAB were screened at the NYU cryo-EM core facility on the Talos Arctica (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with a K3 camera (Gatan). The grids were selected for data collection on the basis of ice quality and particle distribution. The selected cryo-EM grid was imaged on two separate sessions at the Pacific Northwest Center for Cryo-EM (PNCC) on Krios-1, a Titan Krios G3 electron microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with a K3 direct electron detector with a BioContinuum energy filter (Gatan). Super-resolution movies were collected at 300 kV using SerialEM55 at a nominal magnification of ×81,000, corresponding to a super-resolution pixel size of 0.5144 Å (or a nominal pixel size of 1.029 Å after binning by 2). Movies (n = 12,029) movies were collected over a defocus range of −0.8 to −2.1 µm, and each movie consisted of 50 frames with a total dose of 50 e− Å−2. Further data collection parameters are shown in Extended Data Table 1.

The uncrosslinked LetAB complex was prepared as described in ‘Expression and purification of LetAB’, except the Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 column was equilibrated in buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl and 0.5 mM DDM. Continuous carbon grids (Quantifoil R 2/2 on Cu 300 mesh grids + 2 nm Carbon, Quantifoil Micro Tools, C2-C16nCu30-01) were glow-discharged for 5 s in an easiGlow Glow Discharge Cleaning System (Ted Pella). Of freshly prepared sample (1 mg ml−1) in Tris gel filtration buffer, 3 µl was added to the glow-discharged grid. Grids were prepared using a Vitrobot Mark IV (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Grids were blotted with a blot force of 0 for 3 s at 4 °C with 100% chamber humidity and then plunge-frozen into liquid ethane. Grids were clipped for data acquisition. Grids were screened at the NYU cryo-EM laboratory on the Talos Arctica (Thermo Fisher Scientific) system equipped with a K3 camera (Gatan). The grid with the best ice quality and particle distribution was imaged at the New York Structural Biology Center on Krios-1, a Titan Krios G3 electron microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with K3 direct electron detector with a BioContinuum energy filter (Gatan). Super-resolution movies were collected at 300 kV using Leginon56 at a nominal magnification of ×81,000, corresponding to a super-resolution pixel size of 0.5413 Å (or a nominal pixel size of 1.083 Å after binning by 2). Movies were collected over a defocus range of −2 to −5 µm, and each movie consisted of 40 frames with a total dose of 51 e− Å−2. A total of 12,455 movies were collected, consisting of 5,372 movies at 0° tilt and 7,083 movies at −30° tilt. Further data collection parameters are shown in Extended Data Table 2.

Cryo-EM structure of crosslinked LetAB

The data processing workflow for the crosslinked LetAB sample is shown in Supplementary Fig. 2e. A combination of cryoSPARC (v3.2.0–4.3.0) and RELION (v3.1.0)57 were used for data processing. Dose-fractionated movies were gain normalized, drift corrected, summed and dose weighted, and binned by 2 using the cryoSPARC Patch Motion module. Contrast transfer function (CTF) estimation for each summed image was carried out using cryoSPARC Patch CTF estimation. To generate 2D templates for auto-picking, 1,003 particles were manually picked, extracted (box size of 576 px) and subjected to 2D classification. The classes with top, tilted and side views of LetAB were selected as templates for auto-picking, which yielded 3,582,925 particles after extraction (box size of 576 px). The particles were subjected to 2D classification (200 classes) with force max over poses/shifts set to false. Well-aligned 2D classes were selected (1,793,362 particles) and a 3D reconstruction was generated using ab initio reconstruction. The 3D reconstruction was used as a template for 3D refinement in RELION, which revealed well-resolved density for MCE rings 1–4, poor and noisy density for MCE rings 5–7 and no density for LetA, probably due to rings 1–4 dominating the particle alignment. To improve resolution for LetA, local refinement was performed using a mask around LetB rings 1–4 and the TM region, followed by particle subtraction in RELION where the signal for the TM region and rings 1–2 was kept and recentred to the middle of the box (256 px). The subtracted particles were imported into cryoSPARC, where reference-free 3D classification was performed using the ab initio module (two classes) to remove misaligned and ‘junk’ particles. This resulted in one class with 1,171,725 particles with high-resolution features. The particles from this class were further cleaned using 2D classification and then subjected to non-uniform refinement (942,263 particles). The aligned particles were imported into RELION and sorted using 3D classification without alignment (eight classes), which revealed one class containing density for the TM region with high-resolution features. The particles (158,666) were then subjected to local refinement in RELION, yielding a map (Map 1a) with a nominal resolution of 3.4 Å (Supplementary Fig. 2b).

To obtain high-resolution maps of MCE rings 2–4 and MCE rings 5–7, the 1,793,362 particles from the initial 2D classification step were Fourier cropped to a box size of 128 px. The particles were sorted using heterogeneous refinement (five classes) in cryoSPARC, which revealed only one class where LetB is straight rather than curved. The particles from this class (448,403) were re-extracted (box size of 512 px), aligned using non-uniform refinement and imported into RELION. The aligned particles underwent local refinement, followed by particle subtraction to yield signal for either MCE rings 2–4 or MCE rings 5–7. During particle subtraction, the subtracted images were recentred to the middle of the box, which was cropped to either 360 px (MCE rings 2–4) or 256 px (MCE rings 5–7). The two particle-subtracted stacks were imported into cryoSPARC, where the particles were subjected to reference-free 3D classification using ab initio reconstruction (three classes) to remove misaligned and ‘junk’ particles. The particles from the selected class were aligned using non-uniform refinement, and then imported into RELION for 3D classification without alignment (eight classes). The classes with the highest resolution features were selected, their particles combined before being imported into cryoSPARC for non-uniform refinement to improve the densities for both the MCE core domains and the pore-lining loops31, resulting in Map 1b (rings 2–4) and Map 1c (rings 5–7). All refinement steps were performed without symmetry applied (C1).

During the model-building process, initial reports describing AlphaFold2 (ref. 58) and RoseTTAFold59 became public. To accelerate model building for LetAB, RoseTTAFold59 was used to predict the 3D structure of LetA. The model was fit as a rigid body into the LetA density in Map 1a, followed by rigid body fitting of TMDN (amino acids 66–218), TMDC (amino acids 261–418), ZnRN (amino acids 24–65) and ZnRC (amino acids 219–261). Residues 1–26 and 419–427 were deleted due to the absence of density for them. As our ICP-MS data suggest LetA binds to zinc, we used Coot (v0.8.9.2)60 to add zinc ligands to the densities found in between the predicted metal-coordinating cysteines. To build the model for MCE rings 1–2, PDB 6V0J was used as a starting model, as it best matches the density in Map 1a. The model was first fit as a rigid body into the density corresponding to LetB, followed by rigid body fitting of each MCE domain. The pore-lining loops of MCE ring 1 exhibit C3 symmetry. Densities for four out of six TM helices of LetB were observed, and those helices were manually built using Coot. Residues (25–45) of a LetB TM helix (chain B) were stubbed due to the lack of side-chain density.

For Maps 1b and 1c, PDB 6V0F and PDB 6V0E, respectively, best fit into the density after rigid body docking. Each MCE domain was rigid-body fit into the density. The pore-lining loops of rings 5 and 6 exhibit C3 symmetry. Extra densities that do not correspond to the protein are present near the pore-lining loops between rings 5–6 and rings 6–7, but the resolution is too low to determine the identity of the ligand. Therefore, ligands were not modelled into these densities. It is possible that these densities represent non-native ligands, such as DDM from the sample buffer. Each model was real space refined into its respective map using PHENIX61 with global minimization, Ramachandran, secondary structure and ligand restraints. Using UCSF Chimera62, Maps 1a and 1c were fit into map 1b and resampled such that the maps overlaid with one another. These maps were then used to stitch together the models. The MCE ring 2 model from map 1b (instead of the one from map 1a) was used to generate the composite model as this map had complete density for MCE ring 2. The resulting composite model was used as a template to generate a composite density map (map 1) using the PHENIX Combine Focused Maps module. The model was real space refined into map 1 using PHENIX with global minimization, Ramachandran, secondary structure and ligand restraints.

For validation, statistics regarding the final models (Extended Data Table 1) were derived from the real_space_refine algorithm of PHENIX and MolProbity63, EMRINGER64 and CaBLAM65 from the PHENIX package61 were used for model validation. Directional Fourier shell correlations (FSCs) were computed using 3DFSC66. Model correlations to our electron microscopy maps were estimated with correlation coefficient (CC) calculations and map model FSC plot from the PHENIX package.

We used this model to assess the conformation of the LetB MCE rings via CHAP67. MCE rings 3, 5 and 6 are in a single, closed conformation, whereas the conformation of rings 2, 4 and 7 could not be reliably assessed due to weak density for the pore-lining loops (Extended Data Fig. 1g). However, as the different segments of LetB were processed separately (Supplementary Fig. 2a), it is unclear if the conformations of rings 1, 3, 5 and 6 are correlated.

Cryo-EM structure of uncrosslinked LetAB

Data processing workflow for the uncrosslinked LetAB sample is shown in Supplementary Fig. 3e. A combination of cryoSPARC (v3.3.1–4.3.0) and RELION (v4.0-beta) were used for data processing. Particle picking was performed in RELION on the motion-corrected micrographs generated by the New York Structural Biology Center using MotionCor2 (ref. 68). 2D templates were generated for auto-picking on manually picked particles. The particles (3,014,365 at 0° tilt; 3,960,481 at −30° tilt) were imported into cryoSPARC and re-extracted (600 px, Fourier cropped to 100 px) from Patch CTF-corrected micrographs generated within CryoSPARC (gain normalized, drift corrected, summed, binned 2× and dose weighted using the cryoSPARC Patch Motion module). The particles underwent several rounds of 2D classification (200 classes) with force max over poses/shifts set to false. Well-aligned 2D classes were selected, resulting in 1,582,691 particles at 0° tilt and 1,918,023 particles at 30° tilt. The particles were combined, sorted by 2D classification, and the selected particles were re-extracted (512 px). The particles (2,658,362) were then aligned by non-uniform refinement (C6 symmetry applied) and imported into RELION, where they were subjected to local refinement with C6 symmetry relaxation applied. The signal for MCE rings 2–7 was removed using the Particle Subtraction module. The subtracted images were recentred so that the signal for LetA + MCE rings 1–2 was in the middle of the box, which was cropped to 256 px. The subtracted particles were imported into cryoSPARC and sorted by several rounds of 2D classification (200 classes) to remove misaligned and ‘junk’ particles. The particles were further sorted using the ab initio reconstruction (five classes, three rounds) to yield 1,131,012 ‘clean’ particles, which were then aligned using non-uniform refinement. The particles were imported into RELION for 3D classification without alignment and with a mask around LetA, which revealed a class showing high-resolution features. The particles were imported into cryoSPARC for non-uniform refinement. To continue filtering out low-resolution particles, the particles were sorted by 3D classification without alignment in RELION, followed by non-uniform refinement in cryoSPARC, two additional times. After non-uniform refinement, the particles underwent local refinement in cryoSPARC to yield a map with a nominal resolution of 3.4 Å (Map 2a; Supplementary Fig. 3b).

To obtain high-resolution maps of MCE rings 2–4 and MCE rings 5–7, the 2,658,362 particles from the initial 2D classification step were sorted using heterogeneous refinement (five classes), which revealed only one class where LetB is straight rather than curved. The particles from this class (738,470) were aligned using non-uniform refinement with symmetry applied, and imported into RELION. The aligned particles underwent local refinement, followed by particle subtraction to yield signal for either MCE rings 2–4 or rings 5–7. During particle subtraction, the subtracted images were recentred to the middle of the box, which was cropped to either 360 px (MCE rings 2–4) or 256 px (MCE rings 5–7). The two particle-subtracted stacks were imported into cryoSPARC, where the particles were sorted using ab initio reconstruction (three classes) to remove misaligned and ‘junk’ particles. The classes with high-resolution features were selected and the particles were aligned using non-uniform refinement, and then imported into RELION for 3D classification without alignment (eight classes). The classes with the highest resolution features were selected, their particles combined and imported into cryoSPARC for non-uniform refinement to improve the densities for both the MCE core domains and the pore-lining loops31, resulting in Map 2b (MCE rings 2–4) and Map 2c (MCE rings 5–7).

The crosslinked LetAB model was used to build the model for uncrosslinked LetAB. LetA was rigid body fit into the LetA density in Map 2a. An additional ‘wishbone’-shaped density was observed in the central cavity of LetA that is consistent with the size and shape of a diacyl phospholipid. A similar density is observed in the crosslinked structure, but it is less well resolved, possibly due to the sample undergoing an additional size-exclusion step that resulted in decreased lipid occupancy or due to glutaraldehyde altering the binding site. Because the density was insufficient to unambiguously assign the head group structure and fatty acid chain lengths, we modelled this density as 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (PDB ligand PEF, PE 16:0/16:0), which is an abundant phospholipid species in the E. coli inner membrane. Atoms not well accommodated in the observed density were pruned from the ligand. The MCE ring 1 model from Map 1a was rigid body docked into Map 2a. The individual MCE domains were then rigid body fit into the map. The model was real space refined into Map 2a using PHENIX with global minimization, Ramachandran, secondary structure and ligand restraints. To build a model for rings 2–4 and rings 5–7, the models from Map 1b and Map 1c were rigid body fit into Map 2b and Map 2c, respectively. Each MCE domain was rigid body fit into the map. LetB residues 614–619 were deleted from the model due to poor density in the map. Similar to the crosslinked LetAB model, the pore-lining loops of rings 1, 5 and 6 exhibit C3 symmetry. Extra densities are present near the pore-lining loops between MCE rings 5–6 and rings 6–7. As the resolution is too low to determine the identity of the ligand, the extra densities were left unmodelled. Each model was real space refined into its respective map using PHENIX with global minimization, Ramachandran, secondary structure and ligand restraints. Using UCSF Chimera, Maps 2a and 2c were fit into Map 2b and resampled such that the maps overlaid with one another. These maps were then used to stitch together the models. The MCE ring 2 model from Map 2b was used to generate the composite model as this map had complete density for MCE ring 2. The resulting composite model was used as a template to generate a composite density map (Map 2) using the vop command in ChimeraX. The model was refined using Phenix.real_space_refine into Map 2 with global minimization, Ramachandran, secondary structure and ligand restraints.

For validation, statistics regarding the final models (Extended Data Table 2) were derived from the real_space_refine algorithm of PHENIX and MolProbity63, EMRINGER64 and CaBLAM65 from the PHENIX package61 were used for model validation. Directional FSCs were computed using 3DFSC66. Model correlations to our electron microscopy maps were estimated with CC calculations and map model FSC plot from the PHENIX package.

The overall backbone conformation of LetA is similar in both structures (root mean square displacement (RMSD) of 0.787 Å across 3,123 atoms). For LetB, the overall backbone conformation is also similar in both structures (RMSD of 2.28 Å across 38,379 atoms; Extended Data Fig. 1e). The main difference is that in the crosslinked complex, the distance between each ring in MCE rings 3–7 is shorter relative to their positions in the uncrosslinked LetAB structure. This difference may be an effect of glutaraldehyde crosslinking or reflect fluctuations in the LetB structure that occur in the periplasm.

Sequence alignment

LetA and PqiA proteins are widespread across Proteobacteria. Using the E. coli LetA sequence, we performed a protein BLAST to search for LetA and PqiA proteins across the orders within each of the five classes of Proteobacteria. Only sequences that contained both LetA modules were considered. We then performed a tblastn search using the core nucleotide database and the specified organism to determine whether the gene is in an operon with letB or pqiB, which would indicate whether the query sequence is a letA or pqiA gene, respectively. LetB and PqiB can be identified based on sequence length and AlphaFold2 prediction; LetB has six, seven or eight MCE domains, whereas pqiB has three. Through this method, we identified 20 sequences, in which 9 are LetA and 11 are PqiA proteins. The LetA sequences are from Gammaproteobacteria, whereas PqiA are from Alphaproteobacteria and Betaproteobacteria. The sequences were aligned using MUSCLE (v3.8.31)69 and annotated using Jalview (v2.11.3.3)70.

To generate a sequence alignment for LetB proteins, we performed a protein BLAST to search for sequences across the orders of Gammaproteobacteria. We then performed a tblastn search using the core nucleotide database and the specified organism to determine whether the gene is in an operon with letA. The resulting 20 sequences correspond to structures containing 6, 7 or 8 MCE rings and were aligned using MUSCLE69. This alignment was used to generate a sequence logo using WebLogo3. The Uniprot IDs used to generate the sequence alignment are: P76272 (E. coli), A0A4Y5YG70 (Shewanella polaris), A0A1N7PAF3 (Neptunomonas antarctica), A0A5C6QK63 (Colwellia hornerae), A0A4P6P630 (Litorilituus sediminis), A0A7W4Z577 (Litorivivens lipolytica), A0A4P7JQ50 (Thalassotalea sp. HSM 43), A0A1Q2M9J7 (Microbulbifer agarilyticus), A0A2R3ITY9 (P. aeruginosa), A0A2Z3I1J2 (Gammaproteobacteria bacterium ESL0073), A0A090IGL8 (Moritella viscosa), A0A0X1KWU0 (Vibrio cholerae), Q6LQU6 (Photobacterium profundum), P44288 (Haemophilus influenzae), A0A2U8I7C7 (Candidatus Fukatsuia symbiotica), A0A085GCR5 (Buttiauxella agrestis), A0A8E7UPQ1 (Salmonella enterica), A0A8H8Z9P5 (Shigella flexneri), D4GG77 (Pantoea ananatis) and B2VJ84 (Erwinia tasmaniensis).

DMS

A library containing all the possible single amino acid mutants in LetA (n = 8,540) was synthesized by Twist Bioscience. Apart from the engineered mutations, these plasmid variants were identical to pBEL2071, which refactored LetA and LetB as two non-overlapping open reading frames, as they overlap by 32 bp in their native genomic context. The WT LetAB plasmid was spiked into the library such that approximately 2.5% of LetA sequences in the input library were WT. Our LetA mutant library was divided into four approximately 325-bp sub-libraries (codons 1–104, 105–208, 209–320 or 321–427) due to Illumina sequencing length limitations. The sub-libraries were then handled independently. Two independent biological replicates of the DMS experiments described below were performed starting from these sub-libraries. A ΔletAB ΔpqiAB strain, bBEL384, was transformed by electroporation with each sub-library and grown overnight at 37 °C in LB containing 200 µg ml−1 carbenicillin. We obtained approximately 2 × 106 colony-forming units (CFU) for each sub-library. For the replicate experiment, approximately 1 × 107 CFU was obtained. The cultures were diluted 1:20 into fresh LB media containing 100 µg ml−1 carbenicillin and 50 µg ml−1 kanamycin and shaken (200 rpm) at 37 °C until OD600 = approximately 1. The cultures were plated on LB (DF0445–07-6, BD Difco) + 100 µg ml−1 carbenicillin (‘no selection’), LB + 100 µg ml−1 carbenicillin + 0.105% LSB (‘selection’), or LB + 100 µg ml−1 carbenicillin + 8% cholate (‘selection’). After overnight incubation on the no selection and selection plates, colonies from each condition were separately scraped and pooled, plasmids were extracted and amplicons were generated by PCR. The amplicons from each sub-library were then pooled in equimolar amounts to generate the no selection and selection samples. The NEBNext Ultra II Library Prep kit (E7645, New England Biologs) was used to generate the library for Illumina MiSeq 2 × 250 paired-end sequencing. Paired-end sequencing data were mapped to a reference WT LetA sequence using the bowtie2 (ref. 71) algorithm (v2.4.1), filtered with samtools (v1.9)72 (flags -f 2 -q 42), and overlapping paired ends were merged into a single sequence with PANDAseq (v2.11)73. Finally, primer sequences used for amplicon amplification were removed using cutadapt (v1.9.1)74. Processed and merged reads were then analysed using custom Python scripts to count the frequency of the LetA variants75. In brief, DNA sequences were filtered by length, removing any sequence larger or smaller than the length of the expected library. Next, sequences were correctly oriented to the proper reading frame and translated to the corresponding protein sequence. Finally, the frequency of each amino acid variant at every position was counted and the counts were normalized to the sequencing depth as read counts per million. Normalized LetA variant counts were then used for calculation of the relative fitness value (\(\Delta \)Eix), which is defined as the log frequency of observing each amino acid x at each position i in the selected versus the non-selected population, relative to the WT amino acid (30). The equation for this calculation is as follows:

$$\Delta E_i^x=\log \left(\fracf_i^x,\mathrmself_i^x,\mathrmunsel\right)-\log \left(\fracf_i^\mathrmWT,\mathrmself_i^\mathrmWT,\mathrmunsel\right)$$

(1)

For cholate selection, we found that the square of the Pearson correlation coefficient (r2) between two biological replicates to be r2 = 0.897 (Extended Data Fig. 4b). For LSB selection, the square of the Pearson correlation coefficient is r2 = 0.786. These coefficients indicate that replicates are in a good agreement with one another. We were able to extract meaningful fitness information for 8,478 of 8,540 variants for cholate and 8,504 of 8,540 variants for LSB. Meaningful fitness information for a mutation could not be extracted if counts were not present in either the unselected or selected dataset. For example, many mutations at position 51 had no sequence coverage due to poor representation of residue 51 mutations in the synthesized library. The relative fitness values exhibited a bimodal distribution, in which the two modes represent the neutral and deleterious mutant groups (Extended Data Fig. 4c). We established a cut-off to identify mutations with relative fitness values that are substantially different from the median (0) by calculating the modified Z-score (Mi)76 for each mutation using equations (2) and (3), where xi is a single data value, \(\tilde\bfx\) is the median of the dataset, and MAD is the median absolute deviation of the dataset:

$$M_i=\frac0.6745(x_i-\tilde\bfx)\mathrmMAD$$

(2)

$$\mathrmMAD=\mathrmmedian\\$$

(3)

As modified Z-scores with an absolute value of greater than 3.5 are potential outliers76, mutations with a Z-score of less than −3.5 and more than 3.5 were considered to be deleterious or advantageous, respectively, to LetA function. For each residue, we calculated a tolerance score based on the number and types of amino acid substitutions that are tolerated. The tolerance scores were calculated by using a modified version of the Zvelebil similarity score77,78, which is based on counting key differences between amino acids. Each mutation is given a starting score of 0.1. For each key difference (that is, ‘small’, ‘aliphatic’, ‘proline’, ‘negative’, ‘positive’, ‘polar’, ‘hydrophobic’ and ‘aromatic), a score of 0.1 is given, such that mutations to dissimilar amino acids (for example, alanine to arginine) contribute more to the score. If the mutation is tolerated based on our modified Z-score cut-off, the score for that particular mutation is added to a starting score of 0.1. For each sequence position, the scores for tolerant mutations were summed, then divided by the maximum score possible. A score of 1.0 therefore indicates full tolerance in that position, a score of 0 denotes no tolerance, and in-between scores suggest different levels of tolerance for that amino acid type. A low tolerance score may indicate that mutations at a given residue position impact LetA transport function, or result in misfolded protein and/or lower protein expression levels.

In the cholate dataset, 3 of the 53 residues with tolerance scores of less than 0.7 do not cluster in the three main groups (ZnRs, polar network and outwards-open pocket). The residues are A128, F141 and A272. In the LSB dataset, 2 of the 37 residues with tolerance scores of less than 0.7 are located outside of the three main clusters: I131 and F141. F141 is considered functionally important in both datasets, but it is unclear what its role is, as this residue appears isolated in the membrane. Residues A272 and I131 interact with residues in the LetB TM helices, potentially stabilizing interactions between LetA and LetB in the membrane. As residue A128 precedes the helical ‘break’ of TM3 in TMDN, this position may only tolerate small hydrophobic residues to maintain the structural integrity of LetA.

Complementation assays

letA-knockout and letB-knockout strains were constructed in the E. coli K-12 BW25113 ΔpqiA background by P1 transduction from corresponding strains of the Keio collection79, followed by excision of the antibiotic resistance cassettes using pCP20 (ref. 80). To test the effect of letA (bBEL620), letB (bBEL621) and letAB (bBEL609) deletion mutants on cell viability, overnight cultures grown in LB were diluted 1:50 into fresh LB without antibiotics. The knockout strains carrying pET17b-letAB (Addgene #175804) or its mutants were grown in the presence of 100 µg ml−1 carbenicillin. Cultures were grown for ≈1.5 h at 200 rpm and 37 °C until reaching an OD600 of approximately 1.0, then normalized to a final OD600 of 1.0 with fresh LB. From these normalized cultures, tenfold serial dilutions in LB were prepared in a 96-well plate, and 1 µl of each dilution was spotted onto plates containing LB agar, or LB agar supplemented with either LSB or sodium cholate. The source of LB agar used influenced the LSB and cholate phenotypes, and our agar was prepared from the following components: 10 g tryptone (211705, Gibco), 10 g NaCl (S3014, Sigma-Aldrich), 5 g yeast extract (212750, Gibco) and 15 g agar (214530, BD Difco) per 1 l of deionized water. Plates were incubated approximately 18–20 h at 37 °C and then imaged using a ChemiDoc XRS+ System (Bio-Rad). Stock solutions of LSB (5% w/v) and sodium cholate (40% w/v; A17074.18, Thermo Fisher) were prepared in deionized water and stored at −80 °C. At least three independent transformants were used to perform replicates for each phenotypic assay.

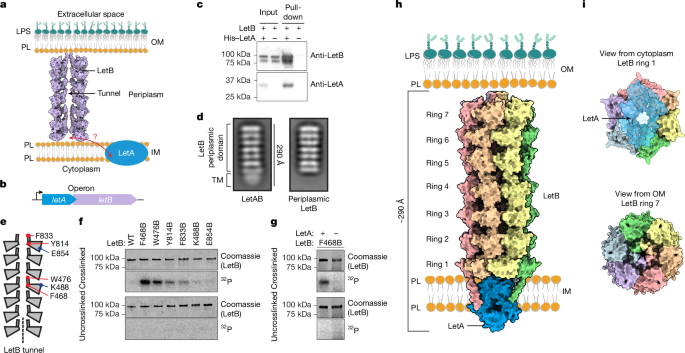

Small-scale pull-down assays

Plasmid pBEL1284 was transformed into OverExpress C43 (DE3) cells (Lucigen). The letA or letB regions were mutated using Gibson assembly. Whole-plasmid sequencing was performed by Plasmidsaurus using Oxford Nanopore Technology with custom analysis and annotation. Overnight cultures (LB, 100 µg ml−1 carbenicillin and 1% glucose) were diluted into 20 ml LB (Difco) supplemented with carbenicillin (100 µg ml−1), grown at 37 °C with shaking to an OD600 of approximately 0.9, and then induced by addition of arabinose to a final concentration of 0.2%. Cultures were further incubated at 37 °C with shaking for 4 h, and then harvested by centrifugation. The pellets were resuspended in 1 ml of lysozyme resuspension buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mg ml−1 lysozyme, 25 U ml−1 benzonase and 1 mM TCEP) and were incubated for 1 h at 4 °C. The cells were lysed with eight cycles of a freeze–thaw method, in which samples are immersed in liquid nitrogen until fully frozen and then thawed in a 37 °C heat block. The lysate containing crude membrane fractions was centrifuged at 20,000g for 15 min, and resuspended in 250 µl of membrane resuspension buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 25 mM DDM and 1 mM TCEP), and shaken for 1 h. The sample volume was then increased to 1 ml with 10 mM imidazole wash buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl and 10 mM imidazole) and insoluble material was centrifuged at 20,000g for 15 min. Each supernatant was then mixed with 25 µl of nickel Ni Sepharose Excel resin (Cytiva) for 30 min. The beads were centrifuged at 500g for 1 min and the supernatant removed. The beads were then washed four times with 40 mM imidazole wash buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 40 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol, 0.5 mM DDM and 1 mM TCEP) and finally resuspended in 50 µl of elution buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 300 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol, 0.5 mM DDM and 1 mM TCEP). The beads were removed by passing through an Ultrafree centrifugal filter (10,000g for 1 min) at 4 °C. The samples were then mixed with 5× SDS–PAGE loading buffer, and analysed by SDS–PAGE and stained using InstantBlue Protein Stain (ab119211, Abcam). Three replicates of the experiment were performed, from independently purified proteins.

To obtain membrane fractions without cell debris, lysed samples were centrifuged at 16,000g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected and the membrane fraction was isolated by ultracentrifugation in a TLA 120.2 rotor (100,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C). The supernatant was removed, the pellet resuspended in 500 µl of membrane resuspension buffer, shaken for 1 h at 4 °C, and 500 µl of 20 mM imidazole wash buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol, 0.5 mM DDM and 1 mM TCEP) was added. The samples were then purified using affinity resin as described above.

Generation of LetA monoclonal antibodies

Plasmid pBEL2214 was transformed into Rosetta (DE3) cells (Novagen) for protein expression, and overnight cultures were grown in LB supplemented with carbenicillin (100 µg ml−1), chloramphenicol (38 µg ml−1) and 1% glucose at 37 °C. The overnight cultures were diluted 1:50 in fresh LB media supplemented with carbenicillin (100 µg ml−1) and chloramphenicol (38 µg ml−1). Upon reaching an OD600 of approximately 0.9, protein expression was induced with the addition of l-arabinose to a final concentration of 0.2%. Cells were cultured for an additional 4 h at 37 °C with shaking, and then harvested by centrifugation. The pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl and 10% glycerol) flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. Cells were lysed by three passes through an Emulsiflex-C3 cell disruptor (Avestin), then centrifuged at 15,000g for 30 min at 4 °C to pellet cell debris. The clarified lysate was subjected to ultracentrifugation at 37,000 rpm (182,460g) for 45 min at 4 °C in a Fiberlite F37L-8 ×100 Fixed-Angle Rotor (096-087056, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and the membrane fraction was solubilized in 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol and 25 mM DDM by rocking overnight at 4 °C. Insoluble debris was removed by ultracentrifugation at 37,000 rpm for 45 min at 4 °C. Solubilized membranes were then passed twice through a column containing Ni Sepharose resin (Cytiva). Eluted proteins were exchanged into low-salt buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.0, 25 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM DDM and 10% glycerol) using an Amicon Ultra-0.5 Centrifugal Filter Unit concentrator (MWCO 30 kDa, UFC503008) before injection into a Mono S 5/50 GL column (Cytiva). The column was eluted using a salt gradient from 25 mM to 1.5 M NaCl over 40 column volumes. The eluted proteins containing LetA were concentrated using an Amicon Ultra-0.5 Centrifugal Filter Unit concentrator (MWCO 30 kDa, UFC503008) before separation in a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 column (Cytiva) equilibrated in gel-filtration buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM DDM and 10% glycerol).

To generate LetA rat monoclonal antibodies, three 6-week-old Sprague Dawley female rats (Taconics) were immunized with purified LetA protein (100 µg per animal per boost for five boosts). Immune response was monitored by ELISA to measure the serum anti-LetA IgG titre from blood samples. After a 60-day immunization course, the rat with the strongest anti-LetA immune response was terminated and 108 splenocytes were collected for making hybridomas by fusing with the rat myeloma cell line YB2/0, following the standard method81. All procedures were approved by the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

To select monoclonal antibodies, supernatants collected from individual hybridoma culture media were screened by ELISA to identify hybridoma clones positive for LetA. Positive hybridoma colonies were then isolated and seeded to establish pure hybridoma clones from single-cell colonies. For ELISA, purified LetA or negative control protein streptavidin diluted in LetA storage buffer (20 mM Tris pH8, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol and 0.5 mM DDM) were coated (50 ng per well) on ELISA plates (464718, Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Before adding the hybridoma supernatant, the coated plate was blocked with LetA storage buffer (20 mM Tris pH8, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol and 0.5 mM DDM) containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) at 4 °C for 6 h. After blocking, hybridoma supernatants diluted in LetA buffer (1:1 dilution) were added to the ELISA plate and incubated at room temperature for 1 h, followed by three times of extensive wash with LetA buffer. The secondary antibody (112-035-003, Jackson ImmunoResearch for anti-rat IgG horseradish peroxidase (HRP)) was then added and incubated at room temperature for 30 min, followed by three times of extensive wash with LetA buffer. Chromogenic binding signal was developed by using 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine ultra as the HRP substrate (34028, Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Data were collected by measuring the absorbance at 450 nm with a plate reader (Cytation 5, Agilent). The ELISA assay revealed 23 antibody clones to be strong binders of LetA, and two were found to detect LetA in cell lysates via western blotting (clones 45 and 72). Clone 45 recognizes an epitope in the ZnR domains, and can also recognize PqiA. The epitope recognized by clone 72 is in the N-terminal extension of LetA, and does not appear to cross-react with PqiA.

Western blotting

To test for protein expression in the strains used for the complementation assays, 5 ml cultures of E. coli strains ΔpqiAB (bBEL385), ΔletAB (bBEL466) and ΔpqiAB ΔletAB (bBEL609) containing each complementation plasmid were grown to an OD600 of approximately 1. For plasmid-containing strains, the cultures were supplemented with carbenicillin (100 µg ml−1). The cells were centrifuged at 4,500g for 10 min and resuspended in 1 ml of freeze–thaw lysis buffer (PBS pH 7.4, 1 mg ml−1 lysozyme and 1 μl ml−1 of benzonase (Millipore)), and incubated on ice for 1 h. The cells were lysed with eight cycles of a freeze–thaw method, in which samples are immersed in liquid nitrogen until fully frozen and then thawed in a 37 °C heat block. After lysis, the cells were centrifuged at approximately 20,000g for 15 min and the pellets were resuspended in 100 μl of SDS–PAGE loading buffer. Each sample (10 μl) was separated on an SDS–PAGE gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane using the Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The membranes were blocked in PBS Tween20 (PBST; 1X PBS + 0.1% Tween20) containing 5% milk for 1 h at room temperature. To probe LetA, the membranes were incubated with primary antibody in PBST + 5% BSA, either rat monoclonal anti-LetA clone 45 or clone 72 at a final concentration of 0.5 µg ml−1 or 2 µg ml−1, respectively. To probe LetB or BamA, membranes were incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-LetB (1:10,000 dilution) in PBST + 5% BSA or rabbit polyclonal anti-BamA31 (1:2,000 dilution) in PBST + 5% BSA, respectively. His-tagged and Strep-tagged proteins were probed using mouse penta-His (1:500 dilution; 34660, Qiagen) and rabbit Strep tag monoclonal (GT661, 1:5,000 dilution; PA5-114454, Thermo Fisher) antibodies, respectively. Membranes were incubated in primary antibody solution for either 2 h at room temperature or overnight at 4 °C with agitation. The membranes were then washed three times with PBST and incubated with goat anti-rat IgG IRDye 680RD (1:5,000 dilution; 926-68076, LI-COR Biosciences), goat anti-rat IgG IRDye 800CW (1:10,000 dilution; 926-32219, LI-COR Biosciences), goat anti-rabbit IgG IRDye 680CW (1:10,000 dilution; 926-68071, LI-COR Biosciences), goat anti-mouse IgG IRDye 680CW (1:5,000 dilution; 926-68070, LI-COR Biosciences) or goat anti-rabbit IgG IRDye 800CW (1:10,000 dilution; 925-32211, LI-COR Biosciences) secondary antibodies in Intercept (TBS) blocking buffer (927-60003, LI-COR Biosciences) for 1 h at room temperature with agitation. The membranes were then washed three times with PBST and imaged on a LI-COR Odyssey Classic.

ICP-MS

Plasmid pBEL1284 was modified to encode only LetA with a C-terminal 2×QH-7×His tag to yield pBEL2214. The plasmid was transformed into Rosetta (DE3) cells (Novagen) for protein expression and overnight cultures were grown in LB supplemented with carbenicillin (100 µg ml−1), chloramphenicol (38 µg ml−1) and 1% glucose at 37 °C. The overnight cultures were diluted 1:50 in fresh LB media supplemented with carbenicillin (100 µg ml−1) and chloramphenicol (38 µg ml−1). Upon reaching an OD600 of approximately 0.6, the media were supplemented with 1X metals (50 µM FeCl3, 20 µM CaCl2, 10 µM MnCl2, 10 µM ZnSO2, 2 µM CoCl2, 2 µM CuCl2, 2 µM NiCl2, 2 µM Na2MoO4, 2 µM Na2SeO3 and 2 µM H3BO3) and protein expression was induced with the addition of l-arabinose to a final concentration of 0.2%. Cells were cultured for an additional 4 h at 37 °C with shaking, and then harvested by centrifugation. The pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol and 1 mM TCEP), flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. Cells were lysed by three passes through an Emulsiflex-C3 cell disruptor (Avestin), then centrifuged at 15,000g for 30 min at 4 °C to pellet cell debris. The clarified lysate was subjected to ultracentrifugation at 37,000 rpm (182,460g) for 45 min at 4 °C in a Fiberlite F37L-8 ×100 Fixed-Angle Rotor (096-087056, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and the membrane fraction was solubilized in 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 25 mM DDM and 1 mM TCEP by rocking overnight at 4 °C. Insoluble debris was removed by ultracentrifugation at 37,000 rpm for 45 min at 4 °C. Solubilized membranes were then passed twice through a column containing Ni Sepharose Excel resin (Cytiva). Eluted proteins were concentrated using the Amicon Ultra-0.5 Centrifugal Filter Unit concentrator (MWCO 30 kDa, UFC503008) before separation on the Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 column (Cytiva) equilibrated in gel-filtration buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM DDM, 10% glycerol and 1 mM TCEP). LetA concentrations were quantified by gel densitometry using BSA standards.

Samples for ICP-MS analysis were prepared by adding 0.1 ml trace-metal-grade nitric acid to 1.9 ml of protein sample as provided. Samples were analysed using a Perkin Elmer NexION 350D ICP mass spectrometer. All liquid samples were infused into the nebulizer via peristaltic pump at 0.3 ml min−1. For full-scan elemental analysis, the instrument ‘TotalQuant’ method was used, using factory response factors. For quantitative analysis of zinc, calibrators were prepared by dilution of certified single-element standard (Perkin Elmer) with 5% nitric acid, and these were used to generate a standard response curve. Except for zinc, none of the 79 other elements tested, such as iron, nickel and cobalt, was enriched in the protein sample relative to the buffer control. These results suggest that the ZnR domains of LetA bind to zinc, although we note that the metal-binding properties of similar ZnR proteins can be sensitive to the experimental conditions49.

BPA crosslinking assays

OverExpress C43 (DE3) cells were transformed with plasmids to express LetAB (either WT or mutant forms derived from pBEL1284) or LetB (either WT or mutant forms derived from pBEL2782). The cells were co-transformed with pEVOL-pBpF (Addgene #31190) to encode a tRNA synthetase–tRNA pair for the in vivo incorporation of p-benzoyl-l-phenylalanine (BPA; F-2800.0005, Bachem) in E. coli proteins at the amber stop codon TAG82. Bacterial colonies were inoculated in LB supplemented with carbenicillin (100 μg ml−1) and chloramphenicol (38 μg ml−1) and grown overnight at 37 °C. The following day, bacteria were centrifuged and resuspended in 32P labelling medium (a low phosphate minimal media that we optimized starting from LS-5052 (ref. 83): 1 mM Na2HPO4, 1 mM KH2PO4, 50 mM NH4Cl, 5 mM Na2SO4, 2 mM MgSO4, 20 mM Na2-succinate, 0.2× trace metals and 0.2% glucose) supplemented with carbenicillin (100 μg ml−1) and chloramphenicol (38 μg ml−1) and inoculated 1:33 in 20 ml of the same medium. Bacteria were grown to OD600 = approximately 0.6–0.7 and a final concentration of 0.2% l-arabinose, 0.5 mM BPA and 500 μCi 32P orthophosphoric acid (NEX053010MC, PerkinElmer) were added and left to induce overnight at room temperature with shaking (220 rpm).

The following day, the cells were harvested by centrifugation (4,500g for 10 min) and resuspended in 1 ml of PBS (pH 7.4), and the ‘crosslinked’ samples underwent crosslinking by treatment with 365 nM UV in a Spectrolinker for 30 min. Both the crosslinked and uncrosslinked cells were centrifuged (6,000g for 2 min) and resuspended in 1 ml of lysozyme resuspension buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mg ml−1 lysozyme and 25 U ml−1 benzonase) and were incubated for 1 h at 4 °C. The cells then underwent eight cycles of freeze–thaw lysis by alternating between liquid nitrogen and a 37 °C heat block. The lysate was centrifuged at 20,000g for 15 min, and the pellets were resuspended in 250 µl of membrane resuspension buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol and 25 mM DDM) and shaken for 1 h. The sample volume was then increased to 1 ml with 10 mM imidazole wash buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl and 10 mM imidazole) and insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 20,000g for 15 min. Each supernatant was then mixed with 50 µl of Ni Sepharose Excel resin (Cytiva; 50% slurry) for 30 min. The beads were centrifuged at 500g for 1 min and the supernatant removed. The beads were then washed four times with 40 mM wash buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 40 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol and 0.5 mM DDM) and finally resuspended in 50 µl of elution buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 300 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol and 0.5 mM DDM). The samples were then mixed with a 5× SDS–PAGE loading buffer, and the beads were spun down at 12,000g for 2 min. Eluted protein was analysed by SDS–PAGE and stained using InstantBlue Protein Stain (ab119211, Abcam). Relative loading of the LetA or LetB monomer band on the gel was estimated integrating the density of the corresponding bands in the InstantBlue-stained gel in ImageJ84, and this was used to normalize the amount of protein loaded on a second gel, to enable more accurate comparisons between samples. The normalized gel was stained with InstantBlue, and the 32P signal was detected using a phosphor screen and scanned on a Typhoon scanner (Amersham). Three biological replicates of the experiment were performed, starting with an independent protein expression culture grown on a different day.

Disulfide-crosslinking assays

To perform these assays, we generated variants of our split-LetA construct. As one cysteine from each pair is within TMDN and the second Cys from each pair is within TMDC, we introduced these cysteine pairs into a variant of our split-LetA construct with non-essential cysteines removed (C124S, C266S and C343S; ΔCysSplitLetA), to facilitate the detection of the crosslink of interest. A crosslinking event is predicted to lead to covalent linkage between TMDN and TMDC, resulting in a dimer with a large molecular weight shift on SDS–PAGE relative to either domain alone. The metal-coordinating cysteines of the ZnR domains cannot be mutated without affecting LetA function, but are probably protected from maleimide crosslinkers by the bound zinc ion. Given that our DMS data suggest that Q180 and R380 can tolerate mutations to cysteines, we selected these residues to probe the alternative conformation. OverExpress C43 (DE3) cells (Lucigen) containing pBEL2802 or its mutants were grown overnight at 37 °C in LB medium supplemented with carbenicillin (100 µg ml−1) and 1% glucose. Overnight cultures were diluted 1:50 to 20 ml of fresh LB media containing carbenicillin (100 µg ml−1). Cells were grown to an OD600 of approximately 0.8, and protein expression was induced with the addition of l-arabinose to a final concentration of 0.2%. Cells were cultured for an additional 4 h at 37 °C, then harvested by centrifugation (4,500g for 10 min at 4 °C), and resuspended in 1.5 ml PBS pH 7.4. From this stock, 500 µl cell suspension was pipetted into two separate Eppendorf tubes, and either treated with 3% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; solvent used for dissolving crosslinkers) or with 1 mM BMOE (PI22323, Thermo Scientific Pierce). To cap unreacted cysteines, both the DMSO-treated and BMOE-treated samples were incubated with 2 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM; PI23030, Thermo Scientific Pierce) and incubated for 10 min at room temperature while rotating in the dark. To quench unreacted BMOE, the cells were incubated with 10 mM l-cysteine (168149, Sigma) for 10 min at room temperature while rotating. The cells were harvested by centrifugation (6,000g for 2 min), flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored −80 °C. To lyse the cells, the pellets were resuspended in 1 ml of lysozyme resuspension buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mg ml−1 lysozyme, 25 U ml−1 benzonase and 1 mM dithiothreitol) and incubated for 1 h at 4 °C. The cells then underwent eight cycles of freeze–thaw lysis by alternating between liquid nitrogen and a 37 °C heat block. The lysate was centrifuged at 20,000g for 15 min, resuspended in 250 µl of membrane resuspension buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol and 25 mM DDM and 1 mM dithiothreitol) and shaken for 1 h. Insoluble debris was removed by centrifugation at 20,000g for 15 min at 4 °C. For each sample, 20 µl of the supernatant was mixed with 20 µl 2X SDS–PAGE loading dye supplemented with fresh 50 mM dithiothreitol. The samples were heated to 50 °C for 15 min, and then 10 µl of the sample was loaded to an SDS–PAGE gel. The LetA bands were probed by western blotting using the monoclonal anti-LetA antibody (clone 72).

AlphaFold2 predictions

To identify the alternative conformations of LetA, we used AlphaFold2_multimer_version3 via Colabfold85. The sequence of LetA was retrieved from the MG1655 reference genome in the NCBI database. Program outputs yielded 5 ranked models, each with 32 samples or ‘seeds’, resulting in 160 predictions. Finding ambiguity in the co-evolutionary signal was achieved by reducing the depth of the input multiple sequence alignments (16:32), enabling ‘dropout’ and setting ‘recycling’, which is the number of times the structure is fed into the neural network, to 0 (refs. 51,85). Although many predictions showed ZnRN and ZnRC interacting with each other, 37 models showed different degrees of separation between the two ZnRs. In addition, five predictions exhibited severe clashes in ZnRC. These observations made it difficult to interpret the cytoplasmic region, which also includes the unstructured N-terminal and C-terminal regions that are not observed in our cryo-EM density, and we therefore focused on the TMD region. The RMSD heatmap was built as follows: first, each of the 161 PDBs (LetA cryo-EM structure and 160 models generated by AlphaFold) was aligned with all others PDBs using ‘align’ function from PyMol Molecular Graphics System (v3.0 Schrödinger, LLC), restricting the alignment to the carbon atoms and number of cycles to 0. Then, a matrix with the 161 PDBS in x and y was filled with the RMSD. Finally, the dendrogram was computed using the fastcluster Python package86 (using the Ward method and Euclidean metric). For each cluster, the representative model was selected as the one having the lowest average RMSD within that cluster.

System preparation for molecular dynamics

The LetAB complex used in the molecular dynamics simulations was constructed by integrating the cryo-EM-resolved structure with the AlphaFold2 multimer-predicted model using Chimera and Coot. Missing residues in the C-terminal region of LetA (residues 419–427) were reconstructed using AlphaFold2, whereas the N-terminal disordered region (residues 1–26) was excluded due to its low predicted local distance difference test score. Similarly, for LetB, the N-terminal absent residues (residues 1–13) were omitted for the same reason. We retained the TM helices and the first MCE ring of LetB (residues ≤ 160) to preserve the native environment surrounding LetA, whereas the remaining portions of LetB were excluded to minimize the system size. In addition, the two absent TM helices (residues 14–45) of LetB were modelled using AlphaFold2. The N termini of LetA and LetB were capped with an acetylated N terminus (ACE), whereas the C termini of LetA and LetB were capped with a standard C terminus (CTER) and a methylamidated C terminus (CT3), respectively. Protonation states of titratable residues were determined using PropKa3 (refs. 87,88). The orientation of the protein complex relative to the membrane was established using the Positioning of Proteins in Membranes (PPM) 3.0 web server89, and the resultant oriented protein complex was embedded into a native Gram-negative bacterial inner membrane using the Membrane Builder module in CHARMM-GUI90,91. Each membrane leaflet consisted of 1-palmitoyl-2-(cis-9,10-methylene-hexadecanoyl)-phosphatidylethanolamine (PMPE; 16:0/cy17:0), 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphatidylethanolamine (POPE; 16:0/18:1(9Z)), 1-pentadecanoyl-2-(cis-9,10-methylene-hexadecanoyl)-phosphatidylethanolamine (QMPE; 15:0/cy17:0), 1-oleoyl-2-(9Z-hexadecenoyl)-phosphatidylethanolamine (OYPE; 18:1(9Z)/16:1(9Z)), 1-palmitoyl-2-(cis-9,10-methylene-hexadecanoyl)-phosphatidylglycerol (PMPG; 16:0/cy17:0), 1-palmitoyl-2-(9Z-hexadecenoyl)-phosphatidylglycerol (PYPG; 16:0/16:1(9Z)) and 1,1′-palmitoyl-2,2′-(11Z-vacenoyl)-cardiolipin (PVCL2, 1′-[16:0/18:1(11Z)],3′-[16:0/18:1(11Z)]) in ratios of 46, 13, 12, 8, 10, 9 and 2, respectively. The cryo-EM-resolved lipid was elongated to PMPE (in simulations performed with Lipid 1), as it represents the most abundant phospholipid in the Gram-negative bacterial inner membrane. To assess the functional role of the cryo-EM-resolved lipid, we constructed systems both with and without Lipid 1. For each scenario, lipid positions within the membrane were randomly shuffled using the Membrane Mixer plugin92 in VMD to minimize any biases from initial lipid placement, resulting in three replicas for each condition, totaling six replicas overall. Finally, the resulting protein–membrane systems were solvated and neutralized with 0.15 M NaCl.

Molecular dynamics simulation protocols

All the molecular dynamics simulations were executed using the NAMD93 program. CHARMM36m94 and CHARMM36 (ref. 95) force fields were used for the proteins and lipids, respectively. The TIP3P model was used for water molecules96. Temperature was maintained at 310 K via a Langevin thermostat with a damping coefficient of γ = 1 ps−1, and pressure was held at 1 bar through the Nosé–Hoover piston97,98. The Particle-mesh Ewald99 method was used for calculating long-range electrostatic interactions within periodic boundary conditions at every time step. Non-bonded interactions were calculated with a cut-off of 12 Å, and a switching distance set at 10 Å. To accommodate volumetric changes in the system, a flexible cell was used, allowing independent fluctuations in three dimensions while preserving a constant x/y ratio for the membrane. The SHAKE100 and SETTLE101 algorithms were used to constrain bonds involving hydrogen atoms. For the initial equilibration and production runs, a 4-fs timestep was used, facilitated by hydrogen mass repartition102,103 to accelerate the simulations. A 2-fs timestep was applied without hydrogen mass repartition for non-equilibrium simulations involving collective variables (Colvars)104, as well as any subsequent equilibrium simulations.

To equilibrate the membrane–protein systems, each system underwent an initial 10,000 steps of energy minimization using the steepest descent algorithm, followed by equilibrations with gradually reduced harmonic restraints105. Initially, only the phospholipid tails were allowed to move without any constraints for 1 ns in an NVT ensemble (constant number of particles, volume and temperature), followed by a 10-ns phase where all components excluding the protein were unrestrained in an NPT ensemble (constant number of particles, pressure and temperature). Subsequently an additional 10-ns simulation was performed to allow all components except the protein backbone to move freely under NPT. A force constant of 10 kcal mol Å−2 was applied to the restrained atoms. Finally, all restraints were removed, and each system was subjected to a 2-µs production run. In each of the six replicas (three with Lipid 1 present at the start and three without), a lipid moved spontaneously upwards into the Lipid 2 site in the central cleft. The identity of Lipid 2 varied, and was PMPE in four replicas, PYPG in one replica and cardiolipin in one replica. See Supplementary Table 2 for the reliability and reproducibility checklist for molecular dynamics simulations.

Steered molecular dynamics simulations

To elucidate the potential mechanisms and pathways for phospholipid transport and evaluate the feasibility of accommodating a phospholipid within the periplasmic pocket in TMDC, a series of SMD simulations were conducted. These simulations used Colvars to direct the upwards movement of Lipid 2 from the central cleft, starting from the poses identified in previous molecular dynamics simulations. Forces were applied to the centre of mass (COM) of three specific regions of Lipid 2: the head group, the terminal six carbons of the tail closest to the bottom of the periplasmic pocket, and the terminal six carbons of both tails. Each pulling scenario used a stepwise protocol with the distanceZ Colvars to avoid unintended pathways, ensuring that the pulled atom group traversed the periplasmic pocket in TMDC. The lipid was initially steered towards the bottom of the periplasmic pocket in TMDC, followed by movement towards the middle of the pocket, and ultimately to the top of the pocket. Initial configurations for these SMD simulations were derived from the final frame of the 2-µs production run of replica 2 for the system with Lipid 1 and replica 3 for the system without Lipid 1, as they represented the lipids with the most elevated positions for each condition. This results in six distinct SMD setups (two initial configurations × three pulling scenarios). To ensure optimal interactions between the pulled lipid and its surrounding environment, the pulling velocity was set to 0.2 Å ns−1 with a force constant of 10.0 kcal mol Å−2. The duration of each simulation is provided in Supplementary Table 3. Throughout the SMD simulations, the centerToReference and rotateToReference options in NAMD were enabled to align LetA with its initial conformation before calculating distances and forces at each timestep, which avoided the effects of protein translation and rotation on the applied force. In addition, the z-centre of LetA was harmonically restrained using the harmonicWalls function in Colvars with a force constant of 10.0 kcal mol Å−2 and the lower and upper wall thresholds set at −2 Å and 2 Å, respectively. This restraint prevented the global upwards movement of LetA induced by the applied forces on Lipid 2, which could otherwise distort the local membrane structure.

Following the completion of SMD simulations, the systems underwent an additional 10-ns equilibration phase, during which the protein backbone and the heavy atoms of the pulled lipid were harmonically restrained with a force constant of 10 kcal mol Å−2. All restraints were subsequently removed, and a 300-ns production run was conducted for each system.

Water bridge network analysis

To investigate the potential role of polar residues (D181, K178, S321, K328, S364, D367 and T402) in TMDc in a proton shuttle pathway, hydrogen bonds were analysed on a frame-by-frame basis across simulation replicas. This included hydrogen bonds formed directly between the residues, between each residue and adjacent water molecules, and among the water molecules themselves. Hydrogen bonds were defined using the geometric criteria: a donor–hydrogen distance cut-off of 1.2 Å, a donor–acceptor distance cut-off of 3.0 Å, and a minimum donor–hydrogen–acceptor angle of 120°, ensuring the inclusion of only well-structured hydrogen bonds.

The occupancy of hydrogen bonds is defined as the fraction of total simulation frames in which a given hydrogen bond is observed. Water bridges were classified by their order: direct residue–residue hydrogen bonds with no intervening water molecules were designated as zero-water (0-W) bridges, whereas those involving one, two or three intervening water molecules (1-W, 2-W and 3-W bridges) were identified by systematically linking residue-to-water and water-to-water hydrogen bonds, thereby constructing higher-order networks. To visually represent the water bridge networks with the highest occupancy, principal component analysis was applied to project the spatial arrangement of residues into two dimensions. Each residue was depicted as a node, with edges connecting the nodes to represent the highest-occupancy water bridge between the residues, and the thickness of the edges indicating the relative occupancy of the corresponding water bridge.

Sample preparation for LC–MS lipidomics

Three replicates for each protein were analysed, with each replicate containing a purified protein in detergent, a detergent buffer negative control and an isolated E. coli membrane positive control. The lipids from each sample were extracted via Folch extraction. In brief, varying amounts of sample, chloroform, methanol, EquiSPLASH LIPIDOMIX (Avanti Polar Lipids) internal standards and water were combined as described in Supplementary Table 4. The bottom layer was extracted, dried using N2 gas and resuspended in 100 µl of liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) grade methanol. Each sample was analysed using data-dependent acquisition (DDA) LC–MS/MS. After DDA data collection, 30 µl of each sample was diluted with 50 µl LC–MS-grade methanol to ensure sufficient volume for triplicate MS1-only injections for quantitation. Sample identities were blinded for data collection and analysis, and unblinded for statistical analysis.

Data-dependent LC–MS/MS lipidomics

Lipids were separated before MS analysis using a 21-min trap-and-elute method as previously described106,107. A Waters XBridge Direct Connect HP C8 column (10 µm, 2.1 × 30 mm) was used as the trap column, and a Waters Premier Acquity UPLC CSH C18 column (1.7 µm, 2.1 × 100 mm) was used for analytical separations. Gradients for the C8 (trap) and C18 (analytical) columns were controlled by the α-pump and β-pump, respectively, and are provided in Supplementary Table 4. The column selection valve position was changed at 0.50 min, allowing the β-pump to flow through both the C8 and C18 columns. At 17.50 min, the valve reverted to the initial position to allow for washing and re-equilibration of the C8 and C18 columns by the α-pump and β-pump, respectively. A 10 µl sample injection volume was used, and the column compartment was held at 60 °C. Samples were ionized via electrospray ionization in negative mode and introduced into a Synapt XS mass spectrometer operated in sensitivity mode. The capillary and sampling cone voltages were set to 2.45 kV and 49 V, respectively. The source offset was 80 V, the source temperature was 120 °C and the desolvation temperature was 250 °C. A top 5 DDA method was applied, with an accumulated total ion chromatogram threshold of 100,000 and a maximum acquisition time of 0.25 s. MS1 and MS2 spectra were collected from 50 to 2,000 Th in continuum mode at a resolution of 10,000 with a scan speed of 0.1 s, and fragmentation was performed using collision-induced dissociation with a collision energy ramp from 20 to 40 V in the trap cell. Dynamic exclusion was used with an exclusion time of 15 s and an exclusion width of 0.5 Da. A fixed exclusion range of 50–450 Th was used to minimize selection of non-lipid precursors. Blank injections of isopropyl alcohol were performed every three samples using the same instrumental methods.

Collection of MS1-only LC–MS lipidomics data

After using DDA methods to identify the lipids, we used MS1-only scans to perform quantitation with accurate mass and retention time alignment, as described previously106,107. Of each diluted sample, 10 µl was loaded and separated as described above. MS1 scan parameters were identical to DDA MS1 scans. Triplicate injections of each sample were performed in a randomized order. Isopropyl alcohol injections (10 µl) were performed after each sample run to mitigate potential carryover between samples.

Lipid library construction with DDA lipidomic data

All DDA files were centroided using MSConvert, and mass calibration was performed using an in-house Python script using the known masses and retention times of the EquiSPLASH lipids. Lipid identification based on the calibrated DDA data files was performed using MS-DIAL (v5.3)108. A minimum peak height of 1,000 and mass slice width of 0.1 Da were used for peak detection. Only CL, PE and PG lipids were searched, as these are the most prevalent lipids in E. coli. MS1 and MS2 accurate mass tolerances of 0.025 Da were used, and both [M-H]− and [M + CH3COO−]− adducts were allowed. For alignment, a retention time tolerance of 0.5 min and mass tolerance of 0.015 Da were used. A set of high-quality lipid identifications was then manually checked to produce a lipid library to be used for MS1-based lipid quantification.

Processing of MS1-only lipidomics data

MS1-only files were centroided and calibrated in the same way as DDA files, with the addition of retention time calibration using the known retention times of EquiSPLASH-spiked lipids. Calibrated MS1 files were loaded into Skyline (v23.1.0) and searched against the DDA-constructed lipid library109. An ion match tolerance of 0.05 Th and mass accuracy of 10 ppm were used. To ensure accurate quantification, each extracted-ion-chromatogram integration was manually checked and adjusted as necessary. Raw peak areas were then standardized to sample volume and total identified lipid area. Finally, we compared the enrichment of specific lipid classes between the isolated protein samples and the starting membranes. First, within each individual sample, the total intensity of each lipid class (CL, PE and PG) was calculated by summing the standardized areas of each individual lipid in each class. The average total peak area for each class was then calculated using the summed areas from each replicate. To compare the lipid composition in the protein samples relative to the E. coli membranes, the average fold change was then calculated for each class between the protein and membrane samples. Standard deviations were propagated through the averaging, and a 95% confidence interval for the fold change was calculated. A two-sample Student’s t-test comparing the means of each lipid class area between the protein and membrane samples was performed, and P values were corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg method. A significance level of 0.05 was used to determine statistically significant differences.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.